Why the most dangerous creature in Russia is NOT the bear or the wolf

After a walk in the woods, Viktor Morozov, a resident of Krasnodar, noticed a large red spot under his knee, but paid no attention to it. He thought he must have grazed his leg. A month later, however, he felt strange pressure in his limbs. After two months his legs began to go weak. A few weeks after that he needed a walking stick to get to work. He developed an abnormal sensitivity to light and felt pain from working at his computer screen. He wore dark glasses even in the evening.

After dozens of different tests and examinations, doctors found the cause: Viktor's antibodies to borreliosis (Lyme disease) were 16 times higher than normal. It turned out that six months prior he had been bitten by an infected tick. In that time the disease had become chronic and had affected his nervous system.

Some people in Russia can't figure out for years why their arms and legs have gone weak, their joints ache and their diction has deteriorated - until suspicion falls on a tick.

Meet the tick

Because of its small size, it is easy to mistake a tick for a mole or a speck of dust, or not notice it at all. The male of the most common ixodic tick in Russia can reach 2.5 mm in length and the female 4.5 mm.

Ticks are blood-sucking arachnids. Their usual hosts are wild animals, birds and livestock. But they can also choose humans as victims.

"Contrary to a common misconception, ticks don't fall from trees and don't jump. They hunt from grass or from bushes," says Olga Germant, senior researcher at the Scientific Research Institute of Disinfectology of Rospotrebnadzor (the federal agency for the protection of consumer rights and human well-being). "The tick climbs onto a blade of grass and clings to it with three pairs of legs, and it raises its front legs upwards as if praying. On the tips of its front legs it has a whole mechanism for attaching itself to its victim: a set of hooks and suction pads."

Ticks have no preferences when it comes to their choice of prey - they just react to heat. Once attached to a potential "donor", they crawl up looking for a secluded spot. A person usually has a window of 30 minutes to notice and remove a tick before it attaches itself to their body.

Males suck blood for just a few hours and don't increase in size much. Females can suck blood for several days and swell to 10 mm, drinking 100 times their weight in blood. The bite of a tick is not dangerous, however - ticks are just one of thousands of bloodsuckers on the planet. What is dangerous is the diseases they can carry, some of which can have severe consequences or even lead to a fatal outcome.

Those who lived in the USSR remember that in the past it was possible to walk in the forest without any fear of ticks. Before the beginning of the season of tick activity, forests and fields used to be treated with anti-tick pesticide sprayed from helicopters.

The spraying is done today as well, but another, less effective pesticide is used. In Soviet times ticks were controlled with Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT). The substance proved so effective in eradicating ticks, malaria mosquitoes and other insects that the Swiss chemist Paul Müller received the Nobel Prize in 1948 for the discovery of DDT's properties as an insecticide. It transpired with the passage of years, however, that the toxin accumulates in plants and enters the animal and human food chain. That is why DDT is no longer used in Russia and many other countries.

What are ticks infected with?

Half a million people go to the doctor after a tick attack each year, while almost 1,500 have died from an infected tick in the last 10 years.

Alongside Lyme disease, the most dangerous infection carried by the parasites is tick-borne encephalitis. This is a serious viral disease that attacks the brain and spinal cord. Cases of encephalitis infection are rarer than Lyme disease, but its rarity is made up for by the severity of the disease and its fatality rate (which is one-two percent for the European subtype and 20-25 percent for the Far Eastern one). Its possible effects include paralysis, bad headaches, coma, the risk of hearing or sight loss, and death.

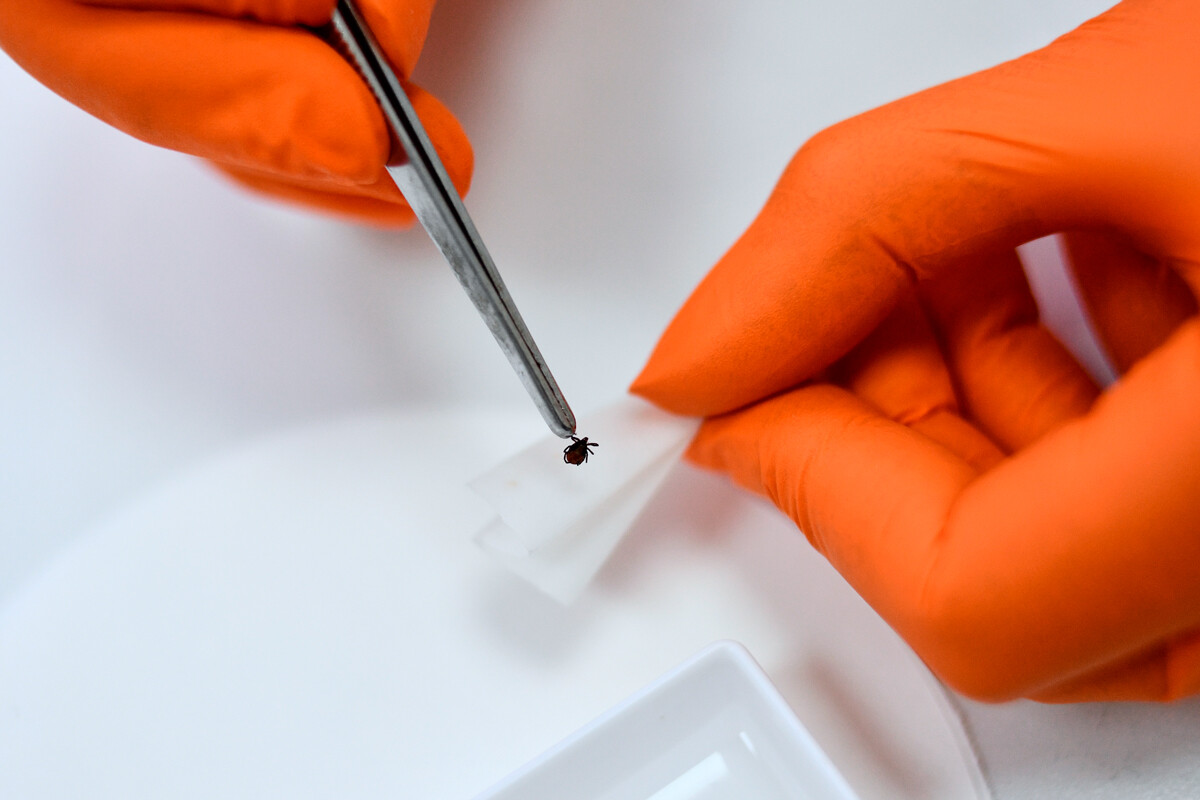

Ixodic ticks carry a total of 300 types of disease agents. And although only a small proportion of these diseases can be passed to humans, some of them are "killers" (for instance Crimean hemorrhagic fever and Siberian tick-borne typhus). What is more, around 20 percent of ticks carry several infections at once, and it is impossible to tell from their external appearance whether they are carriers. That is why the tick has to be brought to a laboratory for testing as soon as possible, and an analysis has to be carried out as rapidly as possible - within a day or two at the most.

When should you get vaccinated?

"I was looking at my photographs from the Krasnoyarsk Pillars national park yesterday, and noticed that there are as many signs warning of bears as there are signs about ticks. My Siberian friends compelled me to get vaccinated before going to visit them," our editor Erwann Pensec says.

Rospotrebnadzor compiles an annual list of danger zones. There are 47 of them currently, and they don't just include the Urals and Siberia with their boundless taiga forests. The list features the Moscow and Leningrad regions in Central Russia, and even St. Petersburg. Ticks can be encountered not just in woods and fields but also at allotments and cemeteries, as well as city parks and squares.

"I personally take my dog for walks in Moscow's Serebryany Bor park on my days off. Despite his wearing an anti-tick collar and being sprayed with a special repellent, I remove something like five loose ticks and a couple embedded in his skin from him after each walk," journalist Pavel Orlov says.

Unlike for Lyme disease, a vaccine for encephalitis does exist. But Russia does not yet have a mass vaccination program against tick-borne encephalitis as it does for flu, for instance.

Ideally, one should get vaccinated six months before traveling to a "danger" region (if the trip is planned for summer, it is best to have the vaccine done during the winter). Or at least six weeks beforehand: The vaccine is administered in two stages with a one-month minimum interval between the first and second jabs, and revaccination a year later. At least two weeks are needed for immunity to set in, so both jabs need to be done at least two weeks before travel to an endemic area. There is already 95 percent protection against the disease after the second injection.

Why you definitely need to take the tick to a lab

A big role in the gloomy statistics for tick-borne diseases is played by people's attitude to these parasites. The residents of large cities are most likely to take a tick to a lab straight away. Paradoxically, in the countryside, and especially in "danger" zones where people remove ticks from their skin several times each summer, they don't get into a panic about it - many people in these places regard them as an everyday occurrence and simply remove the parasites from their skin.

Lyme disease is treated with antibiotics and, if caught at an early stage, can go away without any ill effects. But people frequently go to the doctor with a neglected form of the disease because it can be symptomless for months and even years (which is why it is called the "invisible illness").

Moreover, an expanding red rash only forms at the site of the bite in a certain number of cases. Sometimes the bite leaves no mark at all.

An antibody test doesn't always reveal the presence of the disease, either. With Lyme disease, antibodies are not formed immediately but only in the third or fourth week after a bite (and sometimes later). By that time the infection can already have passed to the internal organs. And 10 percent of infected victims don't form any antibodies at all. That is why doctors warn that it is so important to keep the tick that bit you and bring it to be examined.