What the Romanovs gifted each other for Christmas

Today, Russia’s main holiday that’s associated with the evergreen tree and gifts is not Christmas, but rather, New Year’s. The atheist Soviet state is responsible for this, because it abolished the celebration of Christianity’s Christmas and instead gave the people a secular national celebration on New Year’s Eve.

Before the Revolution, Russians loved and eagerly celebrated Christmas. While now the Orthodox Church celebrates Christmas on January 7, until 1918 it was celebrated, just as all other Christians do, on December 25. This day of course was special for the tsar’s family. No expense was spared to buy gifts for children and other family members.

Presents for children

In the 16th-17th centuries, the tsars attached great importance to Christmas but the celebration didn’t have a special family aspect. On Christmas Eve, the tsars made charitable acts – giving alms to hospitals and poorhouses, visiting prisons and even pardoning convicts. The tsars were certainly in attendance during the night service at church, which was the main event.

After services, closer to morning, Church leaders were invited to the royal chambers in the Kremlin, as well as the choir that sang special songs to the glory of Christ and the tsar. Those assembled enjoyed a holiday drink – “mead” – and were presented with ornate jeweled bowls.

Only afterwards did the tsar’s children receive their gifts, for example, embroidered expensive cloth (silk and brocade) and precious cups with gems. The tsareviches were given toy sabers, while the tsarevnas received various pieces of jewelry.

Until the 19th century, holiday gifts were common only among rich and noble families.

First gifts under a Christmas tree

For a long while it was not a tradition in Russia to decorate a Christmas tree, because such trees (firs) were usually associated with the dead. Fir branches were strewn on the road to the cemetery during a funeral procession, symbolically showing the way for the deceased’s soul.

Peter the Great was the first to order homes to be decorated with Christmas trees when in 1700 he introduced the celebration of New Year’s. German-born Catherine the Great also supported the New Year’s tradition.

A Christmas tree was first decorated in the Kremlin in 1817. From the 1820s onward, this tradition spread to the tsars’ palaces in St. Petersburg. During the reign of Nicholas I gifts were hidden under the Christmas tree. It’s believed that a family Christmas celebration with a tree was introduced to the imperial court by the emperor’s wife, Alexandra Feodorovna. She was German-born, the daughter of Prussian King Frederick William III, and their family had always celebrated Christmas on a grand scale – with a magnificent Christmas tree and gifts.

Nicholas I’s wife, Alexandra Feodorovna

Nicholas I’s wife, Alexandra Feodorovna

“During the reign of Emperor Nicholas I, Christmas among the aristocracy, and later among townsfolk, acquired the traits of a home family celebration that people prepared for carefully, sparing neither time nor expenses,” Yulia Uvarova states in her book Christmas and New Year’s in 17th-20th Century Russia.

Sometimes, there were so many gifts that they didn’t all fit under the tree. In 1847, Nicholas’ son, Grand Duke Konstantin, listed in his diary all the numerous gifts that he received: a saber, a dagger, a chainmail, Circassian pistols and books.

The view of the Rotunda of the Winter Palace where a Christmas tree was installed

The view of the Rotunda of the Winter Palace where a Christmas tree was installed

Nicholas I’s daughter, Olga, remembered that in 1837 she received a writing desk with a chair, and in 1843 she received “a beautiful Wirth piano, paintings, elegant dresses, and from my papa – a bracelet with a sapphire – his favorite precious stone.”

One of the most popular stores from where the emperor ordered gifts was the “English store” in St. Petersburg that belonged to the firm Nicholls & Plinke, which sold exquisite chandeliers and jewelry, as well as expensive beautiful weapons, excellent wines and many other fine items.

In 1839, this tea set from that store was a Christmas present for Maria, another of Nicholas’ daughters. In 1850, the emperor gifted her a furniture set – luxurious couches, armchairs and console tables.

Tea-and-coffee set by Nicholls & Plinke, 1839

Tea-and-coffee set by Nicholls & Plinke, 1839

In addition to paintings, jewelry, beautiful dresses and trinkets (like clocks with surprises) the princesses also received various items that they could actually use – ice skates, skis, sleds, and books.

The children could also make a wish-list and request something particular for a gift. For example, Alexander III’s brother, Vladimir, when he was a kid, asked for oysters for Christmas because he really enjoyed eating them. Tsesarevich Alexander himself was also quite original – he asked for a toy kitchen and a chimney sweeper costume.

In 1883, Alexander III ordered the Imperial Porcelain Factory to manufacture the ceremonial Raphael Service for 50 persons – the work took 20 years and every year the factory sent a part of the fulfilled commission just before Christmas.

A plate, a caviar dish and a saucer from the Raphael Service

A plate, a caviar dish and a saucer from the Raphael Service

Military gifts for men

Military items were a traditional present for royal men. It’s known that the empress in various years gifted the heir to the throne, Grand Duke Alexander (future Alexander III), a Chevalier Guard Regiment uniform, a Turkish saber and porcelain plates depicting different types and kinds of Russian troops. However, she also gave him a tea set. From his father, the emperor, Alexander received, for example, a box with pistols, a Peter the Great bust, and Russian history books.

This scimitar with a scabbard, made in the Ottoman Empire in 1803, was presented to the future emperor Alexander II by his wife, Maria Alexandrovna, on Christmas 1849.

Scimitar with scabbard. Turkey. 1803

Scimitar with scabbard. Turkey. 1803

It’s known that in 1881 Emperor Alexander III received a Smith & Wesson revolver with ammunition and a holster from his wife.

Sweets were usually only given to children, but adults could also receive treats as a gift – for example, a crate of expensive prunes or dried apricots, as well as mandarins.

A watercolor painting by Grand Duchess Olga, the daughter of Emperor Alexander III

A watercolor painting by Grand Duchess Olga, the daughter of Emperor Alexander III

A lottery for the courtiers

During Christmas, the imperial family always held a lottery with gifts for the courtiers. Porcelain lamps, vases, tea sets and even works of Fabergé were given away. The royal children also helped arrange such lotteries – before it started they spent hours putting labels with numbers on the gifts.

The members of the imperial family also gave presents to their entire staff and other personnel in the palace. They also didn’t spare any expense for this. A governor could receive an expensive box or silverware; they also were given pearls and other ‘trinkets’.

The last Christmas of Nicholas II

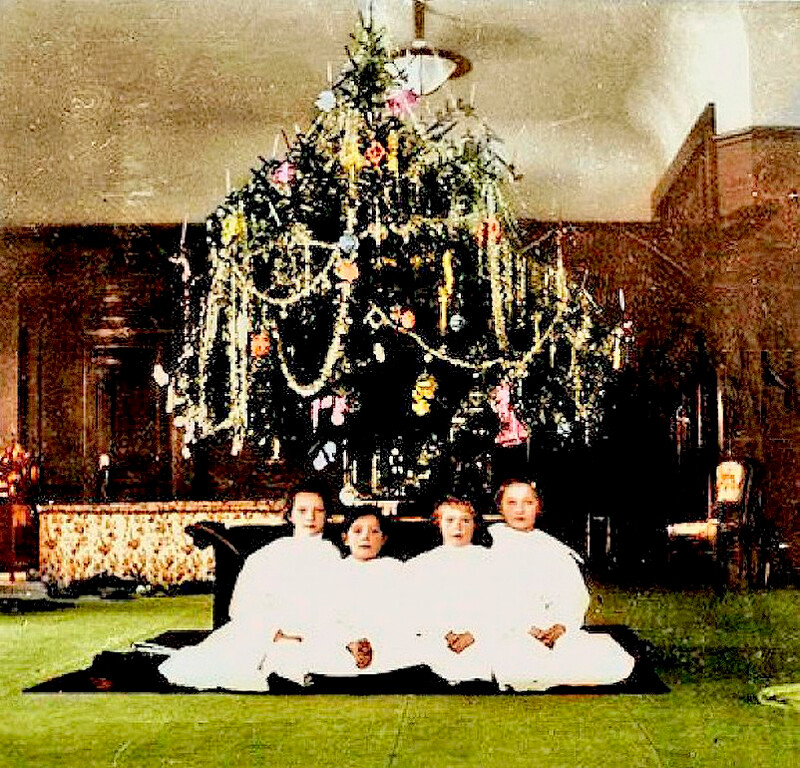

A Christmas tree for the children of the tsar’s servants

A Christmas tree for the children of the tsar’s servants

Nicholas II celebrated Christmas quite modestly. Especially when, at the beginning of the 20th century, the country saw hard times – revolutions and wars.

In the palace in Tsarskoye Selo, where the imperial family lived, three Christmas trees were decorated – there was one in the big hall, a separate one for children, and finally, one for the servants. Nicholas II jotted down his impressions about Christmas in his diary. He wrote that after noisy and crowded celebrations where gifts were handed out over the course of several hours, they also had a more intimate Christmas gathering. “Then Alix and I had a celebration just for the two of us.”

Nicholas II with his wife and children

Nicholas II with his wife and children

While Nicholas gave his wife an expensive jeweled egg by Fabergé every Easter, he gave more modest presents for Christmas. For example, he gifted the empress jewelry only twice – a diamond necklace the year when they were married, and jade pendants for Christmas after the birth of their first child – Princess Olga.

Russia’s last royal couple also gave modest gifts to their kids. For example, the heir, Alexey, received his first diary from his mother the empress.

For Christmas 1917, during their Siberian exile, Empress Alexandra herself knitted woolen vests for the children. To her lady-in-waiting and friend Anna Vyrubova the empress sent a package with a scarf and stockings that she had knitted (she also put flour, pasta and sausage in the package – items that were a true luxury in post-Revolutionary Russia).