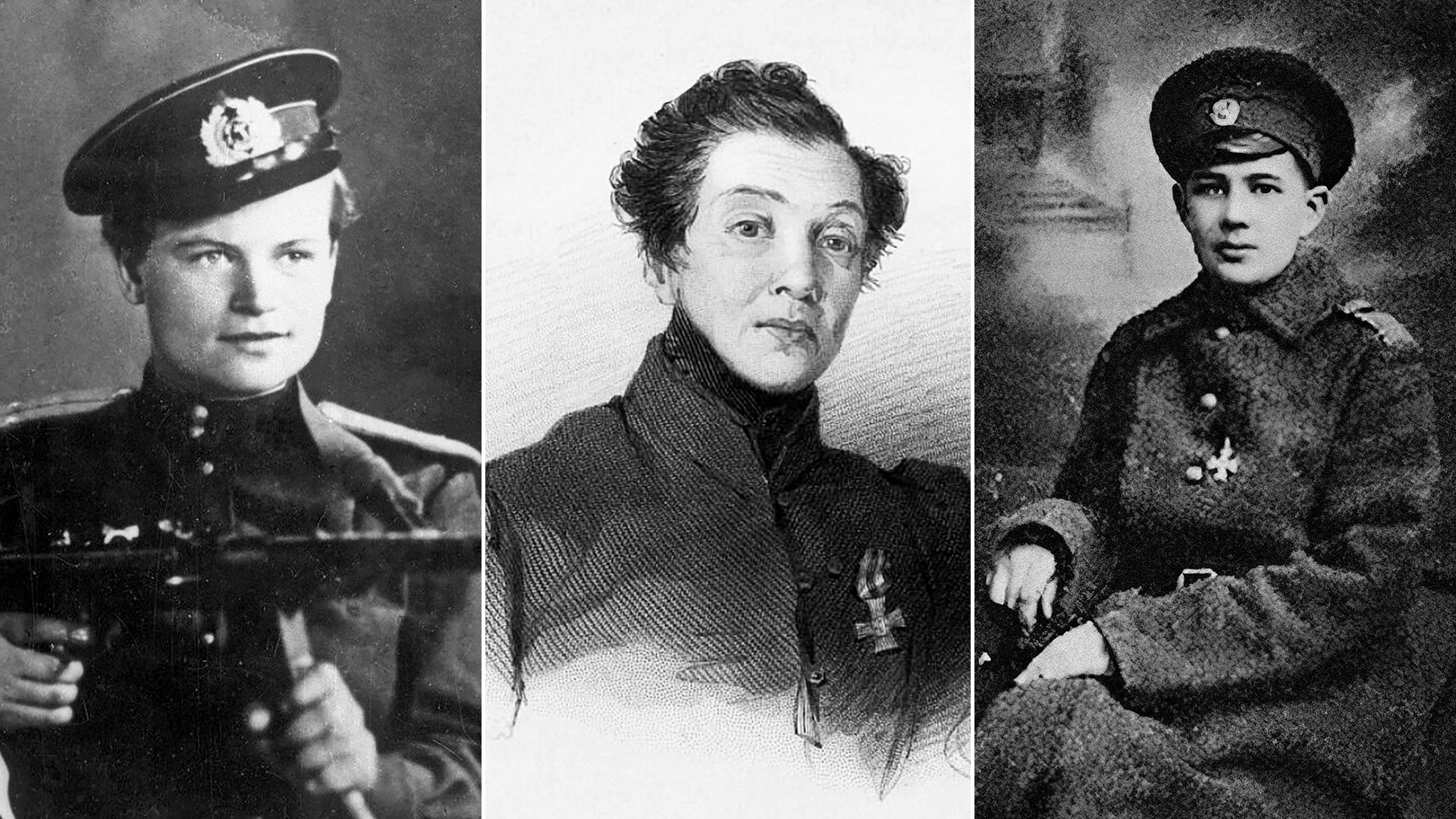

Nina Sokolova: The first Soviet female diver

"A young and energetic worker who constantly improves her knowledge and experience. Firm and persistent in achieving her goals. Forthright and bold. She has a keen interest in the naval profession… She is demanding and enjoys respect among her fellow servicemen and subordinates," is how Rear Admiral Fotiy Krylov once described Nina Vasilyevna Sokolova, the Soviet Union's first female diver.

A successful debut

Sokolova made her first professional dive in 1938 during the construction of the port in Sochi. As a hydraulic engineer, she was sent there to direct a group of divers.

At the time, the work of a diver was regarded as an exclusively male profession. It was assumed that Nina Vasilyevna would stay on shore all the time. But, she was unhappy with the plan.

She demanded to be provided with diving gear (a three-bolt diving suit, known simply as a ‘three-bolter’), so that she could personally supervise the progress of work under water. It was not an easy task: The suit had a weight of 80 kilograms, while the 26-year-old herself only weighed about 50 kilograms.

In the end, Sokolova not only coped, but also became passionately fond of diving.

First among Soviet women

Persistent and single-minded, Nina Vasilyevna managed to get herself accepted for training as a professional diver. To do so, she had to apply to the very top – permission was granted by then Chairman of the USSR Supreme Soviet Presidium Mikhail Kalinin himself.

A special diving suit was designed for the young woman, even though it was still rather heavy for her. In 1939, while in charge of the construction of a wharf in the town of Polyarny on the shores of the Barents Sea, she was already making regular dives in the icy water.

Once, Sokolova nearly died during the work. "She was supposed to jump from the stern into a boat. It was cold and, in her half-length sheepskin coat and ‘valenki’ [felt boots], she disappeared under the water with a splash. They got her out quickly, but she could easily have frozen. In a word, it was a baptism. They gave her a stiff drink," recalled Nina Vasilyevna's daughter Marina.

In besieged Leningrad

When the Wehrmacht invaded the USSR in the Summer of 1941, Nina Sokolova was serving as hydraulic engineer of an underwater technical operations detachment in the Baltic Fleet salvage and rescue service in Leningrad. On September 8, the city found itself encircled by the enemy.

Besieged by German and Finnish troops, Leningrad's only link with the "mainland" was by water across Lake Ladoga. This "Road of Life" was used to send food and ammunition to the city and to evacuate the population out of it.

In these conditions, the work of frogmen was vitally important. They laid a telephone cable along the bottom of the lake and also successfully brought up grain from sunken barges.

In the Spring of 1942, Sokolova put forward the idea of laying a pipeline along the bottom of Lake Ladoga to supply Leningrad with fuel. The long-suffering city only had a little over three months' supply of fuel left.

At the time, no-one in the world had any experience of building such underwater arterial pipelines. But Nina Vasilyevna's idea was given the go-ahead by the Kremlin.

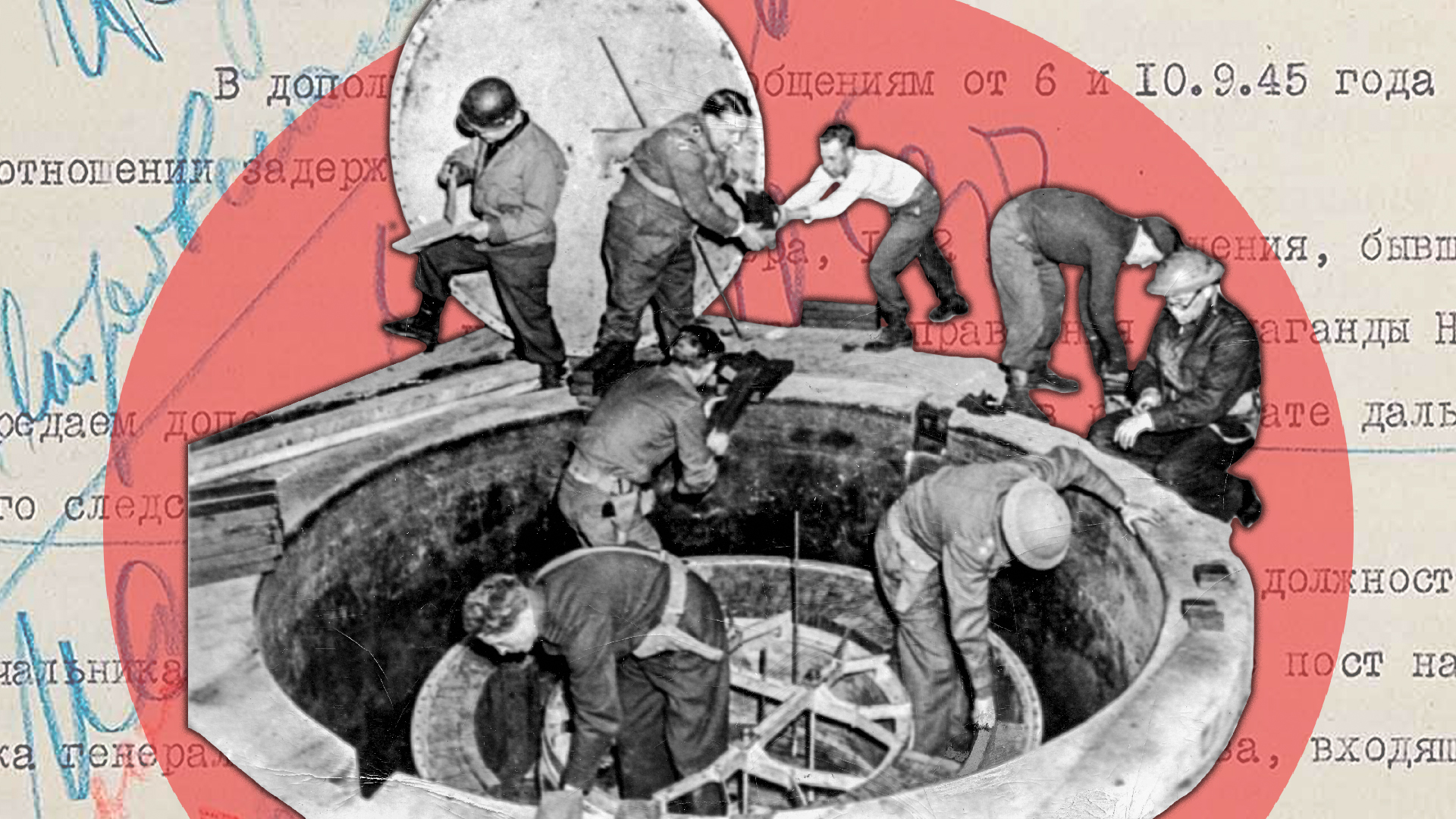

A bold project

Sokolova took part in surveying the bottom and finding the best route to lay the pipes. A sunken barge that stood in the path of the future gasoline pipe even had to be blown up.

The pipe laying literally proceeded under the noses of the enemy and was subject to constant shelling and bombing. In addition, the weather disrupted the work – on the very first day, a gale blew up on Lake Ladoga and a one-kilometer pipe string broke off and was carried away by the waves.

On June 16, 1942, after 43 days of work, the pipeline was commissioned for use. It was 29 km long, 21 km of which were under water at depths of up to 35 meters. The gasoline pipeline's throughput was around 350 tons of fuel a day. In all, it was to supply Leningrad with more than 40,000 tons of gasoline.

In Summer and Fall of 1942, Nina Vasilyevna was involved in laying a high-voltage cable to bring electricity to the besieged city, which came to be known as the ‘Cable of Life’. During her work, she ended up being concussed and sustained leg and shoulder injuries.

Civilian life

After the war, Naval Engineer Lieutenant-Colonel Sokolova was involved in restoring damaged bridges and port infrastructure in Leningrad and Tallinn. She, subsequently, devoted herself to teaching.

Nina Vasilyevna's awards included two Orders of the Red Star, Orders of the Patriotic War 1st and 2nd Class and the medals 'For the Defense of Leningrad' and 'For Battle Merit'. All told, she spent 644 hours, equivalent to almost 27 days, under water in her lifetime.