Unusual traditions of the peoples of Russia related to love & sex

Up until the 20th century, a number of vestiges of local magical cults remained in the lives of some indigenous peoples of Russia.

Chukchis’ wife exchange

The Chukchi called this tradition “nevtumgyt” – something that ethnologists have translated as “partnership by wife”. Men entered into a friendship agreement, whereby each had the right to the wife of the other and such an alliance could include more than 10 couples at a time. Each man could take his friend’s wife for a few months and then return her to him. But, it also happened that a man would keep another man’s wife forever. The children born in such marriages were also considered to be common and the men were regarded as brothers. At the same time, such relationships were forbidden between real relatives, all the way to second cousins.

Chukchis next to their house.

Chukchis next to their house.

The 1924 newspaper ‘Polar Star’ published expeditionary materials of explorer Mikhail Kulikov from Chukotka and one of the interviews made it clear that the women generally viewed this tradition as positive. “It is always more fun to ride on fresh reindeer,” one of the local women told the ethnographer to the sounds of the other villagers’ laughter. In addition to a “friendly” marriage, which was formalized according to all the rules, exactly like the first one, a Chukcha could offer his wife to a guest – and he himself would leave the house for a while.

The tradition emerged, due the harsh living conditions in the Far North – a group marriage in part guaranteed the birth of offspring and genetic diversity, thus increasing the people’s survival rate. In addition, in the event of the breadwinner’s death, his wife and children were not left alone, as more than one family viewed the children as theirs.

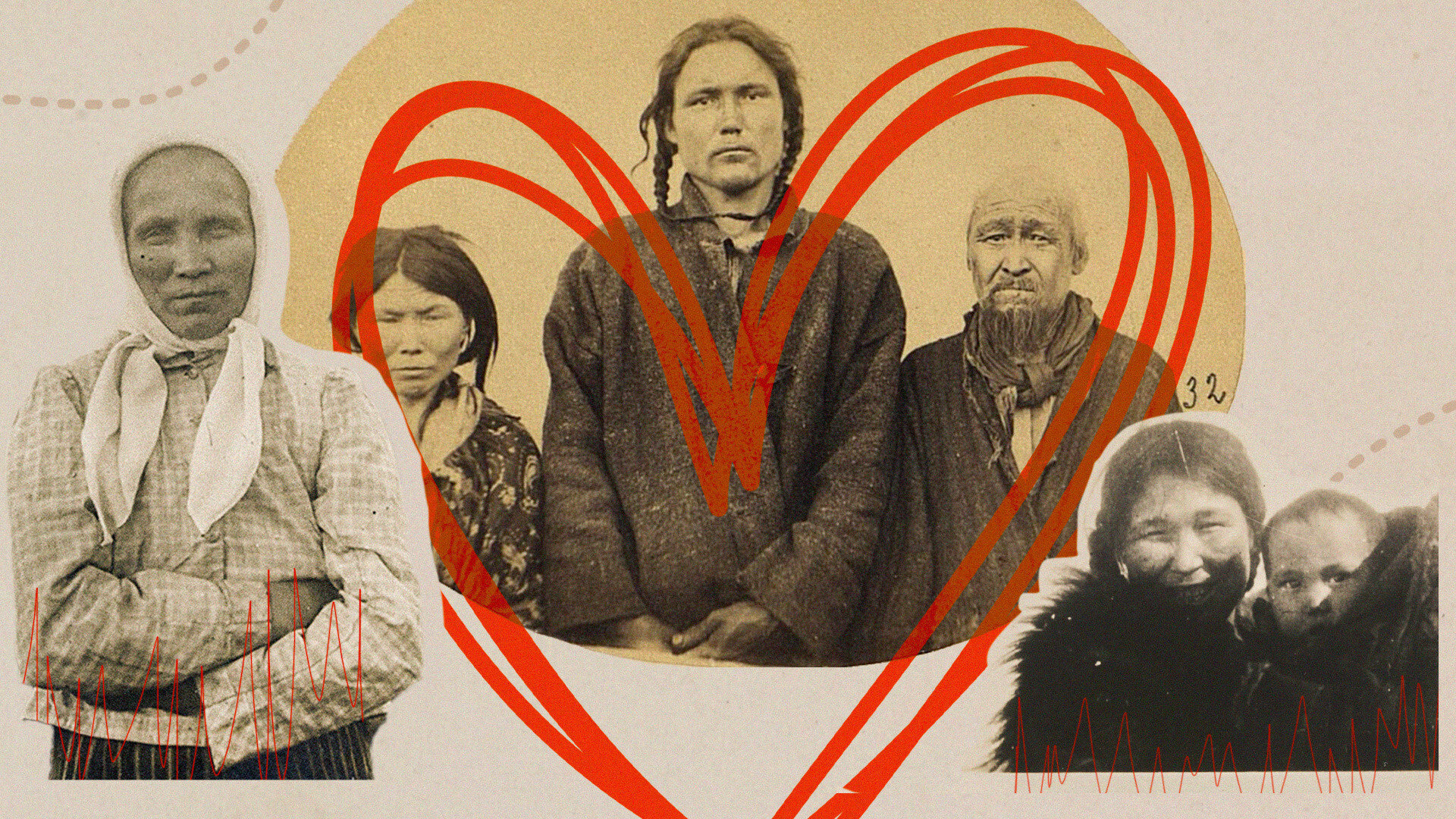

A portrait of a female chukcha, 1878 - 1880.

A portrait of a female chukcha, 1878 - 1880.

The Khanty’s hiding of the son- and mother-in-laws

This tradition was called ‘concealment’ or ‘avoidance’ and was observed not only by the mother-in-law in relation to her son-in-law, but also by the bride before the groom’s older male relatives. When a girl was betrothed, she began to appear in public with a kerchief and covered her face and also met several unusual requirements: she would constantly walk in front of the elder men of the bridegroom’s family wearing shoes, as it was forbidden to walk barefoot; in the presence of the would-be husband’s father and grandfather, she would “hide her voice”, that is merely whisper. The mother-in-law also “avoided” her son-in-law and, sometimes, it took unexpected forms: Soviet ethnographer Zoya Sokolova described a case when, in the presence of her son-in-law, a mother-in-law, not wearing a headscarf, covered herself with the hem of her skirt, although she was not wearing any underwear.

A family of Khants, 1916.

A family of Khants, 1916.

The compulsory covering of the head was explained by the fact that the Khanty people believed that a woman’s head was one of her four souls that had to be covered. Another three were in the shoulders, abdomen and legs. Meanwhile, breastfeeding in public was in no way condemned – breasts were perceived as merely an organ that contributed to reproduction.

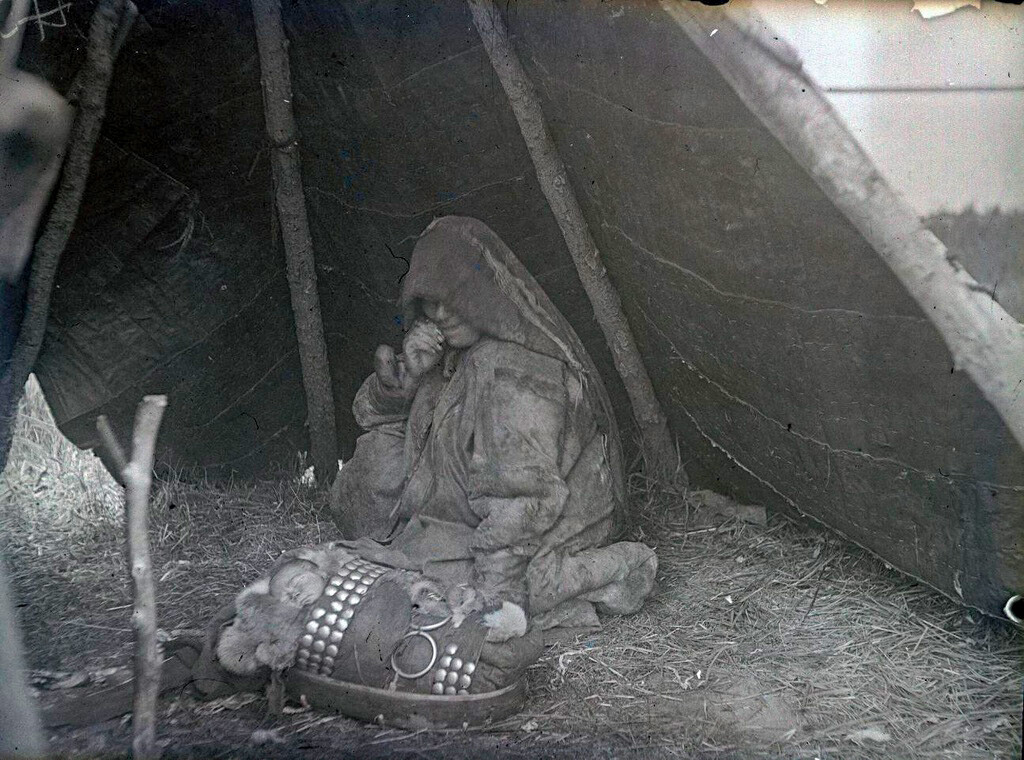

A Khant woman after childbirth in the special chum for newly-born children and their mothers, 1936.

A Khant woman after childbirth in the special chum for newly-born children and their mothers, 1936.

The Karelians’ ‘lembi’ magic

Karelians once had a pagan cult of ‘lembi’, but, later, the word began to be used to refer to women’s attractiveness, honor and beauty. It was believed that ‘lembi’ could be passed on to other women, so during the bride’s wedding bath, her friends and sisters bathed together with her. They used the same water and the same broom as the bride and then they wove their ribbons into her plait – part of the bride’s charm was, thus, passed on to them.

Also, to strengthen the spouses’ love, the groom would be served a cake, with dough for it having been kneaded with water or milk used to wash the bride at the wedding or post-wedding bath. Such traditional magic was typical of Karelians up until the early 20th century.

Karelian women, 1915.

Karelian women, 1915.