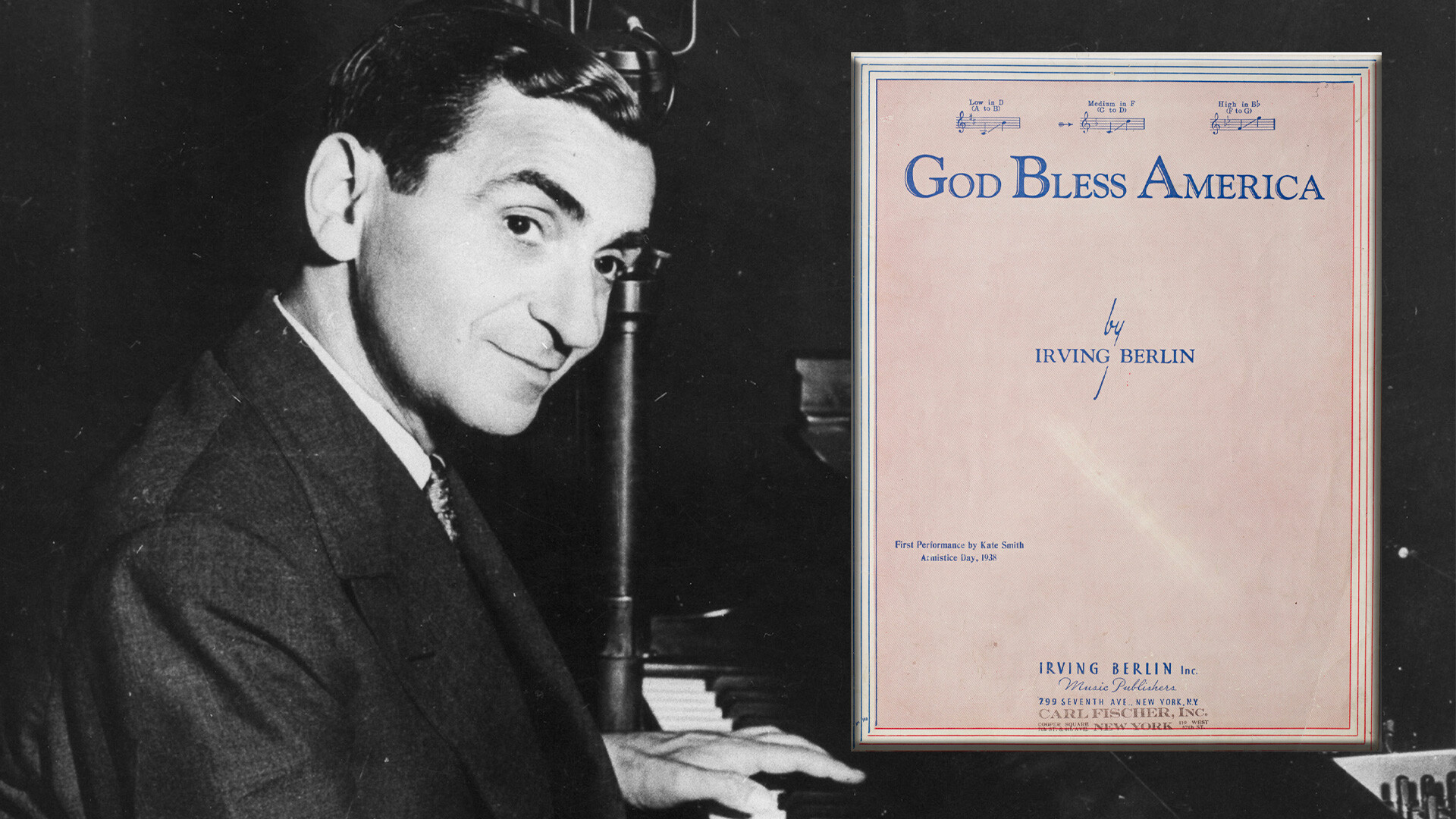

These American presidents once worked in Russia!

1. John Quincy Adams, 6th President of the United States, worked in Russia from 1809 to 1814.

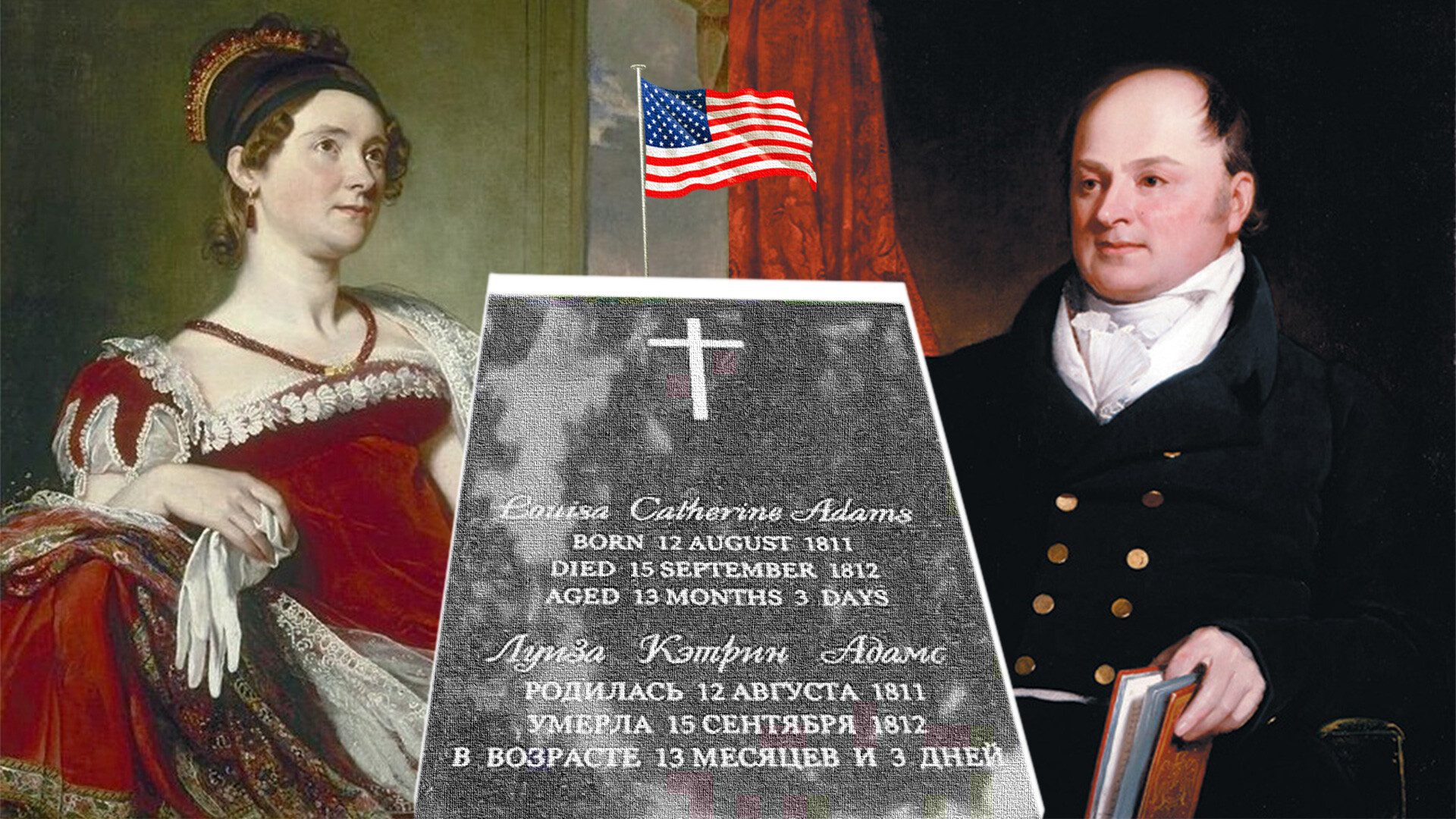

John Quincy Adams, by John Singleton Copley.

John Quincy Adams, by John Singleton Copley.

Adams Jr. first visited Russia at the age of 14: In 1781, he accompanied as secretary to Francis Dane, the first U.S. envoy to St. Petersburg, who, however, failed to present his credentials to Empress Catherine II.

The second time John Quincy came to the country was in 1809, already as the official U.S. diplomatic representative to Russia. He became the first “plenipotentiary envoy” to St. Petersburg. In his letters to his mother, he complained about the high cost of living in the Russian capital.

“You are acquainted with the difficulty, and the expense, of forming a suitable domestic establishment for an American minister in other parts of Europe. They are everywhere great. Here, they are greater than anywhere else. We are still indifferently lodged at a public house and very expensively. The attendances at Court are frequent and of the most indispensable obligation. It is most frequently twice in a day, the morning at a levee and the same evening at a Ball and Supper. Not a particle of the clothing I brought with me have I been able to present myself in and the cost of a Lady’s dress is far more expensive and must be more diversified than that of a man. The number of servants which must be kept is at least treble of that which is necessary elsewhere and the climate of the country requires for every individual expenses of clothing unknown in more southern regions,” he wrote in February 1810.

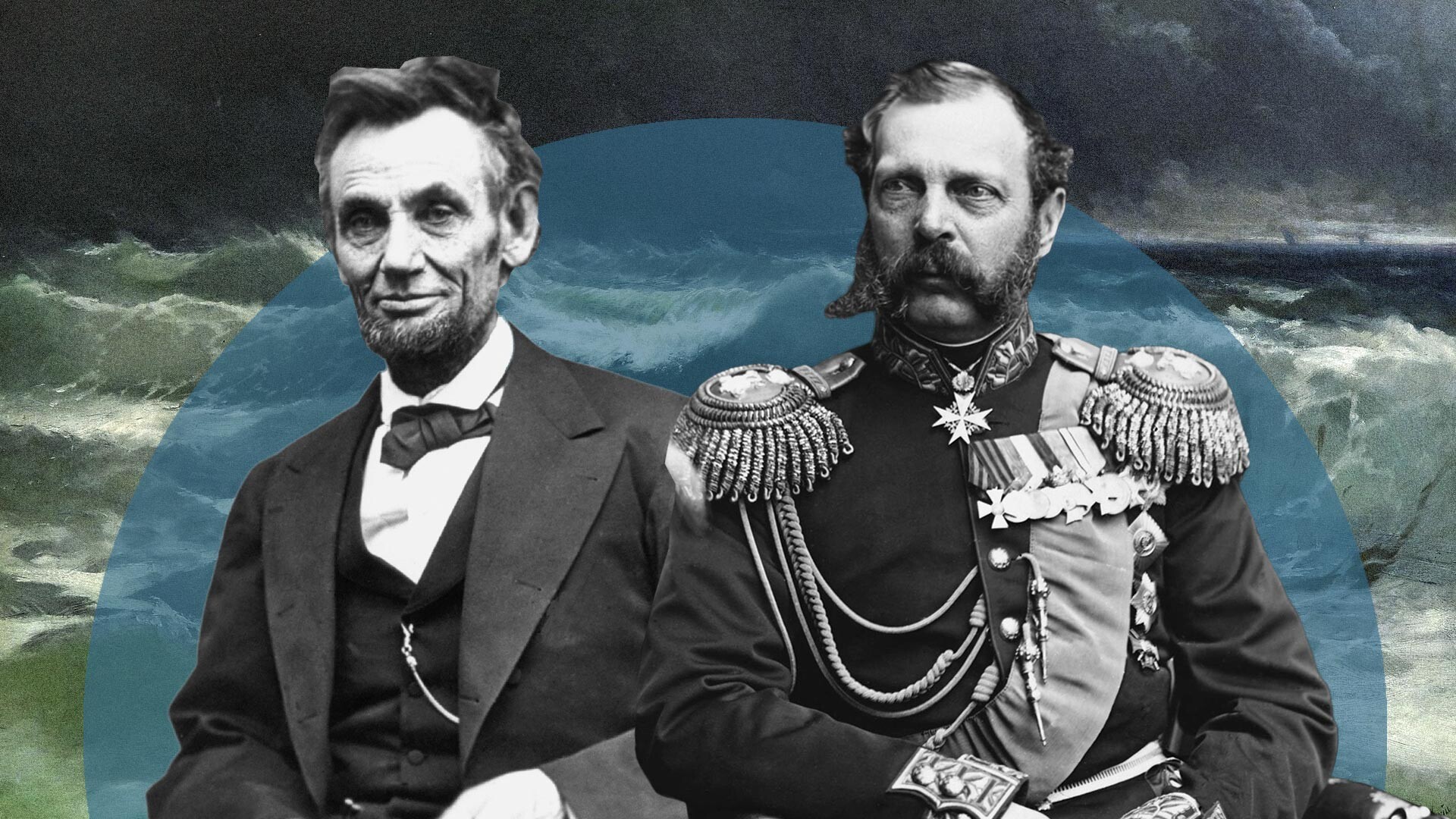

Adams worked in Russia until 1814. He served during the Napoleonic Wars and the diplomat’s task was to secure the greatest possible trade preferences for the United States. The difficulty was that the United States was at odds with England, then an ally of Russia. Nevertheless, Adams quickly built a good personal relationship with Emperor Alexander I. They even strolled together along the banks of the Neva River.

In 1811, John and his wife Louise had a daughter, Louise Catherine. Sadly, she died a year later and became the first U.S. citizen to be buried in Russia.

At the request of Noah Webster, the dictionary author, Adams sent him books on Russian grammar and vocabulary. This was the beginning of the study of the Russian language and culture in the United States.

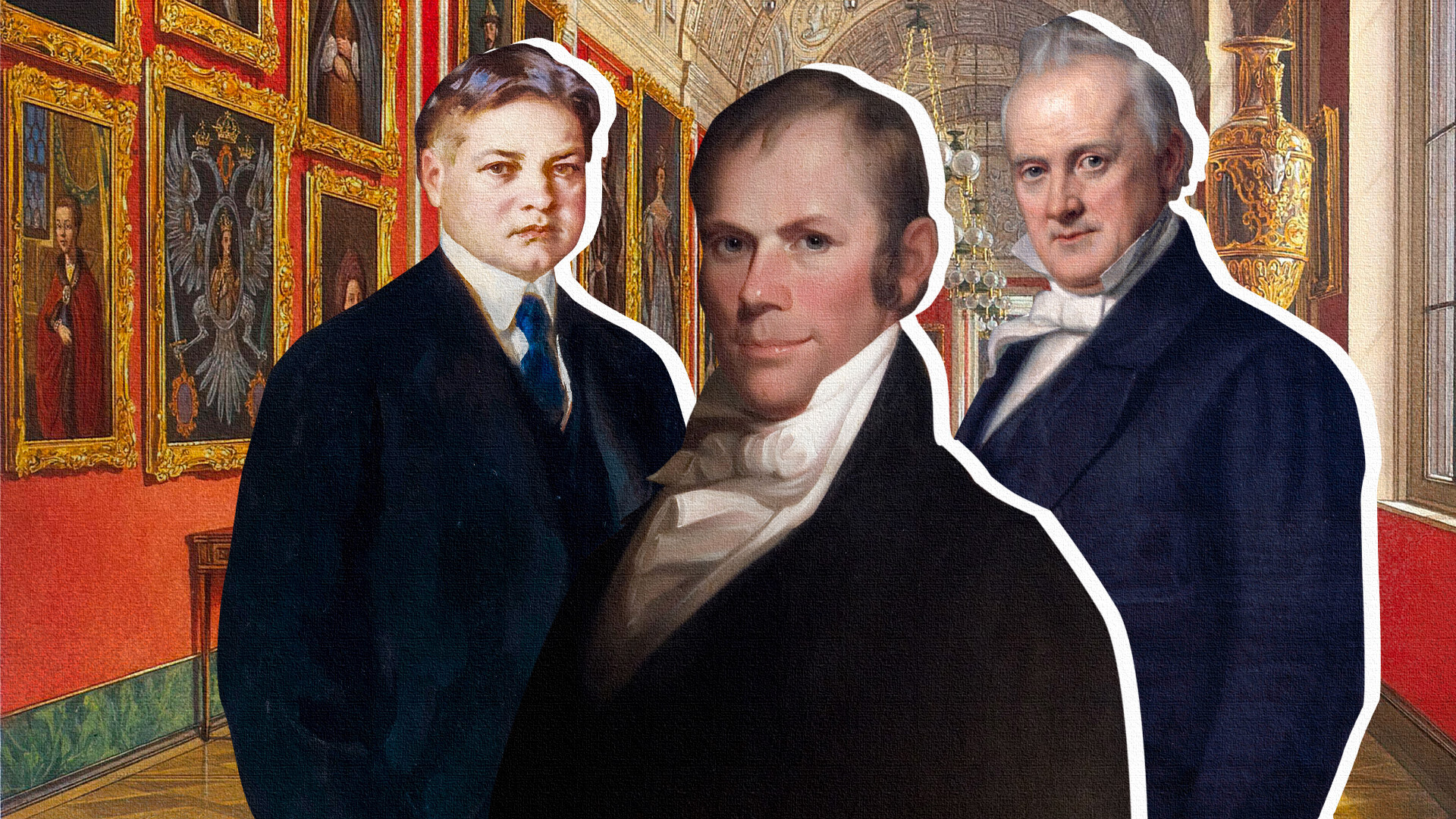

2. James Buchanan, the 15th president of the United States, worked in Russia from 1832 to 1834.

James Buchanan by George Peter Alexander Healy.

James Buchanan by George Peter Alexander Healy.

Thanks to James Buchanan, the Russo-American Treaty of Commerce and Navigation was signed in 1832. The document provided for common bilateral trade rights and established terms of most-favored-nation trade.

Despite his short tenure, Buchanan managed to establish connections in St. Petersburg and gain the favor of Emperor Nicholas I.

“The emperor is the ideal sovereign for Russia; and, from my point of view, he is a more capable and virtuous man than any of those who surround him. I flatter myself that a positive change has taken place in his attitude toward the United States since my arrival. Indeed, at first, I was treated with utter contempt. Whatever our opinion of his politics is, everyone here recognizes that, in private relations, his character sets an example for the whole empire. As husband, father, brother and friend, he is an example to his subjects,” he wrote to his sister.

When the diplomat left St. Petersburg, Nicholas I asked him to tell President Jackson that the new American envoy should be “like Buchanan”.

3. Herbert Clark Hoover, the 31st president of the United States, worked in Russia as an entrepreneur from 1909 to 1913 and helped during the mass famine of 1921-1923.

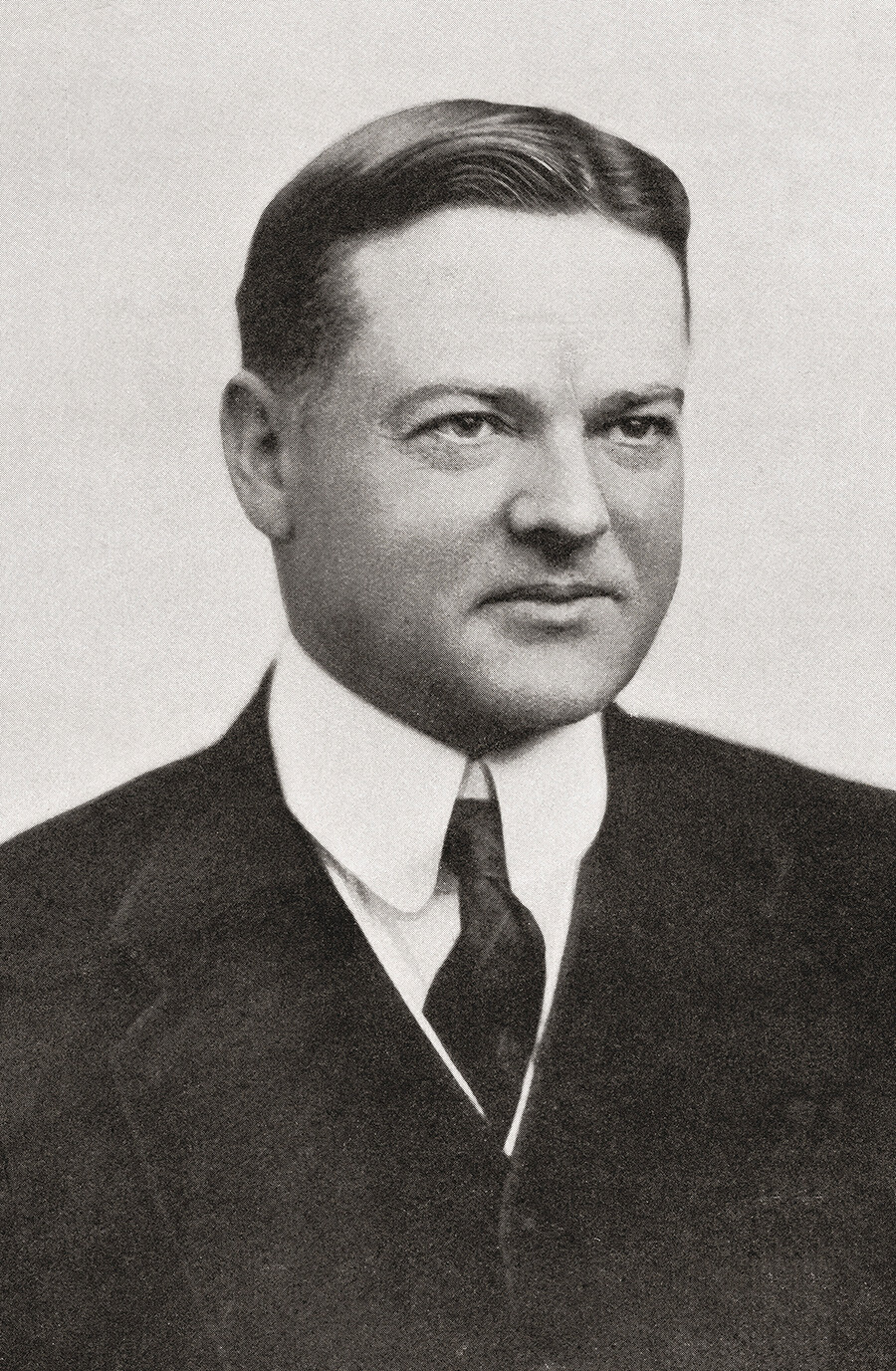

Herbert Clark Hoover, 1874 - 1964. 31St President Of The United States Of America. From The Year 1919 Illustrated.

Herbert Clark Hoover, 1874 - 1964. 31St President Of The United States Of America. From The Year 1919 Illustrated.

Herbert Clark Hoover, a mining engineer by profession, had been working in Russia since 1909. In Kyshtym in the Urals, he bought the enterprises from the heirs of the South Urals merchant Lev Rastorguev and created the joint-stock company ‘Kyshtym Mining Plants’. He was engaged in both financial reorganization and modernization of production.

This success at Kyshtym brought important repercussions. Russian industry had, hitherto, been often dominated by German and British operators. The Russians were always suspicious of them, fearing political implications. They resented the assumed superiority of the British and the German officials. They had none of that feeling toward Americans. The Russian engineers were most able technical men, but lacked training on the administrative side. There was instinctive camaraderie by which the Russians and Americans got along together,” Hoover wrote in his memoirs.

Hoover, who quickly gained prestige in Kyshtym, was later invited to supervise the development of the mining fields in the Altai Mountains. In his opinion, it was the largest and richest ore deposit known in the world. American engineers worked there until the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution.

Hoover left Russia in 1913.”"Had it not been for World War I, I would have had the largest engineering fees ever known to man,” he recalled of his work in Russia. He also headed several mining and oil companies.

In 1917, the United States severed diplomatic relations with the newly formed Bolshevik government. Nevertheless, when a mass famine broke out in Soviet Russia in 1921, Hoover, already Secretary of Commerce and head of the American Relief Administration (ARA), sent humanitarian supplies to the country, despite the fact that he was extremely negative about Bolshevism.

ARA donated aid to 20 million people in Soviet Russia. It provided food and shoes, agricultural machinery and seeds and opened hospitals and dispensaries.

Under President Hoover, the U.S. actively developed trade relations with the USSR. In 1932, with American assistance, an automobile plant in Nizhny Novgorod and a metallurgical plant in Novokuznetsk were launched.