How the assassination of Stalin’s friend triggered the ‘Great Terror’ in the USSR

On December 1, 1934, a murder took place in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg) that shocked the entire Soviet Union. Sergei Kirov, first secretary of the Leningrad Regional Party Committee and City Party Committee (de facto chief of the city), a close ally and friend of Stalin, was shot dead.

The crime was one of the main triggers for the start of the massive wave of political repression in the USSR, infamously known as the ‘Great Terror’. It still remains a mystery, however, whether the assassination was motivated by personal revenge on the part of a desperate loner or whether it was plotted in the country’s highest echelons of power.

High-profile crime

Thirty-year-old Leonid Nikolayev was waiting for Kirov at half past four in the afternoon outside his private office in the Smolny Institute, the building in which the city administration was housed. He killed the official with a single shot to the back of the head and then tried to shoot himself, but was prevented from doing so by witnesses to the crime who got to him in time.

Sergei Kirov.

Sergei Kirov.

It turned out that the murderer was a member of the Bolshevik Party who had once worked for the authorities himself, but had been dismissed because of his propensity for constant arguments. Having failed to find a job, Nikolayev spent a long time filing complaints and petitions to his superiors (including Kirov), but all in vain.

Apart from resentment, another motive for the crime could have been jealousy. The investigation established that Nikolayev suspected his wife, Milda Draule, who also worked at the Smolny Institute, of having an affair with Kirov.

The Smolny Institute.

The Smolny Institute.

Previously, on October 15, the first secretary’s guards had detained Nikolayev with a revolver outside Kirov’s house, but, after checking his firearm certificate and party membership card, let him go. The same card helped the murderer get into the Regional Party Committee building unchallenged on the fateful day on December 1.

Personal record

As early as the morning of December 2, a train carrying members of the Soviet government arrived in Leningrad from Moscow. “You didn’t keep him safe!” Joseph Stalin declared irritatedly to the delegation meeting him on the platform. At that time, he was secretary of the VKP(b) [All-Union Communist Party (Bolsheviks)] Central Committee, but had already essentially concentrated all the power in the country in his own hands.

Leonid Nikolayev and Milda Draule.

Leonid Nikolayev and Milda Draule.

“Sergei Mironovich Kirov was a great friend of the family from way back…” recalled Svetlana Alliluyeva, the daughter of the ‘Father of the Peoples’. “Kirov accompanied my father on vacation in the summer to Sochi and they used to take me with them. I still have a pile of photographs taken at that time, simple family photos with nothing posed about them… Kirov was closer to my father than [Alexander] Svanidze, all his relatives, [Stanislav] Redens or many of his other work colleagues. Kirov was close to my father and my father needed him.”

Stalin took personal charge of the Kirov case, closely followed the investigation and personally questioned witnesses. It was he who came up with the theory that a group of opposition members led by his opponent in the internal party struggle, Grigory Zinoviev, was behind the Kirov assassination. At the prompting of the supreme leader, this theory was immediately seized upon by the NKVD.

Crackdown

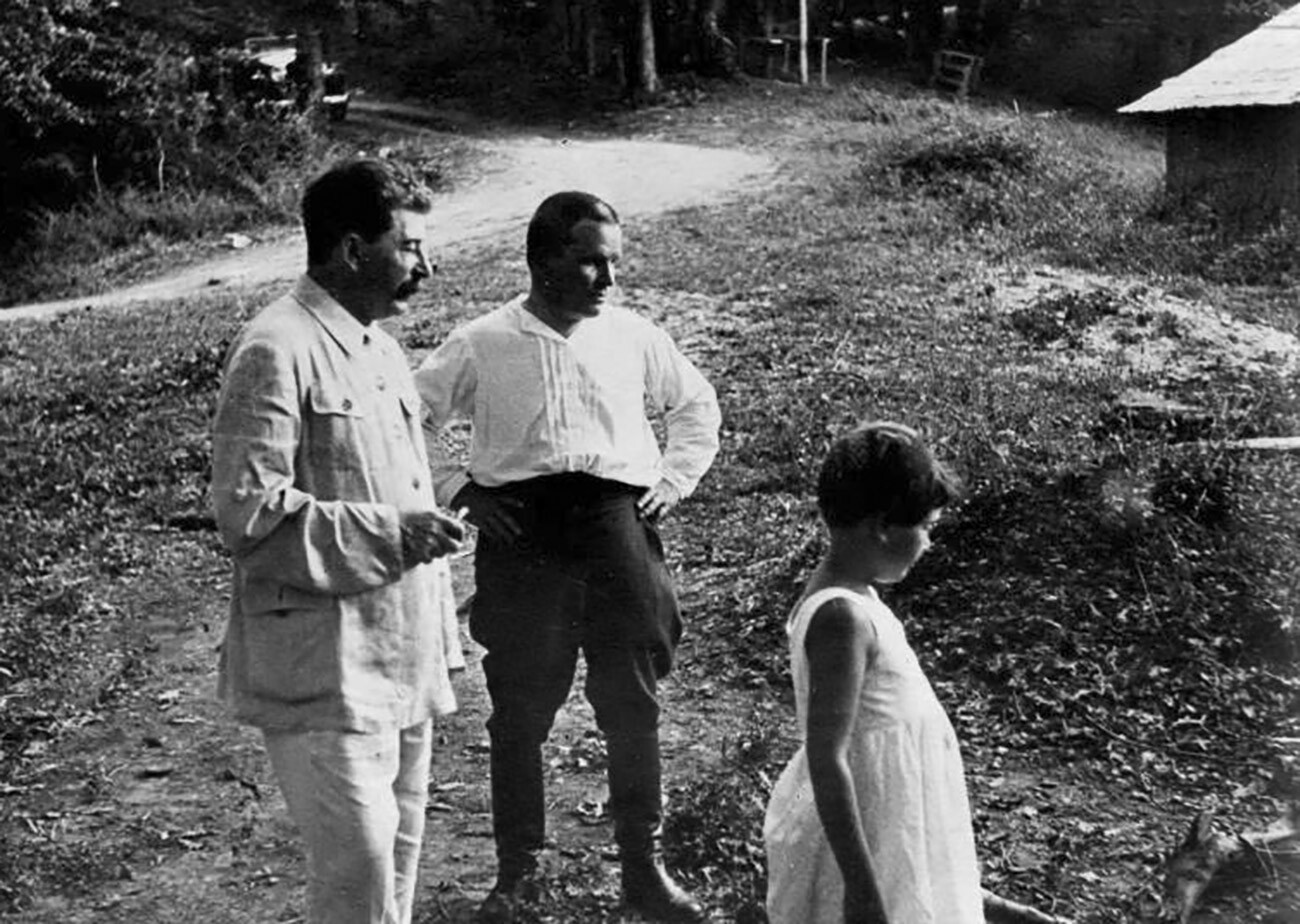

Stalin, his daughter Svetlana and Kirov.

Stalin, his daughter Svetlana and Kirov.

The following words were published in a leading article in the ‘Pravda’ newspaper on December 5: “The vile and underhand agents of the class enemy, the abject scum of the former Zinovievite anti-party group, have snatched Comrade Kirov from our ranks.”

Nikolayev was executed by firing squad on December 29 and Milda Draule, having been pronounced his accomplice, fell to the same fate soon afterwards. Over ten people were also sentenced to death, including Zinoviev and his ideological associate and colleague Lev Kamenev. Subsequently more than 800 of their supporters were subjected to repressions. None of them had been involved in the murder of Kirov.

Stalin and Kirov.

Stalin and Kirov.

Several hundred members of the local NKVD Directorate and the Leningrad Regional Party Committee and City Party Committee were transferred to other duties, dismissed or arrested “for their negligent attitude to their duties”. One way or another, they included all the witnesses to the tragic incident at the Smolny Institute. What is more, Kirov’s bodyguard, who had accompanied his boss to work on that fateful day, was killed in a road accident in mysterious circumstances at the very beginning of the investigation.

Flywheel of repressions

Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev, who, in 1934, had been first secretary of the Moscow City Committee of the VKP(b), was convinced that Stalin himself stood behind the organization of the murder: “Kirov was the sacrificial victim whose death was used to stir up the country and to get rid of people that didn’t suit Stalin, to dispose of the old Bolsheviks, by accusing them of having engineered the assassination of Kirov.”

Grigory Zinoviev.

Grigory Zinoviev.

“Of course, it was not Stalin himself who issued the order to Nikolayev,” Khrushchev wrote. “Nikolayev was too insignificant for that. But, I have no doubt that someone had primed him on Stalin’s orders… Nikolayev probably hoped for some sort of leniency. But, it was excessively naive of him to genuinely count on it. This Nikolayev was not so important an individual: He carried out his assignment and thought that his life would be spared. He was just a simpleton. After performing such an order the perpetrator inevitably had to be eliminated to hush up the truth. And, so, Nikolayev was eliminated.”

This theory has also had its opponents. “There are no documents or evidence confirming Stalin’s or the NKVD bodies’ involvement in the murder of Kirov,” wrote Pavel Sudoplatov, one of the heads of the Soviet intelligence services. “I am convinced that the killing of Kirov was an act of personal revenge.”

Kirov's funeral procession.

Kirov's funeral procession.

The extent of the ‘Father of the People’s involvement in the death of Kirov remains an open question today. Whatever the case, the Soviet leader skilfully used the incident to crush his political enemies and consolidate his own power.

In the wake of the high-profile crime, the NKVD bodies were given the right to fast-track the cases of those accused of preparing or carrying out “terrorist acts”, without lawyers or the possibility of appeals for clemency. Death sentences started to be carried out immediately after verdicts were pronounced. The flywheel of repressions started to pick up speed and it was only after Stalin’s own death that it was possible to halt it.