How an adventure novel saved the life of a writer in the Gulag

Events in the book take place in the 18th century. In the Indian Ocean, a pirate ship commanded by a one-eyed captain seizes another ship on which the heir to an earldom and his bride are sailing from Calcutta to England. One of the pirates takes the earl's documents and sails to England under his name - and with his bride.

This is how the plot of the adventure novel The Heir from Calcutta begins. What does Russia have to do with all this, you might ask? Well, the book was written by a Soviet writer and, what is more, he wrote it while imprisoned in the Gulag and it helped him to survive. But let's start at the beginning.

Sent to the Gulag for 'idle chatter'

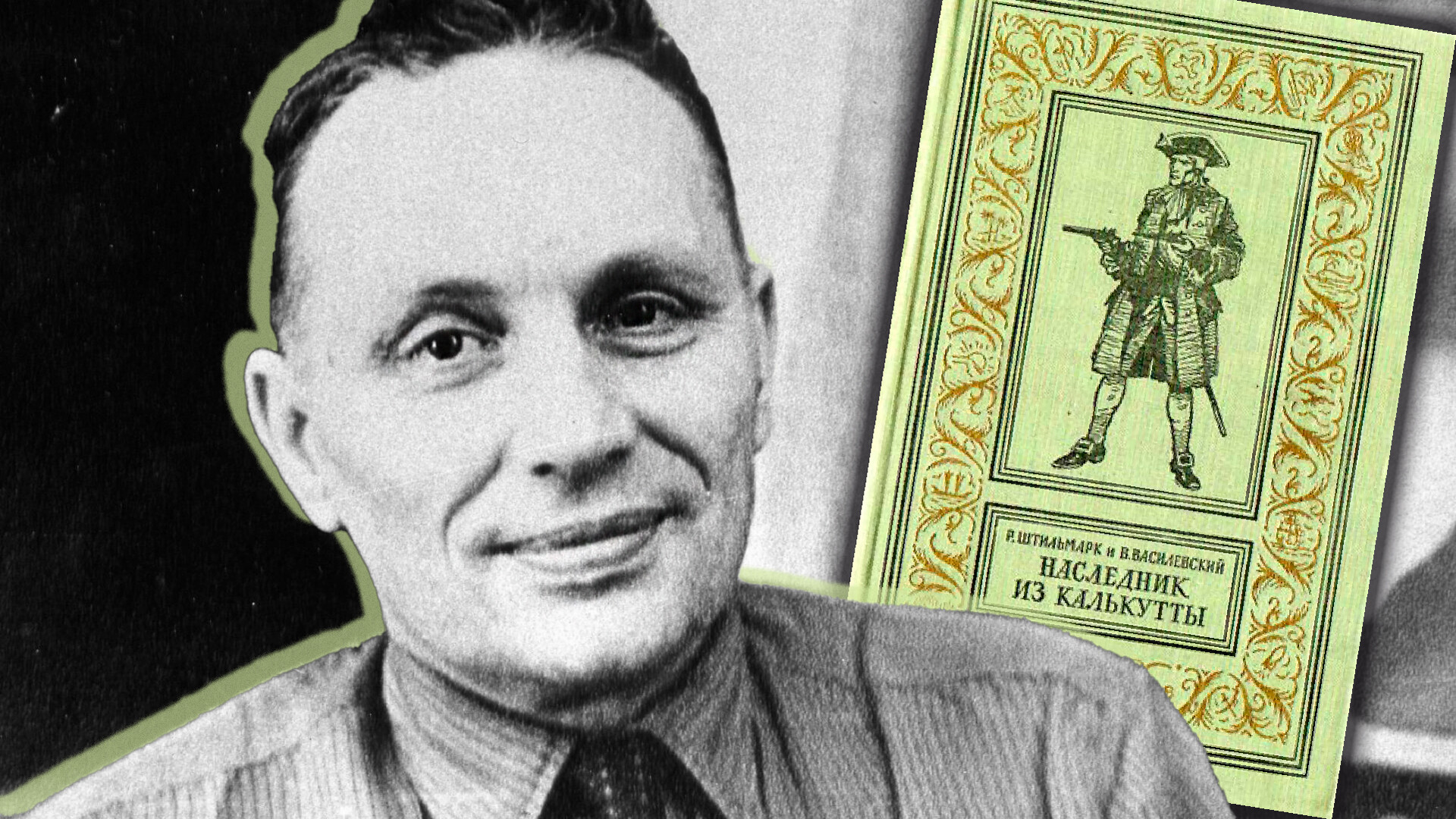

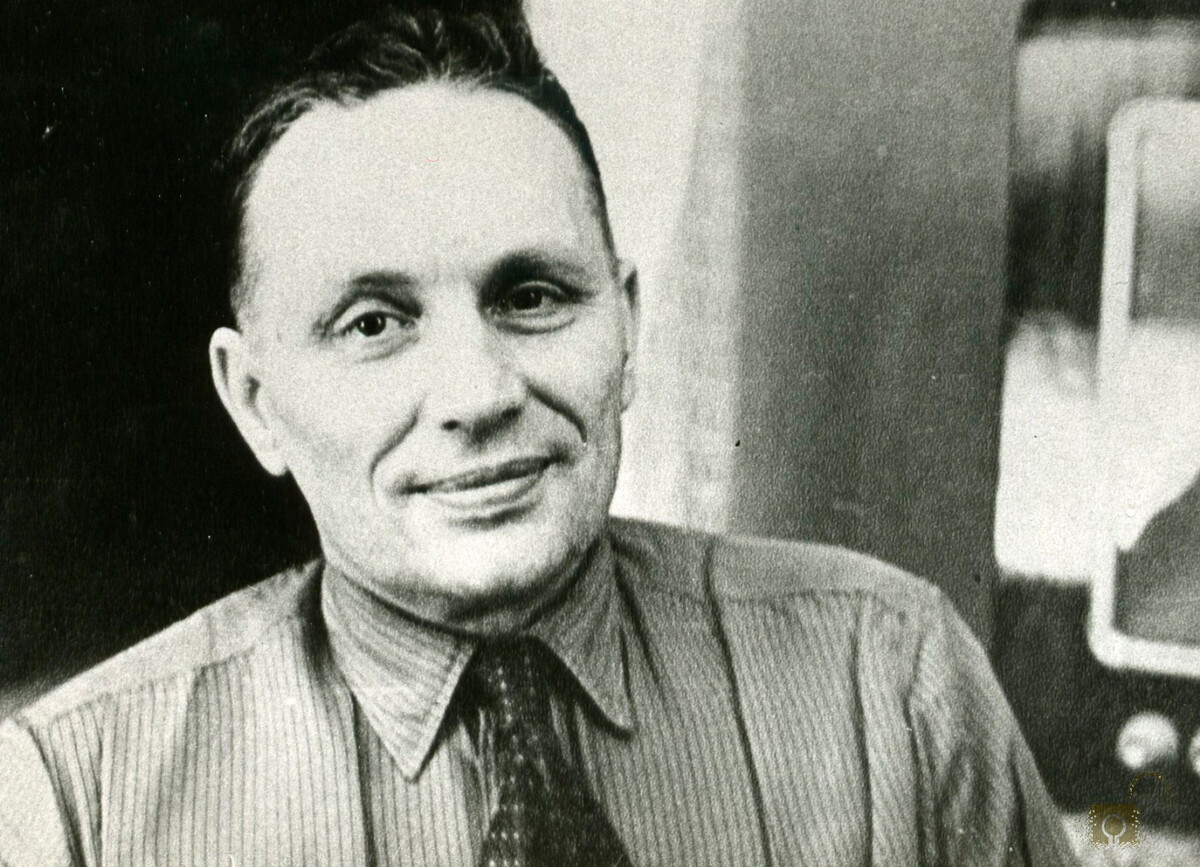

Robert Shtilmark

Robert Shtilmark

Robert Shtilmark had German and Swedish roots but he was born in Moscow in 1909. Graduating from one of the first literary institutes established by the new Soviet authorities, he became an international affairs journalist, focusing on cultural relations with Sweden and writing for major literary journals.

During World War II, he served in a Red Army reconnaissance company and was seriously wounded, after which he trained as a military topographer and joined the General Staff. In April 1945, just a month before the end of the war, Robert was arrested and sentenced to 10 years in labor camps under Article 58-10 for "counter-revolutionary agitation" - or "idle chatter", as it was popularly known. Allegedly, Shtilmark didn't approve of the Stalinist redevelopment of Moscow - in particular, the demolition of the Sukharev Tower and the Red Gate - as well as the Soviet predilection for renaming cities.

Robert spent three years in prisons not far from Moscow and was then transferred to the north where construction of the "Transpolar Mainline Railway", one of the most ambitious Gulag projects, had just started. It was supposed to connect the northern regions of the country from the Barents Sea to Chukotka across swampy ground (in the summer) and frozen tundra (in the winter).

Abandoned sites of the "501 Railroad"

Abandoned sites of the "501 Railroad"

Shtilmark was sent to work on the railroad’s eastern stretch - the Salekhard-Igarka section. The project was never completed- after Stalin's death work ceased and the prisoners were amnestied en masse.

A novel written in order to survive

In the camp, political prisoners were kept together with ordinary criminals. Many of the latter sought favor with the prison administration and even managed to get "administrative roles" in the prisoner system. One of them was Vasily Vasilevsky, who was responsible for assigning work duties.

Vasilevsky learned that Shtilmark was an experienced writer and came up with a plan that would benefit them both. He would relieve the newcomer of onerous labor and in return the latter would write a historical novel for him. Vasilevsky had heard that Stalin was fond of such books and wanted to send the Soviet leader such a "gift" under his own name in the hope of being amnestied or at least having his term reduced.

Work in the Arctic Circle clearly meant nothing good apart from getting frostbitten fingers in the course of logging work. So, Shtilmark agreed. Vasilevsky sent him to work in the prison bath house and provided him with paper and ink. Shtilmark worked on the book for 20 hours every day for 14 months.

The novel, which describes the adventures of pirates in the waters of the Indian Ocean, North American Indians, the era of great geographical discoveries and the Spanish Inquisition, was written "by the light of a diesel oil lamp, in a desolate earth dwelling in the taiga, without a single page of background information to use as a crib, without glancing at a map or a book", the author wrote to his son. He obtained some information about Old England from a jailed professor who had been abroad.

Shtilmark read each new chapter out to the prisoners, and they waited impatiently for the continuation. In the camp he was treated with new-found respect and nicknamed "Old Man Novel Writer". In his autobiography, A Handful of Light, Shtilmark described how Vasilevsky decided to hire one of the camp's roughnecks to murder his "literary slave" when the novel was almost complete. But Shtilmark had won the respect of the other convicts, and they intervened to protect him.

The fate of 'The Heir from Calcutta'

Robert Shtilmark

Robert Shtilmark

After his release from the gulag in 1953, Shtilmark remained in exile in Siberia for some time. He had already almost forgotten about his novel when a letter from Vasilevsky arrived. The fraudulent author reported that the manuscript had been confiscated, and asked for Shtilmark's son in Moscow to apply to the security services to have it returned - and assist in getting it published. Shtilmark instructed his son, Feliks, to this effect.

As Feliks later wrote in a foreword to his father's autobiography, in the end the manuscript was returned. Security service officials even said that it was a good piece of writing and should definitely be published. Feliks passed the text to a writer of his acquaintance, Ivan Efremov, who was initially skeptical, and, on top of that, the author's labor camp past was a possible obstacle to publication. But having started the book, Efremov could not put it down. "Why isn’t your Fedya (Feliks) not bringing me… the third volume! Send him here as soon as possible. In the family, we are all on edge and really impatient. I can send my son Allan to this Fedya of yours: He was supposed to be going away, but he can't leave without first finding out how things turn out at the end of the novel!" Efremov is quoted in Shtilmark's autobiography as remarking.

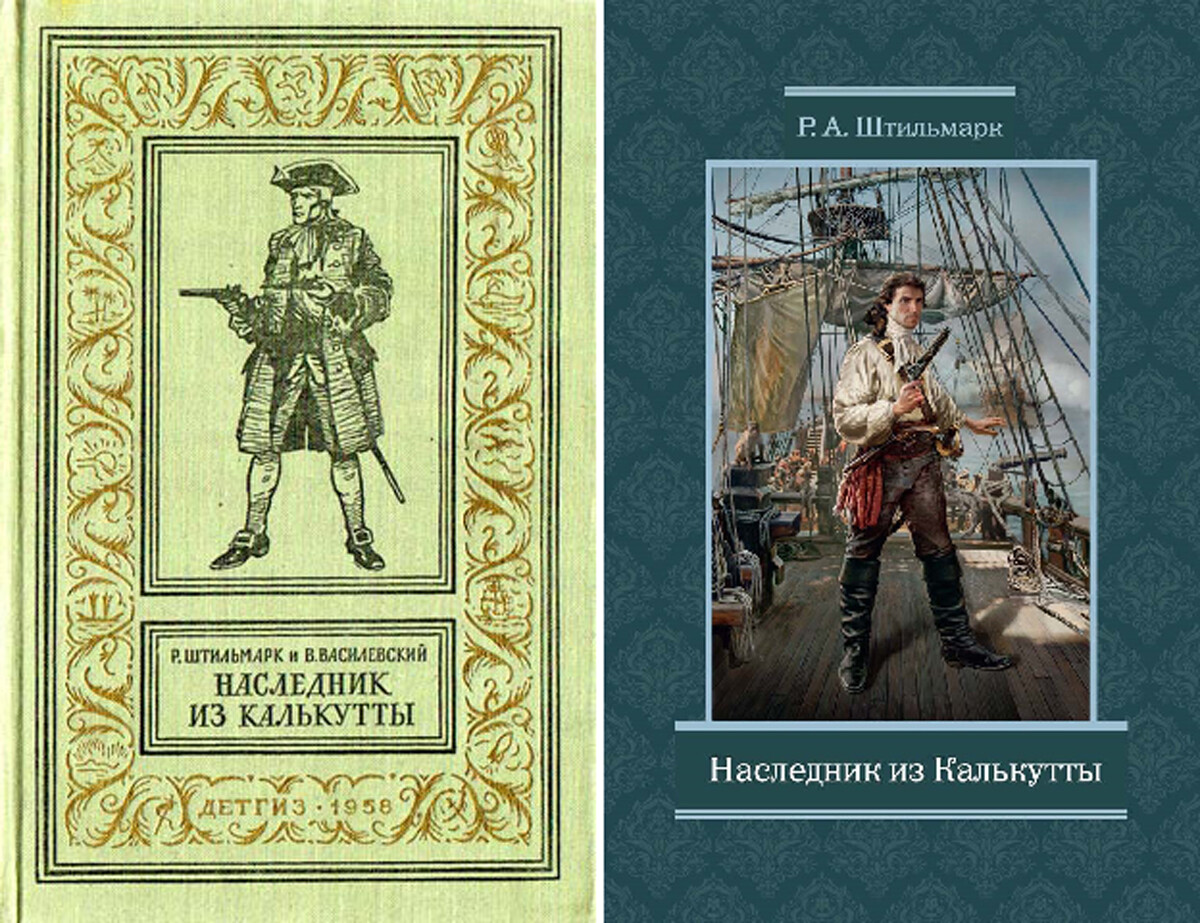

Efremov eventually recommended the book for publication. In 1958, The Heir from Calcutta appeared in print under the names of two authors: R.A. Shtilmark and V.P. Vasilevsky. The publishing house urged the author to remove the imposter's name, but Shtilmark left it in "out of comradely solidarity towards a former camp inmate" and because without him the book would not have come to be written in the first place.

Two names appear on the cover of the first edition - Shtilmark's and Vasilevsky's. The right one is a new edition carrying only one name

Two names appear on the cover of the first edition - Shtilmark's and Vasilevsky's. The right one is a new edition carrying only one name

At this point Vasilevsky demanded that Shtilmark pay him half the royalties and started threatening his "co-author" that his prison friends would get him. Eventually, Shtilmark managed to obtain a court ruling confirming him as the sole author, paying just a small sum to the "author of the idea".

Another improbable detail of the affair came to light. In order to prove his authorship, the "Old Man Novel Writer" had left a coded message in the text of Heir. In one passage, the first letter of alternate words spelled out "bogus writer, thief, plagiarist" - and, of course, the reference was to Vasilevsky.

In 1959, the novel was published under the single name of the real author. It was republished in 1989 during Perestroika, which was a time when many previously banned books became accessible to the public - from Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn to Boris Pasternak. The new wave of interest from the public also derived from the fact that the labor camp origins of Heir had come to light after previously being hushed up for decades.