5 foreign writers who are loved in Russia as their own

We’ve already covered which contemporary foreign authors are most popular in Russia. Among them are J. K. Rowling, Stephen King, Elizabeth Gilbert, Yuval Noah Harari, as well as many others. But what about good old classic writers?

Russians know the world’s literature very well (mostly Western, but not only). There is an obligatory school reading curriculum, which includes the likes of Charles Dickens, Oscar Wilde, Mark Twain, Edgar Alan Poe, Jules Verne, Gerbert Wales, O’Henry and many many other writers. Soviet geologists’ love for Jack London even brought a lake discovered in Siberia to be named in honor of him.

Below are the authors that Russians have the longest and strongest affairs with.

1. William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare

Shakespeare is perceived by many Russians as a very close and beloved author. In the iconic Soviet comedy ‘Beware of the Car’, the amateur theater director character says a phrase that became iconic: “Shouldn’t we, my friends, take a challenge to stage William, our, Shakespeare?” OUR William Shakespeare!

A big love for the bard started in the early 19th century in Russia with the Anglomania and many translations of Shakespeare’s works directly from English. Shakespeare literally turned the minds of Russian writers upside down.

Ivan Turgenev, who translated lots of Shakespeare, wrote that “Shakespeare’s shadow weighs on the shoulders of all dramatic writers; they cannot refrain from imitating him”. And Alexander Pushkin admitted that his historical drama ‘Boris Godunov’ was inspired by Shakespeare.

Shakespeare’s plots and characters are constantly being rethought by Russian writers. One of the most famous was Nikolai Leskov’s ‘Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk’, where he transferred the tragic plot into a Russian province.

William Shakespeare. Tragedies

William Shakespeare. Tragedies

In the early 20th century there was another boom of translating Shakespeare. One of the most classic translations was made by Samuil Marshak and Boris Pasternak. The latter felt a big influence of the Bard, and one of Doctor Zhivago's poems is called ‘Hamlet’.

In 2016, within the ‘UK-Russia Year of Language and Literature’, an entire Moscow Metro subway train was decorated with Shakespeare’s images and quotes. In 2022, one of Moscow’s most fashionable theaters staged a premier performance called ‘Hamlet in Moscow’.

Read more: Why Shakespeare is an honorary Russian

2. Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas

Alexandre Dumas was so popular in the Soviet Union that every Soviet boy read it to bits imagining to be D’Artanyan (or any of three other musketeers!). Sometimes, younger readers even didn’t know that Dumas was French. He was Alexander, just like Pushkin!

Actually, the most well known myth and conspiracy theory was that Pushkin didn’t die after being shot at a duel, moved to France and actually started writing under the name of Alexandre Dumas. There are even some common facts in their biographies that made people believe that Dumas and Pushkin were the same person. Could you imagine that?

Read more about this theory here.

Some weak translations into Russian were made of Dumas’ works in the 19th century, right after his novels were published in France. But, it seems that, back then, it was Dumas who was more interested in Russia and Russian literature than vice versa. In his novel titled ‘The Fencing Master’, a character goes to Russia as a teacher. Dumas himself also traveled to Russia and translated works of Alexander Pushkin and Mikhail Lermontov into French.

Alexandre Dumas. The Three Musketeers

Alexandre Dumas. The Three Musketeers

In the 20th century, the Russian audience opened up to Dumas, thanks to three women: Vera Waldman, Ksenia Ksanina, and Deborah Livshitz. Their co-translation of ‘The Three Musketeers’ written in 1949 was reprinted and reissued 53 times with millions of copies printed. And, of course, a later Soviet movie adaptation with Mikhail Boyarsky as D’Artanyan became iconic!

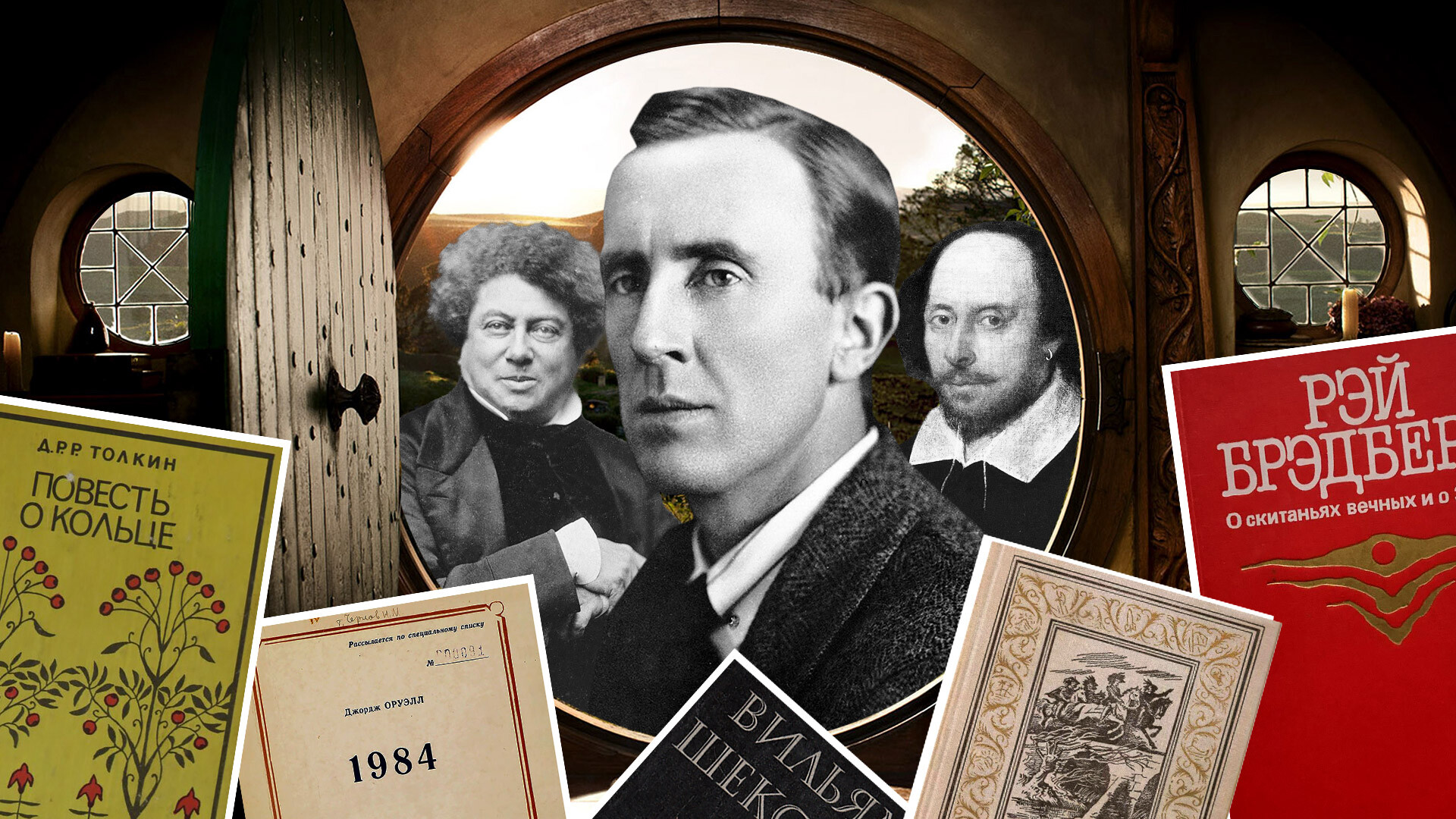

3. J. R. R. Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Tolkien gained his first admirers in the USSR back in the 1960s. At first, his books were distributed in English by volunteers, who made self-published ‘samizdat’ copies of the books that rare visitors to the West brought back. At once, several amateur translations were made, but Soviet censorship was suspicious about the “Western” author and, for a long time, Tolkien’s books weren’t officially available in the USSR. During the Cold War, Mordor could be even perceived as a metaphor for the USSR.

The first translation of ‘The Hobbit’ saw the light in 1976. The story was perceived as a fairy tale, so was approved by the censors and, moreover, soon staged in youth theaters. However, ‘The Lord of the Rings’ had a less lucky fate. The first time Soviet censorship allowed it to be published was in 1982, when the first volume was issued in a translation by Andrei Kistyakovsky and Vladimir Muravyov. Poor fans had to wait another eight years for the publication of the second and third volumes (due to the disgrace and then the death of one of the translators).

J. R. R. Tolkien. Story of a Ring

J. R. R. Tolkien. Story of a Ring

There were two Tolkien screen adaptations on Soviet TV much earlier than Peter Jackson’s movies: ‘The Fabulous Journey of Mr. Bilbo Baggins’ (1985) based on ‘The Hobbit’ and ‘The Keepers’ based on ‘The Lord of the Rings’.

Already in the 1980s, a whole subculture of Tolkienists had formed in the USSR after the official translations. Fans of Tolkien and his Middle-earth even held large-scale role-playing games.

The love and interest has not subsided to this day. Tolkien is included in the facultative reading curriculum in schools. Today, there are dozens of translations of ‘The Lord of the Rings’, the linguistic and artistic features of which are still debated among experts and fans, who compare them with each other and with the original.

4. George Orwell

George Orwell

George Orwell

Since 2010 (!) and until now, George Orwell’s dystopian novel ‘1984’ has been leading book sales in Russia, with about two million copies sold during that period. And while the interest in this book is only growing, the Russians’ love for Orwell started long ago.

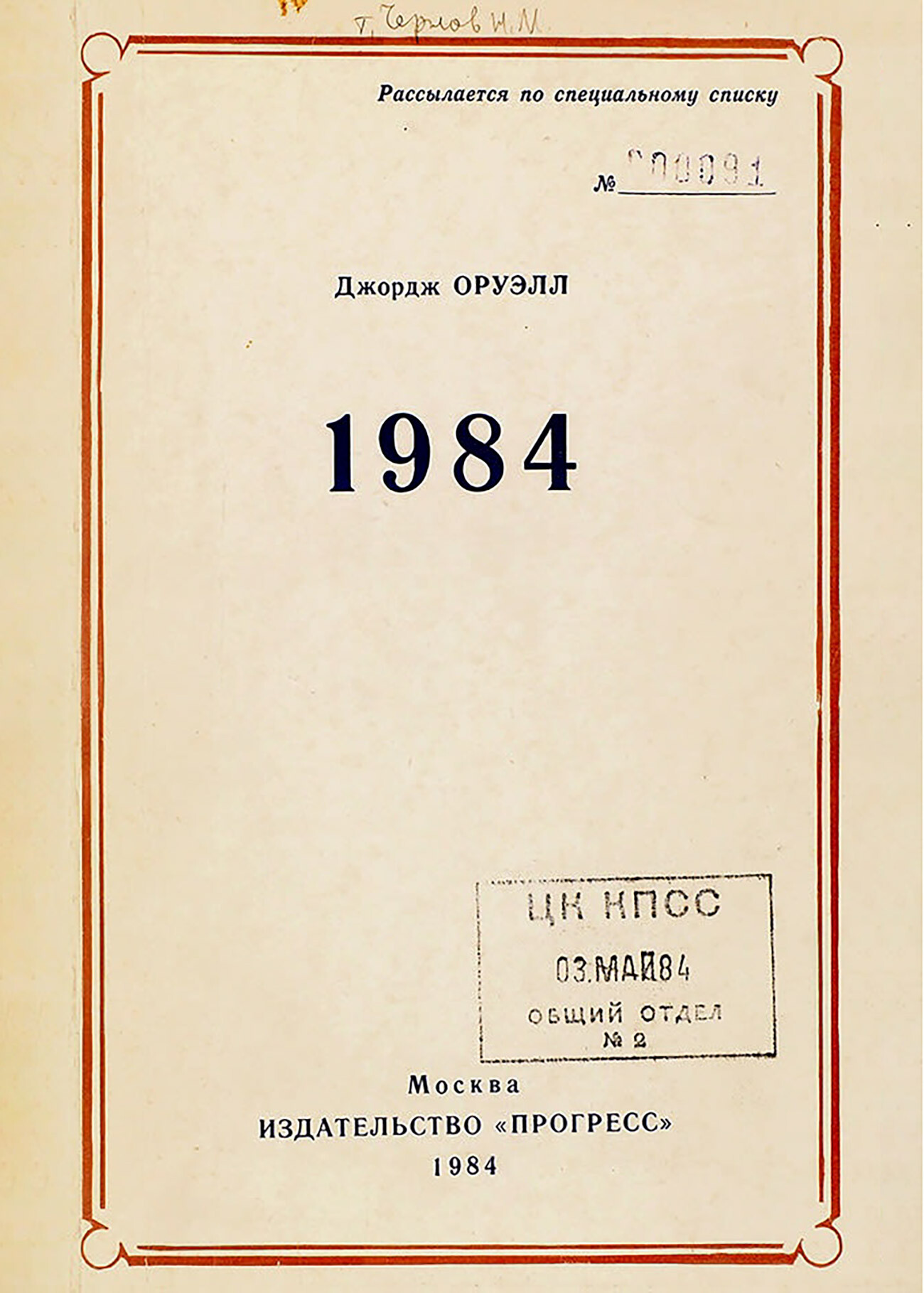

His books were banned in the USSR for many years and, as everything banned, it caused a huge interest. And, in the 1960s, ‘1984’ and ‘Animal Farm’ (that both had obvious allusions to the Soviet Union) were self-printed and spread via ‘samizdat’.

‘1984’ was only published in the USSR in 1988, ironically after the future it was foretelling. Even then, the novel gained great popularity among Soviet readers.

George Orwell. 1984. A copy that was distributed according to a special list approved by the Communist Party.

George Orwell. 1984. A copy that was distributed according to a special list approved by the Communist Party.

By the way, before writing ‘1984’, Orwell read the dystopian novel ‘We’ (1920) by Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin and was deeply impressed by it. Orwell acknowledged his own literary debt to Zamyatin and numerous scholars have since highlighted the similarities between the two.

The dystopian genre was favored by Soviet readers, who compared it to the reality they lived in.

Read more about what connects Orwell to Russia here.

5. Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury

Ray Bradbury

“In the USSR, they published ‘The Martian Chronicles’, but they didn’t give me a ruble! And I really like rubles!” Ninety-year-old Bradbury joked in 2010 in an interview with a Russian newspaper.

Indeed, Bradbury’s stories came out in print runs of millions of copies. He was a favorite young adult author and one of the most popular sci-fi authors, a genre which faced a boom in the USSR (when reading about reality was politicized).

Written in 1953, ‘Fahrenheit 451’ was published in the USSR in 1956, while, in the U.S., it was banned for a long time. Soviet authorities probably decided to support the author who spoke out against McCarthyism, censorship and excesses of political correctness.

In the 1960s, everyone in the USSR was passionate about space, so millions of Soviet people read Bradbury’s ‘The Martian Chronicles’ issued in Russian in 1965. And the novel was adapted to the big screen several times in the 1980s.

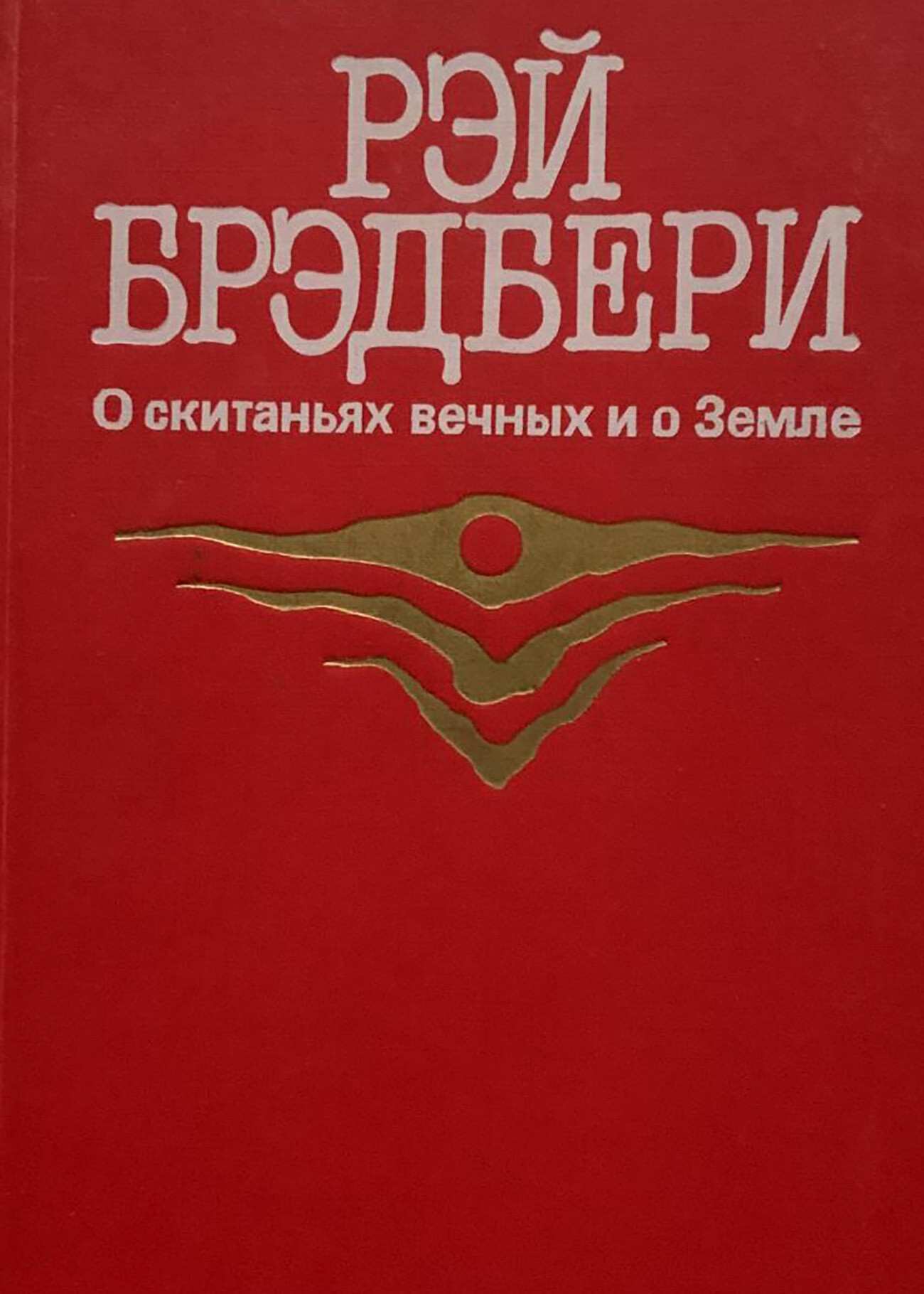

Ray Bradbury. About Eternal Wandering and About the Earth

Ray Bradbury. About Eternal Wandering and About the Earth

A compilation book titled ‘About Eternal Wandering and About the Earth’ was then released and included both ‘Fahrenheit 451’, ‘The Martian Chronicles’ and other stories. So, on the shelves of many Soviet homes one could find (and still can in some places!) the iconic red, brown or green colored cover with its recognizable laconic design!

Most Soviet readers didn’t care about Bradbury’s political and critical messages in the books. They simply enjoyed dystopian science fiction and his imaginary worlds.