Why was the war against Finland so difficult for the USSR?

On March 12, 1940, the Soviet-Finnish War, known as the Winter War, ended. As a result, the USSR had generally achieved its goals.

The border was moved tens of kilometers away from Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). Moscow also received the right to create a naval base on the Hanko Peninsula, which allowed it to take control of the Gulf of Finland.

General Terenty Shtykov (foreground right) examines ammunition of the Red Army men during the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940.

General Terenty Shtykov (foreground right) examines ammunition of the Red Army men during the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940.

At the same time, the victory had its share of negative consequences. The military campaign, which promised to be a walk in the park, instead turned into a severe test for the Red Army.

The fighting dragged on throughout the winter. The Soviet Armed Forces eventually lost more than 126,000 soldiers, either killed, missing or having died of wounds. The Finnish losses amounted to about 26,000.

A political commissar reading to soldiers the order to begin combat operations against Finland.

A political commissar reading to soldiers the order to begin combat operations against Finland.

The military prestige of the USSR suffered a serious blow. After the end of the war, Hitler called the Union “a colossus with feet of clay”.

The main reasons for this state of affairs were the dismissive attitude of the country's military and political leadership towards small Finland and the lack of proper preparation for the military campaign.

“We did not study Finland sufficiently in peacetime, we did not study it properly. During the pre-war drills, it was very easy for us, we reached Vyborg in no time, with a break for lunch,” claimed Sergei Semenov, the military commissar of the 50th Rifle Corps, after the war.

A dog-drawn sledge at the advanced base during the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940.

A dog-drawn sledge at the advanced base during the Soviet-Finnish war of 1939-1940.

The Soviet command underestimated the peculiarities of the theater of military operations. The troops had to move through dense forests along narrow roads, stretching out in long, poorly controlled columns. In such conditions, it was difficult to use tanks and the advantage in heavy artillery was reduced to almost zero.

“The Finns retreated in an organized manner, leaving nothing, neither living nor valuable, that could be useful to the army. I did not see a single Finn, they did not leave a single cattle or bird, the only thing that remained intact was the ground buildings,” recalled medic Boris Feoktistov.

The Red Army crossing in the area of Fort Ino on the Karelian Isthmus.

The Red Army crossing in the area of Fort Ino on the Karelian Isthmus.

Columns of Soviet troops became easy prey for mobile ski detachments of the enemy, who suddenly appeared from the forest, delivered a series of sensitive blows and quickly retreated.

“They fought skillfully and fiercely. And, most importantly, they ran fast on skis and were simply elusive. When we found them, we would go chasing them. But, when we would get through, the ‘cuckoos’ (snipers) would remain in the trees and shoot at us in the rear…” recalled infantryman Konstantin Aleinikov.

At the same time, the Red Army had practically no ski units at the beginning of the conflict. They began to be actively created only in early 1940, but the level of training of such units left much to be desired.

Destroyed Soviet equipment at Raate Road.

Destroyed Soviet equipment at Raate Road.

While on the Karelian Isthmus, Soviet troops had unsuccessfully tried to break through the Mannerheim defensive line, the strength of which became an extremely unpleasant surprise for them. In the Ladoga region and in northern Finland, regiments and even entire divisions were caught in “cauldrons”.

In severe frosts, many of the mostly lightly dressed Red Army soldiers died of frostbite. “People arrived in cold shoes, even in boots, not in shoes, and some of the boots were torn,” Lieutenant General Vladimir Kurdyumov, commander of the 15th Army, reported back to the leadership.

Captured Soviet armoured car on the Tolvajärvi front.

Captured Soviet armoured car on the Tolvajärvi front.

The combat training of personnel was also low. “Our fighters were often not literate enough in their knowledge of equipment and weapons. We had to train fighters during the war to master a heavy machine gun, a hand grenade, a light machine gun,” claimed Colonel General of Artillery Vladimir Grendal.

During the fighting, serious shortcomings in troop command were revealed. At a meeting with Stalin in April 1940, future Marshal Kirill Meretskov complained that the offensive often took place without careful preliminary reconnaissance, immediately en masse in an expanded order, which led to heavy losses.

Finnish soldiers near a captured Soviet tank.

Finnish soldiers near a captured Soviet tank.

The Soviet troops had very few submachine guns and mortars. Before the Finns demonstrated their high effectiveness in combat, they had been underestimated.

This is how division commander Mikhail Kirponos, commander of the 70th rifle division, described one of the battles: “The enemy is covered, it is difficult to hit them with fire and they hit our infantry with automatic and mortar fire, since we were not covered by anything and were advancing on ice, with a snow cover of up to 50 centimeters and more.”

A Finnish soldier with a Lahti-Saloranta M/26 in battle stations during the Winter War.

A Finnish soldier with a Lahti-Saloranta M/26 in battle stations during the Winter War.

In March 1940, at the cost of hard efforts, the Red Army managed to bring an end to the conflict.

Immediately after the end of the war, the country's top military and political leadership, headed by Stalin, carefully studied the bitter lessons of the confrontation with Finland. The Red Army immediately began large-scale transformations that continued until the invasion of Nazi Germany in the Summer of 1941.

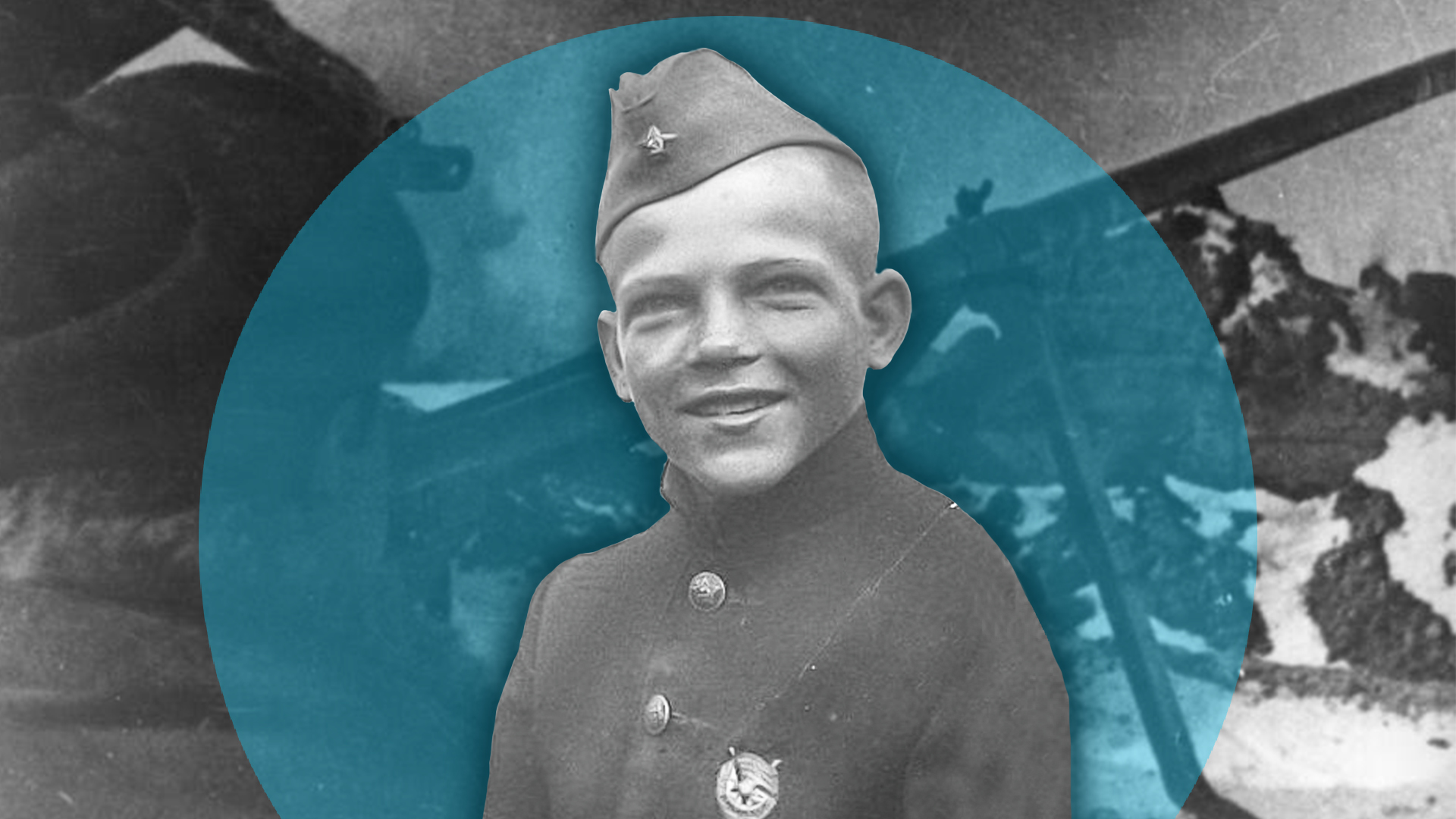

Soviet prisoner of war.

Soviet prisoner of war.