How MOSAICS for the Moscow Metro were created in besieged Leningrad

It’s hard to believe, but some of the beauty of the Moscow Metro was also created in besieged Leningrad. In the city surrounded by the Germans, where people were dying right on the streets from starvation and cold, great master craftsman Vladimir Frolov, under the light of a kerosene lamp, created his last masterpieces, all alone. Today, they decorate the plafonds of the central stations of the Moscow Metro. Many passengers and tourists look up to see an astonishingly blue sky, beautiful men and women in work suits and soaring planes over them.

Novokuznetskaya metro station.

Novokuznetskaya metro station.

A mosaicists’ dynasty

Vladimir Frolov was literally destined to become a mosaicist – that’s what his entire family did. Vladimir’s father studied a special (reverse) mosaic method from an Italian master craftsman named Antonio Salviati. In this method, the craftsman creates the mosaic front side down and then pours on cement or glue. After that, the mosaic is flipped; if needed, seams are painted over or lined with pieces of glass to make the mosaic look complete. Such a method of creating mosaics allowed them to be made fast, preserving the high artistic qualities of the panel.

Vladimir Frolov.

Vladimir Frolov.

Later, the older brother of Vladimir, Alexander, also joined the business; in 1890, the Frolovs founded the first private mosaic workshop in Russia. The workshop fulfilled many interesting commissions, the largest of which was the Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood (a magnificent building erected in St. Petersburg on the place of death of Russian Emperor Alexander II, inspired by Saint Basil’s Cathedral) – it was covered by mosaics entirely inside and out (the mosaic’s area totals 7,500 square meters). During the process of this mosaic’s creation, Vladimir’s older brother Alexander suddenly passed away and Vladimir had to take full responsibility for the work, although, at that moment, he still hadn’t graduated from the Academy of Arts.

The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood.

The Church of the Savior on Spilled Blood.

After the 1917 Revolution, Frolov’s life changed dramatically – the family workshop was closed, but Vladimir continued to make mosaics at the Academy of Arts. The master craftsman, ingeniously decorating churches, now was decorating train stations, revolutionary hero monuments, theaters, military academies and government buildings. At some point, Soviet authorities even wanted to ban mosaic art for its association with religion, but Frolov was saved by Alexey Shchusev, the Lenin’s Mausoleum architect, who demanded the interior to be decorated specifically with smalt (cobalt glass) and by Frolov’s hands. According to legend, the colored glass given to decorate the mourning hall had even, at some point previously, been bought by Nicholas II.

How the Leningrad mosaic ended up in the Moscow Metro

The Moscow Metro, the rapid construction of which began in 1931, was not only created as a means of transportation – it was given a significant ideological function. The project was considered so important that its construction didn’t stop even during World War II and the construction workers were not called up to war, even with a severe lack of soldiers.

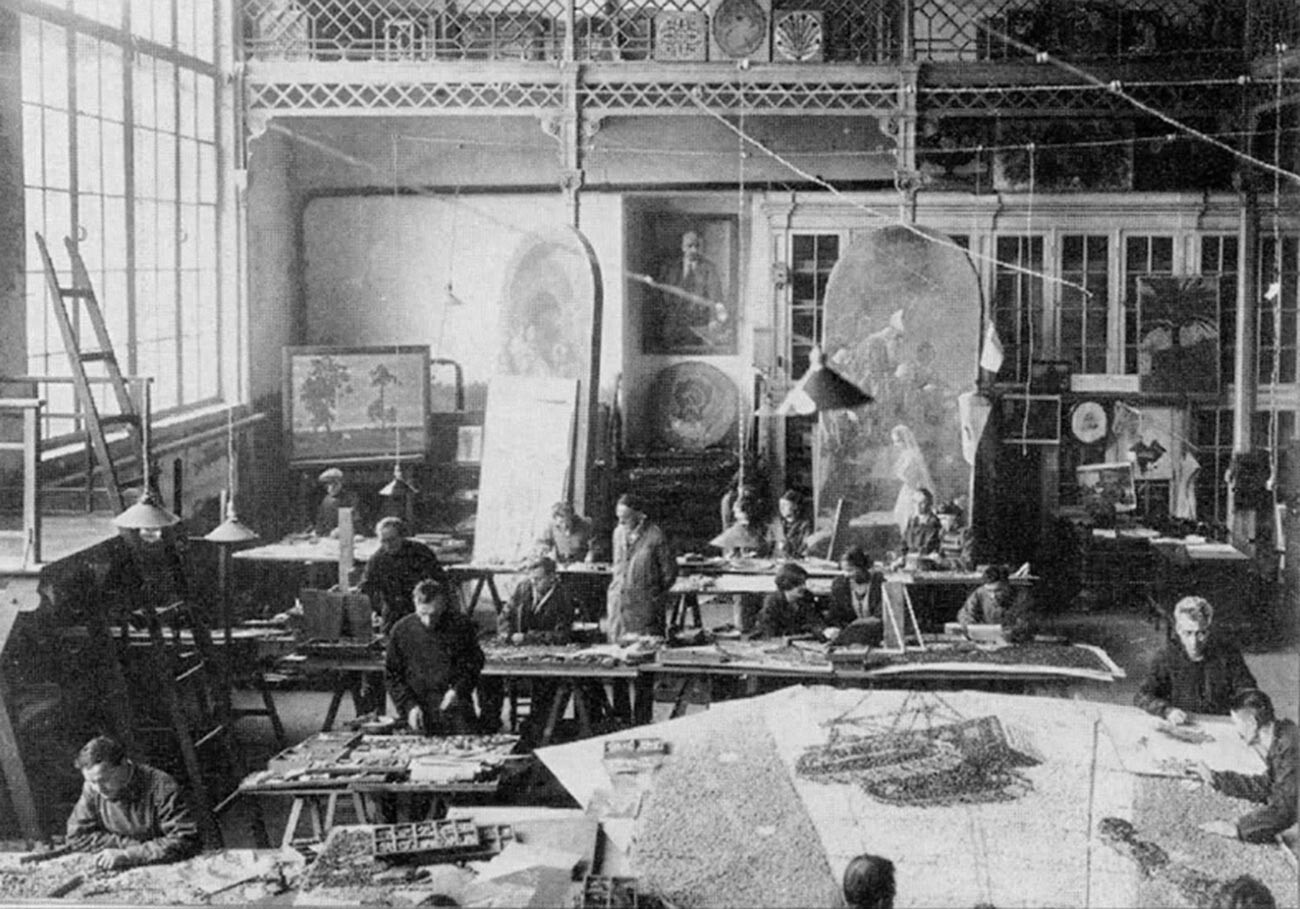

Working on mosaics for Paveletskaya metro station, 1940.

Working on mosaics for Paveletskaya metro station, 1940.

According to the plan of the Soviet government, the subway should have become the symbol of a new socialist society and the victory of the working class. A common person, descending into the metro, should have not only come in touch with the technical progress achievements, but also be amazed by its palace architecture and art masterpieces in its decorations. They didn’t skimp on marble and other expensive materials in the decoration of the metro palaces and mosaics fit such a concept well. Frolov was tasked with their creation.

After receiving the order, the master craftsman managed to create and send from Leningrad to Moscow a consignment of panels before the war, based on the drawings of a famous painter named Aleksandr Deyneka. These adorned the vestibules of two central stations of the Moscow Metro, Mayakovskaya and Novokuznetskaya.

Mayakovskaya metro station.

Mayakovskaya metro station.

The panel for the Avtozavodskaya station Frolov had to make under siege (from September 8, 1941, St. Petersburg was besieged by the Nazis). Slowly, hunger and cold crept into the city, the supply of foodstuffs had practically stopped. Many of Frolov’s colleagues managed to evacuate, but the artist himself refused, because then he would have to abandon the work of his life and the order would have been left unfinished. As such, almost alone, in the almost unheated building of the Academy of Arts (he could only get one gas canister as help), surrounded by the freezing and dying city, he continued to make beautiful mosaics.

"The Road of Life".

"The Road of Life".

Delivering a panel from besieged Leningrad to Moscow was another problem. According to legend, it was made possible thanks to engineer Taubkin, who managed to take it out of the city over the frozen Lake Ladoga (dubbed the “Road of Life”) in winter 1942. This was Frolov’s last work, as he didn’t survive the winter of 1942 and was buried in a mass grave of the professors of the Academy of Arts in Leningrad.