How oil and gas improved relations between the USSR and West Germany

The first steps

In the 1950s, the Soviet Union and FRG established trade relations, signing an agreement on trade turnover and payments. The initiative came up against many obstacles, however. Politically, its durability was tested by crises in East-West relations, including the hardline foreign policy of the Soviet Union, as well as the hostility of a part of the West German leadership towards Moscow. From a practical point of view, West German companies had to deal with the bureaucracy and lack of flexibility inherent in the Soviet planned economy.

Chancellor Willy Brandt gives a governmental statement in the German Bundestag in Bonn on the 28th of September in 1969.

Chancellor Willy Brandt gives a governmental statement in the German Bundestag in Bonn on the 28th of September in 1969.

On the whole, however, Moscow treated West German entrepreneurs very favorably, appreciating their "promptness and meticulousness", as the former director of the Federal Institute for Eastern and International Studies in Cologne, Heinrich Vogel, observed in his article "Rapprochement through trade - German companies in Russia, 1950-1990".

The Soviet Union mainly supplied raw materials to West Germany: coal, timber, cotton and oil. In this sense, the 1956 Suez Crisis, which forced the Western powers to seek alternative sources to replace Middle Eastern ones, worked in Moscow's favor. West Germany in turn sold the USSR machine-tools, cast iron, and steel products, including pipes for the pipelines that Moscow was laying to supply the Socialist countries. Contracts for pipes signed with Mannesmann, Phoenix-Rhein Ruhr, Krupp, Siemens, Thyssen and other major West German companies (these made up the bulk of bilateral trade) were worth many millions.

Chancellor Willy Brandt and the Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin sign The Moscow Treaty on non-violence and cooperation between the FRG and USSR. August 12, 1970, Moscow.

Chancellor Willy Brandt and the Soviet Prime Minister Alexei Kosygin sign The Moscow Treaty on non-violence and cooperation between the FRG and USSR. August 12, 1970, Moscow.

In 1963, this cooperation was suspended due to tremendous pressure from Washington: The Cold War was gaining momentum and the Cuban Missile Crisis had just occurred, bringing the world to the edge of nuclear war. This unpopular decision by West German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer meant tremendous losses for German companies, so there was a cooling of relations between entrepreneurs and the ruling CDU/CSU party alliance.

'Deal of the century'

Pictured L-R: State Secretary in the Federal Chancellery Egon Bahr, Chancellor Willy Brandt, Foreign Minister Walter Scheel, Government Spokesman Rüdiger von Wechmar and State Secretary in the Federal Foreign Office Paul Frank on Red Square in Moscow.

Pictured L-R: State Secretary in the Federal Chancellery Egon Bahr, Chancellor Willy Brandt, Foreign Minister Walter Scheel, Government Spokesman Rüdiger von Wechmar and State Secretary in the Federal Foreign Office Paul Frank on Red Square in Moscow.

In the same year, the Chancellor resigned, to be replaced in 1969 by Willy Brandt with his "New Eastern Policy" (Neue Ostpolitik), which was much more conducive to dialogue with the Socialist countries. "Our national interests do not allow us to stand between West and East, our country needs cooperation and coordination with the West, and understanding with the East," said the Chancellor.

Trade with the East was no longer as closely linked to politics as before. While in 1968 West Germany’s total turnover with the USSR was $567 million, by 1969 it had reached $740 million, Heinrich Vogel points out in the article.

Signing of the first contract for natural gas supplies from the USSR to the FRG. February 1, 1970, Essen, Germany, conference room of the Kaiserhof Hotel.

Signing of the first contract for natural gas supplies from the USSR to the FRG. February 1, 1970, Essen, Germany, conference room of the Kaiserhof Hotel.

On Feb. 1, 1970, a historic agreement was signed in Essen, Germany - it was considered the deal of the century and was dubbed "gas for pipes". West Germany would supply the USSR with equipment for the construction of a pipeline to Western Europe in exchange for gas from newly-discovered fields in Western Siberia. The parties to the contract on the German side were the Mannesmann and Ruhrgas concerns. The former produced pipes and the latter sold Soviet gas in West Germany. Deutsche Bank financed the deal with a 1.2 billion DM credit. Gas deliveries began three years later.

This marked the start of energy cooperation between Bonn and Moscow, which assumed even greater significance following the outbreak of the Yom Kippur War between a coalition of Arab states and Israel in October 1973. The conflict had serious consequences for the West as the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries adopted an embargo on exports to countries that supported Israel. The conflict in the Middle East led to radical changes in energy policies, not only in West Germany but also in other Western European countries. One way to reduce reliance on Middle Eastern oil was to increase oil and gas purchases from the USSR.

A shop of the new Mannesmann AG factory producing large-diameter pipes for gas and oil pipelines to be delivered to the USSR. Mülheim, Federal Republic of Germany.

A shop of the new Mannesmann AG factory producing large-diameter pipes for gas and oil pipelines to be delivered to the USSR. Mülheim, Federal Republic of Germany.

The willingness of the two states to opt for political cooperation was manifested in the signing of another historically important treaty, the Treaty of Moscow of August 12, 1970 - the first result of the German chancellor's Neue Ostpolitik. Willy Brandt and Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev expressed their commitment to the goals of detente and the maintenance of international peace. The document was the springboard for the establishment of relations of neighborliness and cooperation between West Germany and the Soviet Union, and also laid the foundation for subsequent accords and agreements that were ultimately ultimately lead to the unification of Germany.

Secret talks

In 1979, not long before Christmas, a secret meeting was convened in the monumental Gosplan building adjacent to Red Square. On one side sat three German bankers, and on the other Nikolay Baybakov, the chairman of Gosplan, which was the government body tasked with planning and overseeing the development of the USSR's national economy.

"I trust they will never find out I am showing you this," he said, directing his pointer at a map of Europe and Asia, at the bottom of which I could clearly see a stamp with the words: "Secret. General Staff of the USSR Armed Forces."

On the map was a detailed diagram of further gas expansion that was to be a key factor in the peaceful program of cooperation. What stuck in our memory was the pipelines running from the Yamal Peninsula in Eastern Siberia to Uzhgorod in Western Ukraine, and we could see their future political significance." That was how one of the German participants recalled the meeting.

Mannesmann pipes are installed at one of the sections of the Urengoi-Uzhgorod gas pipeline.

Mannesmann pipes are installed at one of the sections of the Urengoi-Uzhgorod gas pipeline.

What was proposed was a second gas pipeline project. The same participants as before were invited to take part in the high-risk initiative - Mannesmann, Ruhrgas and Deutsche Bank. A credit of 10 billion DM - a hitherto unprecedented amount in international relations - was discussed. No interpreter was allowed into the preliminary talks at the central board of Deutsche Bank in Düsseldorf because of the extreme level of secrecy.

Initially the talks made rapid headway, but the international situation once again inhibited the prospects for cooperation. At the turn of the 1970s/1980s, the confrontation between the Western and Eastern blocs came to a head once more: The USSR sent troops into Afghanistan, and the U.S. under recently elected President Ronald Reagan was pursuing a harder line towards the Soviet Union.

Soviet officials and the Germans laying the first stone in the foundation of the future building of Deutsche Bank representation in the USSR.

Soviet officials and the Germans laying the first stone in the foundation of the future building of Deutsche Bank representation in the USSR.

Washington's hardline stance and its attempts to impose an embargo on the delivery of equipment for the construction of the gas pipeline became the main stumbling block in the project’s realization. The European countries were the USSR's equipment suppliers on the project, and they did not back the hardline position of the U.S. and refused to adopt its restrictions. Despite criticism, the previous secret discussions became open and official, and the project moved forward. This was in large measure thanks to the opening of a Deutsche Bank office in Moscow as early as March 1973.

After a long standoff between Chancellor Helmut Schmidt and his successor Helmut Kohl on the one hand, and President Reagan on the other, the project was scaled back, but implemented nevertheless. In 1989, the Yamburg gas pipeline entered into service.

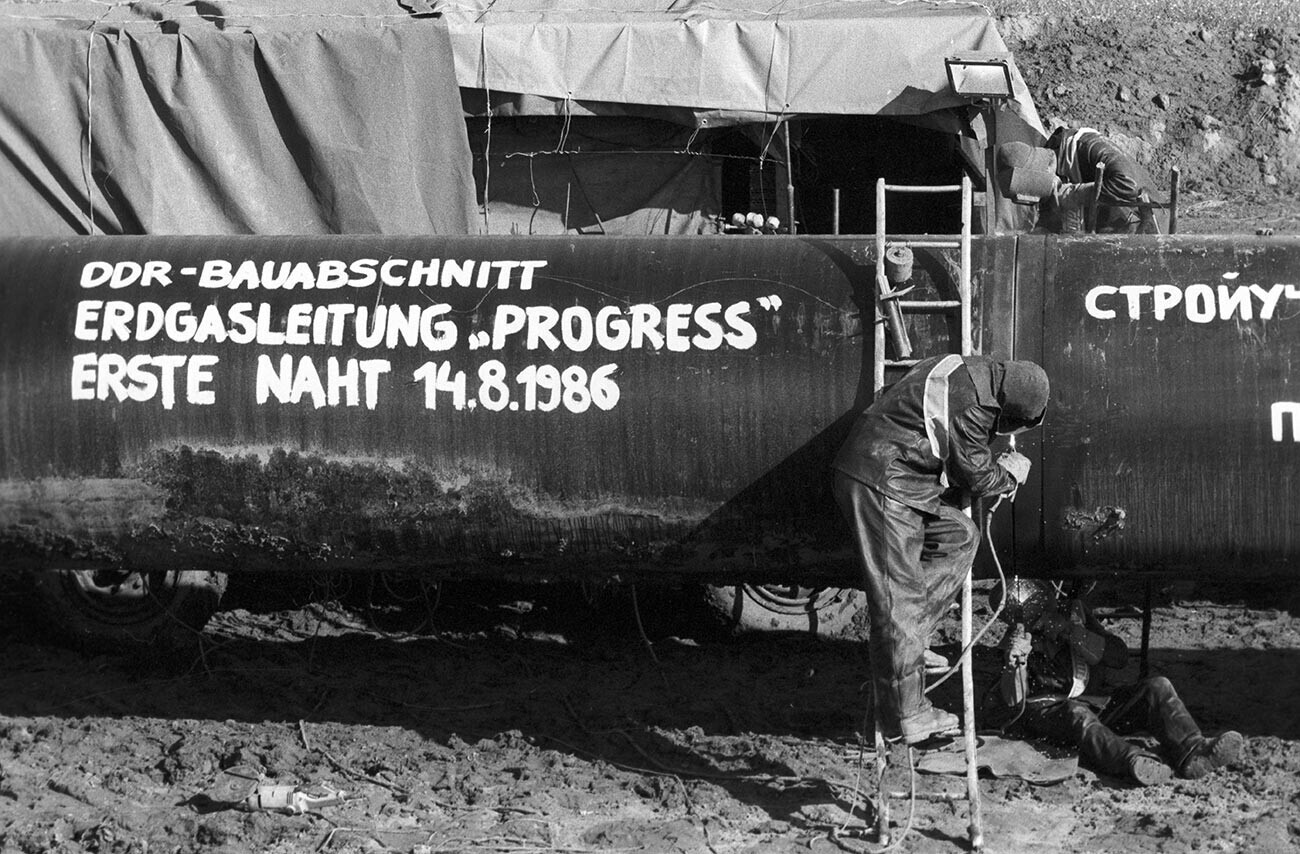

The first weld at the "Progress" (Yamburg) gas pipeline.

The first weld at the "Progress" (Yamburg) gas pipeline.

Right up until 1990 West Germany held the top spot in the USSR's trade with capitalist countries. By that time the period known as Perestroika - large-scale political and economic reforms - had already been under way for several years. Simultaneously, the Soviet economy faced a downturn, and in 1991 the USSR collapsed, opening up new opportunities for German businesses in the post-Soviet republics.