New Year’s traditions in the Soviet Union (PHOTOS)

Just imagine: You’re seven years old, and you wake up on a frosty, snowy morning on Dec. 31, open your eyes and find yourself… in the Soviet Union. In the corner stands a decorated New Year’s tree, all covered in silver tinsel "rain", with glass baubles in the form of miniature cosmonauts, a red star and… a corn cob. The tapping sound of a knife on a chopping board comes from the kitchen: Mother has been preparing ingredients for the "main salad" since morning. On the radio, Maya Kristalinskaya is singing her famous "The Snow is Falling". To pass the time until evening, you take your warm woolen socks off the radiator where they’ve been drying and go outside where other kids are making yet another snowman.

That was a typical morning on the last day of the year for children, who were allowed to enjoy all the most carefree moments of the New Year’s holiday. For adults, preparations for the main party of the year started long before the morning of Dec. 31. They would have been going around anxiously trying to organize everything, and it would not have been simple. There were items and rituals without which the Soviet New Year was unimaginable. And this certainly had its own magic.

The first thing people started thinking about was the food for the New Year's Eve dinner. The "hunt" for something special, something "better" (and, given the shortages, "hunt" really did mean "hunt"), began several weeks or even months in advance. A jar of pâté, a tin of pineapple or a bag of chocolates could stand untouched in the farthest corner of the fridge for a long time. "That's for New Year's Eve!" was the phrase used every day to unceremoniously keep everyone away from the holiday food until zero hour arrived.

In Soviet times, many people put up a real New Year’s tree at home. Thus, several days before the event, they would go to a special holiday tree market or look for a suitable spruce in the woods, which was also par for the course at the time.

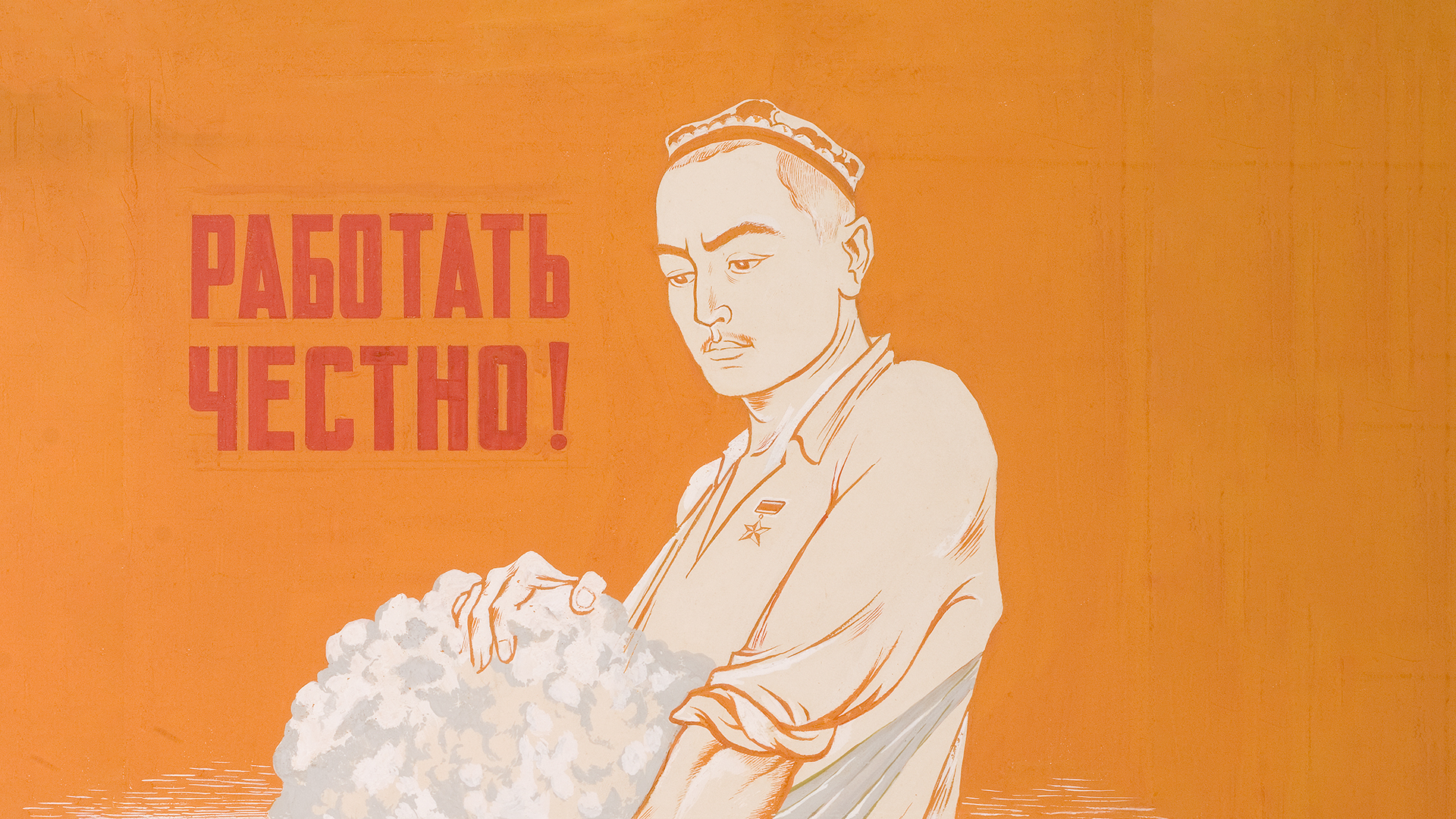

The entire family usually decorated the tree together. Most decorations were passed down in the family or were homemade. By tradition, children were taught how to make them during handicraft lessons at school. Many New Year’s decorations were themed, depending on what was popular at a particular time in Soviet society - for instance, space or the agricultural industry - and hence decorations could be in the form of corn cobs, apples or carrots, or there could be New Year’s baubles with portraits of Soviet leaders.

Not long before the New Year, everyone would unfailingly take their children to a New Year’s fair, to the Detsky Mir children's store or to GUM (the Main Department Store on Red Square). And even if people had no money to buy anything, they still went in search of a "New Year’s atmosphere" - these locations were very lavishly decorated in order to inspire the holiday spirit.

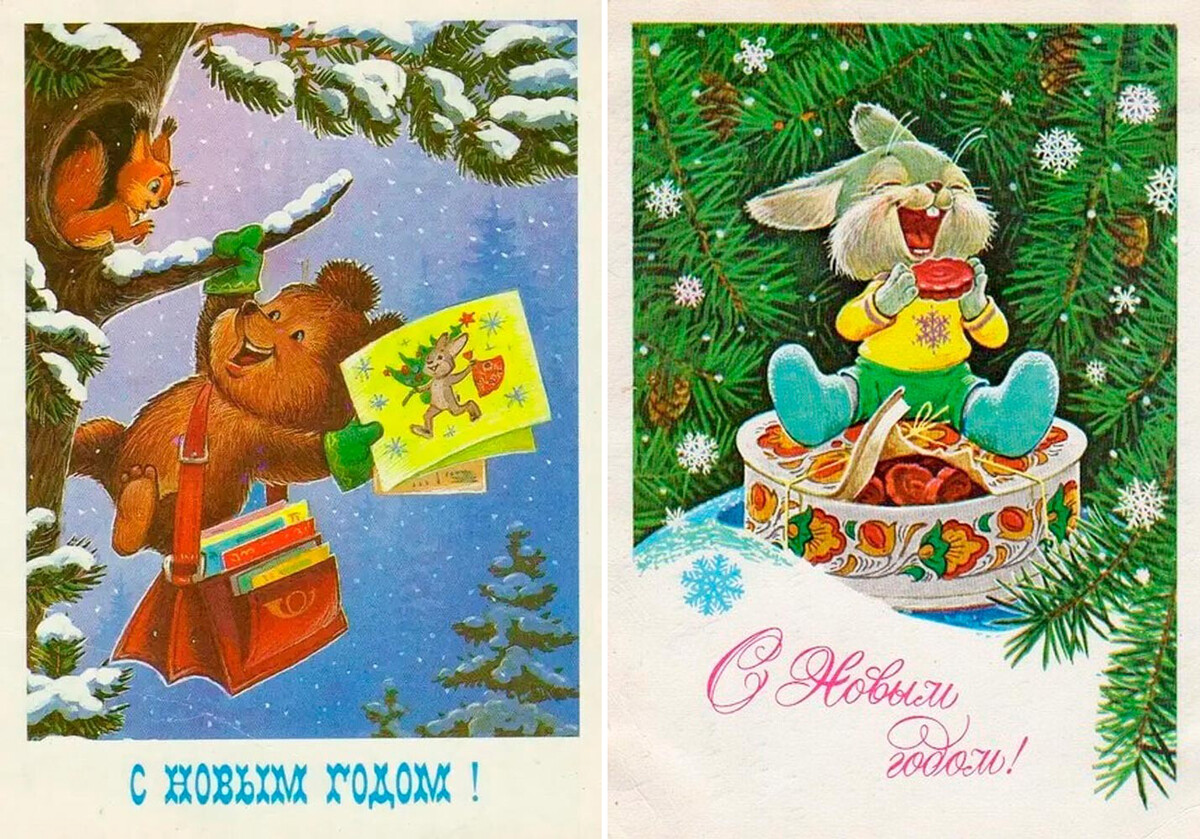

Presents were prepared well in advance, even though Soviet people did not have much of a choice; even a jar of home-made cucumbers or a stick of cured sausage were popular options. Sometimes, greetings were simply conveyed via a New Year’s card: The classic Soviet cards depicted cute animals in snowy forests.

New Year’s fancy-dress parties presided over by Grandfather Frost (the Russian version of Santa Claus) and Snegurochka (his grand-daughter, the Snow Maiden) were eagerly anticipated. These took place throughout the week of the New Year. Each town had a central New Year’s tree that would stand in a cultural center or theater, to which adults would desperately try to obtain tickets for their children (the most exclusive and grand New Year’s tree event and fancy-dress party was at the Kremlin Palace in Moscow).

Those who did not manage to get into such grand events still went to a fancy-dress party, but a more modest one. A party was held in every kindergarten and school.

New Year's costumes were sewn at home. Boys would usually dress as hares or bears, and the girls as snowflakes, foxes or squirrels.

Women would spend the entire morning and afternoon of New Year's Eve preparing the holiday dinner: The USSR had several classic New Year’s dishes, and everyone did their best to make at least some of them. Olivier salad, crab salad, "herring under a fur coat" and red caviar canapés (in the good times) made up the ideal New Year's menu.

While the food was being prepared, the TV would be on in the background and people would watch Soviet New Year's comedies, which put viewers in a holiday mood even though they already knew what was going to happen because the same films were screened every year. The main movie was "Irony of Fate" (1975), in which on New Year's Eve, after a wild time in the banya, the protagonist, Evgeny Lukashin, finds himself in Leningrad instead of his hometown of Moscow.

After this film became popular many Soviet men adopted the tradition of going to the banya with friends on Dec. 31 - to give themselves a good scrub before seeing in the New Year.

In the evening the whole family would gather at the festive table. New Year’s in the Soviet Union, like Christmas in the West, was a family celebration. It was also important to visit relatives on that day and express good wishes for the rest of the year.

From 1970 onwards, at five minutes to midnight, Soviet television showed the head of state's address to the nation, which every family watched from their dinner table. At first it was more like an annual summary of the year's accomplishments, but from Mikhail Gorbachev onwards it took the form of New Year’s greetings.

After that, the TV showed the clock on the Kremlin's Spasskaya Tower striking 12 times to usher in the New Year. And while the chimes were ringing out, everyone made a wish. By tradition, it had to be written on a scrap of paper, burnt over a candle, and the ash then put in a glass of sparkling wine that had to be drunk before the last stroke of midnight. To be fair, not everyone accomplished this ritual, but it was still important to open a bottle of sparkling wine and fill everyone's glass before the last of the 12 chimes had rung out.

The "official part" was followed by the real revelry. Many families dined, chatted and danced to Little Blue Light - the first entertainment show on Soviet TV which had celebrities and ordinary people narrating anecdotes and stories, talking about "this, that and the other" and wishing each other a Happy New Year. One of the first guests on the program was the first man in space, Yury Gagarin. The show still goes out to this day, but only at New Year’s, in tribute to the Soviet tradition.