What is the Stalinist Empire style in architecture?

During Stalin's rule, early Soviet experiments in architecture - in Constructivist and Art Deco styles - were replaced by a return to Neoclassicism. After World War II, in the second half of the 1940s, the style evolved into the hyper-monumentalism that’s today known as the "Stalinist Empire" style.

The country that had defeated Nazism now turned to Classical models and began to mythologize both the past and present, and not only in architecture but also in interior design, furniture and ornamentation. The new style was designed to demonstrate the greatness and power of the Soviet state.

In Soviet times (and particularly under Stalin), this style was described simply as "Soviet architecture". Only later did people begin to call it "Stalinist architecture"; but the term "Stalinist Empire" circulated unofficially among specialists for a long time. Art historian Selim Khan-Magomedov was one of the first scholars to use and propose this term.

The Stalinist Empire style incorporated elements of many architectural styles. It had features of the Renaissance and Classicism, with its endless columns, porticos, sculptures and perfect symmetry, as well as the swirls and excesses of Rococo and Baroque. In addition, there are the numerous bronze details of the French Empire style. The influence of American skyscrapers in Art Deco style is also evident. The Soviet state emblem and the five-pointed star were an integral decorative element.

The initial inspirations for this style have their origins in the 1930s and the first, albeit unrealized, project was the Palace of Soviets that was planned for the site of the demolished Cathedral of Christ the Saviour. Many prominent architects took part in the competition, but in the end the project submitted by Boris Iofan was chosen and approved.

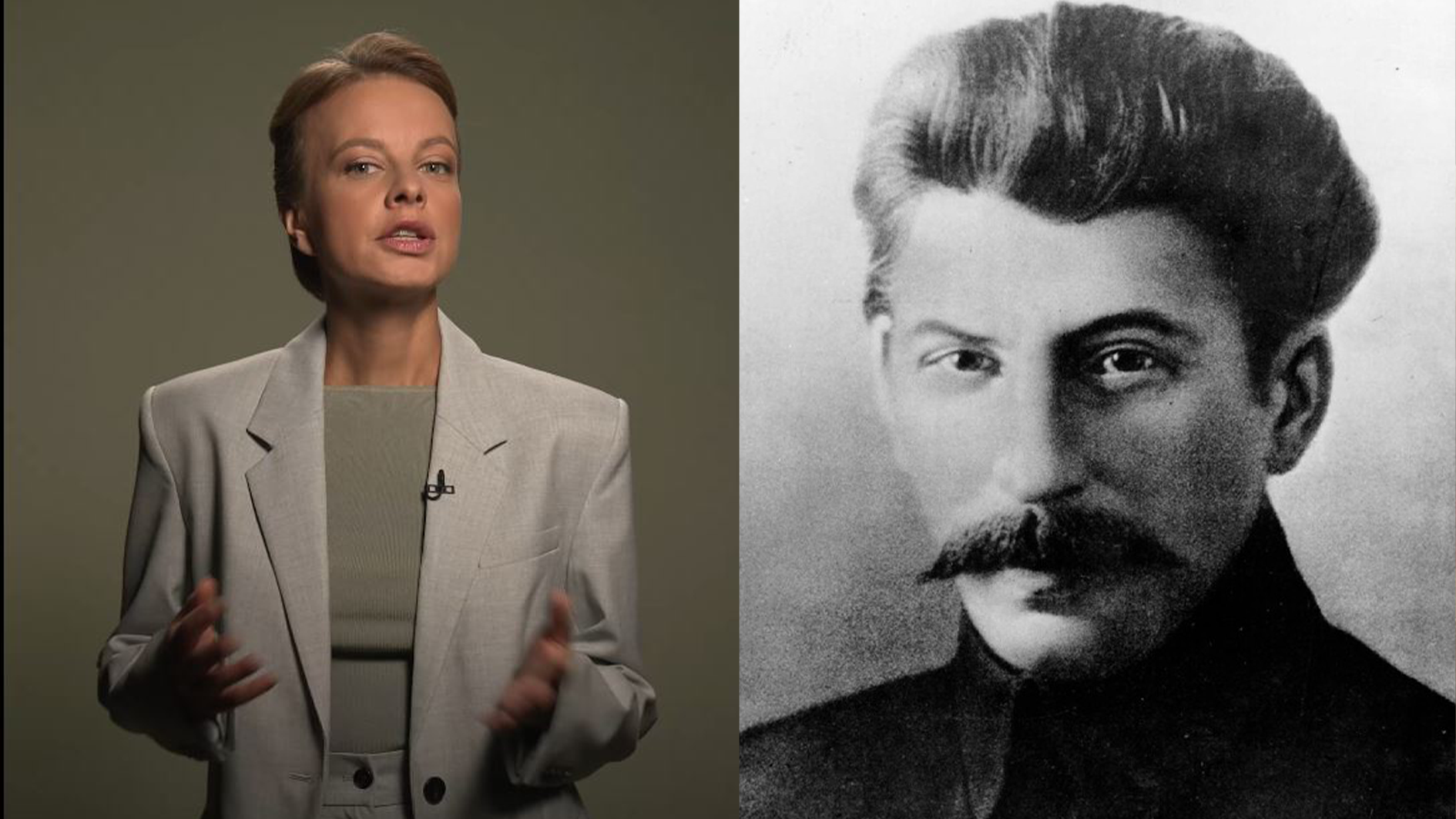

It’s widely believed that Joseph Stalin personally initiated and ideologically inspired many of the buildings, and that he approved all the projects. Among the prominent architects who had a keen sense of what was required from the Soviet leader and his new buildings were Lev Rudnev, Arkady Mordvinov, Modest Shepilevsky, Vladimir Shchuko, and many, many others.

Central Pavillion at VDNKh

Central Pavillion at VDNKh

The entire site for the Exhibition of Achievements of National Economy (VDNKh) was built in this grandiose style. Each Soviet republic had its own pavilion that combined ethnic motifs with Stalinist architecture. Colossal fountains were also put up here. For instance, the Friendship of the Peoples Fountain consists of statues covered in gold leaf personifying the Soviet republics - seen as a reminder of the imperial residence in Peterhof.

Friendship of the People's' Fountain at VDNKh

Friendship of the People's' Fountain at VDNKh

The entrance to Moscow's Gorky Park was also built in this style.

Main entrance to Gorky Park

Main entrance to Gorky Park

The North River Terminal building is also a monument to the Stalinist Empire style. It had a particularly emblematic significance as it was built for the opening of the Moscow-Volga Canal, one of the main Stalinist projects.

North River Terminal in Moscow

North River Terminal in Moscow

Moscow's "Seven Sisters" became the main symbol of this style; the plans for each of the skyscrapers were personally approved by Stalin.

Skyscraper on Kotelnicheskaya Embankment

Skyscraper on Kotelnicheskaya Embankment

The monumental skyscrapers crowned with spires became genuine testimonies to the Stalin era. No expense was spared on their construction.

Main building of Moscow University

Main building of Moscow University

Soviet architects widely used ornamental elements from Western Europe's Empire style, which had its roots in Napoleonic France. In the USSR this style was stripped of superfluous baroque mannerisms; gold, stucco work, wood carving and bas-reliefs could be seen on both the outside and inside of these Stalin-era buildings.

Interior of one of "Stalin's skyscrapers "- the Ukraina Hotel

Interior of one of "Stalin's skyscrapers "- the Ukraina Hotel

Apart from the skyscrapers, residential buildings - the so-called "stalinki" - were built in the whole of central Moscow as abodes for the Soviet nomenklatura. Their facades were also adorned with columns, projecting windows with balconies and ornate cornices. This residential building was erected in the second half of the 1940s for employees of the Soviet Ministry of State Security, which was recognized as a Stalinist Empire masterpiece. The architect, Yevgeny Rybitsky, was even awarded the Stalin Prize for this building.

Apartment building for employees of the Soviet Ministry of State Security (Moscow, Zemlyanoy Val, 46)

Apartment building for employees of the Soviet Ministry of State Security (Moscow, Zemlyanoy Val, 46)

Two semicircular buildings on Gagarina Square - their construction completed by 1950 - form a ceremonial entrance to the center of Moscow.

Gagarina Square

Gagarina Square

Many stations of the Moscow Metro, which today are described as underground palaces, were built in the Stalnist style. Their key distinguishing features are columns, bas-reliefs, a profusion of mosaics, and also vast and extravagant light fittings.

Komsomolskaya Metro Station

Komsomolskaya Metro Station

Although the capital was of course the principal showcase for this style, the Stalinist Empire style spread beyond Moscow. "Stalinki"-type residential buildings were built in numerous cities and regional centers.

A 1953 "stalinki" style building in Kazan

A 1953 "stalinki" style building in Kazan

Stalingrad is the city of military glory where, during World War II, Soviet troops scored one of their most significant victories. The Square of the Fallen Fighters in the city center was completely built in the Stalinist Empire style, along with all the buildings nearby – a hotel, post office, theater and railway terminal building.

The Square of the Fallen Fighters in Volgograd (former Stalingrad)

The Square of the Fallen Fighters in Volgograd (former Stalingrad)

Stalin also chose this style when designing buildings for his own personal use. Thus, the interiors of his private offices and dachas have all the distinguishing marks of grandiosity, albeit in a more restrained manner: plush curtains with decorative fringes, wood parquetry, large light fixtures, and much more.

Stalin's dacha in Sochi

Stalin's dacha in Sochi

Stalin's dacha in Sochi

Stalin's dacha in Sochi

The triumphalist Stalinist Empire style persisted until the mid-1950s, but then suddenly disappeared after the death of Stalin. A decree was promulgated in 1955 "On the elimination of excesses in planning and construction".

Architectural excesses in the decorative plans of the Stalinist era were criticized. A new Party line was proclaimed - one of simplicity and severity of form. This is how monumental Classicism in architecture was replaced by standardized construction with a minimal amount of decoration. In the mid-1950s the "stalinki" made way for the first “khrushchevki".