How vodka helped the Red Army defeat the Nazis

The Eastern Front of World War II was a living hell on earth: artillery bombardments and air raids which left nothing alive, terrible tank attacks, mass deaths of comrades… To preserve physical and moral strength under such conditions was a very difficult task for soldiers.

The leaders of the warring states were well aware of the problem and invented all kinds of means to keep their soldiers in good shape. Thus, German soldiers raised their morale with schnapps. The Wehrmacht also used Pervitin tablets. This drug, based on methamphetamine, had a strong psychostimulant effect on the central nervous system, causing a burst of energy and reducing the need for sleep and food.

In the Red Army, the problem of stress was solved in a similar way, namely through the most famous Russian drink - vodka.

The ‘People’s Commissar 100 grams’

The tradition of giving soldiers alcohol “for courage” has existed in the Russian army since ancient times. As early as the 18th century, soldiers were entitled to three glasses of “bread wine” a week during combat operations.

In 1908, after Russia’s disastrous defeat in the war against Japan, it was decided to stop this practice and, thirty years later, the People’s Commissariat of Defense issued a decree ‘On Combating Drunkenness in the Red Army’, under which especially zealous drinkers could be fired from the armed forces and even put on trial.

The alcohol tradition returned to the army during the war against Finland. In January 1940, Commissar of Defense Kliment Voroshilov suggested issuing 100 grams (milliliters) of vodka and 50 grams of salo (pork fat) per day to the soldiers and commanders to keep warm in severe winter conditions. The tank crews were given double portions of vodka rations, while the pilots often received cognac.

Stress control

When the war against the Finns was over, distribution of alcohol to the troops was stopped, but, in a year and a half, it was restored again. On August 22, 1941, the decree of the State Committee of Defense under the number 562 stipulated daily distribution of 40 percent alcohol vodka among the front line soldiers (who were in direct contact with the enemy) in the amount of 100 grams (milliliters) per person.

An order of the People’s Commissariat of Defense, which came out three days later, specified that, on an equal basis with the front line units, the Red Army Air Forces pilots, as well as the engineering staff serving the field airfields, were to be provided with vodka.

Of course, this initiative of the military leadership of the country was caused by completely different reasons than during the Soviet-Finnish conflict. The regular issue of alcohol was supposed to help soldiers cope with the enormous stress they experienced during the most difficult initial period of the war against Nazi Germany. In addition, it was strong alcohol with high alcohol content that was quickly broken down in the human body, converting into a significant amount of energy and allowing a rapid replenishment of large energy expenditures.

Help or harm?

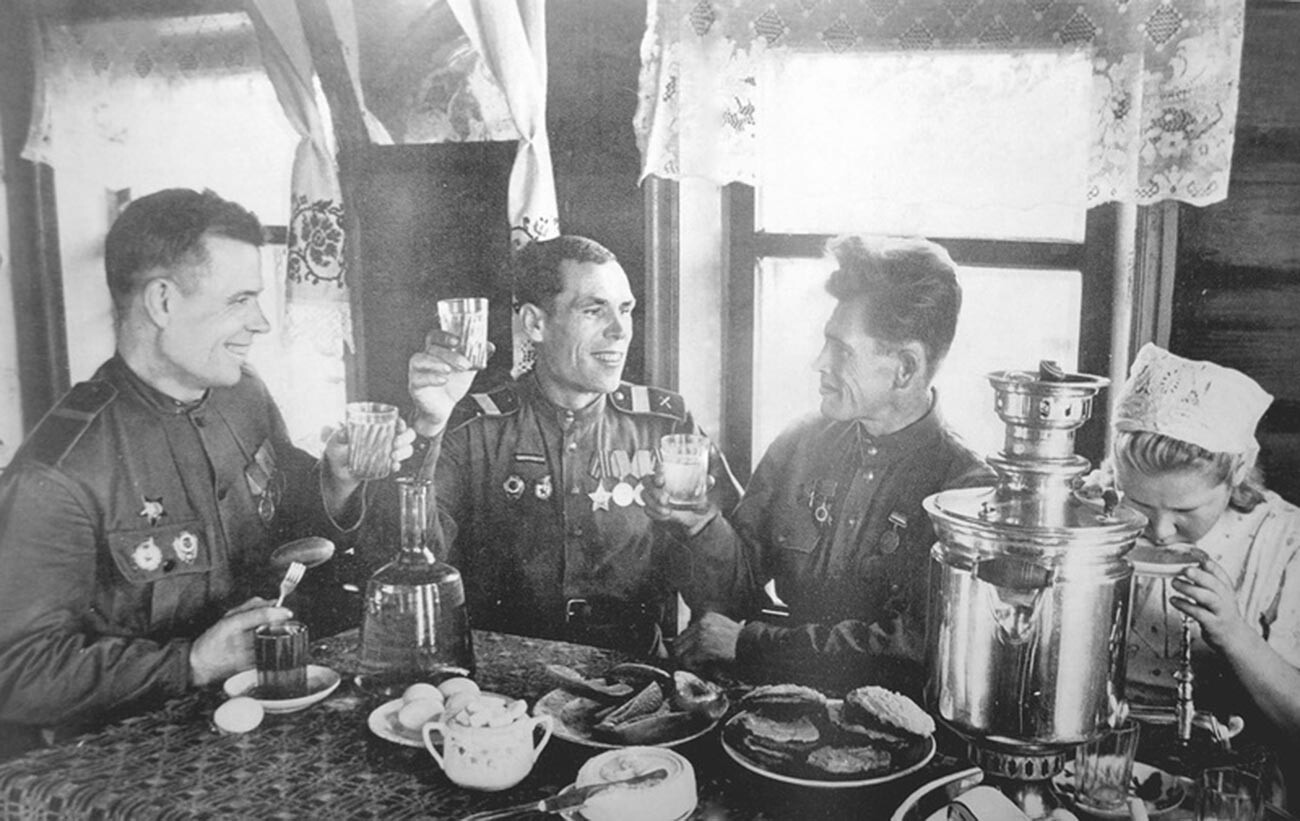

The system for distributing vodka to soldiers in different units and formations could vary greatly. Somewhere, alcohol was given to soldiers before an attack, somewhere after a hard battle and, in some regiments, “fire water” in general was delivered very rarely.

“I remember that vodka was given out only before the attack,” claimed Private Alexander Grinko: “The foreman walked along the trench with a mug and whoever wanted it poured it for himself. The young men were the first to drink. And then they went straight under bullets and died. Those who survived several fights were very wary of vodka.

“Without alcohol it was impossible to defeat… the cold,” said Senior Lieutenant Fedor Ilchenko, who captured Field Marshal Friedrich Paulus in Stalingrad: “‘Front hundred grams’ became more expensive than shells and saved soldiers from frostbite, since many nights they spent in the open field on bare ground.”

Not all soldiers, however, needed regular servings of alcohol. “In the first years, I exchanged it for sugar,” recalled machine gunner Mikhail Larin: “So, when the foreman handed out a hundred grams, the soldiers walked around me like geese. So I exchanged those hundred grams. “We, the youth, were not much interested in the presence or absence of ‘one hundred grams’, we were incomparably more interested in the meal,” claimed Guard sergeant Georgy Veliaminov.

Bad habit

The rules and norms of vodka distribution were constantly changing. From May 1942, alcohol was given only to soldiers of units that had distinguished themselves during battles. Thus, their rate was raised to 200 grams (milliliters). The rest of the front line soldiers were only supposed to drink on the holidays.

In November of the same year, it was decided to return to traditional 100 grams which were given out only to soldiers and officers who were directly involved in military actions. The reserve servicemen and the employees of the rear services were to be provided with just 50 grams.

Not everywhere were military men provided only with vodka. For example, for the Soviet troops defending the Caucasus, this stimulant was successfully replaced with local wines.

After Victory Day, “100 grams of vodka” was canceled in the Red Army. However, not all of those who came back from the war managed to break the habit of drinking every day.

Lev Kartashev, a veteran of the 83rd Guards Rifle Division, recalled: “Already after the war in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg), I used to go to the officers’ mess hall for lunch. And it seemed to me simply wild that officers did not sit down to eat without a hundred grams… And where there’s a hundred, there’s two hundred and more… I remember watching that picture and thinking: ‘Yes, we’ll go far…”