10 works by Erik Bulatov that you need to know (PICS)

1. “The Cut”, 1965-1966

Bulatov took up art early in life, starting to draw when he was just six years old. At that time, he tried to create his own illustrations for Ruslan and Lyudmila by Alexander Pushkin. When his father took a look at his drawings, he quickly realized that the young Erik was destined to become an artist. Subsequently, there was no difficulty in choosing his education and future profession. As a young man, Bulatov studied under leading Moscow artists Vladimir Favorsky and Robert Falk, both of whom in many ways influenced his style. One of the artist’s early works, “The Cut”, at first seems like an optical illusion; but when you take a close look, you’ll notice the painting’s depth and the light coming from inside of it.

2. “Horizon”, 1971-1972

Life itself gave Bulatov plenty of subject matter for creative inspiration: Once in Crimea he fell ill and went to the local clinic for treatment. During that time, the artist tried to catch a glimpse of the sea, but a red beam was in the way. No matter how hard he tried, he couldn’t overcome his obstructed view. At that moment the idea came to him to create an artwork that would utilize a feature with a natural barrier covering the painting’s most important subject matter. That’s how “Horizon” appeared – an idyllic seascape that’s ruined by a red carpet obstructing the horizon.

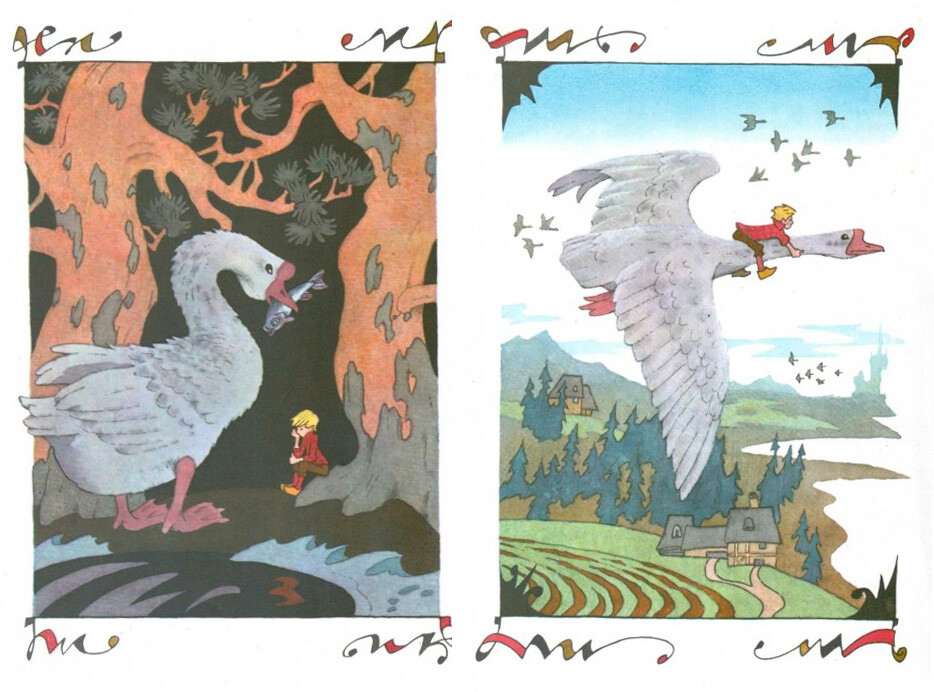

3. “The Wonderful Adventures of Nils”, 1978

Along with other now-famous artists – such as Ilya Kabakov and Oleg Vasiliev – as a young man Bulatov originally worked as a book illustrator. He made illustrations for fairy tales by Charles Perrault and stories by Boris Zakhoder, Sergei Mikhalkov and Genrikh Sapgir, Selma Lagerlöf, and the Brothers Grimm. This manner of earning a living – half a year spent working for the publishing house, the other half for himself – allowed Bulatov to have plenty of time for his own artistic exploration.

4. “Glory to the CPSU”, 1975

In the 1970s, the artist began merging landscapes and poster captions. One of the most vivid examples was the painting, “Glory to the CPSU”. Bulatov still considers it one of his major works of the Soviet period. Giant red letters literally ‘battle’ the idyllic landscape, blocking out the world of freedom. In 2008, this work was sold for 1.08 million British pounds sterling at Philips Auctions. In 2003, the artist made an author’s official reproduction that is now in the collection of the Centre Pompidou in Paris.

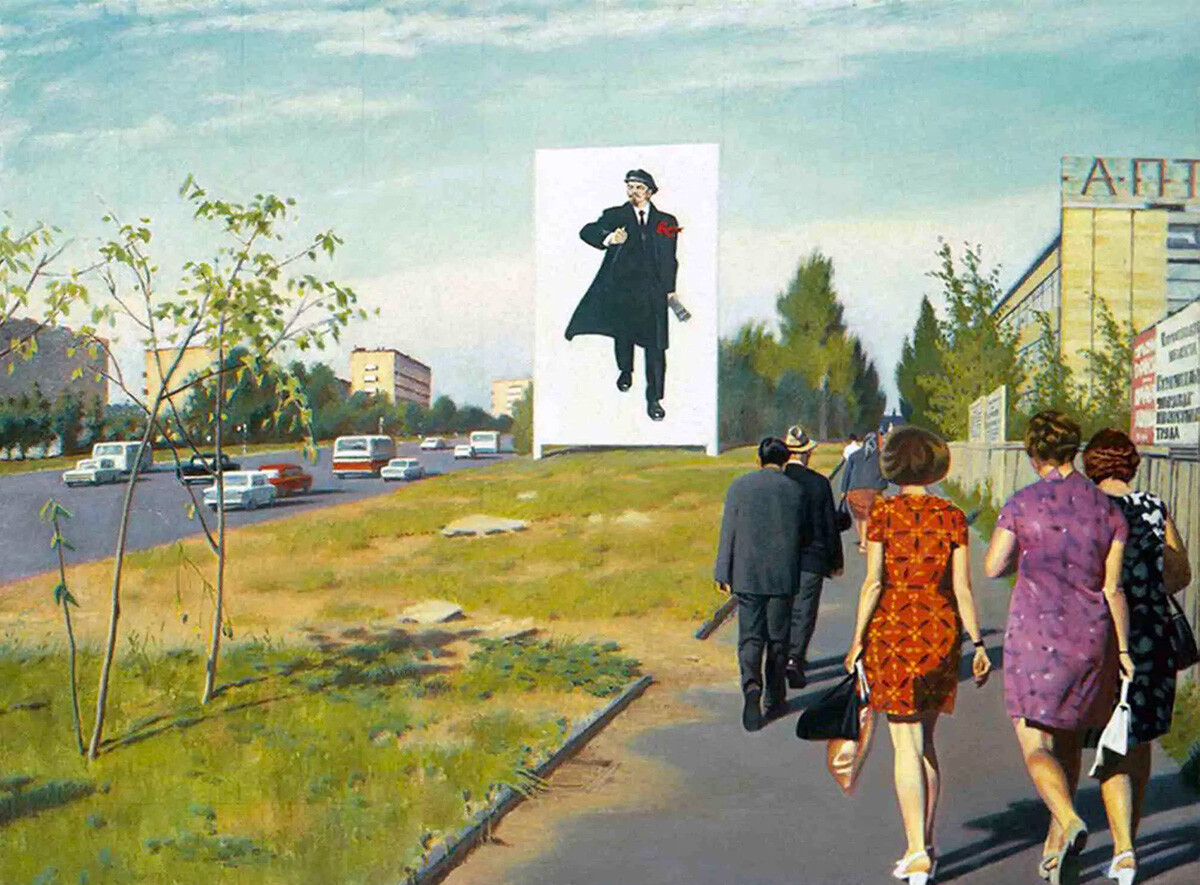

5. “Krasikov Street”, 1977

It was difficult to exhibit unofficial art in the USSR; for example, Bulatov’s exhibition at the Kurchatov Institute was on display for barely an hour before it was shut down. Overseas, however, people were more interested in the artist’s works and requested them for exhibitions. The Soviet Ministry of Culture deemed the incomprehensible art as not possessing any artistic value, and so the paintings were given permission to travel to private galleries overseas for exhibitions. At the same time, the artist continued to experiment: ‘obstacles’ appeared in his hyper-realistic landscapes, which obstructed movement and views. For example, in the “Krasikov Street” painting, a giant poster with Lenin stands in the middle of the road: it’s unclear if the road exists beyond it or not.

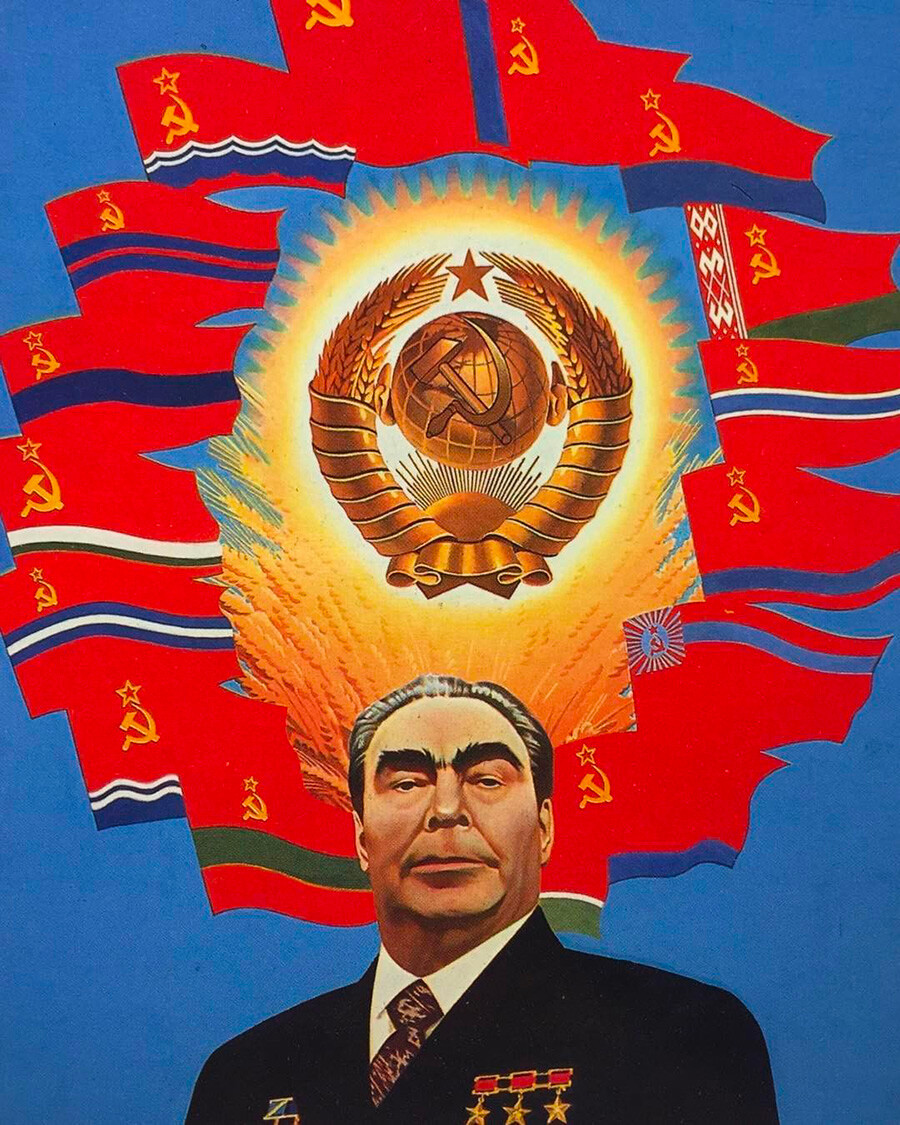

6. “Brezhnev. The Soviet Space”, 1977

The ironic perspective of the artist has often been taken at face value. This was the case, for example, with the painting “The Soviet Space”. And still, the portrait of Secretary General Brezhnev, surrounded by a halo of the flags of the Soviet Republics, was banned. Bulatov himself said that with this painting he tried to draw attention to the abnormality of social conventions that the majority of people considered to be the norm.

7. “Melting Clouds”, 1982-1987

References to other artists are common in Bulatov’s works. For example, “The Door is Open” is a homage to 17th century painter Diego Velázquez. The painting “Melting Clouds” is reminiscent of Soviet avant-garde photographer Alexander Rodchenko’s photo taken in Pushkino: it depicts pine trees captured from the same angle. Bulatov’s forest landscape is not supplemented by any text, but the tips of the pine trees, stretching upwards, evoke anxiety and premonitions of the approaching danger.

8. “Louvre. La Gioconda”, 1997-1998

At the end of the 1980s, Bulatov began to garner overseas recognition. His exhibitions were held in the Centre Pompidou and in Kunsthalle Zürich. In 1989, with his wife Natalia, Bulatov moved to New York, and then to Paris, where he still lives today. He didn’t emigrate, as he emphasizes himself, but rather, he simply changed his place of work. The painting “Louvre. La Gioconda” embodies his reflections and musings about the essence of art; only there’s a definite border between the viewers and the masterpiece of da Vinci.

9. “Painting and viewers”, 2011-2013

Bulatov considers Alexander Ivanov, a leading 19th century artist, to be the main painter in Russian art history. His masterpiece “The Appearance of Christ Before the People” hangs in the Tretyakov Gallery, and Bulatov believes it was created in such a way that there’s always someone in front of the painting; the canvas itself was carefully made such that it ‘swallows’ everything inside. In 2011, the artist decided to reinterpret and extrapolate on Ivanov’s painting, creating the work “Painting and Viewers”, where we see gallery visitors mix with the crowd who watches the appearance of the Savior and looking at John the Baptist. In this painting, the border between art and reality disappears.

10. “Everything's Not So Scary”, 2016

In spring 2022, Bulatov was one of the first artists invited to work at the art residence known as The Foundry in a former defense factory in a small village in the south of France. Owned and run by Russian artist Andrei Molodkin, Bulatov was invited to display some of his works, but not paintings. At the Foundry, Bulatov exhibits giant installations and art objects; among them is “Exit” and “Everything's Not So Scary”. The two-meter-tall words rise to a height of four floors, filling the entire space. They’re illuminated by the light pouring through the windows on the roof. The work inadvertently causes anxiety, but also offers hope that everything will get better.