Spiritual Quest: Tolstoy’s visits to the Optina Pustyn Monastery

Optina Pustyn (near Kozelsk). Monastery of the Presentation, northwest view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn (near Kozelsk). Monastery of the Presentation, northwest view. August 23, 2014

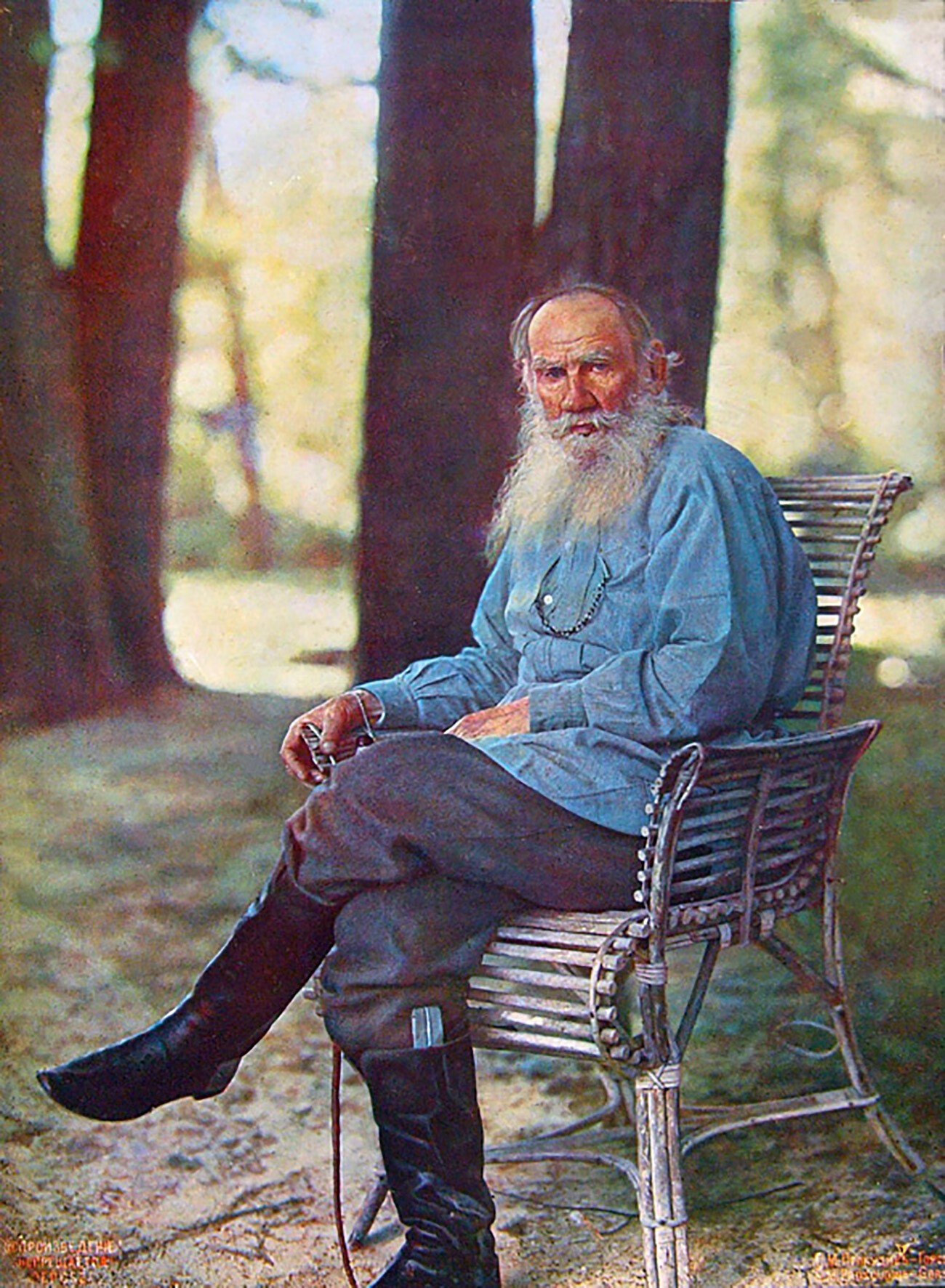

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Russian chemist and photographer, Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, developed a complex process for vivid, detailed color photography. His vision of photography as a form of education and enlightenment was demonstrated through his photographs of historic sites throughout the Russian heartland.Among Prokudin-Gorsky’s most famous photographs is a color portrait of Leo Tolstoy taken in May 1908 at his Yasnaya Polyana estate. This is one of several photographs that he took in anticipation of the great writer’s 80th birthday.

Yasnaya Polyana. Portrait of Leo Tolstoy in his study. Monochrome contact print from original glass negative (not preserved). May 23, 1908

Yasnaya Polyana. Portrait of Leo Tolstoy in his study. Monochrome contact print from original glass negative (not preserved). May 23, 1908

For Prokudin-Gorsky, as for so many other Russians, Tolstoy’s presence at Yasnaya Polyana served as a beacon of justice at a time of immense challenges for the Russian Empire. And while his work brought joy and wisdom to the lives of millions of readers throughout the world, his final years were a time of personal turmoil and alienation from his devoted wife, Sonya (formal name: Sofya, or Sophia, Andreevna).

Writer with a tortured soul

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Holy Gate, south view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Holy Gate, south view. August 23, 2014

In his latter years, Tolstoy became increasingly distraught by what he felt was a lack of sympathy for his social and moral views on the part of Sonya, who deeply loved him, had borne him 13 children (eight of whom lived to adulthood), and had dedicated her life to his work and well-being.

This tragic antagonism was inflamed by some of Tolstoy's closest associates, who advocated a public gesture such as leaving Yasnaya Polyana. The most prominent among these associates was Vladimir Chertkov, a controversial figure who gained Tolstoy's trust and engaged in tireless organizational activity to promulgate the writer's late work and teachings.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Cathedral of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary, east view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Cathedral of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary, east view. August 23, 2014

Adding to the tension was Tolstoy's very public criticism of the Orthodox Church and his rejection of certain basic tenets of the faith. In response, the Church excommunicated him in 1901.

Some have claimed that Tolstoy sought a return toward the end, yet he died unreconciled with the church. There were moments, however, in which he demonstrated an impulse to engage with the church on an intellectual and even spiritual level. A crucial element in these encounters was the nearby Optina Pustyn Monastery of the Presentation of the Virgin Mary in the Temple, a renowned spiritual center that also played an important role in Fyodor Dostoevsky's life.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of St. Mary of Egypt & St. Anne, southeast view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of St. Mary of Egypt & St. Anne, southeast view. August 23, 2014

In the early hours of October 28, 1910, Tolstoy arose after a sleepless night, bade farewell to his daughter Alexandra (Sasha), and departed Yasnaya Polyana with his personal physician, Dushan Makovitsky. Fearing discovery, they traversed a difficult path to the small station of Shchekino, where they boarded a train to Kozelsk Station, some 140 km to the west. After sending telegrams to Tolstoy’s daughter, Sasha, and to Chertkov, they covered the short distance from Kozelsk to Optina Pustyn.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Vladimir Icon of the Virgin. Early 19th-century church demolished in Soviet period, rebuilt in late 1980s with early 21st-century wall paintings by monastery icon painters. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Vladimir Icon of the Virgin. Early 19th-century church demolished in Soviet period, rebuilt in late 1980s with early 21st-century wall paintings by monastery icon painters. August 23, 2014

Tolstoy was no stranger to the monastery: three times between 1877 and 1890 he had met with Father (starets) Ambrose, considered the prototype for Father Zosima in Dostoevsky’s final novel, The Brothers Karamazov. Indeed, many 19th-century writers and intellectuals were drawn to the Presentation Monastery.

A deeply revered monastery with medieval roots

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, northwest view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, northwest view. August 23, 2014

Located in prosperous Kaluga Province, Optina Pustyn is among the most venerated of Russian spiritual sites. Part of the appeal is its favored natural setting in a majestic pine forest overlooking the small Zhizdra River near the town of Kozelsk (some 250 km southwest of Moscow).

Popular legend says that the name derives from Opta, a brigand who renounced his mayhem, accepted the monastic name of Makary and formed a forest hermitage in the late 14th century. ("Pustyn" is related to the word for "wilderness" and was often used for small monastic communities in forests.)

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, Interior, view east toward icon screen. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Church of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, Interior, view east toward icon screen. August 23, 2014

In the 15th century, the retreat accepted both men and women who lived in separate areas but were led by a common spiritual father. This practice was banned by the Church Council of 1503, and the Optina community was reconstituted only for men as the Optina Pustyn Monastery of the Presentation. Tenuously surviving in the 16th and 17th centuries, the monastery was destitute by the early 18th century and briefly closed in the mid 1720s.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Monastery bell tower flanked by south & north cloisters. Sunday procession of monks to Refectory (on right). August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Monastery bell tower flanked by south & north cloisters. Sunday procession of monks to Refectory (on right). August 23, 2014

For centuries, Optina Pustyn consisted of wooden structures. In 1750, work began on a new main church dedicated to the Presentation of the Virgin, yet the monastery remained on the brink of destitution, exacerbated in 1764 by Catherine the Great's decree that led to the confiscation of monastery property.

By the end of the 18th century, however, the monastery and its beautiful location gained the attention of a leading church official, Platon, the Metropolitan of Moscow and Kaluga. His patronage led to a revival, including the construction in 1802-06 of a large bell tower and flanking cloisters. Throughout the 19th century other churches, chapels, and monastery structures were built, including a large refectory with imposing murals and ceiling paintings that have survived.

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat (skete). Bell tower over Holy Gate, south view. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat (skete). Bell tower over Holy Gate, south view. August 23, 2014

Of special significance was the monastery's hermitage, or skete (retreat), devoted to a strict form of spiritual observance. Dedicated to St. John the Baptist, the skete at Optina Pustyn was established in 1821 within its own compound to the east of the main monastery walls. The St. John the Baptist Skete is a hermitage closed to the public, but I was permitted to take photos there in the summer of 2014.

The skete’s focal point remains the Church of the Nativity of St. John the Baptist, built in 1822. Clad in red plank siding, the attractive wooden structure is accented with white neoclassical porticoes. Other buildings include a bell tower over the Holy Gate, small residences and a library that served as a museum during the late Soviet period.

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat. House of starets Ambrose. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat. House of starets Ambrose. August 23, 2014

During the 19th century the hermitage became widely known for its sages who achieved the designation starets, or "elder". Although the concept of starchestvo was brought to the monastery in the 1820s by the church hierarchy, the starets designation came primarily through popular respect for certain monks who led an ascetic existence at the hermitage and in whom charisma merged with deep spiritual wisdom. The church venerates all 14 monks who achieved the status of starets at Optina Pustyn.

Holy monk unhappy with writer’s pride

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat. House of starets Macarius. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, John the Baptist Retreat. House of starets Macarius. August 23, 2014

The monastery attracted all levels of society, from common folk to Russia's intellectual and artistic elite. Nikolai Gogol, Ivan Turgenev, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, the brothers Ivan and Konstantin Aksakov, Konstantin Leontiev - these are but a few of the artists and thinkers who visited Optina Pustyn. The monastery, however, is best known for its encounters with Fyodor Dostoevsky and Leo Tolstoy -- encounters that in each case involved a personal crisis.

After visits in 1877 and 1881, Tolstoy returned in 1890 to meet with starets Ambrose, a year before the latter's death. The meeting was evidently tense and difficult for the elderly monk, wearied by what he saw as Tolstoy's pride. These episodes concluded without spiritual resolution.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Monastic hermit giving blessing. Background: Holy Gate over main entrance. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation. Monastic hermit giving blessing. Background: Holy Gate over main entrance. August 23, 2014

By this point Tolstoy had publicly broken with the Orthodox Church and had attacked the basic tenets of Christian dogma and its rituals. Nonetheless, he returned to Optina Pustyn in 1896 at the urging of his sister Maria (1830-1912), who in 1891 had entered the nearby Shamordino Convent. During that visit the great writer met with starets Joseph, whose calm generosity of spirit gave him a temporary measure of peace.

Tolstoy's turbulent spiritual quest, however, would not subside. Accompanied by his physician, Dushan Makovitsky, Tolstoy arrived at Optina Pustyn toward the end of the day, October 28, 1910. During the difficult trip he asked frequently about the elders at Optina Pustyn. Despite his refusal to reconcile with the church, his anguish evidently led him to seek the wisdom and solace that they might provide.

Yasnaya Polyana. Color portrait of Leo Tolstoy taken after his return from horseback riding. First published in August issue of Notes of the Imperial Russian Technical Society. May 23, 1908.

Yasnaya Polyana. Color portrait of Leo Tolstoy taken after his return from horseback riding. First published in August issue of Notes of the Imperial Russian Technical Society. May 23, 1908.

After spending the night at the monastery, Tolstoy again approached the hermitage, or skete, on the morning of October 29. Each time he turned back, however, beset by doubt and the fear that he would not be received. Many have speculated on his motives for this unexpected visit, but there is little firm evidence about his possible intentions to reconcile with the Orthodox Church.

At this critical moment on October 29, Tolstoy and Makovitsky made their way to the Shamardino Convent, 12 km north of Optina Pustyn. There, Tolstoy visited his sister Maria, who had accepted monastic vows in 1891.

Tolstoy’s death saddens the monastic community

Shamordino. The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Cathedral of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, northwest view. August 23, 2014

Shamordino. The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Cathedral of the Kazan Icon of the Virgin, northwest view. August 23, 2014

Founded in 1884 as a women’s spiritual community (obshchina) affiliated with Optina Pustyn, in 1901 Shamordino was formally designated the Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent (pustyn). With extensive patronage from the tea merchant Sergey Perlov, the convent at Shamordino developed rapidly and by 1910 had become an important spiritual center. Tolstoy even mused about staying nearby for a time.

However, the arrival of his daughter Alexandra (Sasha) on October 30 again roused him to flight. Sasha brought news that Sonya had learned of his whereabouts, and that evening Tolstoy wrote a letter asking her not to follow him. Together with Makovitsky, they all made their way on October 31 to Astapovo Station, where Tolstoy died a week later.

Shamordino, The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Church of St. Ambrose of Optino, west view. On site of the abode where starets Ambrose of Optina Pustyn stayed during his pastorly visits to Shamordino. August 23, 2014

Shamordino, The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Church of St. Ambrose of Optino, west view. On site of the abode where starets Ambrose of Optina Pustyn stayed during his pastorly visits to Shamordino. August 23, 2014

In a final tragic turn, Tolstoy's hesitation and retreat from the hermitage quickly became known among the monks at Optina Pustyn, where the news was received with dismay. Starets Varsonofy journeyed to Astapovo but was not allowed in the presence of Tolstoy despite repeated requests. Tolstoy's closest associates had no interest in such a meeting.

Shamordino, The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Dacha of the tea merchant Sergey Perlov, benefactor of the convent. August 23, 2014

Shamordino, The Kazan Icon-St. Ambrose Convent. Dacha of the tea merchant Sergey Perlov, benefactor of the convent. August 23, 2014

In January 1918, a few months after the Bolshevik revolution, Optina Pustyn was closed. Dispersal, executions, and exile ensued. During the Soviet period most of the church artwork was lost or destroyed. The convent at Shamordino was closed in 1923, and only reconsecrated in 1990.

The Presentation Optina Pustyn Monastery was returned to the Orthodox Church in 1987 and services resumed in 1988. In 1990, the St. John the Baptist Skete was also returned to the monastery. Thus began a process of restoration whose results are impressively visible today.

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation, northeast view. East wall with Library Tower on right. August 23, 2014

Optina Pustyn, Monastery of the Presentation, northeast view. East wall with Library Tower on right. August 23, 2014

A century apart: An American professor and an Imperial era photographer

In the early 20th century, the Russian photographer Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky developed a complex process for color photography. Between 1903 and 1916, he traveled through the Russian Empire and took over 2,000 photographs with the process, which involved three exposures on a glass plate. In August 1918, he fled Soviet Russia and ultimately resettled in France where he was reunited with a large part of his collection of glass negatives, as well as 13 albums of contact prints. After his death in Paris in 1944, his heirs sold the collection to the U.S. Library of Congress. In the early 21st century the Library digitized the Prokudin-Gorsky Collection and made it freely available to the public. A few Russian websites now have versions of the collection. In 1986, architectural historian and photographer William Brumfield organized the first exhibit of Prokudin-Gorsky photographs at the Library of Congress. Since he began this project in 1970, Professor Brumfield has photographed most of the sites visited by Prokudin-Gorsky. This series of articles juxtaposes Prokudin-Gorsky’s views of architectural monuments with photographs taken by Professor Brumfield decades later.