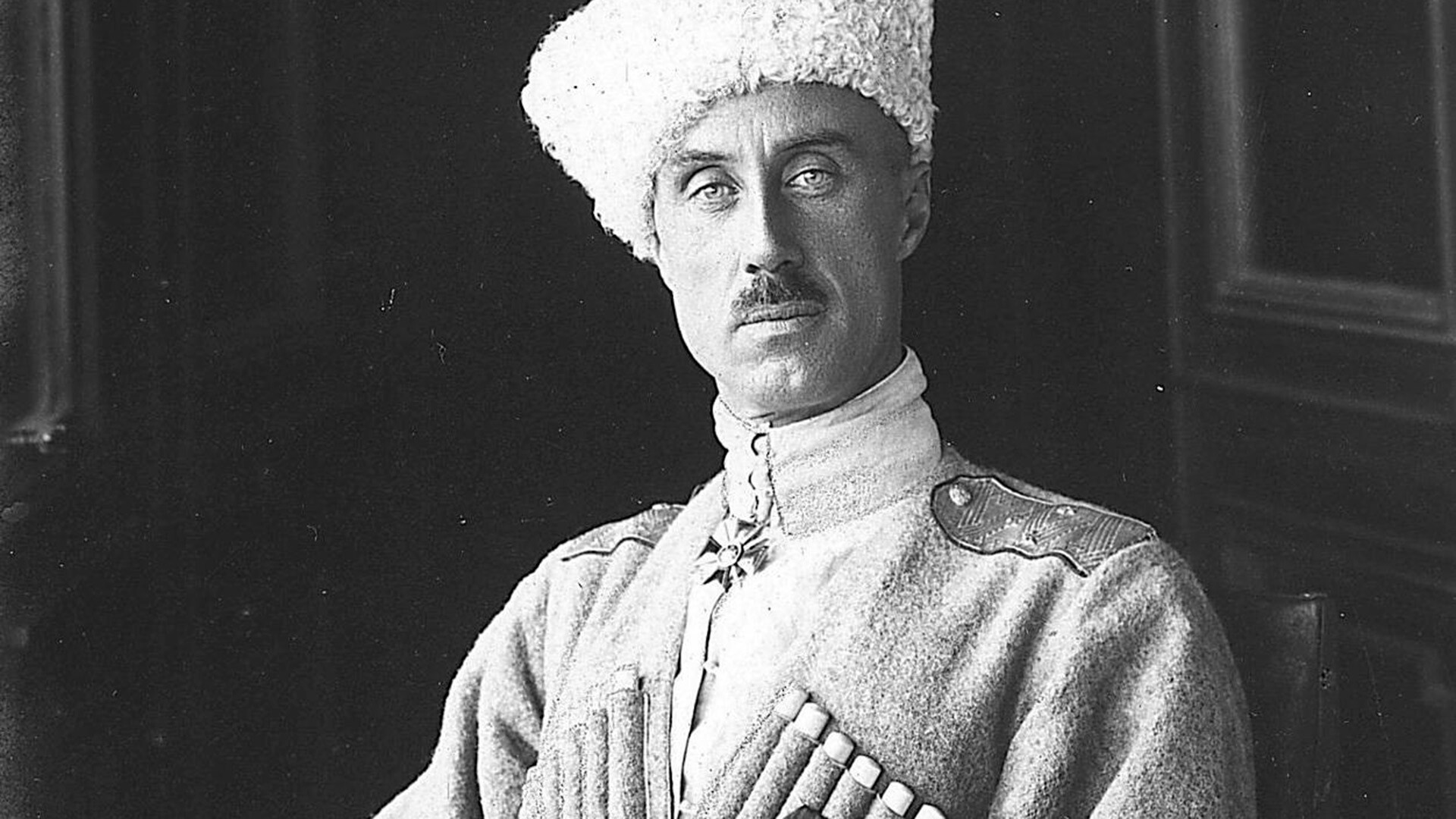

Baron Wrangel: The last serious enemy of the Bolsheviks

“Our further paths are full of uncertainty… May the Lord grant everyone the strength and wisdom to overcome and survive the Russian hard times,” Baron Pyotr Wrangel, one of the leaders of the anti-Soviet White movement in the Civil War in Russia, addressed his troops in November 1920.

The Russian army he led suffered a heavy defeat at the hands of the Bolsheviks and was hastily boarding ships to leave Russia forever. Its commander, the last major enemy of the Soviet power in that terrible conflict, was evacuated with it.

Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel descends the stairs of the Grafskaya Pier in Sevastopol for the last time, November 1920.

Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel descends the stairs of the Grafskaya Pier in Sevastopol for the last time, November 1920.

Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel came from an old Russified Danish family, many of whose members became famous serving Russia. The baron himself studied to be an engineer at the Mining Institute, but, later, chose a military career.

During the Russo-Japanese War, Wrangel rose to the rank of ‘sotnik’ (centurion, a commander of 100 men) and earned several awards for his bravery in battle. “In the Manchurian War, Wrangel instinctively felt that fighting was his element and combat work was his calling,” wrote General Pavel Shatilov, who served with him.

The headquarters group of the Transbaikal Division under the command of Major General P.K. Rennenkampf and the 2nd Argun Cossack Regiment. Ensign P. Wrangel, 4th from the left in the 1st row.

The headquarters group of the Transbaikal Division under the command of Major General P.K. Rennenkampf and the 2nd Argun Cossack Regiment. Ensign P. Wrangel, 4th from the left in the 1st row.

The baron was one of the first to be awarded in the Russian army during World War I. On August 19, 1914, near the village of Kauschen, he led a squadron and captured a German artillery battery with a daring attack.

“Then he brilliantly commanded cavalry units up to and including divisions,” noted Grand Duke Nikolai Romanov. By the end of the world conflict, the baron had risen to the rank of major general.

Attack of P.N. Wrangel with a squadron of the Life Guards Cavalry Regiment on a German battery on August 19, 1914.

Attack of P.N. Wrangel with a squadron of the Life Guards Cavalry Regiment on a German battery on August 19, 1914.

“This is the end, this is anarchy,” was how Wrangel responded to the collapse of the autocracy during the February Revolution of 1917. He advocated suppressing the revolution by military force, but had neither the authority nor the capabilities to do so.

After the October Bolshevik Revolution, the baron distanced himself from politics for a time and went to his family in Yalta, Crimea. He was arrested there, but was soon released.

Wrangel with his wife Olga.

Wrangel with his wife Olga.

Having miraculously escaped death, Wrangel decided to join the fight against the Soviet regime. In September 1918, he joined the ranks of the White Volunteer Army of General Anton Denikin, which would later become the Armed Forces of the South of Russia (AFSR).

As an experienced officer, the baron was given command of a cavalry division and then a corps. After he successfully defeated the Red forces in Kuban and the North Caucasus, he was given command of the Caucasian Volunteer Army.

The Armed Forces of the South of Russia.

The Armed Forces of the South of Russia.

On June 30, 1919, Wrangel's troops took Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad, now Volgograd), which the Whites had unsuccessfully stormed three times before. Here, on July 3, Denikin signed the ‘Moscow Directive’ on a decisive offensive on the capital.

The baron criticized the plan for the excessive dispersion of forces and the lack of maneuver, calling it "a death sentence for the armies of the South of Russia". Nevertheless, he and his troops took part in its implementation.

General P.N. Wrangel leaves the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral after the service. Tsaritsyn, October 15, 1919.

General P.N. Wrangel leaves the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral after the service. Tsaritsyn, October 15, 1919.

The Armed Forces of the South of Russia suffered a defeat and retreated to the Crimean Peninsula. Denikin resigned as commander-in-chief and, in April 1920, Baron Wrangel became commander-in-chief. On his initiative, the Armed Forces of South Russia were renamed the Russian Army.

Crimea, meanwhile, became the last stronghold of the White movement in the south of the country. Wrangel managed to reorganize the troops and took up domestic politics, trying to make the peninsula an example for the rest of Russia to follow.

The commander of the Russian army, General Wrangel, receives a report from a pilot of the 5th aviation detachment.

The commander of the Russian army, General Wrangel, receives a report from a pilot of the 5th aviation detachment.

In particular, the baron carried out land reform. The bulk of the landowners' land had been transferred to the peasantry for a ransom, which had to be paid to the state. The state, in turn, had to settle accounts with the owners of the alienated lands. However, Wrangel's regime did not achieve widespread support among the peasants with these measures.

In addition, Wrangel abandoned the main idea of the White movement — “a united and indivisible Russia” — and tried to establish military cooperation with various political centers that emerged on the territory of the destroyed empire. However, to no avail.

The Government of South Russia. Crimea, Sevastopol, 1920.

The Government of South Russia. Crimea, Sevastopol, 1920.

For a long time, Wrangel's Crimea held on, due to the fact that the Red Army was waging a difficult war against Poland. In early June 1920, the White troops even managed to invade the Northern Black Sea region and take control of a number of territories, which, however, they soon abandoned.

In the fall of the same year, the active phase of the Soviet-Polish war ended and the Bolsheviks threw all their forces at Wrangel. In November 1920, the Red Army broke through the White defensive lines on the Perekop Isthmus and stormed the peninsula. White Crimea was doomed.

Soviet military leaders Semyon Budyonny, Mikhail Frunze and Kliment Voroshilov (left to right) develop a plan to defeat the troops of White Guard General Pyotr Wrangel.

Soviet military leaders Semyon Budyonny, Mikhail Frunze and Kliment Voroshilov (left to right) develop a plan to defeat the troops of White Guard General Pyotr Wrangel.

Within three days, the Russian army, together with its commander and civilians who had fled from the Bolsheviks — about 146,000 people, in total — evacuated the peninsula with the support of the Entente fleets. After this, there were no more opponents of Wrangel's caliber left for the Soviet government in Russia.

In exile, Pyotr Wrangel created a large anti-Soviet organization – the Russian All-Military Union – which. in the mid-1920s. united up to 100,000 former White Guards. They were supposed to take part in the future war of the Entente against the Bolsheviks.

However, the baron never lived to see a new battle with the Red Army. He died suddenly in 1928 from tuberculosis; however, there is a theory that the Soviet special services had a hand in his death.

Evacuation of Wrangel's army from Crimea.

Evacuation of Wrangel's army from Crimea.