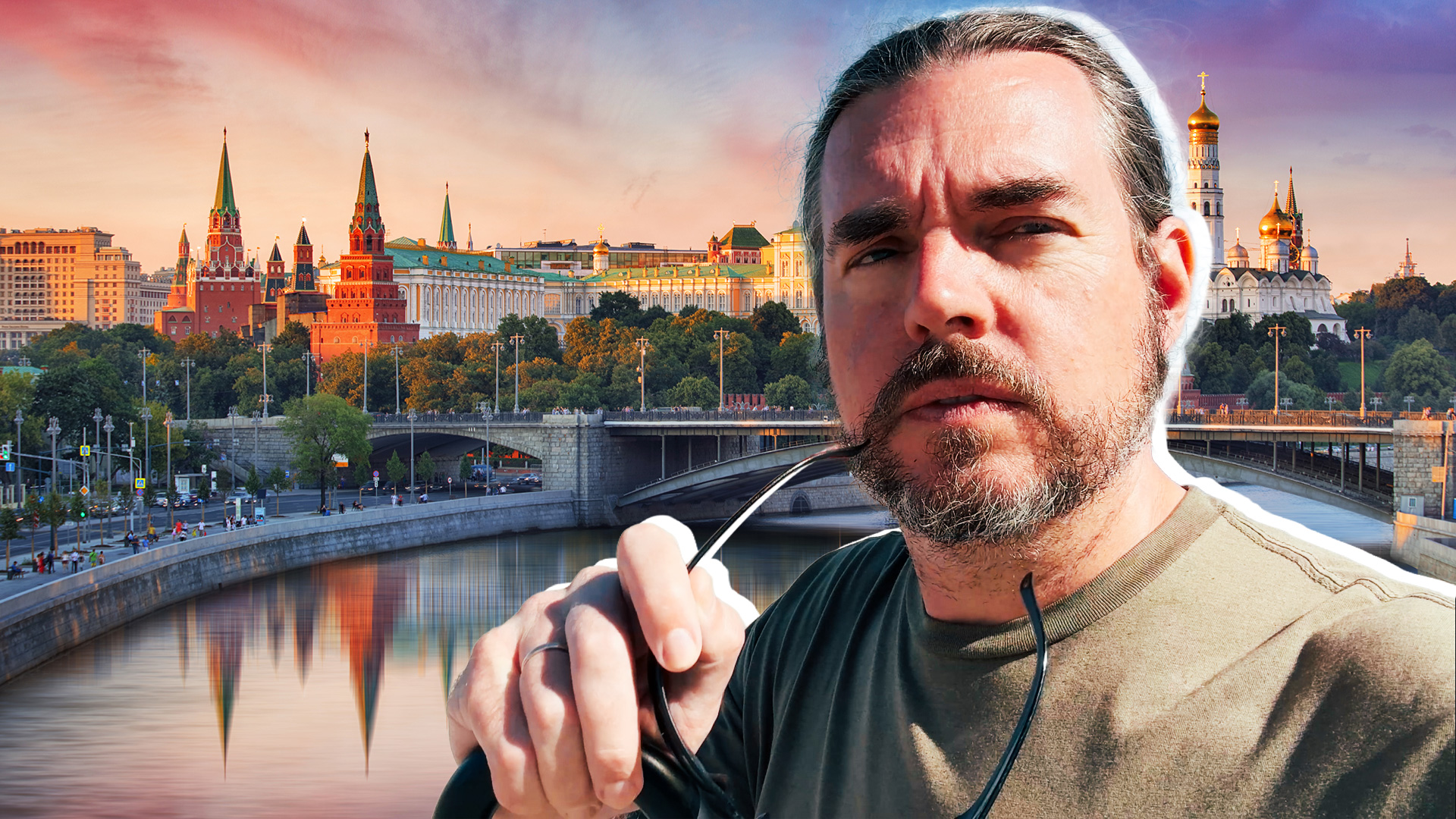

What’s so special about the Russian DEDUSHKA? (PHOTOS)

“I would be overjoyed if you could write a piece on [the] Dedushka!!!” This is a request we received from a reader after he spotted our article on the phenomenon of the Russian ‘babushka’. Well, our readers’ word is gospel. So, without further delay, here it is!

Who is a ‘dedushka’?

Pensioners with the Soviet flag and portrait of ‘dedushka’ Lenin, which was how the revolutionary leader used to be called in the late Soviet era

Pensioners with the Soviet flag and portrait of ‘dedushka’ Lenin, which was how the revolutionary leader used to be called in the late Soviet era

The Russian word ‘dedushka’ literally translates as granddad (or grandpa). ‘Dedushka’ has origins in the word ‘ded’, which, in Russian language, is an official definition for grandfather. A wider meaning of the word ‘ded’ is an old man, synonym of the word ‘starik’ (old-timer).

The diminutive ‘dedushka’ has become a more common way for grandchildren to address their grandfather, especially if they are still small kids. While speaking of a grandfather, an adult would rather say ‘ded’.

The Russian Santa, aka Ded Moroz

The Russian Santa, aka Ded Moroz

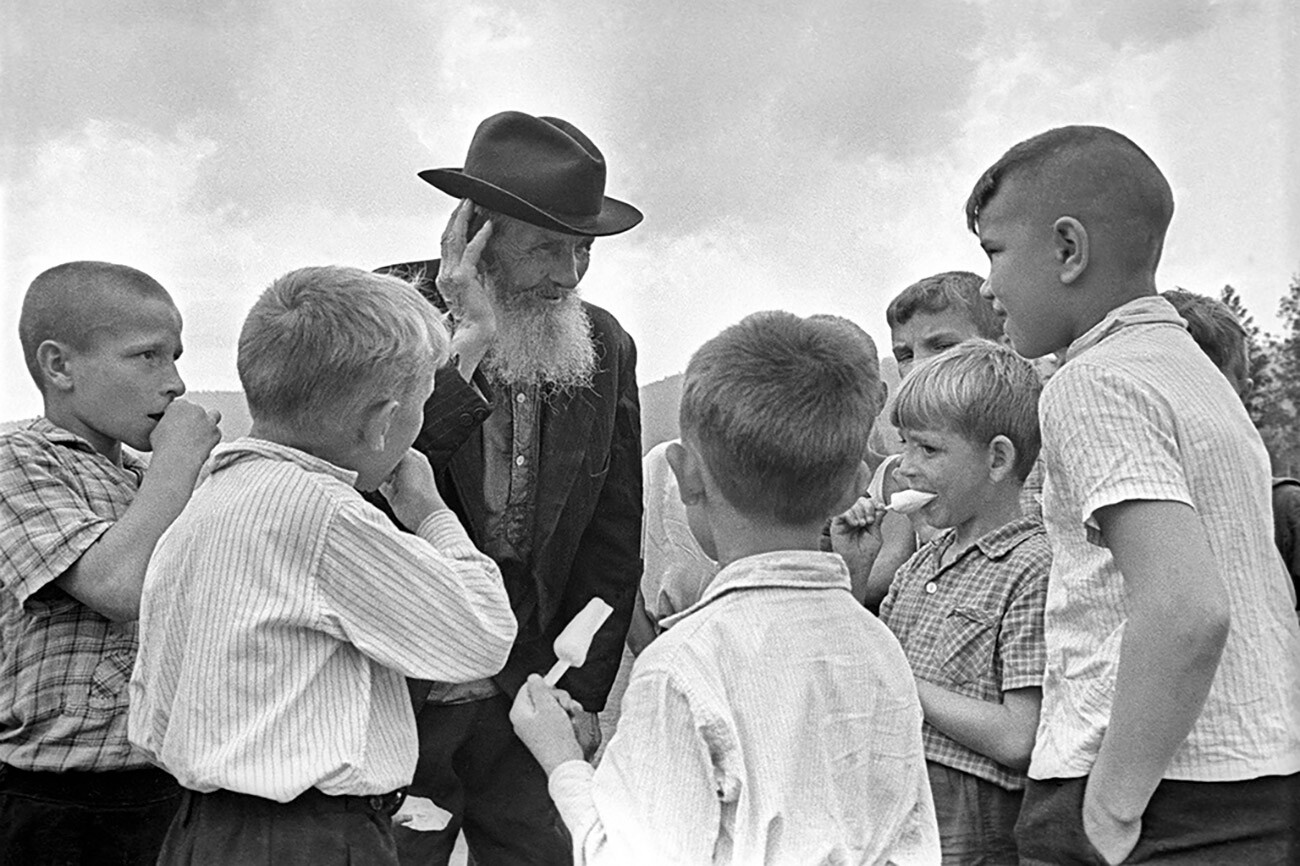

You may also know about Ded Moroz, literally ‘Grandfather Frost’, who is a Russian Santa Claus. And a Russian ded is actually a very frequent hero of folk fairy tales. He’s usually a kind, old man that is raising a granddaughter alone. Or a kind, old wizard. Or a poor, old man that is being abused by his grumpy wife.

Tough from the outside and soft inside

Most of the modern dedushkas grew up in the Soviet Union, where kids were raised in typical gender role traditions. Women should be keeping the hearthstone, cooking and taking care of kids, while men are breadwinners who would work a lot (frankly speaking, women also worked, but their main role was considered to be the role of housewife at the same time). So, no surprise, that babushkas enjoy taking care of kids, while dedushkas… not so much.

Dedushkas like fishing

Dedushkas like fishing

“I remember my dedushka didn’t talk to me much. I think going to their house in the country in summer, I just annoyed him by forcibly changing his usual routine (and taking away all of babushka’s time and attention),” Sergei, 63, recalls.

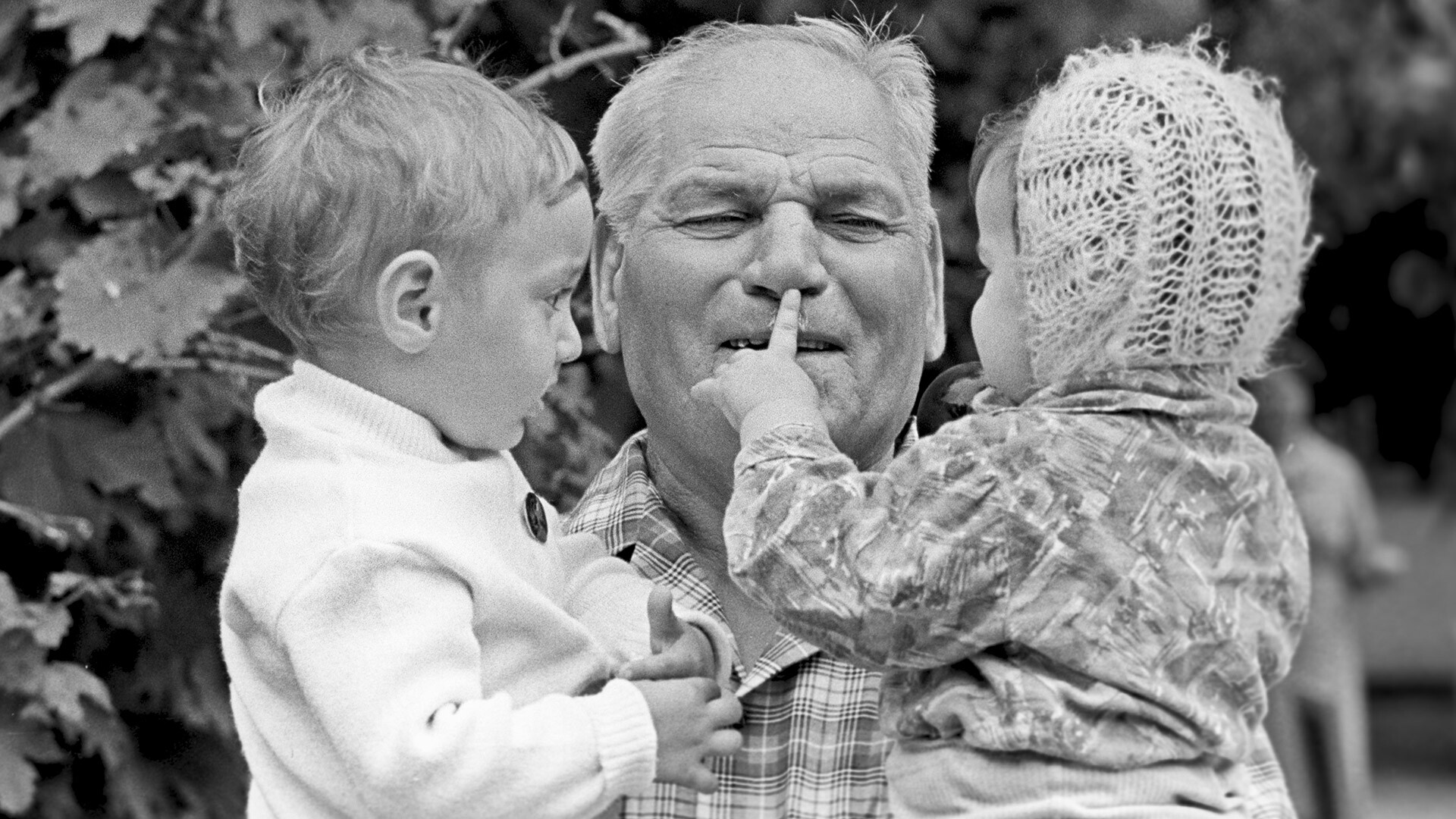

A Russian ded is also a hero of anecdotes and tales. Usually, he is annoyed by “those loud kids” (and by the level of care that his wife usually gives them). A dedushka usually hates all the baby talk, coddling and lispering. A ded can only afford to show some tenderness when the kid is still a newborn baby or very small toddler. But after that, there should be ORDER in the house and the ded is always aware of not spoiling a grandkid too much.

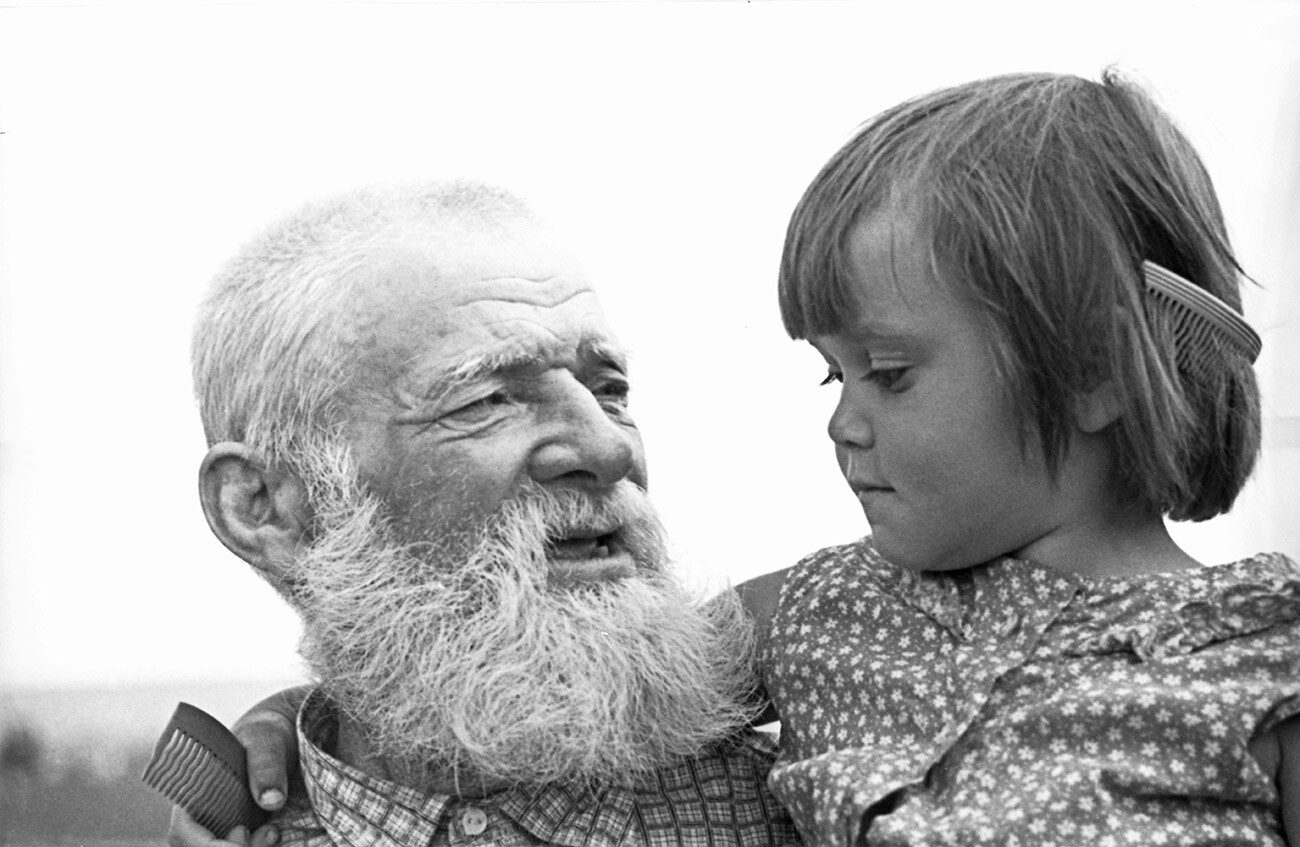

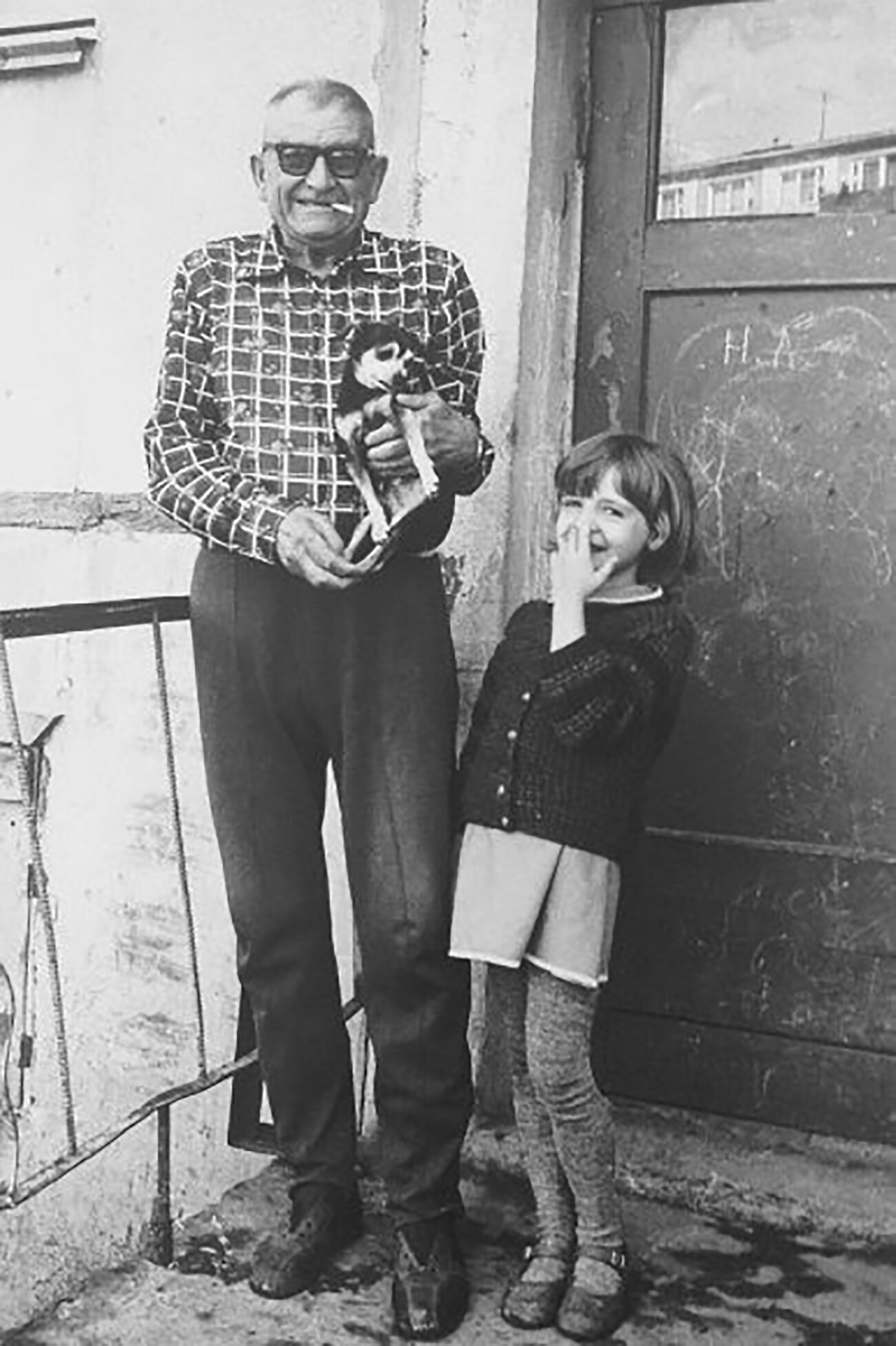

A dedushka will only show affection to a small kid or a girl

A dedushka will only show affection to a small kid or a girl

Most Russians would recall their dedushka smoking a cigarette in silence, fishing or picking mushrooms alone. “My grandfather used to read the newspaper every single morning and, while reading, he wouldn’t pay any attention to me, even if I would stand on my head,” Katya, 32, recalls.

And despite that, many dedushkas went through World War II or other tough societal changes during Soviet history, they didn’t like to recall them or tell the tale. They would rather mutely drink a shot of vodka on Victory Day, commemorating everyone who has passed away.

Dedushka would always wear all his medals and orders when celebrating Victory Day

Dedushka would always wear all his medals and orders when celebrating Victory Day

However, despite looking incredibly tough, a dedushka usually has a kind heart. “That’s weird, a dedushka has never indulged me, but when it came down to babushka potentially punishing me for something, he always took my side and protected me,” Olga, 50, says. “And, when I was already a teenager, I went out until late and babushka would worry and ask to come home earlier, but dedushka always told her to let me have fun!”

A babushka and dedushka together are the most sturdy union

A babushka and dedushka together are the most sturdy union

It is also surprising that looking that tough, the dedushka always had some enormous love for babushka (which he, for sure, never showed in public). And that is why we often hear that when babushka passes away earlier than dedushka, he literally dies from sorrow and sadness a short while after her.

Dedushka’s vision of love

The babushka usually spreads the absolute, unconditional love to her grandchild, constantly feeding them, being tender, checking on how well they are dressed so as to not catch a cold. (By the way, because of this, all Russians have a phobia of sitting on cold surfaces, especially stone, and are afraid of catching a cold from drafts. Because that’s what babushka always used to say!

At the Spartak Moscow soccer stadium with dedushka

At the Spartak Moscow soccer stadium with dedushka

A dedushka is different. The thing is that, throughout history, men in Russia knew no warm relation, no tenderness. One of the most colorful and authentic descriptions of a ded in Russian literature can be read in Maxim Gorky’s autobiographical novel ‘My Childhood’. There is a common Russian ded, the head of a big family that is in charge of the order in the house. He is a wise and a very principled man and, to teach his grandkids to behave better, he beats them… for every single wrongdoing.

And, the thing is that this is how dedushkas used to show their love - they wanted their grandchildren to grow up principled people who could be in charge of their life and behavior.

Of course, times have changed; but, many modern dedushka still grew up in Soviet times and still see nothing wrong in a small smack upside the head… for a preventive purpose, of course. Not because they are awful abusers, but because that’s how generations of Russian men were raised. No hugs, but small smacks.

A dedushka is more willing to listen to your problems and suggest solutions

A dedushka is more willing to listen to your problems and suggest solutions

The very modern dedushka, remembering their role of breadwinners, used to show their love with money. If the babushka is worrying if a kid eats well and turns on a headwear in winter (no matter what age the KID is), the dedushka is more about supporting, whether moral or financial. He asks if everything is fine, gives advice if needed and often offers extra pocket money, so that a kid feels more comfortable (“but don’t tell babushka!”).

Why do we speak less about dedushka than about babushka?

Women in Russia, on average, live longer than men and statistics say there are simply more babushkas than dedushkas. In 2021, the average male life expectancy in Russia was around 65, while, for women, it was closer to 74 (and these numbers have been more or less the same since the 1990s).

At the same time, during the brutal 20th century, loads of Russian men died during several wars and purges. And millions of women were left alone to make a living, keep a household, as well as raise kids (and grandchildren).

With dedushka you could always giggle (about babushka, too)

With dedushka you could always giggle (about babushka, too)

Lots of families in the post-Soviet space have never seen their dedushkas, as many died in World War II. That’s why the memory of this war is still so strong in Russia. Or, having poor health after years of hard work (as well as some time spent in the Gulag), dedushkas would pass away too young.

“Those who no longer had a dedushka always felt envy for those who had. We thought that meant that there is a real man in the house,” Sergei adds. “I was lucky to have a neighbor’s ded, who taught me how to chop firewood and took me fishing (but always asked not to chat too much!).”