The ‘Book of Veles’: How a false doctrine gained thousands of followers in the 1990s

“Back then, there was Bogumir, the husband of Slava, and he had three daughters and two sons. And their mother, whose name was Slavunya, <…> told Bogumir on the seventh day: ‘We need to marry out our daughters, to see our grandchildren.’ And Bogumir harnessed his cart and went where his eyes took him. He reached an oak standing in a field and stayed to spend the night by the campfire. And he saw in evening twilight three men approaching him on horseback. <…> Bogumir returned to his steppes and brought three husbands for his daughters. From there, three lineages began. From there, come the Drevlians, the Krivichis and the Polans, for the first daughter of Bogumir was called Dreva, another – Skreva and the third one – Poleva. Bogumir’s elder son was called Seva and the younger one – Rus. From them come the Severians and the Rus’. The three husbands were Utrennik, Poludennik and Vechernik.”

This is the legend of the origin of Slavs, according to the ‘Book of Veles’ – allegedly an ancient chronicle that tells the story of the peoples of Eurasia from the 9 century B.C. No one has ever seen the original version of this document. But that didn’t prevent the ‘Book of Veles’ from becoming incredibly popular – there were more than 10 translations – and from becoming one of the main “doctrines” of neo-pagans.

The history of the book

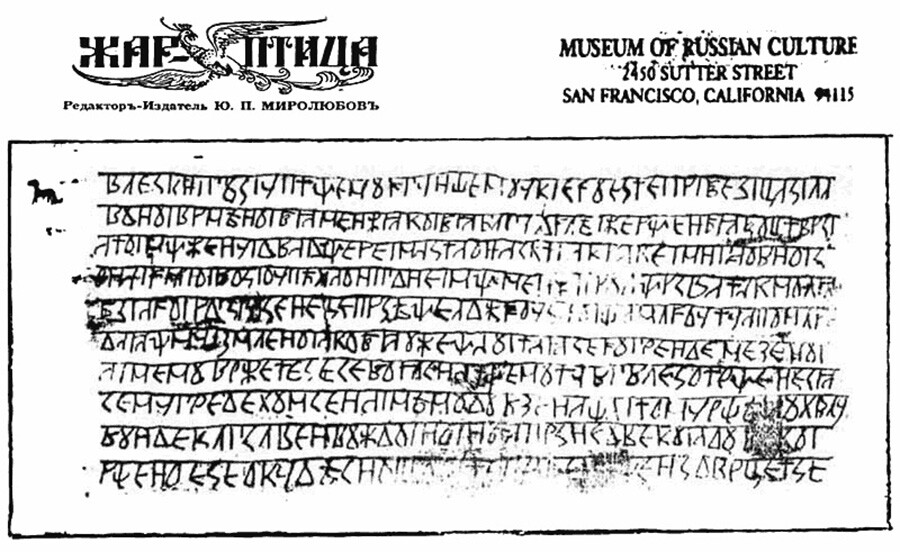

The author of this hoax was Russian emigrant Yuri Mirolyubov. In 1952, he sent a letter to the editorial board of the Russian-language magazine ‘Zhar-Ptitsa’ (‘Firebird’) that was published in San Francisco. Allegedly, Mirolyubov had discovered some ancient planks from the 5th century that told the history of Ancient Russia. In 1955, the magazine published the only picture – a photo of the text, copied from the plank. From 1957 to 1959, the magazine released the translation of the full “text from the planks”, done by Mirolyubov and emigrant Alexander Kurenkov, another fan of ancient artifacts, with whom he corresponded.

Image claimed to be "Photograph of Isenbeck's Plank No. 16", Magazine ‘Zhar-Ptitsa’, San Francisco (1955)

Image claimed to be "Photograph of Isenbeck's Plank No. 16", Magazine ‘Zhar-Ptitsa’, San Francisco (1955)

Mirolyubov himself called the artifact ‘Isenbeck's Planks’. According to him, they belonged to artist Fyodor Isenbeck, who discovered them during the years of the Russian Civil War in one of the plundered estates and brought them along across Europe after his emigration. In 1925 in Brussels, he became acquainted with Mirolyubov and let him study the planks over 15 years.

“He was incredibly suspicious about any advances towards the ‘planks’. He didn’t even give them to me to take home! I had to sit in his tailor shop, on rue Besme in Uccle; there, he locked me in with a key – once, I spent two days in such imprisonment! When he came back, he was utterly surprised. He completely forgot I was in his tailor shop,” Mirolyubov wrote to Sergei Lesnoy, another researcher of the planks.

In 1941, during the Nazi occupation of Belgium, the artist died and traces of the “artifact” disappeared.

The phrase ‘Book of Veles’ began to be used in 1966 with Lesnoy’s suggestion. Overseas, he published his work ‘Book of Veles’ with his own transcription of the planks and excerpts from his correspondence with Mirolyubov.

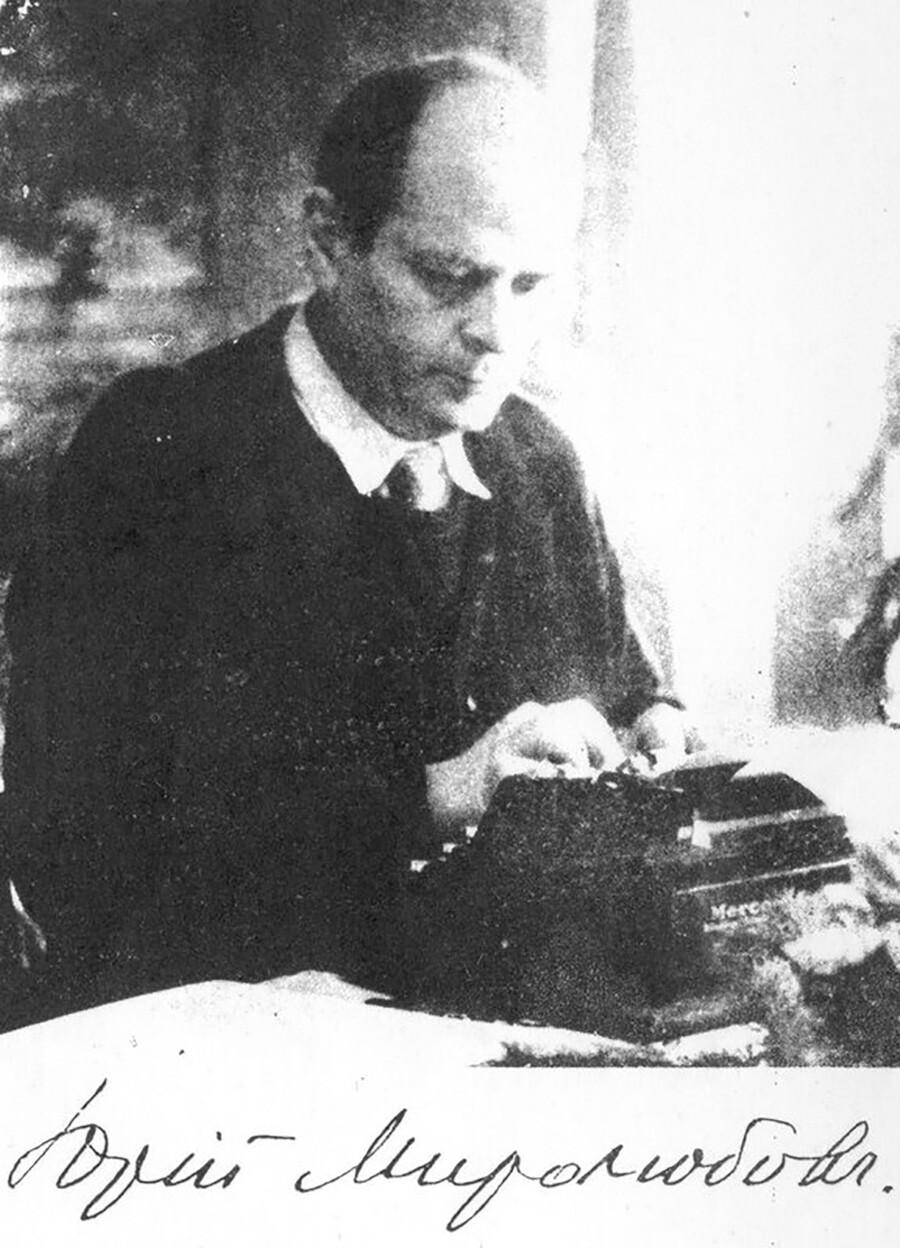

Russian emigrant writer Yuri Mirolyubov (1892-1970)

Russian emigrant writer Yuri Mirolyubov (1892-1970)

Scientists’ opinion

Many reputable Soviet paleographers, historians, archaeologists, linguists and literary scholars agreed that ‘Isenbeck's Planks’ was a fake. Everything alarmed them about the history of the “artifact”: from the absence of information about the first owners of the planks to the alphabet, as well as the genre and linguistic peculiarities of the translation.

The text has contradicting dates, the count of time is conducted in an uncharacteristic way for chronicles, there are no toponyms specified, no names of tsars or commanders, the narratives of significant events were not laid out; but, there were anachronisms. There were also discrepancies between the texts published by ‘Zhar-Ptitsa’ and Mirolyubov’s archives that were later acquired by scientists.

Separately, scientists analyzed the alphabet and the grammatical structure of the language: for that, a reproduction of the text from a plank was enough. The analysis showed a chaos of forms made of modern Slavic languages, a variety of ways of writing for the same words and never-before-seen methods of word formation. The script itself – the so-called ‘Velesovitsa’ – was an imitation of the Cyrillic script with a top horizontal line similar to the Indian Devanagari.

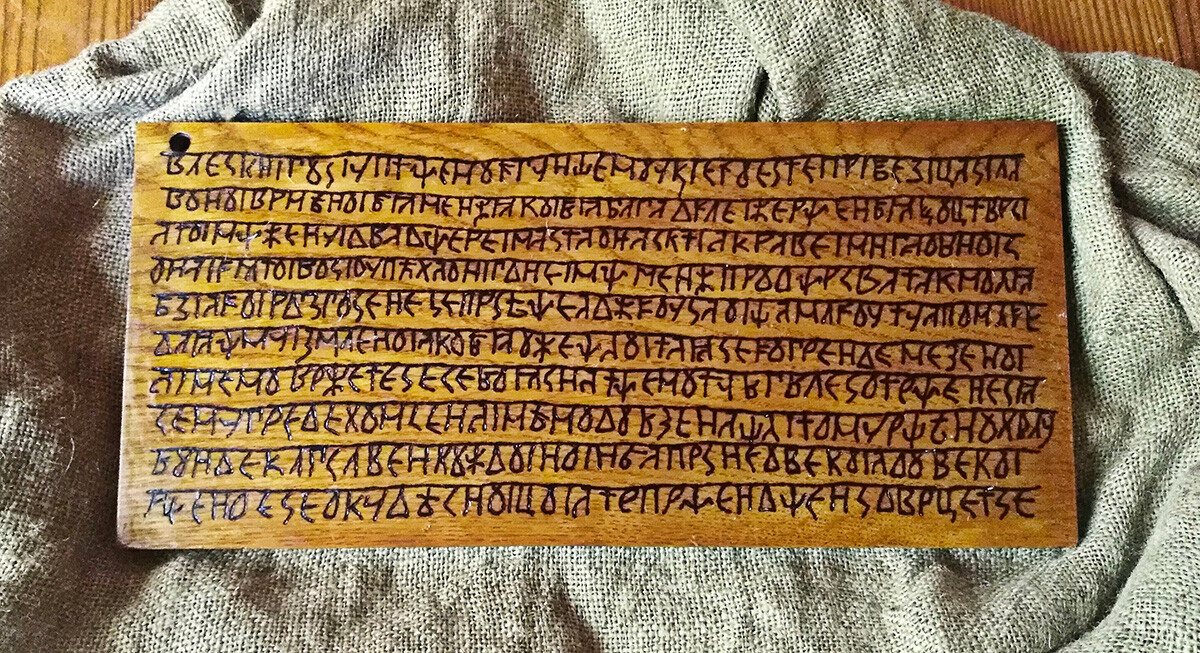

Photo of the reconstruction of ‘Isenbeck's Planks’

Photo of the reconstruction of ‘Isenbeck's Planks’

“The analysis of the ‘Book of Veles’ proves that the language in which it’s written couldn’t have existed. There’s no such language that wouldn’t have an established phonetic system, unified grammar rules and would violate in such a way all the well-studied development patterns of all Slavic languages,” Soviet literary scholar and medievalist Oleg Tvorogov wrote.

He also took note of the narrative and graphic similarities between the ‘Book of Veles’ and the works of Alexander Sulakadzev, a hoaxer of the 18th-19th centuries. The latter created both “ully-authored” counterfeits and fake additions to genuine manuscripts which increased their age.

Despite the flimsiness of the ‘Book of Veles’ as a historical document, interest towards it grew beyond academic circles. Its text, in particular, drew the attention of the followers of Russian paganism.

In 1976, the mass weekly ‘Nedelya’ (‘The Week’) released an article about the ‘Book of Veles’, which the authors presented as a “mysterious chronicle that offers a new outlook of the times when Slavic writing emerged and allows us to reconsider the scientific understanding of the origins and the mythology of Slavs”. This piece didn’t call the accuracy of the dubious text into question and helped its further distribution.

What’s the secret of the ‘Book of Veles’ popularity?

“The biggest problem related to the ‘Book of Veles’ is not from linguistics and not from history, but from the sphere of social psychology. It consists of the fact that its falseness is clearly in view only to professional linguists and historians, while an untrained reader easily falls victim to primitive – yet, appealing for many – fiction about how ancient Russians bested their enemies several thousand years ago. The statements of science, alas, can’t outweigh the attractive fantasies of amateurs in the eyes of such a reader,” Soviet and Russian linguist and academician Andrey Zaliznyak notes.

The translation of the planks was published on the territory of Russia only in 1992 – and republished dozens of times later. From the same year onward, newspapers and magazines wrote about the ‘Book of Veles’, never doubting its authenticity – nationalistic publications, socio-political publications (‘Moskovsky Komsomolets’ – ‘Moscow Komsomolets’) and even popular science publications (‘Nauka I Religiya’ – ‘Science and Religion’, ‘Chudesa I Priklyucheniya’ – ‘Wonders and Adventures’). In the middle of the 1990s, it was even mentioned in an experimental history textbook for high school. References to it also appeared in professional publications for history teachers.

Interest towards Neo-Paganism in the 1990s didn’t grow from nowhere: it existed both in pre-Revolutionary Russia – in the Slavophile circles and in the USSR. In Soviet times, the fascination with archaic Slavic culture was supported from the top to undermine the significance of Orthodoxy, which the Communist Party presented as a “tool of the enslavement of Slavs”. As such, paganism justified communist ways and helped the authorities to fight Christianity.

In the 1960s in Soviet cinema, the theme of Slavic paganism was raised in the film “Andrei Rublev” by Andrei Tarkovsky (1966), in the short story “Holiday”. -

In the 1960s in Soviet cinema, the theme of Slavic paganism was raised in the film “Andrei Rublev” by Andrei Tarkovsky (1966), in the short story “Holiday”. -

Then, after the collapse of the Soviet Union, society delved into an identity crisis. Many, once more, turned to paganism for answers.

“There was psychological necessity in it. People stepped away from one ideology and they needed another. A part of them turned to traditional religion, another part embarked to find aliens, some turned to Neo-Paganism,” St. Petersburg State University teacher and historian-anthropologist Sergei Yegorov notes.

The demand for a new ideology was actively fueled by novelists: Russian authors learned and “creatively re-imagined” the narratives of the ‘Book of Veles’, dedicated to the greatness of pre-Christian Russia.

“Along with the collapse of the communist ideology, the black pillar of mystical nonsense of all kinds arose and, with it – an army of opportunists, making good cash off fools, idiots and enchanted wanderers,” writer Sergei Alexeev later admitted, whose works had a great influence over the development of Slavic Neo-Paganism.

Sergei Alekseev

Sergei Alekseev

The material, supplied by the ‘Book of Veles’, was perfectly fit for constructing a new, attractive ideology. The book, in particular, claimed that Slavic paganism was a peaceful religion that had no human sacrifices. However, official science proved the opposite.

“Neo-Pagan ideologists realized better than anyone else the flimsiness of the constructs known to them, based on much outdated data and obsolete methodical approaches. They needed a genuine original source like a gulp of fresh air to refer to it as to the last undeniable proof. It’s not a coincidence that, over the course of decades, amateur enthusiasts persistently, although fruitlessly, sought artifacts of the most ancient Slavic writing. So the ‘Book of Veles’ was a blessing from God upon them,” historian Viktor Shnirelman stresses.

Participants of the pagan festival of the summer solstice 2017

Participants of the pagan festival of the summer solstice 2017