Vasily Surikov’s ‘Boyarina Morozova’ painting EXPLAINED

This giant canvas is 3 x 5.8 meters in size. It was first shown to the public at an exhibition of peredvizhniki realist artists in 1887. First impressions were controversial and some critics even compared the canvas with a mottled Persian carpet. The work was bought for Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery and still is on display on its walls being one of the brightest gems of the collection.

Who is Boyarina Morozova?

Her name was Feodisiya Morozova and she was a noblewoman and had the highest origins. She was daughter of a queen’s butler, Prokofy Sokovnin. And when she was 17, she married 54-year-old nobleman, statesman and military leader Gleb Morozov, one of the richest men in Russia. He had a boyar title and she became a boyarina, a wife of a boyar (Read more about who the boyars were here).

After the death of her husband, she lived in a luxurious estate with about 300 servants and was close to Tsar Alexey Mikhaylovich’s court.

Why was she arrested?

In the 1650s, Patriarch Nikon initiated the church reforms which caused the Schism of the Russian Church. The tsar supported the changes, but some of the noblemen didn’t, with Morozova being one of them.

She became a so-called Old Believer, a protestant to the official Church. And she became close to Archpriest Avvakum, one of the movement’s ideologists, who was later executed by being burned alive. Tsar Alexey wanted to punish Morozova for not being loyal, but she had high-ranked intercessors and even the tsar’s wife asked not to sanction Morozova.

However, the deeply believing boyarina was in opposition and stopped visiting the court’s events. The tsar became angry when she refused to visit his second wedding, so he ordered her arrest.

Together with her sister, the boyarina was shackled (which was unthinkable to imagine for a noble woman) and transferred to a monastery in Borovsk outside Moscow. Because of her noble friends, including those from the royal family, she wasn’t burned alive, but she was made to die from starvation.

What’s so special about the painting?

One can literally spend hours in front of this painting exploring details, faces and dress. And near the picture in the gallery are several of Surikov’s sketches for it.

The boyarina is pictured in shackles, sitting on a cart taking her into exile. One of the first things that you can notice on the painting is the expressive face of the boyarina. She seems to be in despair, she looks exhausted and pale, but determined and almost fanatical. This was an unusual depiction of her image that earlier appeared in some paintings as a holy blessed Old Believer martyr, not a warrior. And Surikov’s earlier sketch shows another emotion on her face…

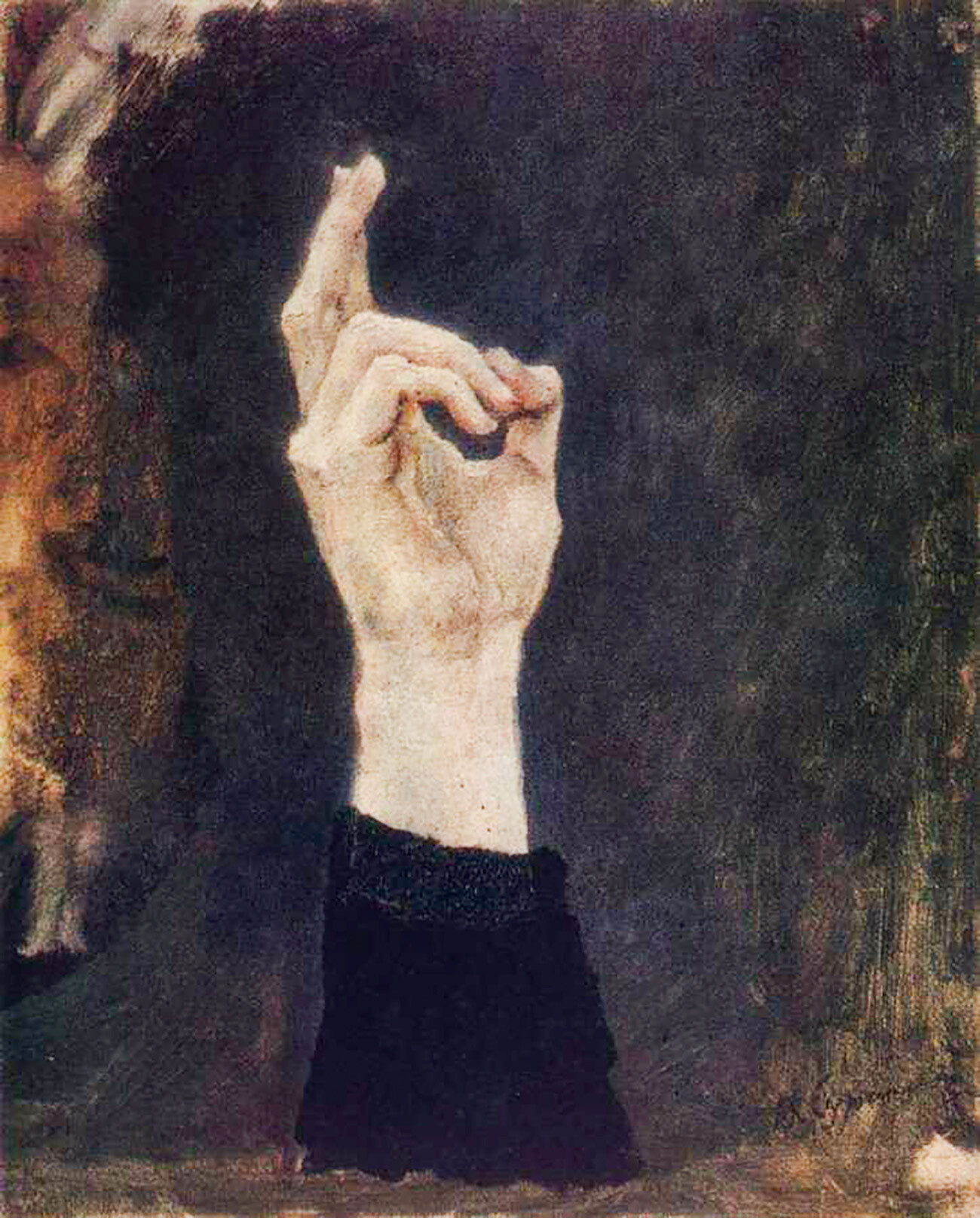

A very important part is Morozova’s right hand raised above her head. She is showing an Old Believers’ cross sign with two fingers. This is one of the symbols of the movement, because the reform made people cross with three fingers.

The supporters of the ‘bicuspid baptism’ insisted that Jesus Christ was crucified in his dual nature of God and God’s son, not in the holy Trinity (the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit) concept that appeared later.

An important part of the painting and actually the reason for its huge size is actually the people around. First of all, it’s a great way to look at the traditional Russian 17th century dress. But also, just take a look at how many emotions are pictured on the faces. There are people making fun of the fanatical woman. But lots of people are sad and baffled, even terrified. It seems that they are compassionate Morozova and maybe even agree with her conception of the faith, but are not so brave to express it, being afraid of persecutions.

But one man who doesn’t seem afraid is a beggar sitting cross-footed in rags and barefoot in the snow. He also demonstrates a two-finger sign. These kinds of men used to be called ‘holy fools’ in Russia. They could speak out the truth freely and were considered to be blessed by God.

Why did Surikov paint it?

The painting made a splash and attracted a big interest in 1887 when it was first exhibited. Сontemporaries left controversial feedback on these historical paintings, but they all agreed on one thing: this is an incredibly talented realistic reflection of the “Old” Russia of pre-Peter the Great times in its authenticity.

How could an artist in the late 19th century be so accurate? The thing is that Vasily Surikov grew up in Siberia, where lots of Old Believers lived. They were still in the semi-legal position and they were descendants of those who were exiled in the 17th century, because of their understanding of faith. And that’s where he got acquainted with the story of Morozova, who Old Believers considered their saint martyr.

Surikov was deeply sympathetic to these people, which most of Moscow and Petersburg 19th century secular society considered medieval fanatics and that’s why he showed that much spectrum of emotions on the paintings.

At the same time, the success of the painting was the rising interest in the “Russian Style” and all things authentically Russian. After two centuries of the comprehensive influence of European art in Russia, in the late 19th century, artists referred to the national realities, started painting peasants, ordinary people’s lives and everyday scenes from medieval Russia.