5 reasons to watch Russia’s newest adaptation of ‘The Master and Margarita’

The story about the Devil’s misadventures in Stalin-era Moscow was difficult to publish for a long time; the same fate befell screen adaptations. Many tried their hand at adapting the “cursed” novel, including Baz Luhrman and Elem Klimov (the director behind the legendary 1985 anti-war movie ‘Come and See’). However, many of these versions never saw the light of day. The current adaptation is the sixth in line and, according to both audiences and critics, it hits the mark like no other. Let’s look at the reasons in more detail.

1. Everyone talks about the Bulgakov novel as being cursed - and the latest production is no different

The press loves to speculate about the alleged curse of ‘The Master and Margarita’ and all attempts at adapting it to the screen. There was the time when Oleg Basilishvili, who played Woland in the 2005 Russian TV series, briefly lost his voice during filming. Journalists also noted the eerie string of actor deaths that followed the show’s premiere - 18 of them, in the space of just a few years! Superstitions aside, it’s still true that every attempt at transferring Bulgakov’s novel onto the screen was plagued with major hurdles. And this latest motion picture was not an exception.

Nikolay Lebedev (‘Legend No. 17’) was first in line to direct the current adaptation and is also the man behind the original screenplay. However, there was a mix-up with the rights, with different descendants of Bulgakov having sold them to different companies: it turned out that, while the current Russian movie was in production, Hollywood was busy making its own adaptation with Australian director Baz Luhrman (‘The Great Gatsby’, 2013) at the helm.

Once the legal stuff was finally sorted out, the Covid pandemic struck, halting production. Lebedev refocused his attention on his war drama ‘Nurnberg’, while ‘The Master and Margarita’ was passed to a different production company, which overhauled the existing script entirely.

2. Breakout director Michael Lokshin was involved, whose ‘Silver Skates’ became a Netflix hit

American-born Michael Lokshin first rose to prominence as an ad and music video director. Among other things, there’s 2014’s ad for ‘Sibirskaya Korona’ beer, starring David Duchovny, known for his iconic role as Mulder from the cult show ‘The X-Files’ (1993-2018) - who, by the way, has Russian roots: In the short clip, which went viral in Russia, Duchovny fantasises about what it would have been like had he been born in Russia.

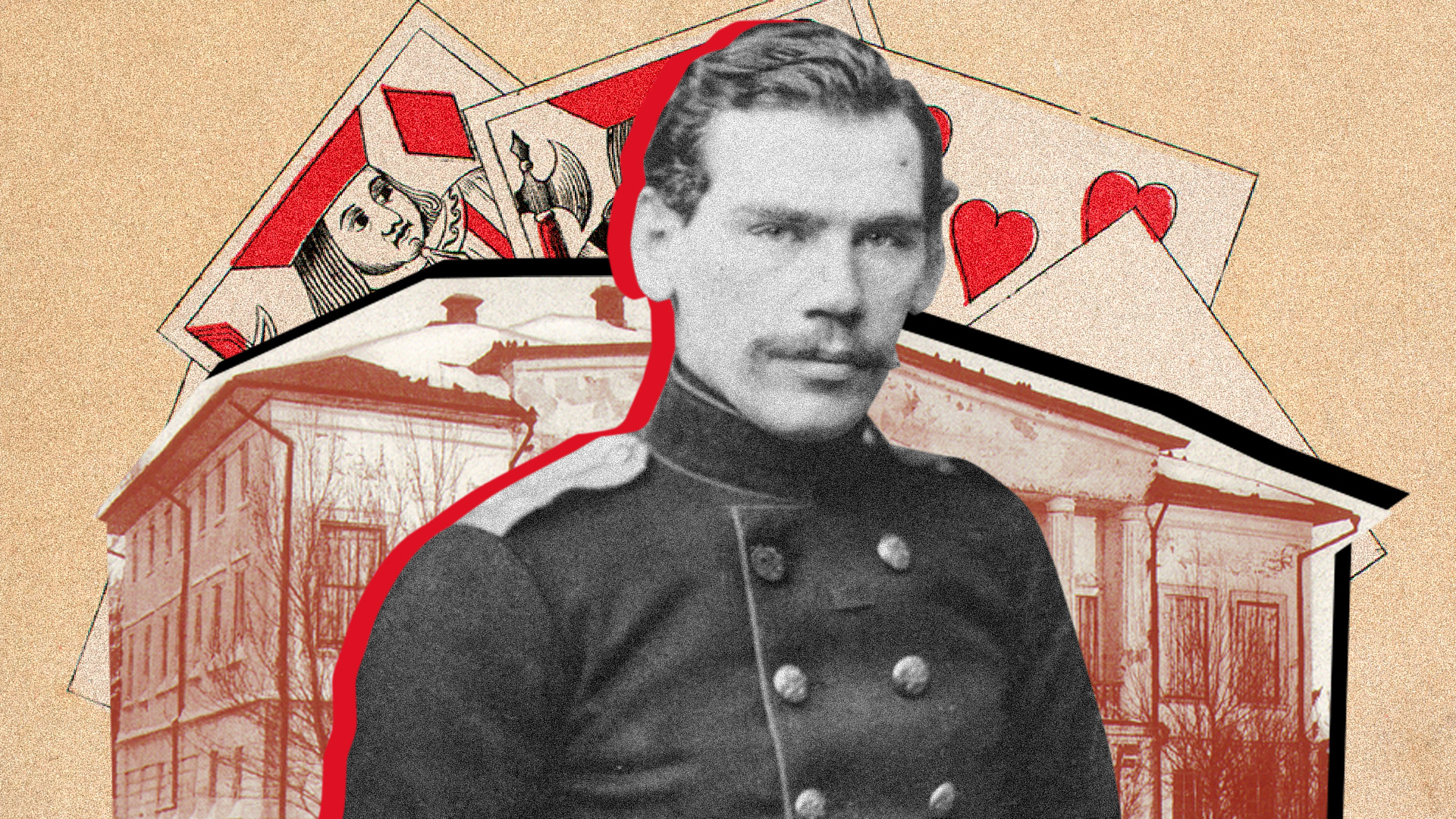

Lokshin’s big-screen debut came with ‘Silver Skates’ (2020) - a Christmas tale about a small gang of ice-skating thieves in tsarist St. Petersburg, which became the first in Russia to become a Netflix Original: previously, only the Russian TV shows ‘To the Lake’ and ‘Better Than Us’ made the lineup. The movie, meanwhile, also made it into Netflix’s Top 5 upon release.

‘The Master and Margarita’ is only Lokshin’s second stab at directing a full-fledged motion picture. The screenplay was written by ‘Silver Skates’ author Roman Kantor, who previously worked on ‘To the Lake’.

3. The movie uses non-linear storytelling, preferred by famed director Christopher Nolan

Nikolay Lebedev’s cancelled version of the adaptation was going to keep the novel’s original narrative structure, while Lokshin and Kantor opted for a more postmodern approach, similar to Christopher Nolan’s ‘Inception’ (2010) and ‘The Prestige’ (2006).

The story arc has been retained from the novel: There’s the love story between the Master and Margarita, as well as Woland’s interference and ‘the Master’s gospel’ – a play on the tale of Christ and Pontius Pilates, the Roman prosecutor who was tasked with crucifying him. However, the script was made more complex and now resembles a matryoshka (Russian nesting doll), wherein one story exists inside another and so on – with each progressing simultaneously.

The choice to go this route isn’t some gimmick, either, but an attempt to explain Bulgakov’s own method. The result is that the current ‘Master’ has become a closer approximation of Bulgakov’s original style than that witnessed in the actual novel. Evgeny Tsyganov – currently, one of the most sought-after Russian actors – plays the author himself. We get to witness actual facts from Bulgakov’s biography – the fight against censorship, repressions and betrayal at the hands of friends – play out on screen in the form of phantasmagorical story lines.

4. German actor August Diehl plays Woland, while Pilate is portrayed by Danish actor Claes Bang

The casting is fantastic all around. In the past, Woland used to be portrayed as a wise, evil, old man, while Diehl’s portrayal is much more of a witty, fun and mischievous prankster. He really enjoys executing his judgment on Muscovites. Pontius Pilate, meanwhile, is played by Danish actor Claes Bang, best known for his role in BBC’s ‘Dracula’ TV show. The Russian actors are also well cast – especially, Tsyganov as the Master and Yuliya Snigir as his beloved Margarita (the two are married in real life). Snigir will be recognized by some from her roles in ‘A Good Day to Die Hard’ (2013) and ‘The New Pope’ (2020).

5. The movie’s visuals combine Gatsby-style art-deco with Stalinist steampunk

The movie is set in the minds of its protagonists, so, reproducing the actual Moscow of the 1930s wasn’t the visual artists’ prime concern. Stalin’s pompous Empire style is magnified to grotesque levels – there are the constant ‘vysotki’ high-rises, reminiscent of Mesopotamian ziggurats. With CGI, the creators also committed to screen the unrealized projects – among them, the grandiose Palace of the Soviets, with its 100-meter statue of Vladimir Lenin, as well as the traditional futuristic-looking zeppelins in the skies above.

The Muscovites in the movie certainly know how to party. The jazz shows in an exclusive writers’ club resemble something out of Baz Luhrman’s ‘The Great Gatsby’; a black magic seance at the theater looks more like a Paris fashion show; while Woland’s entourage is colorfully portrayed in a very commedia dell’arte sort of way. Finally, Satan’s great ball appears as a sort of pre-Christian – even pre-antique – affair: the wardrobe and interior design seem to hark back to the era of Ancient Egypt and Babylon.