The U.S. launched HUNDREDS of SPY BALLOONS against the Soviets during the Cold War

The U.S. Air Force launched the program of high-altitude spy balloons soon after World War II. Despite numerous complications, the spy balloons proved to be an economical and effective way to gather intelligence on the Soviet Union, paving the way for the use of high-altitude spy planes that caused a diplomatic scandal in 1960.

Spy balloons

By the 1950s, when Cold War tensions with the Soviet Union crystallized, the U.S. required a reconnaissance tool to watch its enemy undetected.

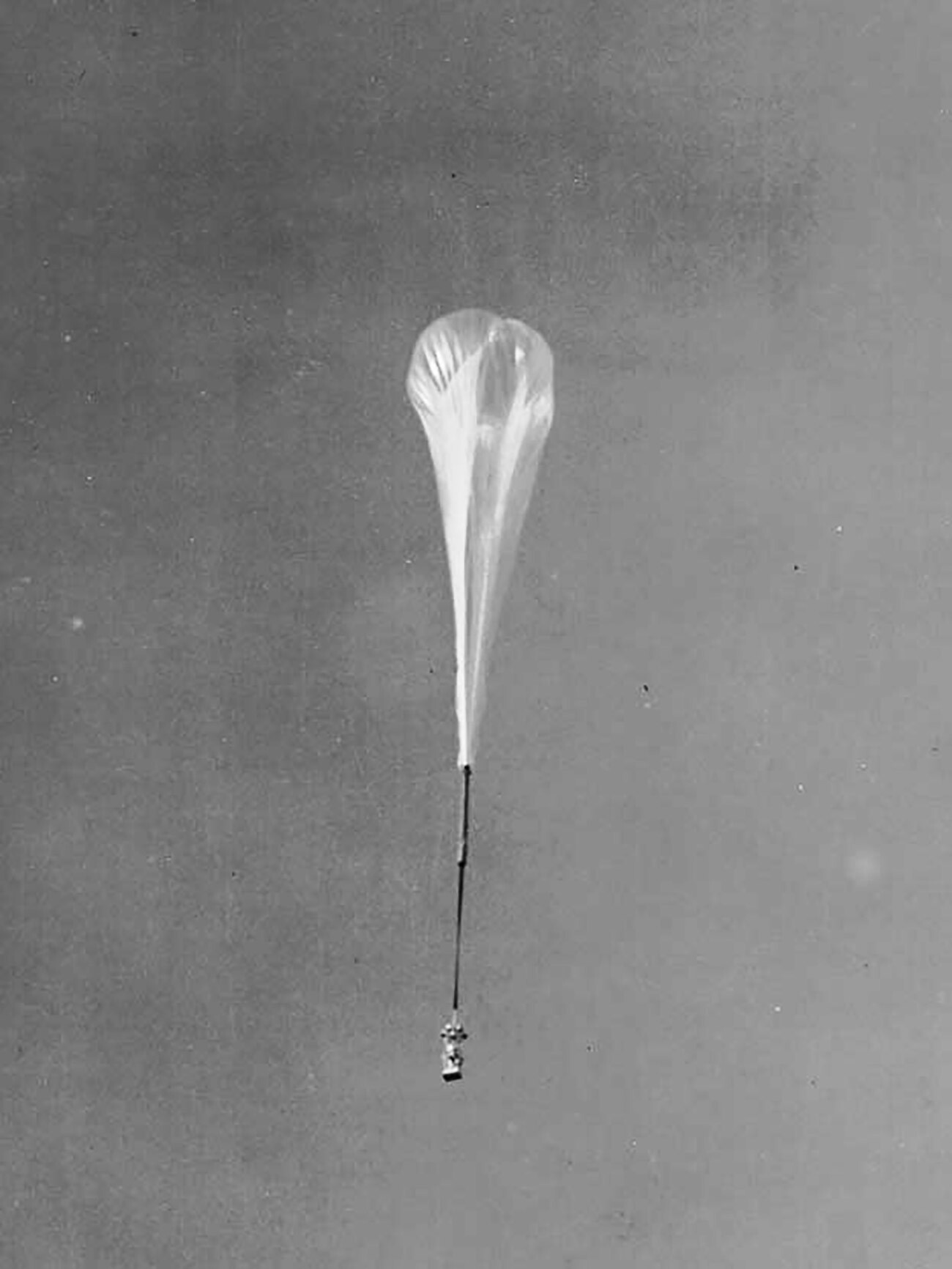

Upon discovering that jet streams of high-altitude generally meander from west to east, the U.S. Air Force concluded that high-altitude balloons released from Western Europe would hypothetically fly to the east, meaning that they would most probably fly over the USSR and then reach U.S. military bases in Japan where it would be possible to collect the data.

If so, the U.S. spy balloons would be able to gather valuable intelligence about the USSR’s military, especially about the country’s nuclear capabilities, and – most importantly – stay out of reach of the Soviet air defense by cruising at 15,000 meters (50,000 feet) above sea level.

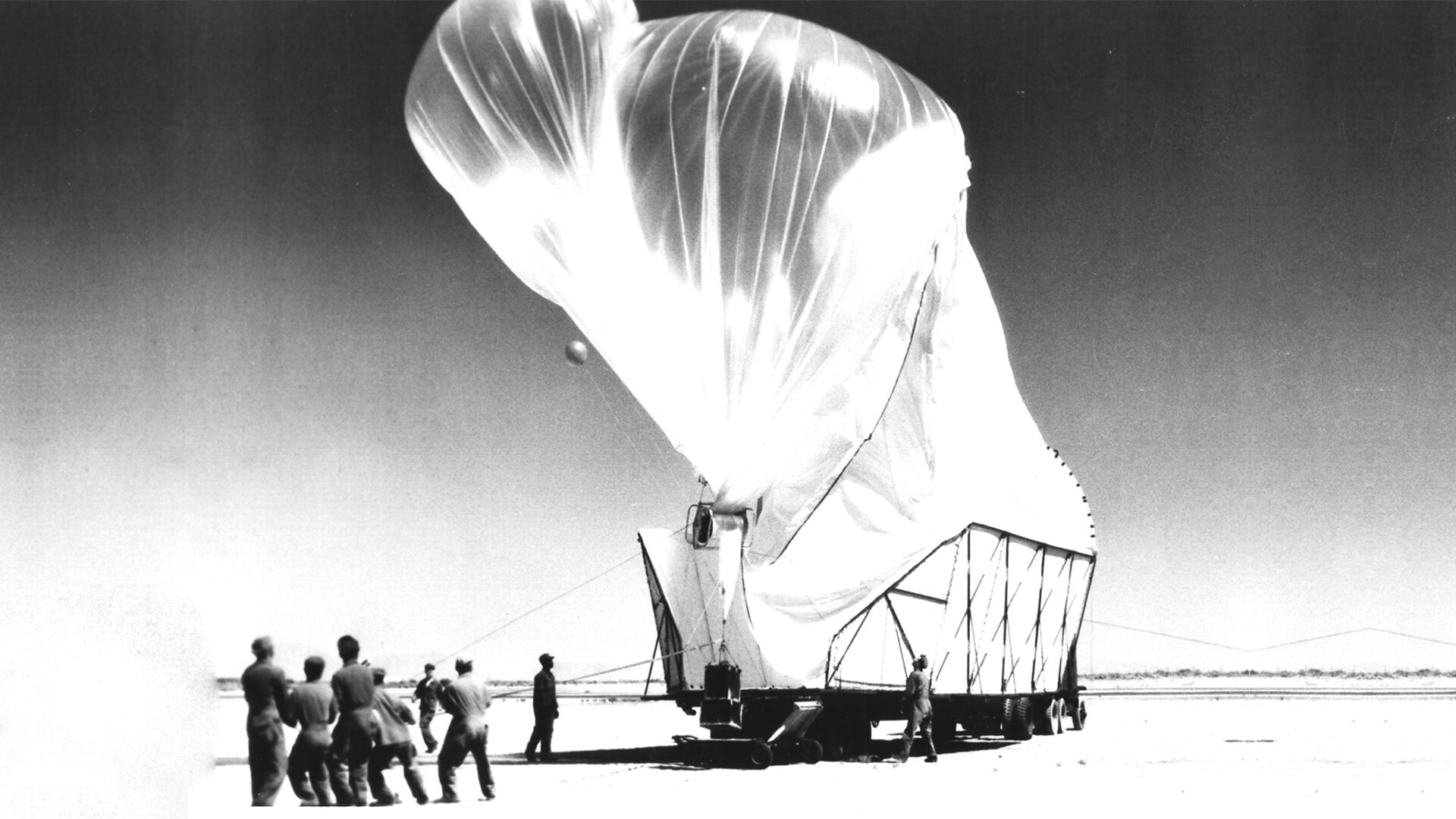

Skyhook balloon leaving the deck of the USS Norton Sound (AVM-1) on March 31, 1949.

Skyhook balloon leaving the deck of the USS Norton Sound (AVM-1) on March 31, 1949.

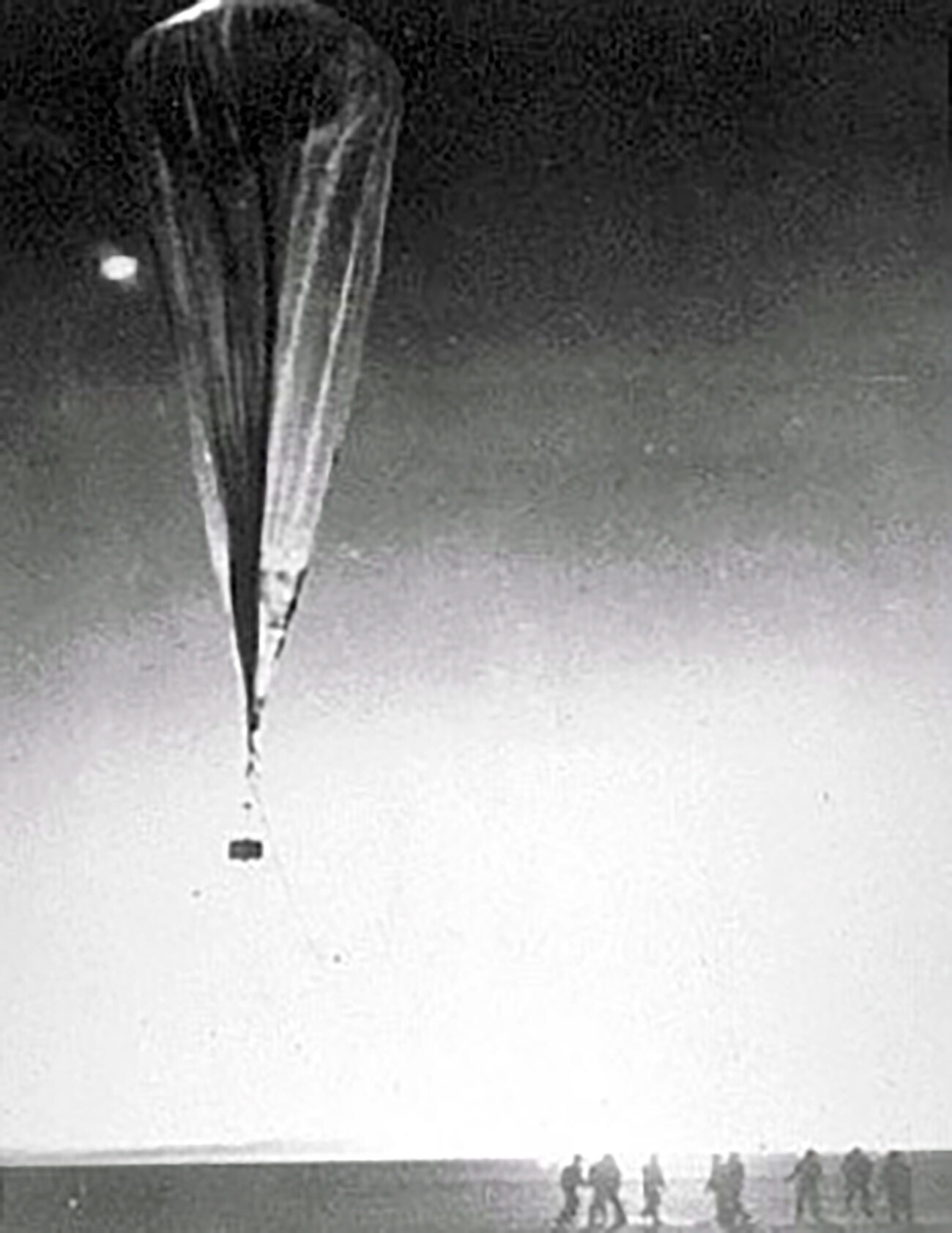

On January 10, 1956, the U.S. military launched eight spy balloons from the territory of Turkey and one from the territory of West Germany. In the following weeks, the number of successful launches grew to a whopping 448 spy balloons heading east.

The appearance of hundreds of spy balloons in Soviet airspace did not go unnoticed by the country’s leadership. On February 4, 1956, the USSR issued a formal protest note to the U.S. through diplomatic channels accusing the U.S. of violating Soviet airspace and sovereignty. In the meantime, the Soviet military pondered ways to neutralize the threat.

Soon, Soviet MiG pilots discovered that the spy balloons dropped in altitude at night, descending into their strike zone. This basic discovery proved extremely effective: an estimated 90 percent of the U.S. fly balloons were either shot down by the Soviets or crashed in unidentified locations before being able to exit the vast territory of the USSR.

Nonetheless, the fraction of the remaining spy balloons that survived all the perils and reached the U.S. military bases carried invaluable information about roughly a million square miles of Sino-Soviet territory.

However, as the Cold War tensions grew, so did technologies used by the U.S. to provide a glimpse behind the Iron Curtain.

The U-2 incident

By the late 1950s, the U.S. switched from spy balloons to a more advanced and reliable spying tool: high-altitude reconnaissance and surveillance aircraft U-2.

The U-2 airplane similar to the one piloted by Gary Frances Powers in 1960.

The U-2 airplane similar to the one piloted by Gary Frances Powers in 1960.

In 1956, the U.S. started secretly sending U-2 airplanes over Soviet territory for reconnaissance missions. It was correctly assumed that the Soviets lacked the capabilities to shoot these planes down at the altitude of 21,000 meters (70,000 feet). However, President Eisenhower insisted on personally authorizing each flight, because it was impossible to anticipate a Soviet response.

The Soviet military detected the airplanes, but failed to reach them with existing surface-to-air missiles. Interestingly, Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev did not accuse the U.S. publicly, because such a protest would reveal the Soviet military’s incapacity to shoot down high-altitude airplanes.

S-75 surface-to-air missile system.

S-75 surface-to-air missile system.

On May 1, 1960 – two weeks before President Eisenhower was set to meet the Soviet leader Khrushchev in Paris – the White House authorized yet another U-2 flight over the Soviet territory. For Americans, this flight resulted in a debacle.

Wreckage of the American U-2 spy plane shot down over Sverdlovsk on May 1, 1960.

Wreckage of the American U-2 spy plane shot down over Sverdlovsk on May 1, 1960.

A missile launched by a newly deployed Soviet air defense system hit the U-2 aircraft. The airplane crashed and the American pilot, Francis Gary Powers, was captured by the Soviets.

The U-2 incident resulted in the cancellation of the upcoming Paris summit and shattered emerging, albeit premature, hopes for a peaceful resolution to the Cold War.

The Pilot Francis Gary Powers judged by the Soviet court for espionage in 1960.

The Pilot Francis Gary Powers judged by the Soviet court for espionage in 1960.

Interestingly, the U.S. spy balloon program benefited the Soviets in an unusual way. While examining the crashed balloons, the Soviet scientists discovered that the U.S.-made film used in the cameras was able to withstand the impact of high temperatures and exposure to radiation. This made it a perfect tool for the Soviets to use to record the far side of the moon in 1959.