How did Tsar Nicholas II become a saint?

In 2017, the famous Russian director Alexei Uchitel made a film called ‘Matilda,’ in which the soon-to-be Tsar Nicholas II was shown as a careless young man having a frivolous affair with the famous prima ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya. Even before the film was released, many Orthodox believers felt offended. They perceived a credible historical episode as an insult to the memory of the Tsar-saint who was canonized in 2000.

A still from the 'Matilda' movie

A still from the 'Matilda' movie

Orthodox activists staged protests against ‘Matilda’ at movie theaters and led processions with icons of the royal family members. The Russian Orthodox Church (ROC) found itself in a difficult situation. On the one hand, Nicholas II was a historical figure from the fairly recent past who was not alien to human foibles and could easily become a character in Russian cinema. But on the other hand, he was a saint with his icons prayed to in churches throughout Russia.

A single-person picket against Alexei Uchitel's film Matilda before its premiere in Moscow, 2017

A single-person picket against Alexei Uchitel's film Matilda before its premiere in Moscow, 2017

On second thought, the ROC hierarchy did not support the scandal. Tikhon Shevkunov, an influential Orthodox bishop, chairman of the Patriarchal Council on Culture, and a member of the Supreme Church Council of the Russian Orthodox Church urged all believers to treat ‘Matilda’ as a “fantasy film”.

The ROC has never before had to grapple with such a controversial and unusual problem. The Tsar was canonized not for his spiritual qualities but as a martyr, which meant that his mortal suffering outweighed his purely human faults and wrongdoings. However, this view was not understood even within the ROC’s clergy, much less by Russian society, a significant part of which felt that Nicholas II was to blame for the empire’s demise.

Execution and prerequisites for canonization

Nicholas II abdicated on March 2, 1917, during the February Revolution (which preceded the October Revolution when the Bolsheviks took power). After his abdication, Nicholas spent nearly six months under house arrest in his residence at Tsarskoye Selo and then was exiled with his family to Tobolsk in Siberia, finally moving to Yekaterinburg. There on the night of July 17, 1918 the Bolsheviks shot him dead along with his wife, five children, a cook, a medic, a maid of the Tsarina and the Tsar’s valet.

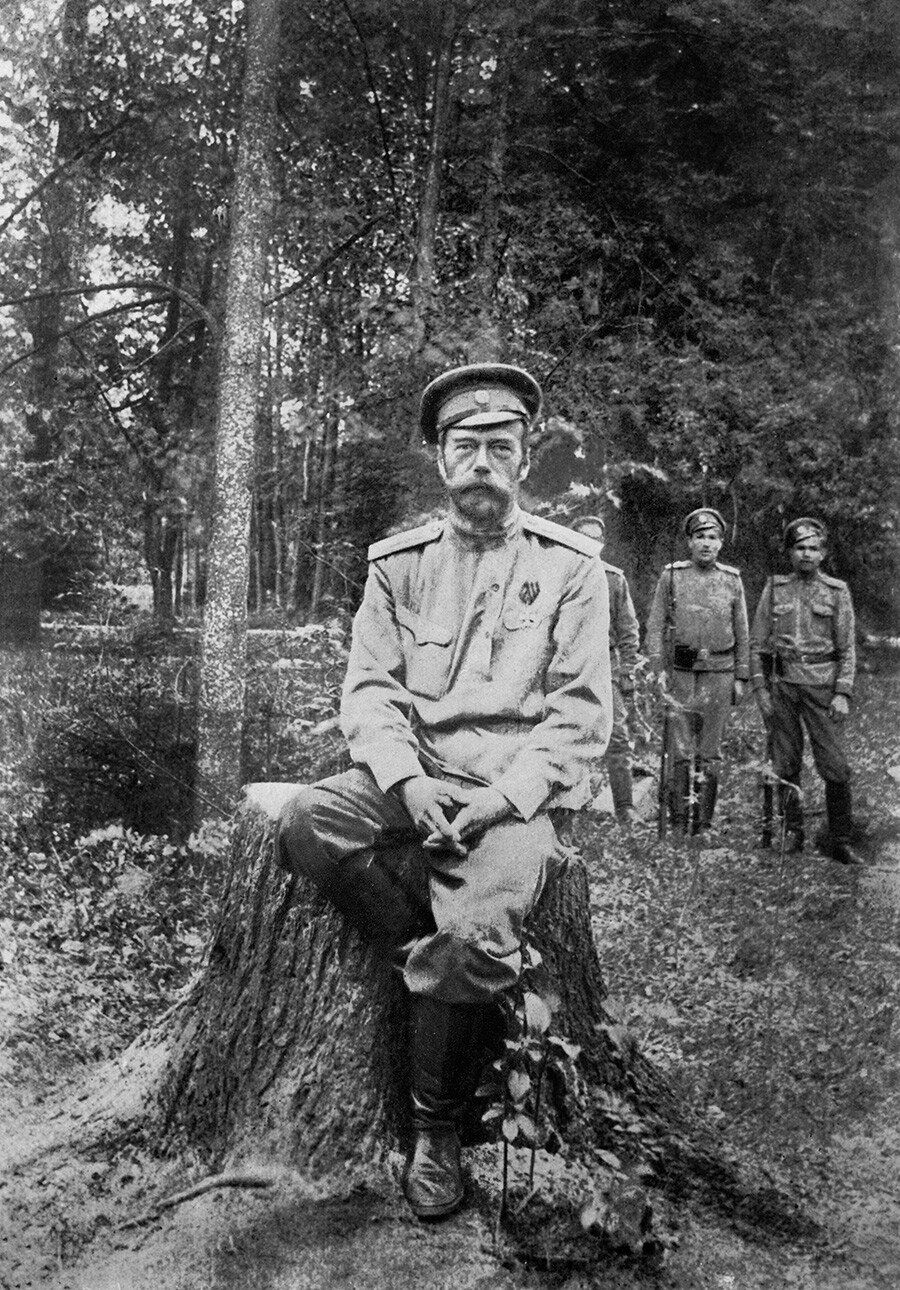

Nicholas II after throne abdication, under guard in Tsarskoye Selo, 1917

Nicholas II after throne abdication, under guard in Tsarskoye Selo, 1917

Immediately after the family’s massacre, talk of canonization began to emerge among Russian Orthodox believers for whom the Tsar was God’s anointed one, and such a brutal murder (especially including the Tsar’s children) was perceived by many as martyrdom. Churches throughout the country held funeral masses for Nicholas and his family. Patriarch Tikhon encouraged priests to perform memorial services and gave a passionate speech about the “spiritual feat” of the Tsar.

“We know that when he abdicated, he did so out of his love for Russia. He could have found safety and a relatively peaceful life abroad after his abdication, but he did not do so, wishing to suffer together with Russia,” said Tikhon.

For many years, despite the anti-religious policies of the Soviet state, Russian believers continued to honor the Tsar’s memory. The Russian émigré monarchists who had fled the country after the Revolution were particularly zealous. Heated discussions arose among them about the possibility of canonization.

In 1981 after much debate and discussion, the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (ROCA) canonized Nicholas II, his wife, children, and even his Catholic servant Aloysius Trupp, and Catherine Schneider, the Lutheran woman serving the Tsarina.

Royal Martyrs, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (including Dr. Evgeny Botkin, cook Ivan Kharitonov, servant Aloysius Troupe, maid Anna Demidova, and martyrs of the Alapaev mine)

Royal Martyrs, canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad (including Dr. Evgeny Botkin, cook Ivan Kharitonov, servant Aloysius Troupe, maid Anna Demidova, and martyrs of the Alapaev mine)

Canonization: con arguments

In the late 1980s, as Perestroika and the revival of the Russian Orthodox Church gained steam, discussions about the canonization of Nicholas II and members of his family began to grow more intense in Russia. From 1992 to 1997, the Russian Orthodox Church's Synodal Commission on the Canonization of Saints examined the grounds for canonizing the imperial family.

Nicholas II and his family, pictured left-right: Olga, Maria, Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, Anastasia, Alexei, and Tatiana, 1913

Nicholas II and his family, pictured left-right: Olga, Maria, Empress Alexandra Fyodorovna, Anastasia, Alexei, and Tatiana, 1913

The Commission carefully considered the many arguments against canonization.

- Firstly, many perceived the abdication of “God's anointed” as an ecclesiastical crime: he left his “flock” unattended, and this gave rise to a bloody civil war that ruined Russia. However, the commission had a rebuttal: “He was afraid that his refusal to agree to abdication could lead to a civil war. The Tsar did not want a drop of Russian blood to be spilled because of him,” says the final report of the commission’s head, Metropolitan Juvenaly.

- Secondly, opponents of canonization pointed to the anti-clerical communication of the imperial family with Grigory Rasputin, who mystically helped to stop the bleeding of the hemophiliac Tsarevich Alexei and was able to calm the tantrums of the Empress.

- Thirdly, an important argument prior to the decision to canonize was the lack of miracles associated with the royal family and their remains. However, in the 1990s, various church authorities began to receive reports of miracles, healings, and other “gracious help” through prayers to the imperial martyrs.

Canonization: pro arguments

At the same time, the commission reviewed arguments from supporters of canonization.

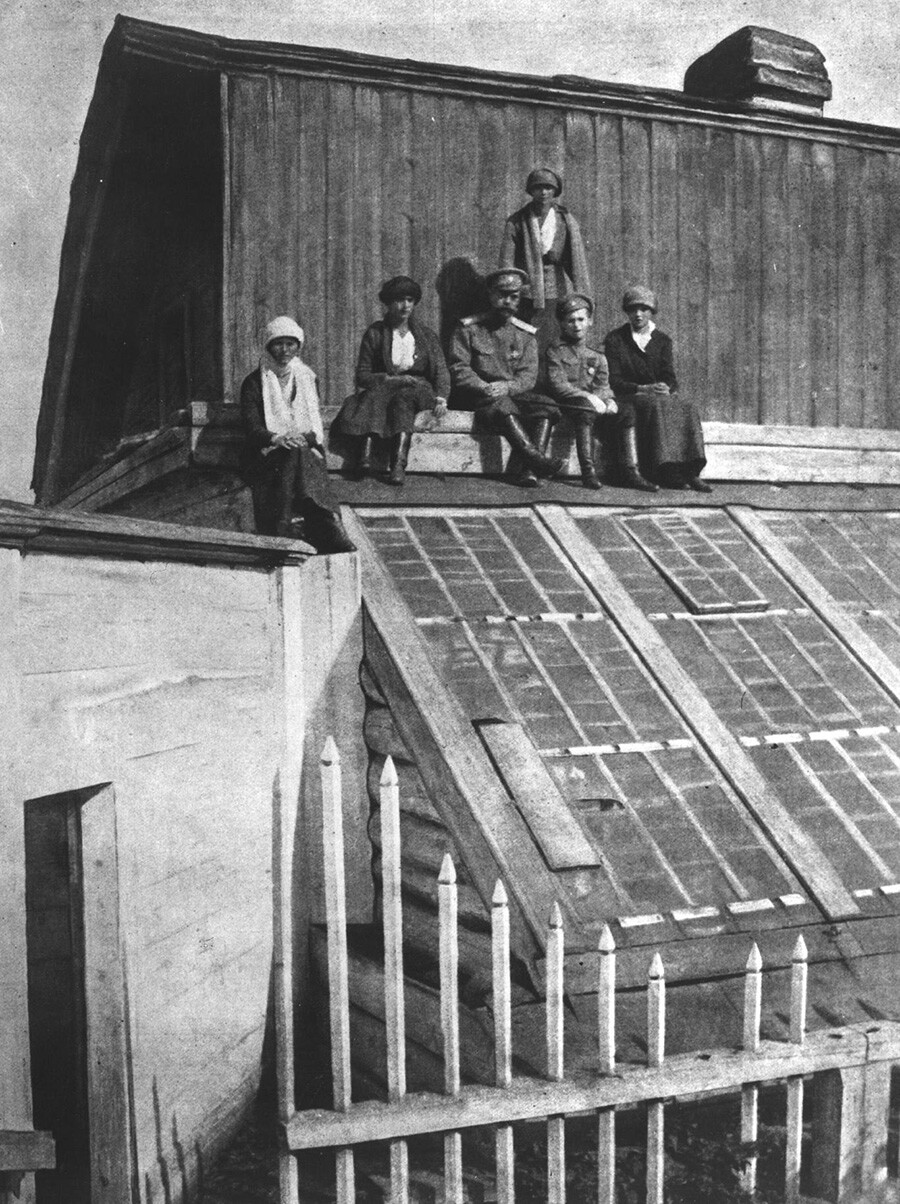

Nicholas with kids sitting on the roof of a greenhouse during their captivity In Tobolsk, 1918

Nicholas with kids sitting on the roof of a greenhouse during their captivity In Tobolsk, 1918

- Firstly, the abundant appeals of believers in support of canonization, signed by several thousand individuals, both clerics and laity.

- Secondly, the deep piety of the imperial family and, in particular, of the Tsarina (a German princess who had converted to Orthodox Christianity for her husband) was seen as a PRO argument. This made them stand out among the members of the aristocracy, many of whom in the late imperial era had largely distanced themselves from the official church. “The upbringing of the children of the Imperial Family was permeated with a religious spirit,” and the Empress' righteous way of life was also mentioned. The fact that “the letters of Alexandra Feodorovna reveal the depth of her religious feelings – spiritual strength, grief about the fate of Russia, faith, and hope for God's help.” In addition, the Empress and her daughters worked as nurses caring for the wounded during the First World War.

- Thirdly, according to the Russian Orthodox Church, Nicholas II paid great attention to the Church's needs, and donated generously to the construction of churches and monasteries, and initiated the canonization of many well-regarded saints, for example, Seraphim of Sarov.

Still, many believed that the death of Nicholas II and his family could not be recognized as a martyr’s death in the name of Jesus Christ. However, according to some evidence, during their last period of life in prison the imperial family often read the Gospel and led a devout and humble life, despite the abuse and insults of the Bolsheviks.

The basement of the Ipatiev house where the Romanov family was killed

The basement of the Ipatiev house where the Romanov family was killed

Hence, it was proposed that the family should be canonized as “holy martyrs” who “followed Christ's path and patiently endured physical and moral suffering and death at the hands of political opponents.”

“In the comprehension of this feat of the Royal Family,” the commission unanimously approved canonization. On August 20, 2000, in the Cathedral of Christ the Savior in Moscow, the martyrs of the early Russian twentieth century, including the entire royal family, were glorified. Emperor Nicholas II, Empress Alexandra, Tsarevich Alexei, Grand Duchesses Olga, Tatiana, Maria, and Anastasia were canonized as “martyrs.”

Hidden motives for canonization

As Juvenaly stated in his final report, “the canonization of the Monarch is in no way connected with monarchist ideology and does not denote the ‘canonization’ of the monarchical form of government.”

The Church of All Saints on Blood in Yekaterinburg was built in early 2000s on the site of the Ipatiev House where the tsar's family was killed

The Church of All Saints on Blood in Yekaterinburg was built in early 2000s on the site of the Ipatiev House where the tsar's family was killed

“The Church's position here was quite clear: it was not the image of Nicholas II's reign that was canonized, but the image of his death and departure from the political arena,” the renowned theologian and deacon Andrei Kuraev said in an interview. “After all, he had every reason to become bitter, furious, to boil over with anger and accuse everyone and everything in the last months of his life while he was under arrest. But none of this happened.”

In addition, Kuraev believes that this broad gesture meant a kind of summing up of the terrible 20th century for Christianity.

A central motive for canonization was also the reconciliation of the Russian priesthood in Russia and abroad. In the 1990s, the question of the unification of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad and the Russian Orthodox Church arose on the initiative of the Moscow Patriarchate.

Monastery in Ganina Yama, outside Yekaterinburg, where the bodies of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his family were buried (actually thrown into a pit)

Monastery in Ganina Yama, outside Yekaterinburg, where the bodies of Tsar Nicholas II of Russia and his family were buried (actually thrown into a pit)

For the ROCA, the sanctity of the imperial family was already an unshakable truth, and therefore, as Biblical scholar and writer Andrei Desnitsky wrote in 2000, “recognition of the sanctity of the imperial family was designated by the hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church Abroad as a necessary condition for reconciliation with the Russian Orthodox Church.”