Exploring Kargopol: Treasure of the Russian North

Kargopol. Cathedral Square, northeast view. From left: Bell tower, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Church of the Presentation. July 28, 1998

Kargopol. Cathedral Square, northeast view. From left: Bell tower, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Church of the Presentation. July 28, 1998

At the beginning of the 20th century, Russian chemist and photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography. Inspired to use this new method to record the diversity of the Russian Empire, he photographed numerous historic sites during the decade before the abdication of Tsar Nicholas II in 1917.

Transfiguration Monastery

Among the most remote places photographed was the Solovetsky Transfiguration Monastery, located on Great Solovetsky Island, part of an archipelago in the southwestern part of the White Sea. As the Great War raged in Europe, Prokudin-Gorsky visited Solovki in the Summer of 1916 and took 20 photographs at or near the monastery.

Solovetsky Transfiguration Monastery. East wall with Archangel Tower, Cooks Tower & Kvas Brewing Tower (right). Summer 1916

Solovetsky Transfiguration Monastery. East wall with Archangel Tower, Cooks Tower & Kvas Brewing Tower (right). Summer 1916

Founded in the 1430s by the monks Zosima and Savvaty, the Transfiguration Monastery flourished in the mid-16th century under the guidance of hegumen Philip (Feodor Kolychev), a Muscovite monk of noble origins, when the great Cathedral of the Transfiguration was built.

His public resistance to actions by Ivan IV during the late 1560s led to the prelate’s exile and death in 1569. Despite this tragedy, intensive development at the Solovetsky Monastery continued throughout the late 16th-century with the construction of additional churches and monastic buildings.

Trading post

Kargopol. Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, view from bell tower. Background: Lake Lacha & Onega River. June 15, 1998

Kargopol. Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, view from bell tower. Background: Lake Lacha & Onega River. June 15, 1998

During the same period and in the same area, the town of Kargopol, located on the Onega River in the southwestern part of Arkhangelsk Province, also flourished, primarily through the salt trade that linked it to the Solovetsky Transfiguration Monastery. Despite the town’s small size (now under 9,000 residents), the majesty of its central cathedral ensemble is testimony to its importance in bygone times.

To this day, there is disagreement on when Kargopol was founded and what its name means. Yet, it is considered one of the oldest northern settlements, founded perhaps as early as the 11th century.

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, northeast view. February 27, 1998

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, northeast view. February 27, 1998

The town’s favorable location, near Lake Lacha and the origins of the Onega River, attracted the attention of neighboring principalities such as Belozersk and Vologda, as well as Novgorod, which exercised overall authority in the area during the early medieval period.

Kargopol’s beginnings

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ. Interior, view east toward icon screen. August 12, 2014

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ. Interior, view east toward icon screen. August 12, 2014

The earliest historical reference to Kargopol is a mention of its prince Gleb, who fought under Grand Prince Dmitri during Moscow’s victorious struggle against the Mongols in 1380. Subsequent references to the town occur sparsely in mid-15th century documents.

With Moscow's subjugation of Novgorod at the end of the 15th century, the Kargopol lands came into the domains of Ivan III. By the 1560s, the town had become an important center in the realm of Ivan IV (the Terrible), who granted Kargopol lucrative, much-coveted privileges for the production of salt.

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ. Icon screen, Royal Gate (entrance to main altar space). August 13, 2014

Cathedral of Nativity of Christ. Icon screen, Royal Gate (entrance to main altar space). August 13, 2014

The trading routes along the Onega River to the White Sea have long since lost their significance and salt is no longer the region’s major commodity. Yet, Kargopol's remarkable white stone churches remind of its former wealth. And its dimensions are much the same now as they were four or five centuries ago.

Cathedral of Catherine the Great

Cathedral Square, northeast view with frozen sunset. From left: Bell tower, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Church of the Presentation. November 25, 1999

Cathedral Square, northeast view with frozen sunset. From left: Bell tower, Cathedral of Nativity of Christ, Church of the Presentation. November 25, 1999

In 1765, a fire leveled much of the town and severely damaged even its masonry churches. The town was rebuilt according to a regular grid plan promulgated during the reign of Catherine the Great. The construction of log houses was prohibited in the immediate vicinity of churches, both for reasons of fire safety and to allow a clearer view of the white stone churches, which unfold in stately progression along the wide Onega River.

Cathedral Square. Church of Nativity of John the Baptist, southeast view. February 27, 1998

Cathedral Square. Church of Nativity of John the Baptist, southeast view. February 27, 1998

At the midpoint of that plan, near the Onega River, is the town's oldest and most important architectural monument, the Cathedral of the Nativity of Christ, begun in 1552 and completed 10 years later. Among its distinctive features is the extensive use of locally quarried limestone for the basic structure.

Cathedral Square. Church of the Presentation, southwest view. Background: Church of Nativity of John the Baptist, cathedral bell tower. July 1, 1999

Cathedral Square. Church of the Presentation, southwest view. Background: Church of Nativity of John the Baptist, cathedral bell tower. July 1, 1999

In its essence, the cathedral design probably derives from Novgorod, which retained much influence over major church architecture in the north during the 16th century. The basic plan is composed of a ground-level space that contained the structure’s foundation vaults and had three altars for services during the long winters. The soaring upper structure was used for worship during the summer.

Changing appearances

Church of the Resurrection (late 17th century), north view. June 16, 1998

Church of the Resurrection (late 17th century), north view. June 16, 1998

The cathedral’s appearance has changed much since the 16th century. In 1652, the ornamental chapel of Saints Philip and Alexis was attached to the north facade, with a raised porch and flanking staircases. Shortly thereafter, a similar chapel, dedicated to the Most Merciful Savior, was added to the south façade.

Church of the Annunciation, northeast view. Built of local limestone on Old Trading Square in 1692-1729. July 28, 1998

Church of the Annunciation, northeast view. Built of local limestone on Old Trading Square in 1692-1729. July 28, 1998

A large porch and staircase were built at the main entrance on the west facade. Although these additions provided decorative variety, they also obscured the main structure, which, over the centuries, has sunk into the ground to a depth of at least a meter, as the earth around it accumulated.

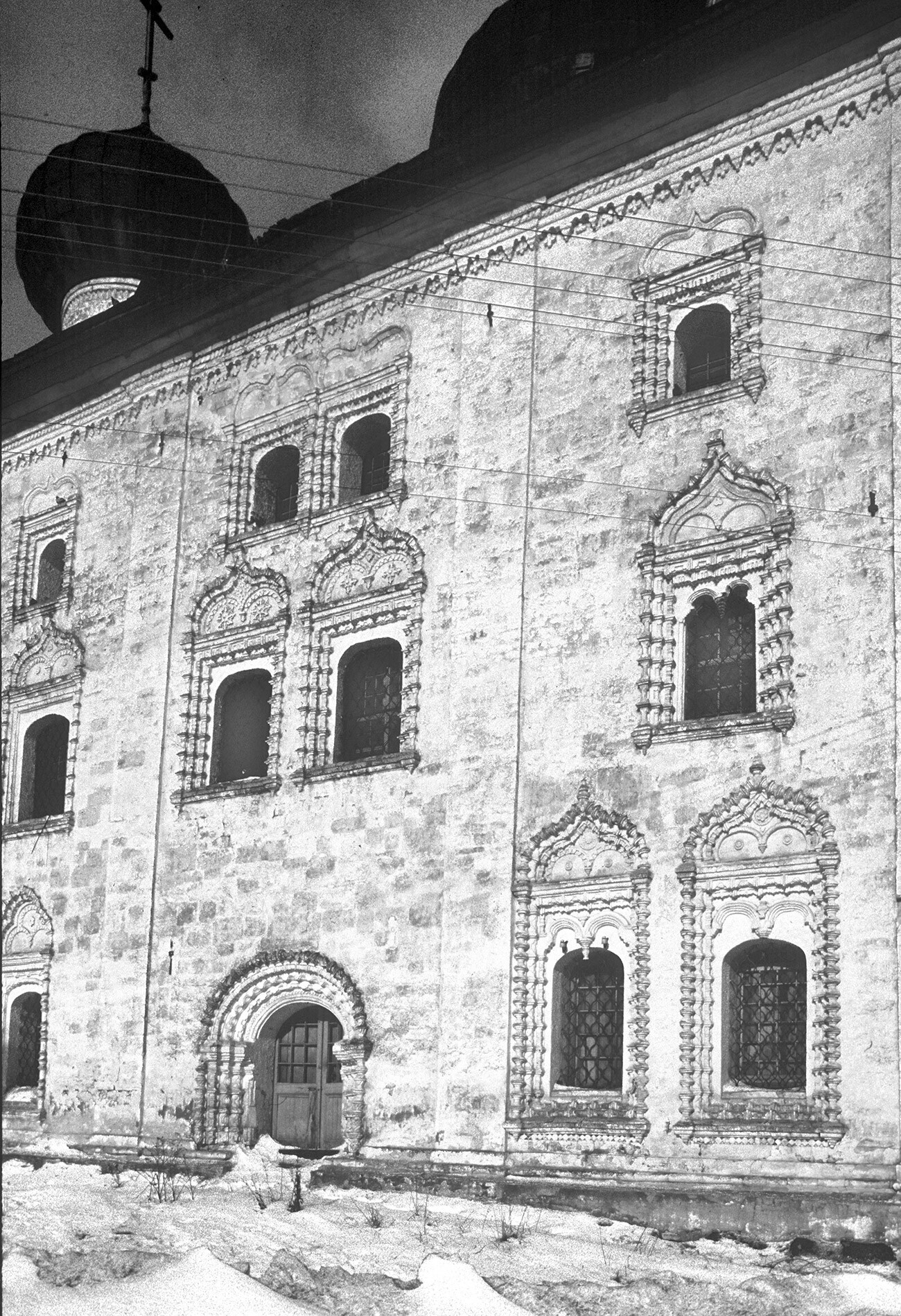

Church of the Annunciation, south facade with decorative limestone carving. March 1, 1998

Church of the Annunciation, south facade with decorative limestone carving. March 1, 1998

The severity of the 1765 fire caused cracks to appear in the Nativity Cathedral walls. Fortunately, authorities decided to preserve the cathedral and reinforced the walls with large bulwarks at the corners. As a result, the imposing white structure, with its five cupolas, seems encumbered on all sides.

Elaborate interior detailing

Church of St. Nicholas (1741), east view. July 28, 1998

Church of St. Nicholas (1741), east view. July 28, 1998

On the cathedral interior, the fire caused great damage to the frescoes that had covered the walls. Those paintings that survived the flames and smoke succumbed to the elements, as the church roof remained unrepaired for five years (The cupolas, made partly of wood, burned in the fire). The interior walls are now covered in whitewash and only a small patch of the original frescoes is preserved on the west wall.

Church of Nativity of the Virgin, north view with attached Chapel of Saints Stephen & Andrew Stratelates. Built of local limestone on Old Trading Square in 1678-82; bell tower added in 1844. June 16, 1998

Church of Nativity of the Virgin, north view with attached Chapel of Saints Stephen & Andrew Stratelates. Built of local limestone on Old Trading Square in 1678-82; bell tower added in 1844. June 16, 1998

The dominant feature of the soaring space is the magnificent wooden icon screen, carved and brightly painted as part of the restoration of the cathedral in the late 18th century. Following church traditions, the screen is placed before the main altar in the east. It ascends in five tiers of icons, from the Local Row to the Festival and Deesis Rows, with Christ Enthroned at the center. The iconostasis culminates in the Prophets Row and the tall icons of the Patriarchs Row. At the top is a large painted crucifix.

Church of Solovetsky Saints Zosima & Savvaty (1819), southwest view. November 25, 1999

Church of Solovetsky Saints Zosima & Savvaty (1819), southwest view. November 25, 1999

The entrance to the main altar is through the elaborately decorated Royal Gate at the center of the Local Row, which also contained a venerated 16th-century icon of the Nativity (now at the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg). It seems miraculous that this astounding array of icons, almost all vividly painted in the late 18th century, has survived in place.

‘New Marketplace’

Konstantin Serkov house (late 19th century), Leningrad Street 10. August 9, 2010

Konstantin Serkov house (late 19th century), Leningrad Street 10. August 9, 2010

With the redesign of the town plan after the fire, the area around the cathedral was cleared to form the so-called New Marketplace, bounded in the northeast by the Church of the Nativity of John the Baptist, built before the fire between 1740 and 1751. Although austerely simple in form, this church with its extended baroque cupolas soars above the surrounding landscape.

Administrative building (19th century), Victory Street 12. August 9, 2010

Administrative building (19th century), Victory Street 12. August 9, 2010

The centerpiece of the New Marketplace ensemble (also referred to as Cathedral Square) is a monumental three-storied bell tower. The impetus for the tower was provided in 1767 by Iakov Sivers, the Governor General of Novgorod Province, as a dominant element in the revival of the town after the devastating fire.

Wooden house (19th century), corner of October Prospect & Victory Street. August 12, 2014

Wooden house (19th century), corner of October Prospect & Victory Street. August 12, 2014

With its mixture of baroque and neoclassical elements, the bell tower was approved by the town as a monument in honor of Catherine the Great, although the empress never visited Kargopol. Because of difficulties in obtaining building materials for such a large edifice, construction of the tower lasted from 1772 to 1778. Its completion endowed Kargopol with a point of orientation not only for the town's main streets, but also from the Onega River.

Andreas Vager house (19th century), October Prospect 29. Note lower plank siding removed to reveal basic log structure. August 9, 2010

Andreas Vager house (19th century), October Prospect 29. Note lower plank siding removed to reveal basic log structure. August 9, 2010

Preserving the past

Wooden house with decorative window frames (late 19th century), Factory Street 3. February 27, 1998

Wooden house with decorative window frames (late 19th century), Factory Street 3. February 27, 1998

The northwest part of the Cathedral Square is occupied by the Church of the Presentation of the Virgin, built in 1802-1808 in a severe, archaic style that complements the other churches of this central architectural ensemble. The church is now used as a gallery displaying traditional crafts and the work of contemporary Kargopol artists.

Mokeev house (late 19th century), October Prospect 43. June 15, 1998

Mokeev house (late 19th century), October Prospect 43. June 15, 1998

Beyond Cathedral Square, Kargopol has preserved several neighborhood churches from the 17th century through the early 19th century, as well as 19th-century houses of wood and brick. All of these architectural monuments reflect times past, when Kargopol was a center of commerce in the historic Russian North.

Aleksei Ushakov house (late 19th century), Leningrad Street 11. August 9, 2010

Aleksei Ushakov house (late 19th century), Leningrad Street 11. August 9, 2010

In the early 20th century, Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916, he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he left Russia and ultimately resettled in France where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the Library of Congress. In the early 21st century, the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the global public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Over a period of work in Russia beginning in 1970, Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Brumfield decades later.