How Soviet linguists created a writing system for the Far North’s indigenous peoples

More than 40 smaller indigenous peoples live in the Russian Far North. You can find an unbelievable diversity of languages, which are not similar to each other, on the vast territories spread across the country. Just a century ago, the majority of these languages didn’t even have their own writing system.

The elimination of illiteracy

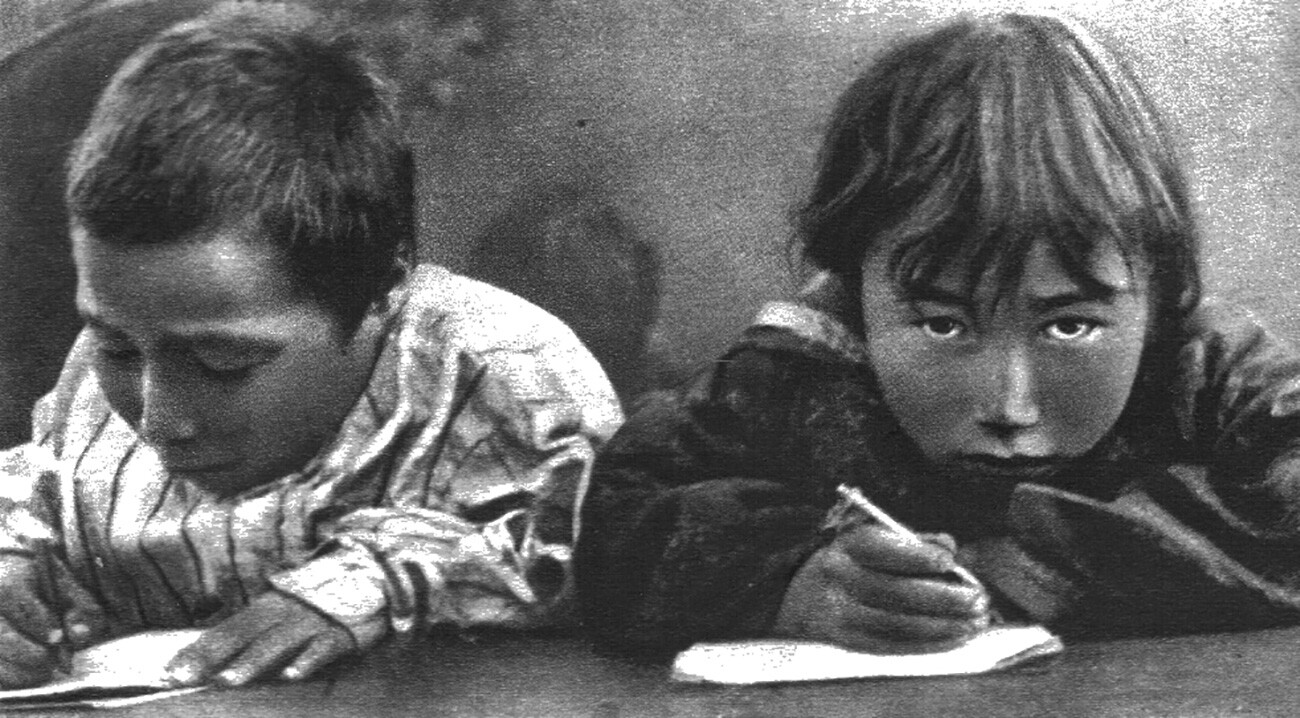

Young Chukhi students in school.

Young Chukhi students in school.

Russia has always been a multinational and multilingual country, however universal education only became accessible to its citizens after the 1917 Revolution. At the beginning of the 20th century, only 20-30% of the inhabitants of Russia could read and write; in Siberia, these numbers were significantly lower.

Eskimo school at South Head, Siberia.

Eskimo school at South Head, Siberia.

According to the 1919 decree ‘On the liquidation of illiteracy in the RSFSR’, the entire population of the country was obligated to learn how to read and write. One could choose either the Russian language or another, ethnic one. The new authorities needed this policy of indigenization, as historians say, to receive support not just among the Russian population but also among other peoples. Study guides were released (for adults, as well) in 40 different languages, including the Chuvash, Tatar and Uzbek languages.

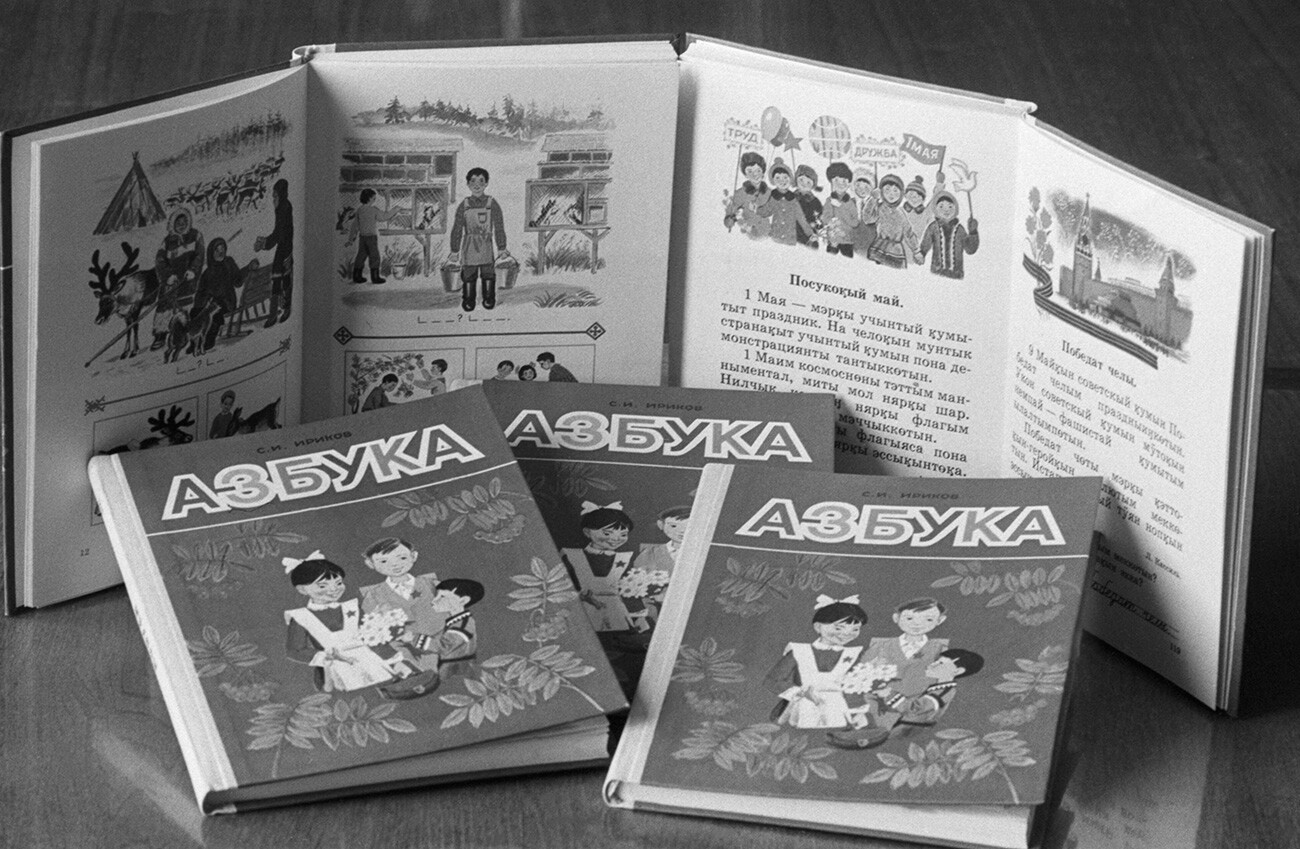

First primer books for Selkup students.

First primer books for Selkup students.

All of this sparked scientific research of the rare languages of the peoples of Russia, many of which didn’t even have a writing system. Although there were attempts to create it back in the 19th century, only the systematic approach of Soviet scientists bore fruit.

Unified northern alphabet

In the 1920s, Soviet scientists distinguished 26 indigenous small-numbered peoples of the North with a combined population of slightly more than 135,000 people. The majority were engaged in reindeer herding and sea animal hunting. They belonged to different language families, which further split into a variety of dialects.

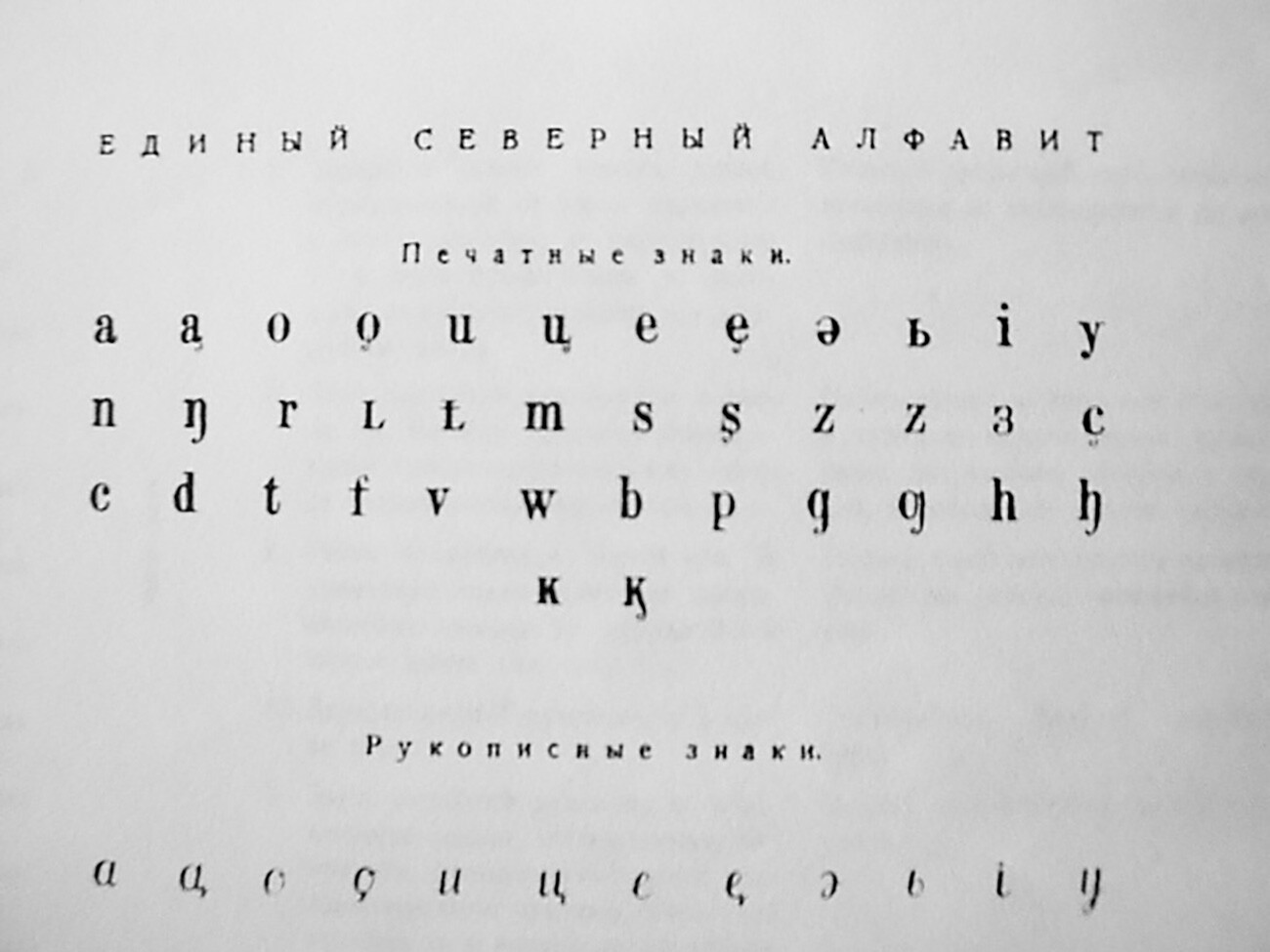

Unified northern alphabet.

Unified northern alphabet.

The Northern Faculty (founded in 1926) of the Leningrad Institute for Eastern Studies (from 1930 – the Institute of the Peoples of the North) was dedicated to solving this non-trivial linguistic task. In 1929, the specialists from this institute devised the Unified northern alphabet. Initially, it was based on the Latin script with additional letters and diacritics and was used for 16 languages of the Northern peoples (the Sámi, Nenets, Selkup, Mansi, Khanty, Evenki, Even, Nanai, Udege, Itelmen, Chukchi, Koryak, Eskimo, Aleut, Ket the Nivkh languages). Of course, different alphabets used a different amount of letters and glyphs, while one single most popular dialect for each of them was established as the “literary” one, but this common foundation significantly simplified the preparation of study guides.

The way to school in Chukotka.

The way to school in Chukotka.

But, in the middle of the 1930s, the language policy changed direction. Now, all the alphabets were to be swapped for Cyrillic ones (read more here) and the schools began to emphasize the study of the official state language. As a result, many indigenous languages were not transferred to the Cyrillic script; then they were practically removed from the educational program. Literature and newspapers in these languages were no longer published. In addition, in the 1960s, oil and gas fields began to be actively developed in the North, where specialists from all republics came, and the Russian language became the common language of communication. However, some “northern” words migrated to everyday life. For example, the word ‘parka’ (‘coat’) comes from the Nenets language.

The school in the Chukchi settlement of Konergino.

The school in the Chukchi settlement of Konergino.

The scientific interest towards the northern languages began to be revived only in the 1970s-1980s. Linguists again went on scientific expeditions to the northern peoples.

Gertsen Leningrad Pedagogical Institute, now - Institute of Northern Peoples, St. Petersburg. 1977.

Gertsen Leningrad Pedagogical Institute, now - Institute of Northern Peoples, St. Petersburg. 1977.

In 1988, the Tofa language acquired its own official writing system; in the 1990s, the Aleut language got one and, in 2003 – the Chulym language (that’s the language popular ethno-band OTYKEN sings in).

How are northern languages studied today

Modern linguists distinguish about 40 small-numbered indigenous peoples of Siberia and the Far East; not everyone among them knows their native languages. For example, from 50,000 Nenets, every second one knows their native language, but from 1,100 Kets only about 150 know the Ket language; from 200 representatives of the Orok people (or Uilta) less than 50 know the language. And only three people officially speak the Tofa language fluently! Meanwhile, the age of the native speakers is rising rapidly. Linguists note, however, that there are a lot of bilingual people among the northern peoples.

Kids near the village of Kanchalan, Chukchi Autonomous District.

Kids near the village of Kanchalan, Chukchi Autonomous District.

In schools in the north, native languages began being taught again at the end of the 1980s; however, only in primary school or as an elective. Some regions have language courses for adults, as well, both in person and online.

As for today, only one northern language is left without a writing system – the language of the Enets people on the Taymyr Peninsula, the population of which amounts to no more than 300 people (with 40 people being native speakers). Since 2018, linguists from the Siberian Federal University in Krasnoyarsk have been developing the official writing system for the Enets language.

School in Eveno-Bytantaisky national ulus (district), Yakutia.

School in Eveno-Bytantaisky national ulus (district), Yakutia.

Northern languages are also being studied in Tomsk State Pedagogical University and in Moscow State University. But, the teachers of the rarest northern languages in the world are trained in the Institute of the Peoples of the North. Only there can one learn Itelmen, Dolgan, Orok and other languages, the native speakers of the most remote settlements of Russia.