How German settlers celebrated Christmas in the Russian Empire

Starting from the second half of the 18th century, Russia was flooded with foreigners who were invited by Empress Catherine the Great to populate and develop the vast lands of the empire. Among them were many peasants from the German principalities, namely from Baden, Württemberg, Hessen, Prussia, the Palatinate, Rhineland and Alsace.

Immigrants formed multiple colonies all across the Russian lands - from the south of the country to the Urals and Siberia. Having obtained a number of privileges from the Russian authorities and a comparatively high level of autonomy, the Germans strove to preserve their culture, religion, language, their cuisine and everyday traditions. They also cherished their national holidays and related customs.

Christmas was one of the biggest days of the year for the colonists. The traditions of celebrating it varied from community to community. The reason for this was the fact that immigrants from the German lands belonged to different Christian churches: among them were Catholics, Lutherans, Mennonites and Evangelists.

It’s now difficult to describe the full picture of their Christmas traditions in all their details and diversity. Not all settlements were described at length by social anthropologists before the 1917 Revolution; while afterwards, research into the culture of Russian Germans was hampered by the turbulence of the 20th century. What we do know is based on descriptions from a number of expeditions and memories of people who were born in the first half of the last century.

The German settlers celebrated Christmas on December 25, but the festivities started the day before, on the eve, and lasted for several days. It was considered unacceptable to work during holidays, and thus, Christmas Eve was traditionally spent in preparations: the colonists cleaned up their homes, cooked special dishes, and adorned their Christmas tree with handmade decorations and candies. People usually chose a fir-tree. However, in those regions where coniferous forests were rare, some other type of tree could be chosen. Social anthropologists point out that in the Volga Region, several weeks prior to the holiday, the Germans cultivated dogwood and lilac in water; they also planted barley and wheat seeds in boxes with soil to also use for decorating.

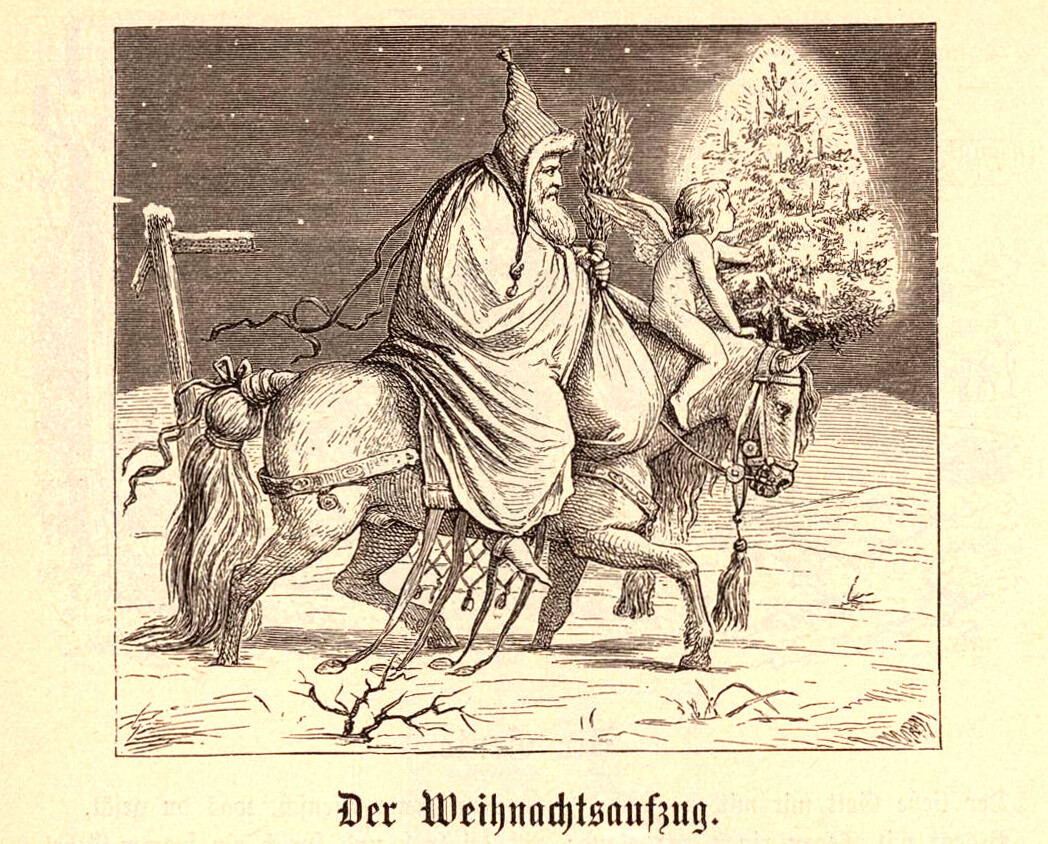

On Christmas eve in most regions children were visited by Pelznickel. This was a man donning a fur-coat, with the fur visible from the outside. He wore chains and disguised his face, holding a stick in his hands, or sometimes twigs and a bucket. When inside, he would move around on his hands and knees. Pelznickel could take naughty children from under their beds and frighten them with his brutal appearance, loud deep voice and the clamorous sound of his chains. To punish a child, he could make them chew on the chain, eat onions or garlic, and do other tasks.

His name could differ from settlement to settlement; for instance, he was known in the Volga Region as Weihnachtsfuchs, but in Volyn - as Pelzbock.

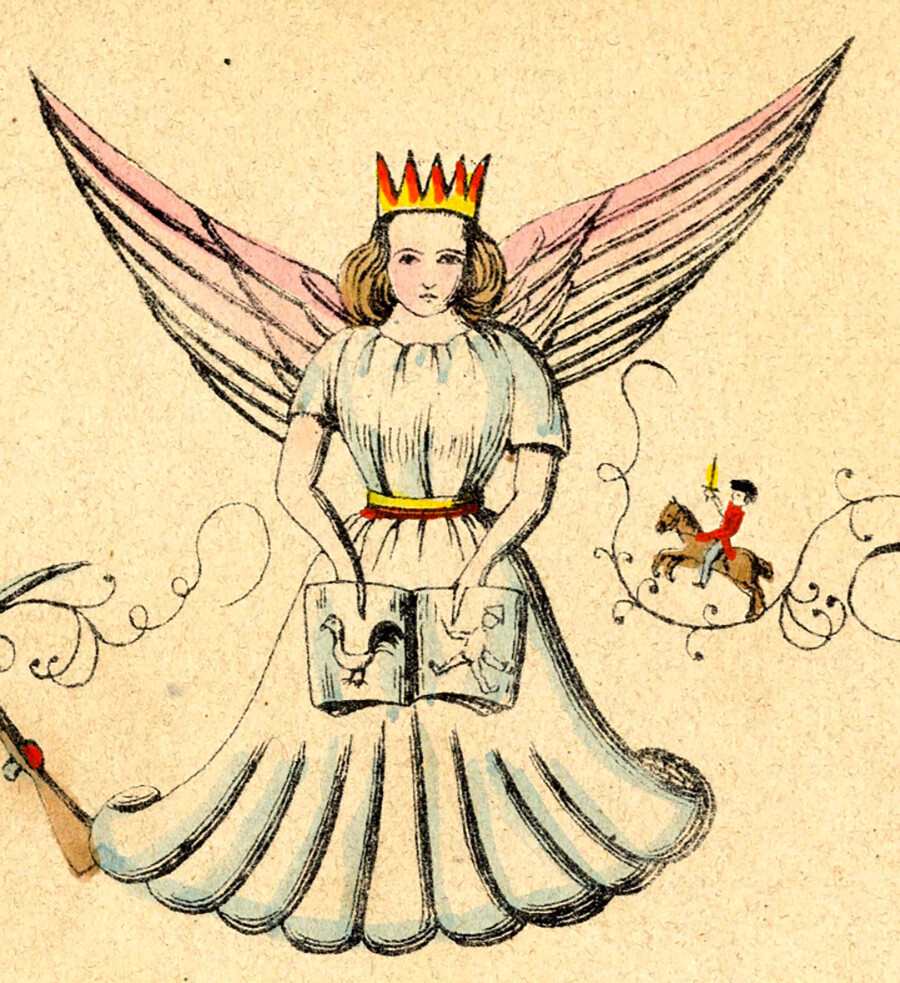

Together with Pelznickel, either before or after him, came Christkind. He could be played by a boy or a young man, but most often it was a girl who did. Christkind, who wore a white dress and hid his face underneath a veil, was a kind spirit, but could punish as well. Not only children had to fear him, but also overly nosy adults who attempted to peek under the veil. Sometimes, he and Pelznickel were accompanied by assistants and other fancy-dressed people. Children promised Christkind to behave themselves, said prayers and recited poems, receiving gifts and candy for this.

In the Volga Region, Christkind was at times met or seen off with the following words:

Christchen, komm,

Mach mich fromm,

Da ich dafür

In Himmel komm.

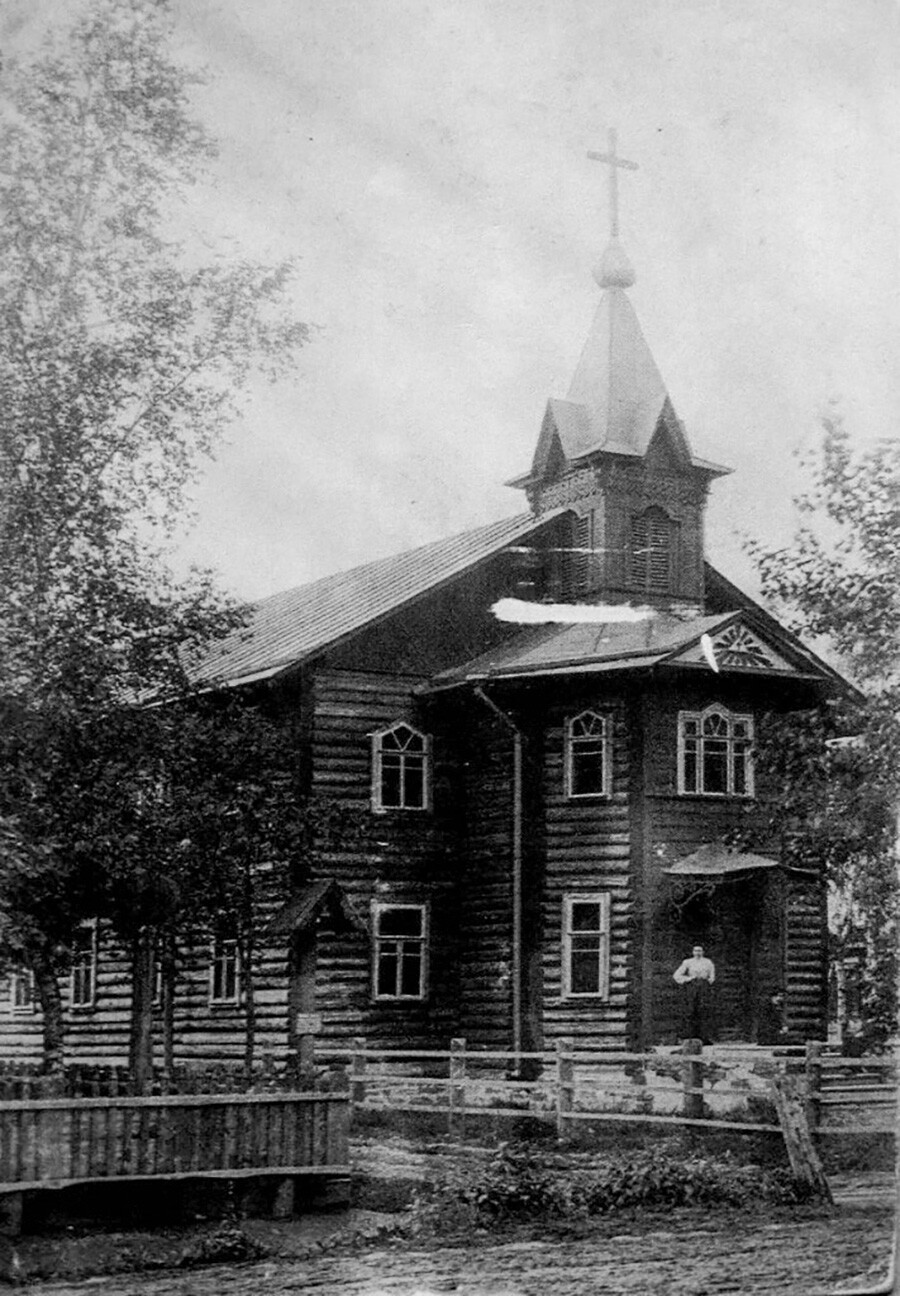

On the evening before, entire families would certainly go to church. A decorated tree also stood there, from which nice small surprises and candies were taken and given to children after the service.

St. Nicholas Lutheran Church in the German colony of Grazhdanka

St. Nicholas Lutheran Church in the German colony of Grazhdanka

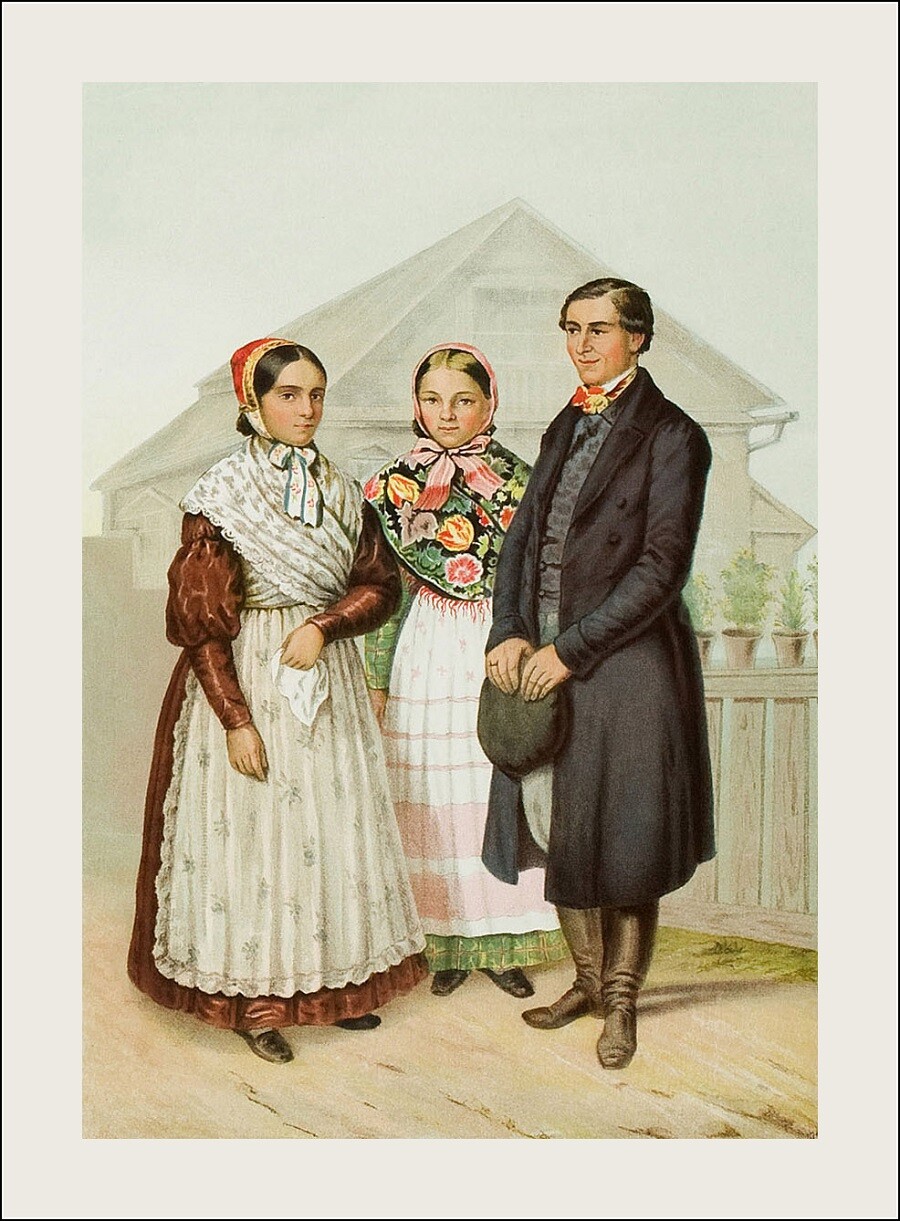

One had to dress up to go there: women would typically wear blue overskirts and woven woolen underskirts, sleeveless jackets, white blouses and floral-patterned aprons, as well as beads. Men would freshen up their outfit with colorful scarves, ties and chained watches, putting on waistcoats, caftans or short jackets called Binschak over their shirts.

At home, the Germans would have a festive dinner and distribute gifts: in some families, in St. Petersburg for instance, they could be “pre-ordered” well in advance if somebody wanted to.

The festive menu varied in different regions of the empire. According to some researchers, the Volga Germans didn’t serve meat on Christmas: it was considered to potentially lead to their cattle being attacked by wolves.

Thus, on the first day of celebrations a sweet soup (Schnitzsuppe) was cooked, with poultry roasted on the second day. In Siberia, there was always a goose on the Christmas table, which was cooked using a special recipe. In the southern colonies, it was quite the opposite, pork was eaten “to bring happiness”, served together with sour cabbage that was expected to bring health to the household in the new year. The colonists also liked dumplings and pastry of all kinds.

Adults would enjoy themselves till morning, drinking wine or vodka. Youngsters in some settlements would go from house to house, wishing their neighbors a Merry Christmas, and would gather in the street or celebrate separately from adults, in their own circle. This was all accompanied with songs and dances, some of which, for example the seven-knee ‘Augustin’ (Siebentersprung), or the hop-waltz, had been brought by the colonists’ ancestors from their German homeland; whereas others, for instance the famed Kamarinskaia, was eventually borrowed from the local Russian population. Their favorite Christmas song was “O Tannenbaum, o Tannenbaum”.

Evangelists, Baptists and Mennonites celebrated Christmas in a more reserved and unpretentious manner. In their settlements, the festivities typically boiled down to saying prayers and giving presents, while their children were visited by Weihnachtsmann instead of Pelznickel. On the eve, the Mennonites would gather at their preacher’s place, where they took part in the solemn ritual of foot washing.

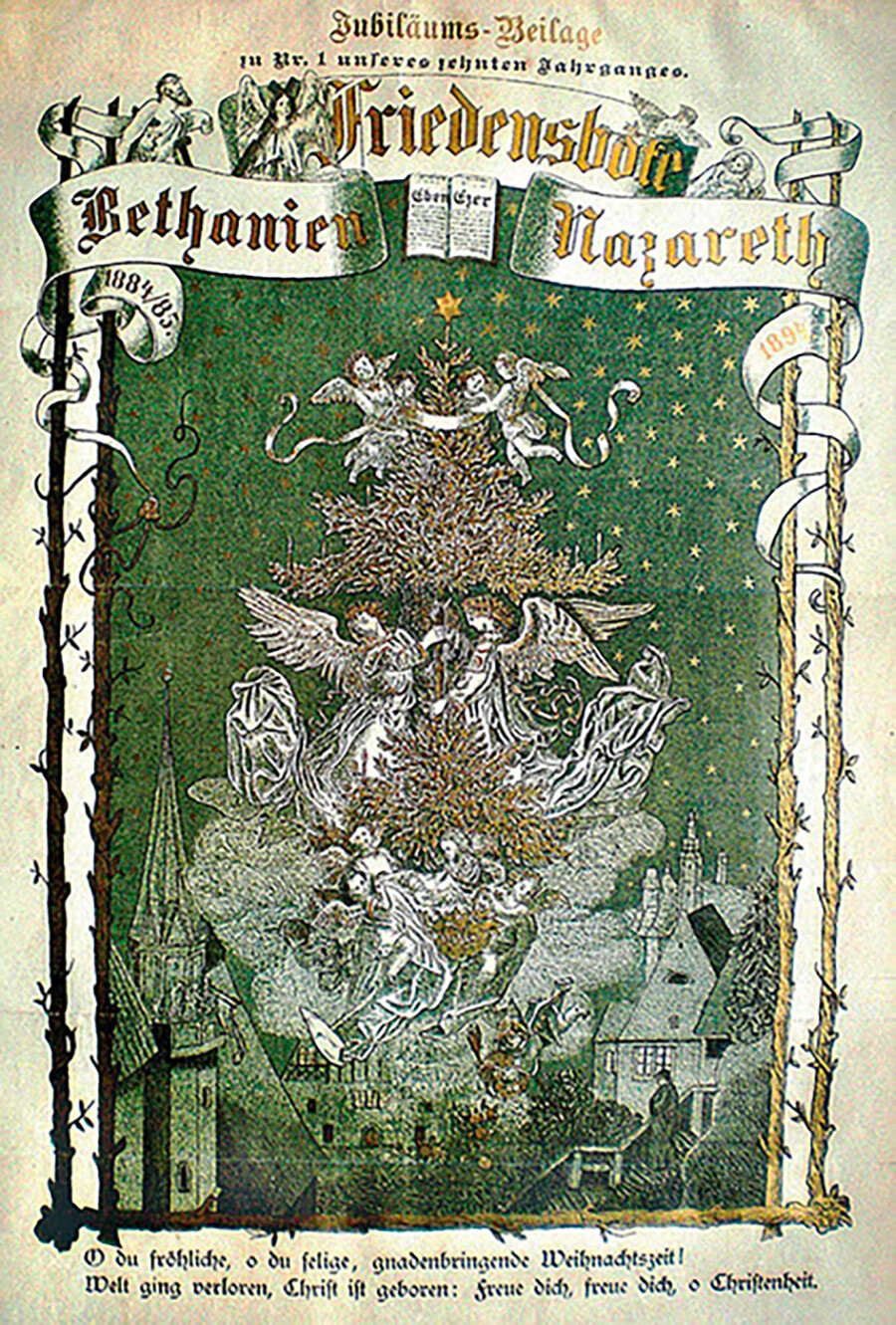

'Friedensbote' magazine of German settlers

'Friedensbote' magazine of German settlers

In the Volga Region, quite often weddings, which were especially popular in winter time, were slated for the second day of festivities. The Christmas week, which spanned from December 25 until December 31, was a period of calm before Silvesterabend, the New Year’s Eve. The Siberian colonists took this time to pay special attention to their behavior, praying a lot and trying not to use swear words. The locals could also use the opportunity to predict the weather in the forthcoming year, having salted an onion and analyzing the way it looked.

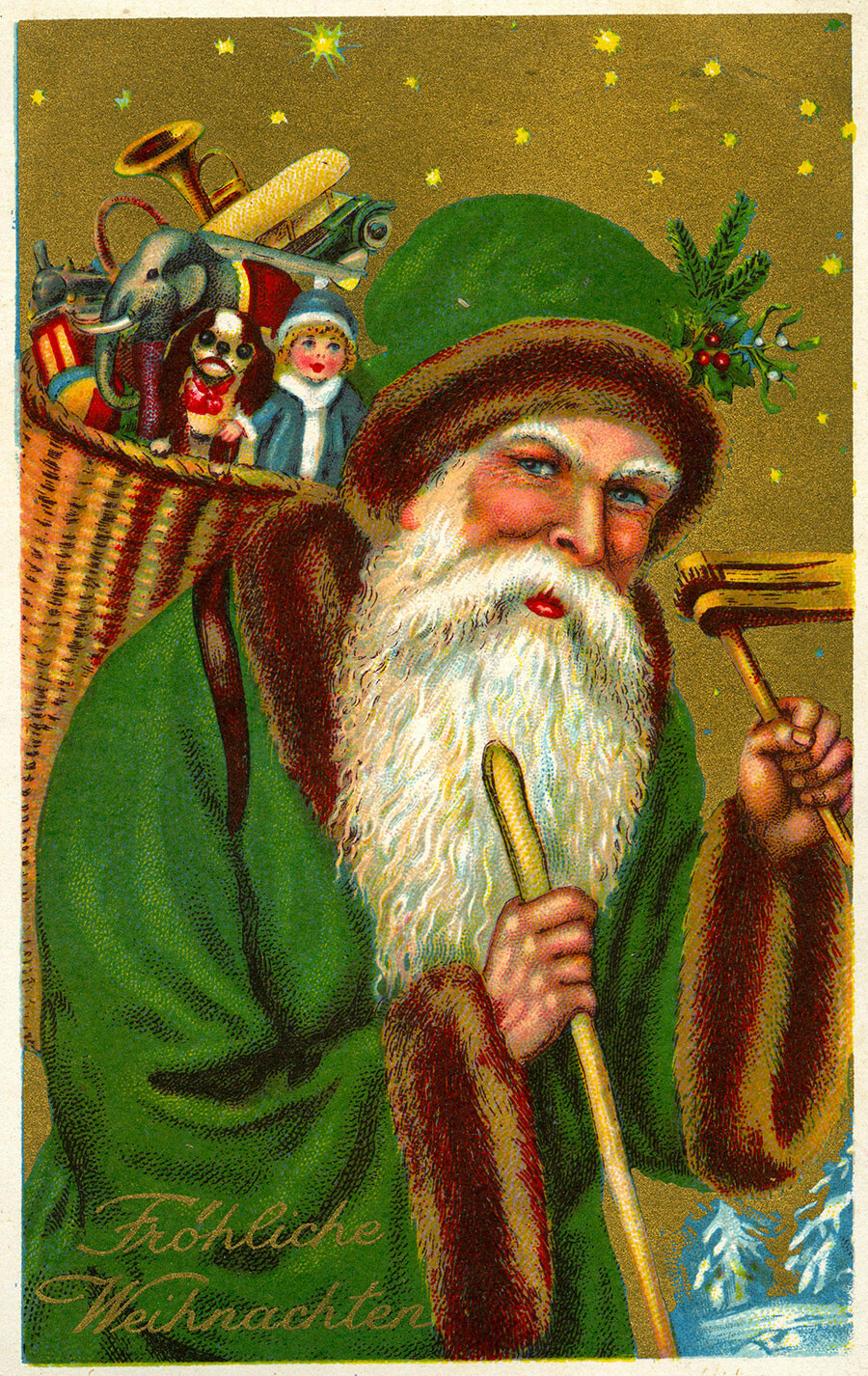

Frohliche Weihnachten - Merry Christmas

Frohliche Weihnachten - Merry Christmas