Why did the Russian Orthodox Church canonize a Nazi soldier?

“Let us thank God for the strength he gives us in the fight against Satan. Let us die if we must, but at least many Germans will finally have their eyes opened.” Thus wrote Alexander Schmorell, a German soldier who defied Hitler and who would be declared a saint after his death, in a letter to his sister from death row.

An Orthodox Christian German

Schmorell was born in 1917 in the family of a Russified German in the Russian city of Orenburg (today on the border with Kazakhstan). His mother, who was of Russian heritage, died of typhus when the boy was not even two.

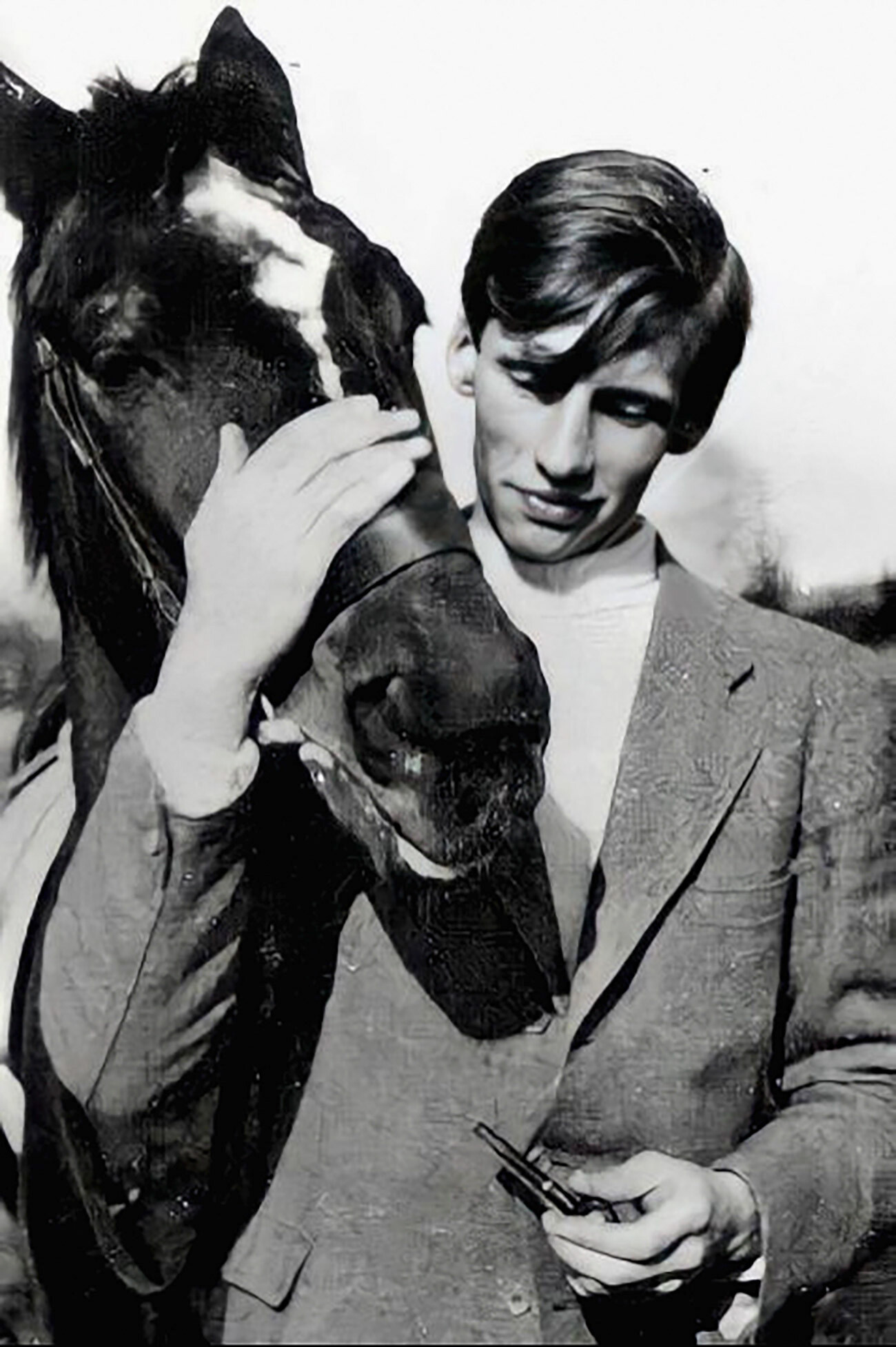

Alexander Schmorell.

Alexander Schmorell.

In 1921, Schmorell’s father decided to flee Russia, which had been engulfed in the Civil War, and moved to Germany, along with his second wife and little Alexander.

Since the boy’s stepmother and nanny were also Russian, he didn’t forget the language of his birth. Furthermore, Russian traditions were held dear in the family: During meals, there was always a samovar on the table, while blini (pancakes) and pelmeni (dumplings) were often served.

By religious denomination, Alexander Schmorell was Orthodox Christian and he often attended church in Munich. He loved Russia all his life, although he didn’t share the ideology of the Bolsheviks.

The White Rose

Aversion to communism did not mean, however, that Schmorell supported the Nazis. On the contrary, to him, Adolf Hitler was an even worse evil and he regarded the Fuehrer of the German nation as a truly demonic individual. “It’s somehow got very uncomfortable here and there’s a whiff of sulfur in the air,” Schmorell once told a female acquaintance when Hitler and his entourage entered a restaurant in Munich in which they were sitting.

Alexander Schmorell.

Alexander Schmorell.

In 1937, Schmorell was called up into the army, but he refused to swear an oath of allegiance to the head of state and it was only through the efforts of his commander that the story was hushed up. The second time Alexander ended up in the armed forces was in 1940. As a medical student at Munich University, he participated in the French campaign, serving in a medical unit.

After seeing enough of the “achievements” of National Socialism, the future doctor was determined to oppose it in any way he could and he was far from alone in this aspiration. In 1942, along with his friend and fellow student Hans Scholl, he organized the underground organization called the ‘White Rose’, in which they were soon joined by several other students and even one professor.

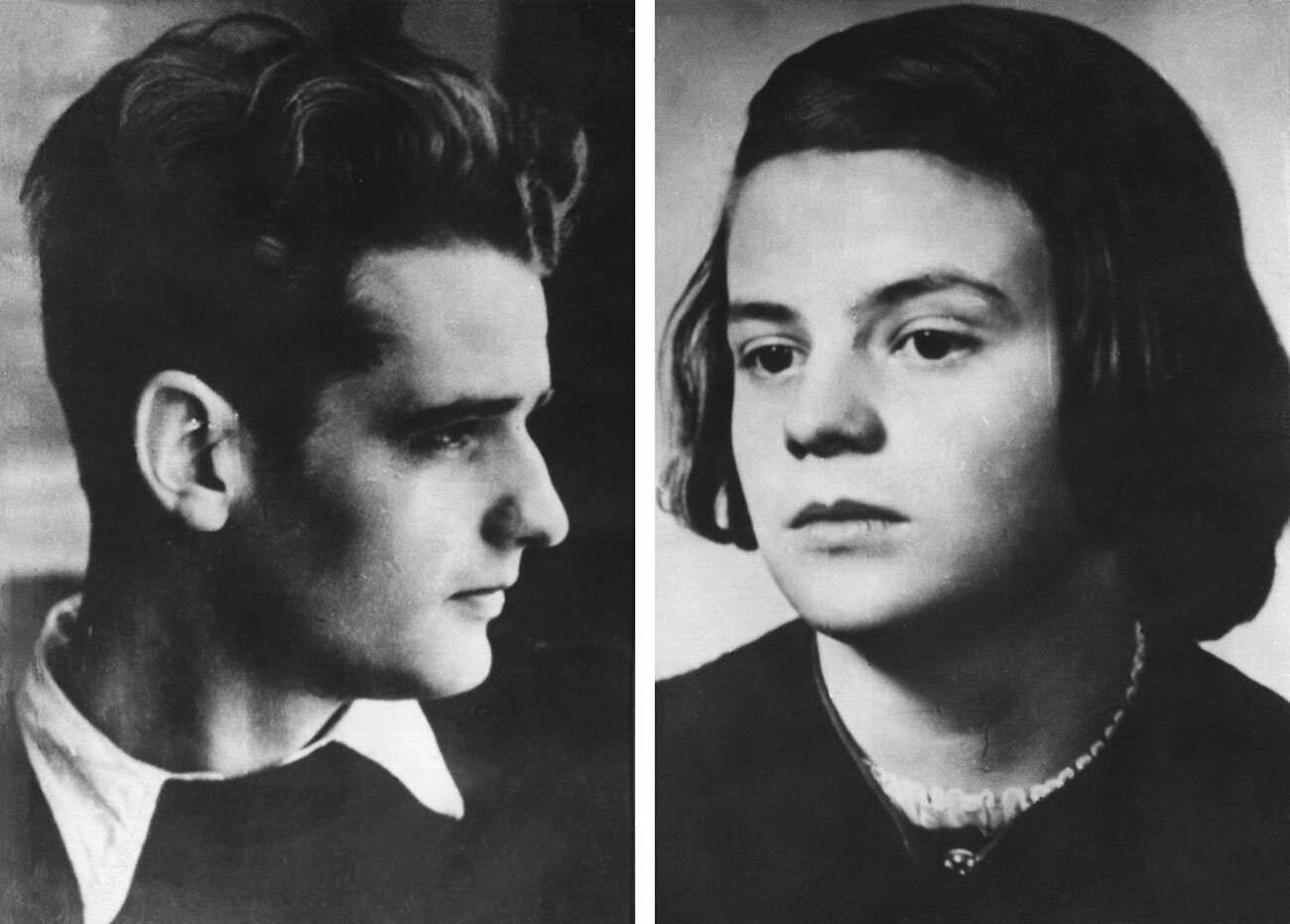

Members of the White Rose underground organization.

Members of the White Rose underground organization.

“Our friends and us were so different, reflecting, so it seemed, the richness of human personality, but, it turned out that this was precisely the principal danger to the nation, to the national idea,” wrote Hans Scholl’s sister, Sophie, also a member of the ‘White Rose’. “Somehow, without being aware of it, we were all put under flags and taught to march, to walk in formation, not to object and to think collectively. We loved Germany so much that we had never asked ourselves ‘for what and why’ we loved our country. With the rise of Hitler, we began to be taught and have it spelled out to us ‘for what and why’ we should love our country.”

The members of the clandestine group printed and distributed leaflets calling for resistance to the Nazi regime. “Shouldn’t every honest German today be ashamed of their government?” proclaimed the first of the leaflets. In addition, thanks to the effort of members of the ‘White Rose’, slogans such as “Down with Hitler” and “Freedom” appeared on buildings in Munich.

Hans and Sophie Scholl.

Hans and Sophie Scholl.

Schmorell took it very badly when Germany invaded the USSR in 1941 and, in 1942, he was even forced to take part in the invasion. Along with Scholl, he spent three months in the area of the town of Gzhatsk near Smolensk as a member of a medical company in the 252nd Infantry Division. Alexander was lucky not to end up on the front line. He mixed a lot with the local population, finding further confirmation that Hitler was an absolute evil and that Germany, Russia and the whole of the rest of the world needed to be rid of him.

Saint

On February 18, 1943, the ‘White Rose’ organization was exposed. An employee at the Munich University detained Hans and Sophie Scholl as they were leaving leaflets in empty auditoriums and corridors in the university building. Alexander Schmorell, who had a 1,000-Reichsmark reward on his head, was also detained soon afterwards.

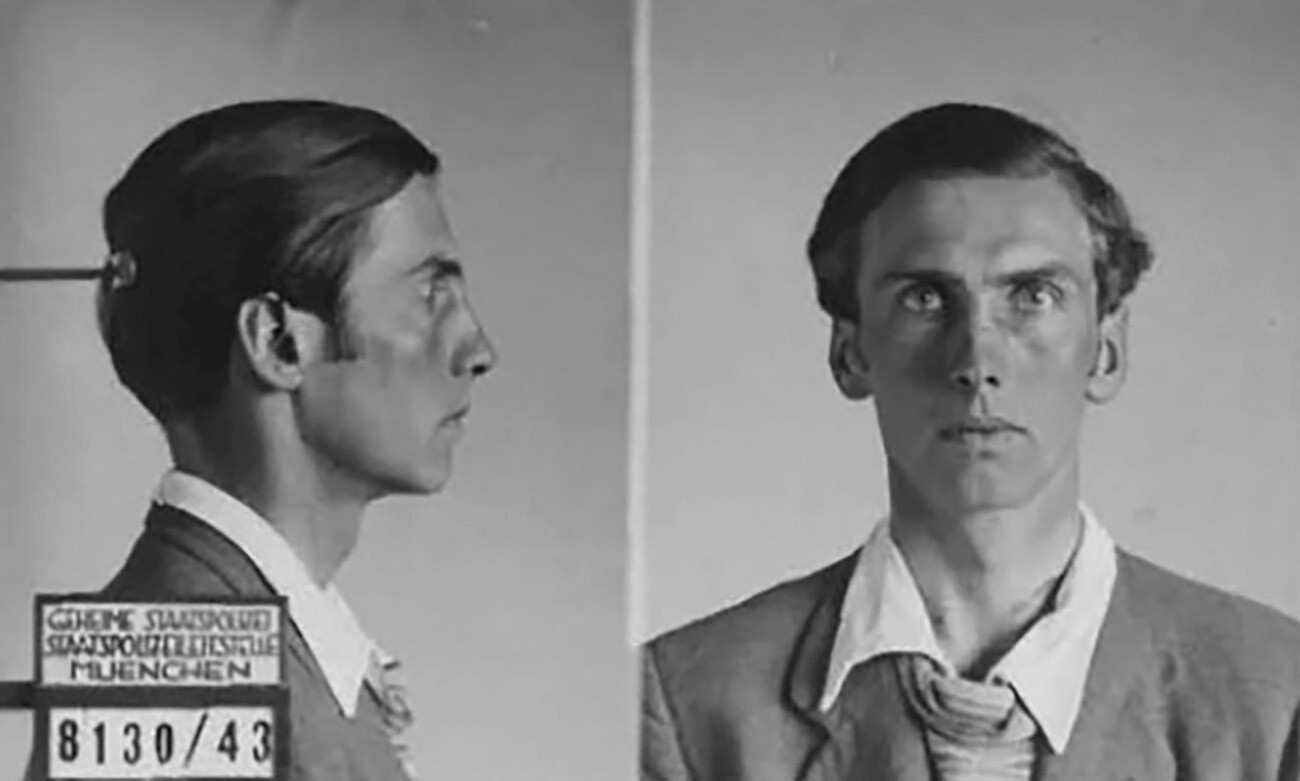

Gestapo photos of Alexander Schmorell, taken after his capture.

Gestapo photos of Alexander Schmorell, taken after his capture.

The members of the underground organization came before the People’s Court, presided over by Roland Freisler. This former communist and member of the Bolshevik party had lived and worked in the Soviet Union for a time, before moving to the third Reich, where be became a fervent and fanatical Nazi. Four days after their apprehension, he sent Christoph Probst and Hans and Sophie Scholl for execution.

However, the Schmorell case continued until the summer of 1943. Alexander’s uncle, Rudolf Hoffmann, one of the longest-standing members of the National Socialist German Workers’ (Nazi) Party, appealed to Heinrich Himmler on his behalf. The Reichsführer-SS’s reply was categorical: “The ignominious actions of Alexander Schmorell, which without the slightest doubt were significantly influenced by the fact that he has Russian blood, deserve a just punishment.”

Russian Orthodox Priest carry an icon resistance fighter Alexander Schmorell in the Cathedral for the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia in Munich, Germany, 04 February 2012.

Russian Orthodox Priest carry an icon resistance fighter Alexander Schmorell in the Cathedral for the Holy New Martyrs and Confessors of Russia in Munich, Germany, 04 February 2012.

While in prison, Schmorell did all he could in his letters to reassure his family: “If I have to die, know this: I do not fear death… The Lord directs the course of events as he sees fit, but he does it for our benefit. That is why we must place our trust in him…” “I have fulfilled my mission in this life and I wouldn’t know what else I have to do in this world,” he confided to an Orthodox priest who came to take his confession after the death sentence was passed.

On July 13, 1943, Alexander Schmorell was executed by guillotine. In Germany today, streets, squares, schools and parks are named in his honor and that of other members of the underground ‘White Rose’ group. A memorial to the courageous medical student stands in Orenburg, the city of his birth. And on February 4, 2012, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized Schmorell as a saint.