What icons were called ‘hellish’ or ‘adopisnye’ and where did they come from?

Behind the Cracks - into the Fire

The apocryphal life of St. Basil describes an episode when the saint suddenly broke the miracle-working icon of the Mother of God on the Varvarka Gate with a stone. Outraged people beat him. But, he did not say anything in his defense, only ordered to scrape the paint off the canvas. When the parishioners did this, they saw that the devil was drawn under the holy image. And what was supposed to be a miracle was, in fact, an obsession, which seduced the faithful. The icon painter was executed, and they apologized to the holy fool.

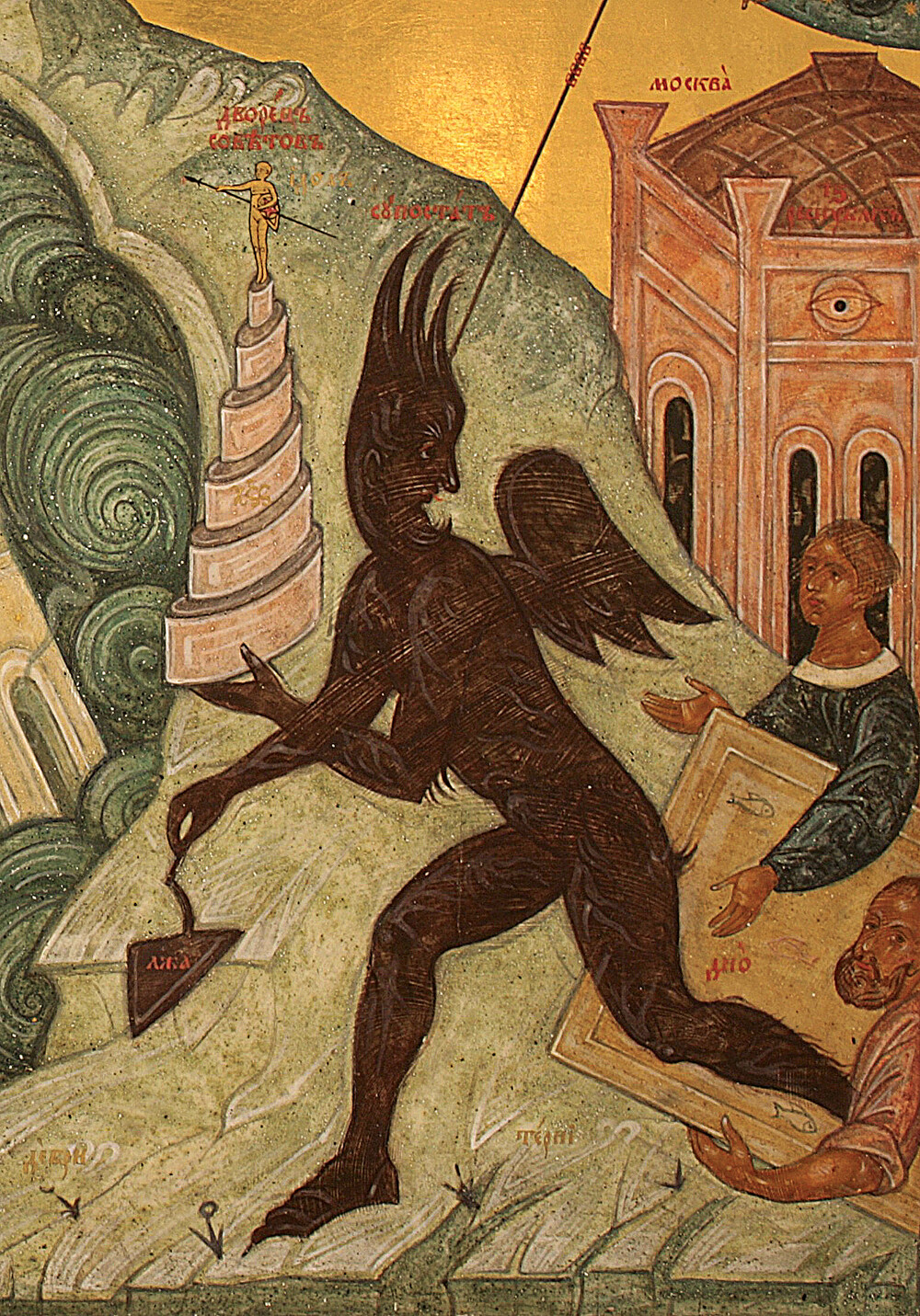

It is believed that this is one of the first mentions of the so-called ‘adopisnye’ or hellish icons - images of devils were hidden under the faces of saints, behind the frames, and sometimes even horns were added. It was believed that a person praying in front of such a double-image icon unknowingly was turning to the forces of hell.

In the 19th century, there was a wave of reports about hellish icons swept across Russia, they were allegedly found in one region, then in another. For example, the ‘Moskovskie Vedomosti’ newspaper reported: "In the village of Stetsovka, Kherson Province, the local clergy demanded that all the existing foil icons be certified as ‘suitable’ by lifting the cardboard. Local residents claim they had found about five devilish images."

It got to the point that any crack or unevenness in the paint layer of the icon was perceived as the machinations of evil spirits - after all, images of the devil could be hiding there. Therefore, peasants resolutely sent such paintings into the fire.

Just Business

Writer Nikolai Leskov, in his essay titled ‘About adopisnyh icons’, talked about how such images appear and how to distinguish them from real ones.

They were made from cheap materials (this is the reason why the paint layer cracked so quickly) and more often in the so-called ‘Fryazhsky’ style - it emerged in the 17th century under the influence of Western European painting and was distinguished by the realism of the images. Who could do this? One of the popular versions connects these images with the Old Believers (‘Starovery’) - they didn’t accept the Fryazhsky style. However, there is no evidence for this. Neither is there any evidence that the hellish icons appeared as a result of the confrontation between heretics and the official church.

But, Leskov very vividly described the business scheme by which such icons could exist. One merchant sold "fakes of antiquity" with devils hidden under the paint, which were drawn specially for him. And a second merchant, following him, would "expose" his fellow. For the sake of appearances, upset that people had already bought the images, he asked to show them the icons, confidently scraping the paint on the place where the evil spirits were depicted. And he immediately reported that these icons "are not Christian, but hellish". "The peasants are greatly horrified on this occasion and give the scoundrel all their "adopisnye" icons on which the devils are open, just so that he can take them away and they buy or exchange others from him, on which they do not expect such a surprise for themselves," wrote Leskov.

Wicked Joke

Perhaps the appearance of such icons was someone's cruel joke. For example, writer Maxim Gorky confessed that, during his short work in an icon-painting workshop, he continually used to encourage painters to draw horns. For which he was nicknamed ‘little devil’. When he was fired, one of the icon painters gave him an icon with the image of the devil, painted especially for him. He confessed to writer Ilya Surguchev: "I could never part with it. It was even in the Peter and Paul Fortress with me. They took all my things, but it was left behind."

There is another, more prosaic explanation. Perhaps the peasants mistook quite ordinary icons, such as those of the Last Judgment or with the plot of the temptation of a saint by evil forces, as hellish-painted ones. Or they might have considered the image of St. Christopher, who was painted with the head of a dog, as "bad".