How the French perfumed all of Tsarist Russia

Alphonse Rallet

Alphonse Rallet

In 1842, a 23-year-old Frenchman named Alphonse Rallet came to Moscow, where, a year later, he founded his own perfume factory and began to produce all kinds of “fragrant goods” – perfume, soap, cologne, powder, lipstick and creams. Already in 1855, he received the title of ‘Supplier to the Court of His Imperial Majesty’, which testified to the highest quality of products and gave the right to put the Russian coat of arms on the packaging. The company would later receive this title three more times.

In the 1860s, Rallet and his new partner Emile Baudrand already had two factories – in Moscow and Kharkov, both employing up to 200 workers. At the end of the decade, Rallet himself returned to France, but the brand ‘Alphonse Rallet and Co.’ (A. Rallet et S-te), which had won the trust of customers, remained: the company did not change its name until 1918.

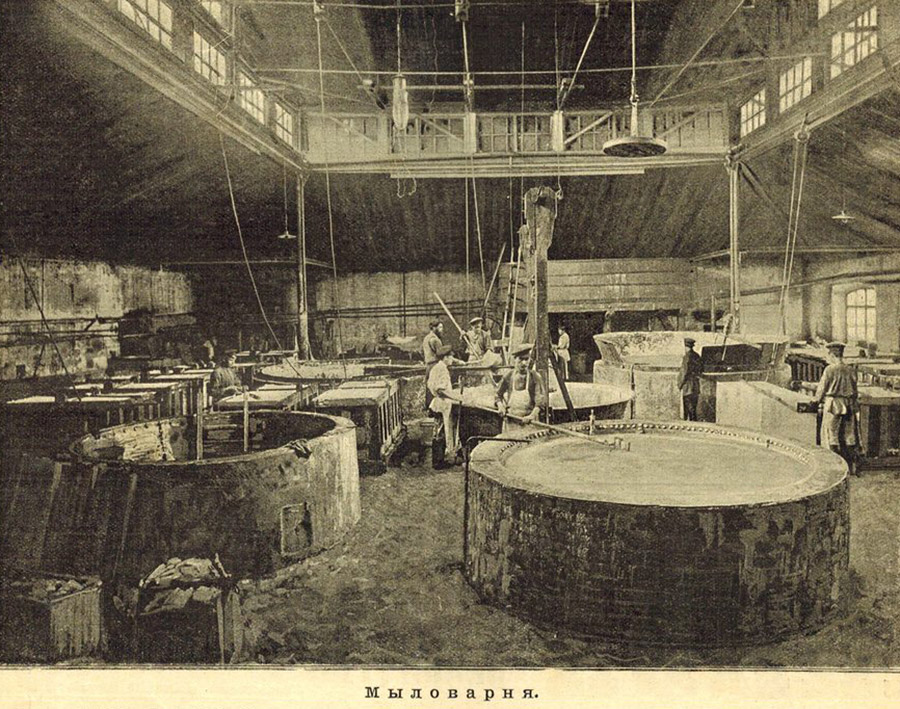

The factory was famous for its diverse products. Among the most important ones were: more than 2.4 million bars of soap per year, 1.5 million jars of hair pomade, 238,000 bottles of perfume, 1.6 million bottles of cologne and 23,000 boxes of rice powder. It also produced scented oils, fixatives, tooth powder, face cream and various air-freshening items for living rooms, such as “water for smoking in rooms”, smoking paper and scented smoking candles. In the 1880s, the company's products accounted for 37 percent of all cosmetic production in Russia.

A new era

In 1898, a new stage began: the factory was bought by Chiris, a French perfume company known since the 18th century. The family company from the city of Grasse was a leading producer of raw plant materials for the perfume industry throughout Europe.

The new owners built a large factory building in 1899 and equipped it with the most modern equipment.

The heyday of the company's perfumery business came at the beginning of the 20th century, when one of the directors, famous Adolphe Lemercier, became the chief perfumer. From 1902, under his mentorship, the talent of Ernest Beaux, son of the managing director, matured there. Today, Beaux is one of the most famous perfumers of the past – the creator of the legendary Chanel No. 5 fragrance.

And Beaux’s first success came in Moscow, when he created the floral ‘Tsar's Heather’ fragrance. In 1912, another of his products became a hit, released to mark the 100-year anniversary of the Patriotic War of 1812 – the ‘Le Bouquet de Napoleon’.

The perfumes were made using French technology and the essences were obtained from Grasse – the famous “province of perfumers”. Other aromatic components from all over the world were also obtained through French suppliers, such as geranium essence from Reunion Island in the Indian Ocean and Algeria, rose oil from Bulgaria and ylang-ylang from the Philippines.

From advertising to a new name

The owners sought to attract customers with both the quality of the products and elegant packaging. They used cardboard boxes with richly colored drawings, tin boxes for powder and soap and boxes for travel kits that had several compartments with drawers. As early as the 1860s, the production of glass bottles of various shapes and sculptural stoppers was opened in Moscow. For example, the ‘Le Bouquet de Napoleon’ series of bottles depicted a French eagle and as, a bonus, the buyers received a colorful jubilee album titled ‘In memory of the Centenary of the Patriotic War’, with texts and drawings based on Leo Tolstoy's novel ‘War and Peace’.

The company spent huge sums on advertising, releasing postcards, notebooks, calendars and pencils bearing the logo. For the New Year of 1893, ‘Rallet’ was one of the first Russian enterprises to issue a special advertising calendar. Its description was even included later in the manual on how to create advertising: “The most elegant of Moscow advertisements is a free calendar with very elegant watercolor polytypes and blank pages for daily notes.”

The products of the Rallet factory were a huge success at the 1900 World Exhibition in Paris – the company received the highest award, the Grand Prix. By then, its products were already known to everyone in Russia. It’s no coincidence that the essay on the history of the company said: “There seems to be no corner in Russia, where their works would not have penetrated.”

After 1917, the factory was nationalized and Ernest Beaux left for France. And, in 1922, it was renamed the ‘Svoboda’ factory, which still operates according to its original profile today.

This material is published in abridged form – the original was published in the ‘Russky Mir’ magazine.