How did noise music appear in Russia?

In 1769, Jacob von Staehlin, a historian of fine arts in Russia, recorded: "I must also mention in passing one special music that can be discovered in Siberian foundries, to which the workers of the forges and village girls sing and dance merrily, just like others to the sounds of exquisite instruments. Two guys or blacksmith workers serve as musicians, one of them scrapes or moves a blunt knife or a piece of iron on a thin iron sheet to the beat of the dance, while the other uses a suspended thick cast piece of iron, often replaced by a large iron cauldron, to represent the bass."

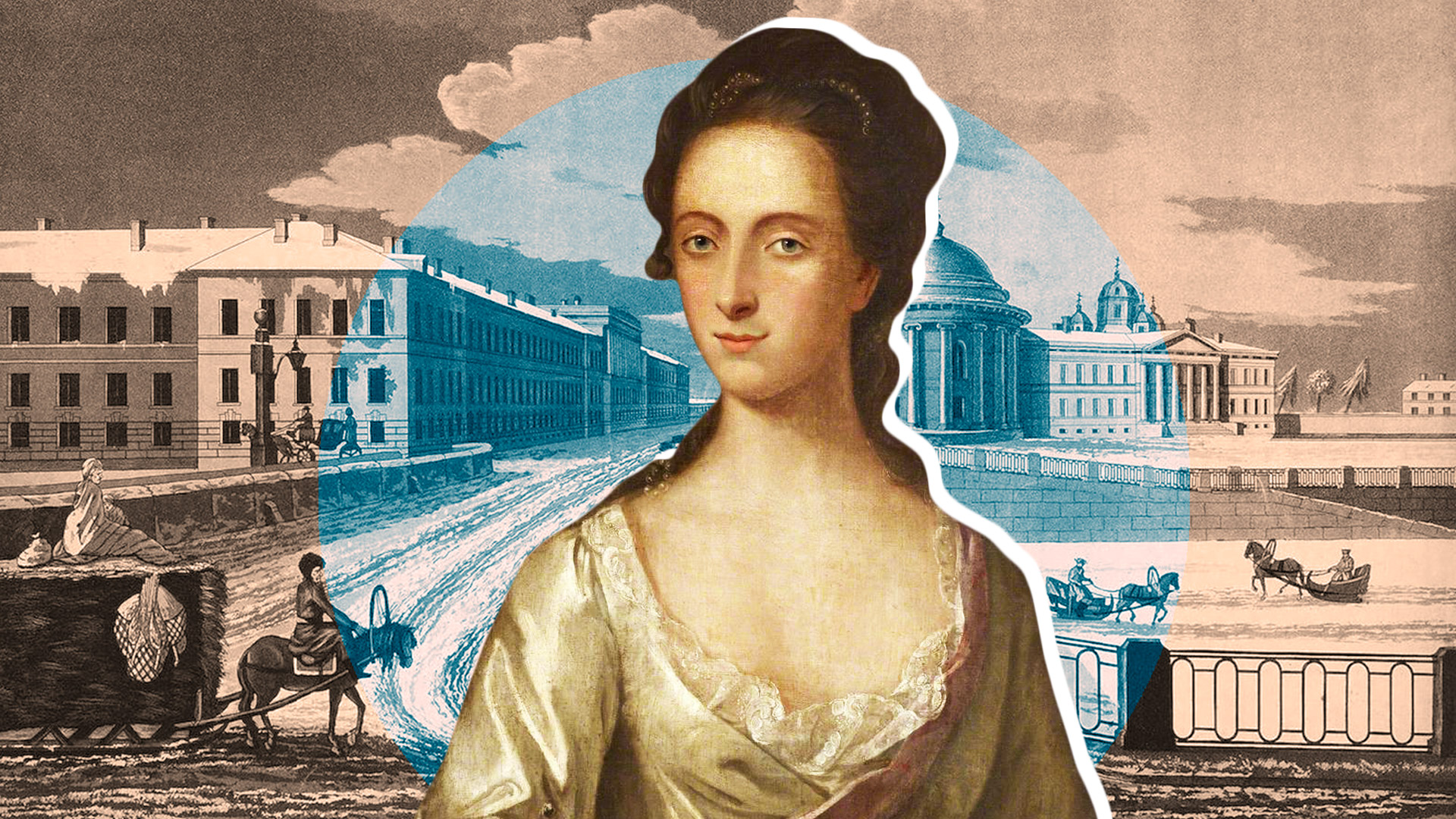

Jacob von Staehlin (1709-1785)

Jacob von Staehlin (1709-1785)

However, these performers of noise music were not musicians. Officially, the first person in Russia who intended to use various forms of noise in a musical composition was Pyotr Tchaikovsky.

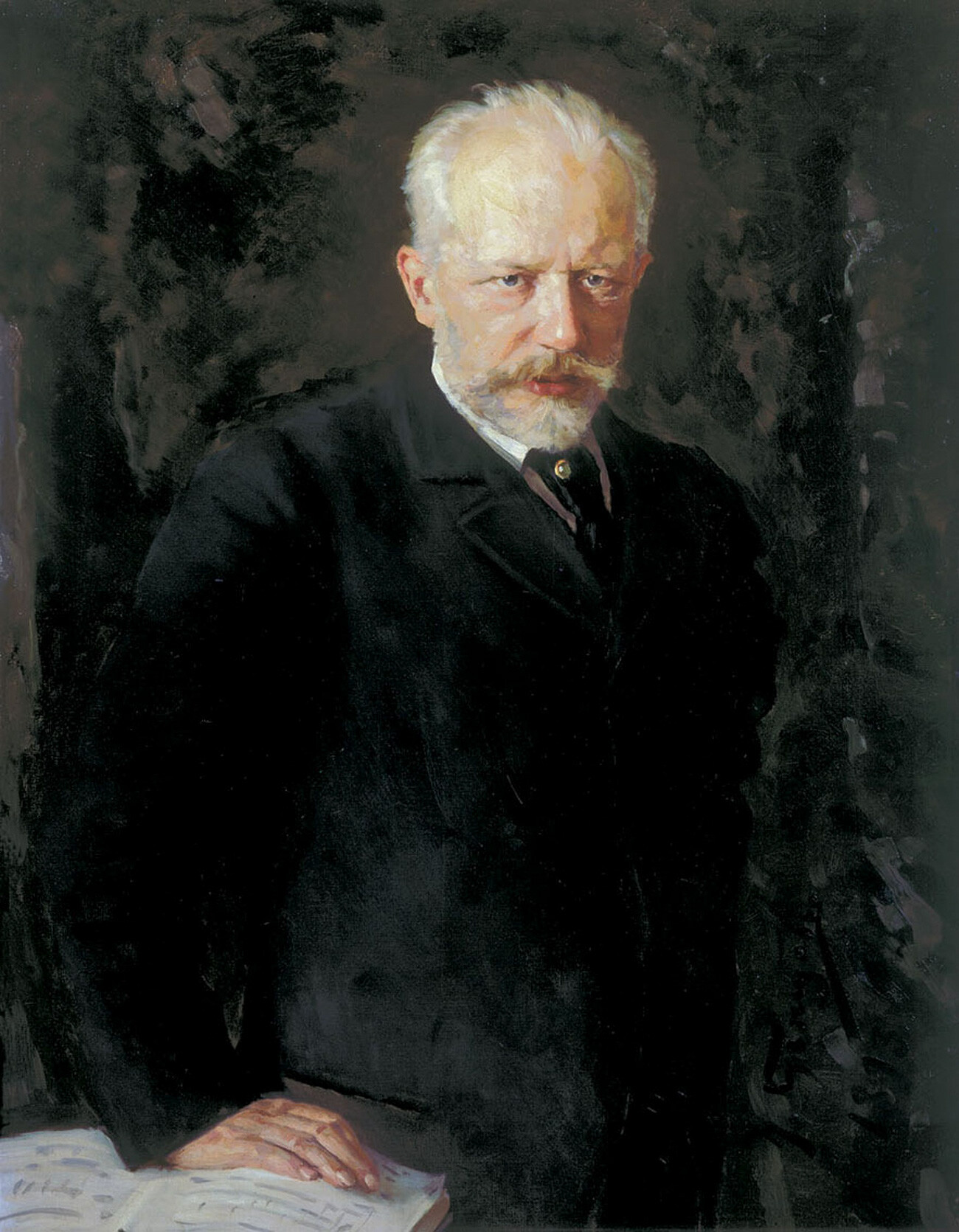

Pyotr Chaikovsky (1840-1893) by Nikolai Kuznetsov

Pyotr Chaikovsky (1840-1893) by Nikolai Kuznetsov

In his famous "1812 Overture", written for the 70th anniversary of the victory over Napoleon, the composer included the sounds of cannons and church bells. On August 8, 1882, the overture was performed for the first time on the square in front of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, which was still under construction. The cannons were lined up on the sides of the orchestra and fired to the rhythm of the music. The overture was enthusiastically received, and it was performed again on May 26, 1883, during the consecration of the cathedral.

"A solemn procession around the Christ the Saviour cathedral" by Vasiliy Surikov

"A solemn procession around the Christ the Saviour cathedral" by Vasiliy Surikov

The first Russian musical work with a full noise scene (and not individual notes, as in the case of Tchaikovsky's cannons) was created by the avant-garde composer Mikhail Matyushin. In the futuristic opera “Victory over the Sun” (1913), which Matyushin created together with the poet Alexei Kruchenykh and the artist Kazimir Malevich, there was a scene with a parade over which airplanes flew.

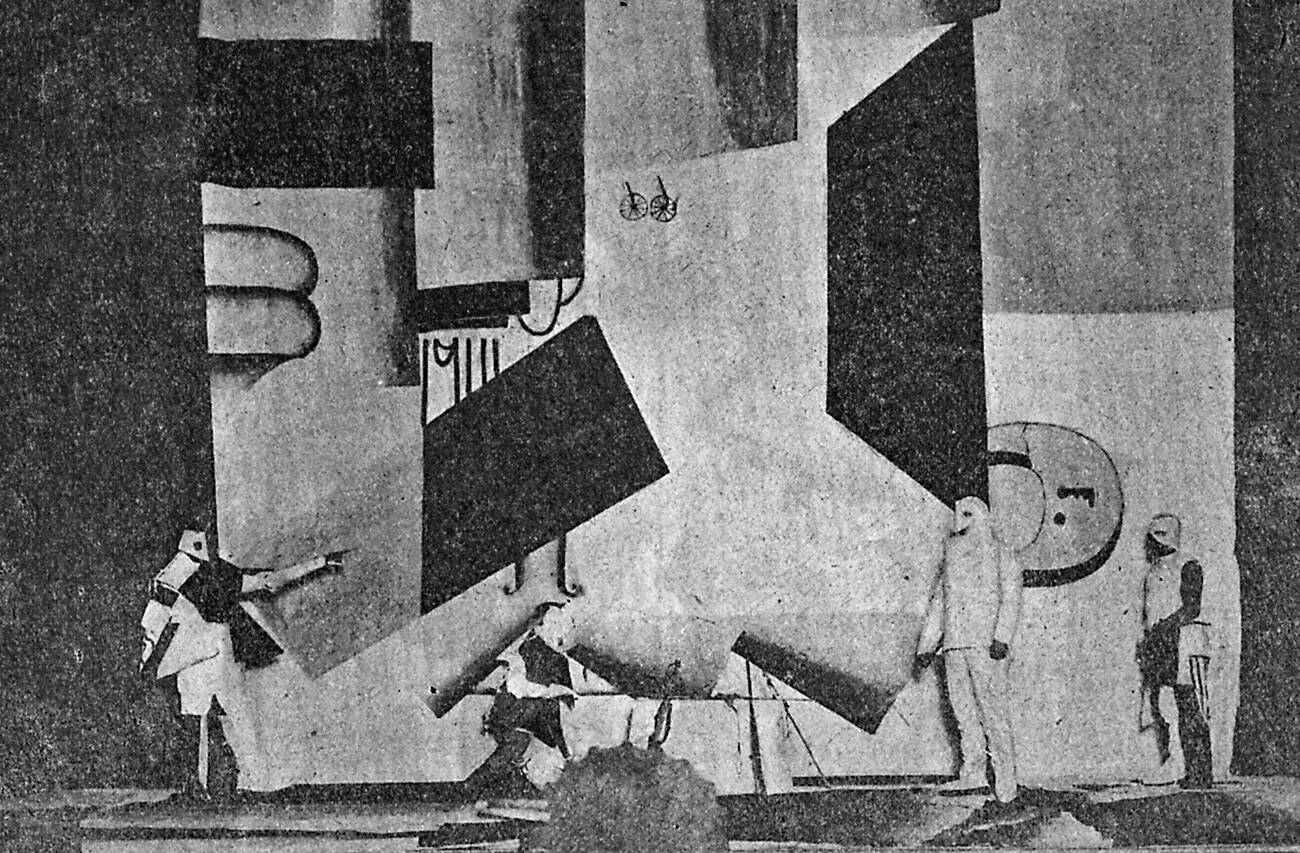

"Victory over the Sun" play, first production

"Victory over the Sun" play, first production

The propellers really should have been making noise in this scene. It is unknown, however, whether they were actually included in the first productions of the opera.

Noise and horns of the Revolution

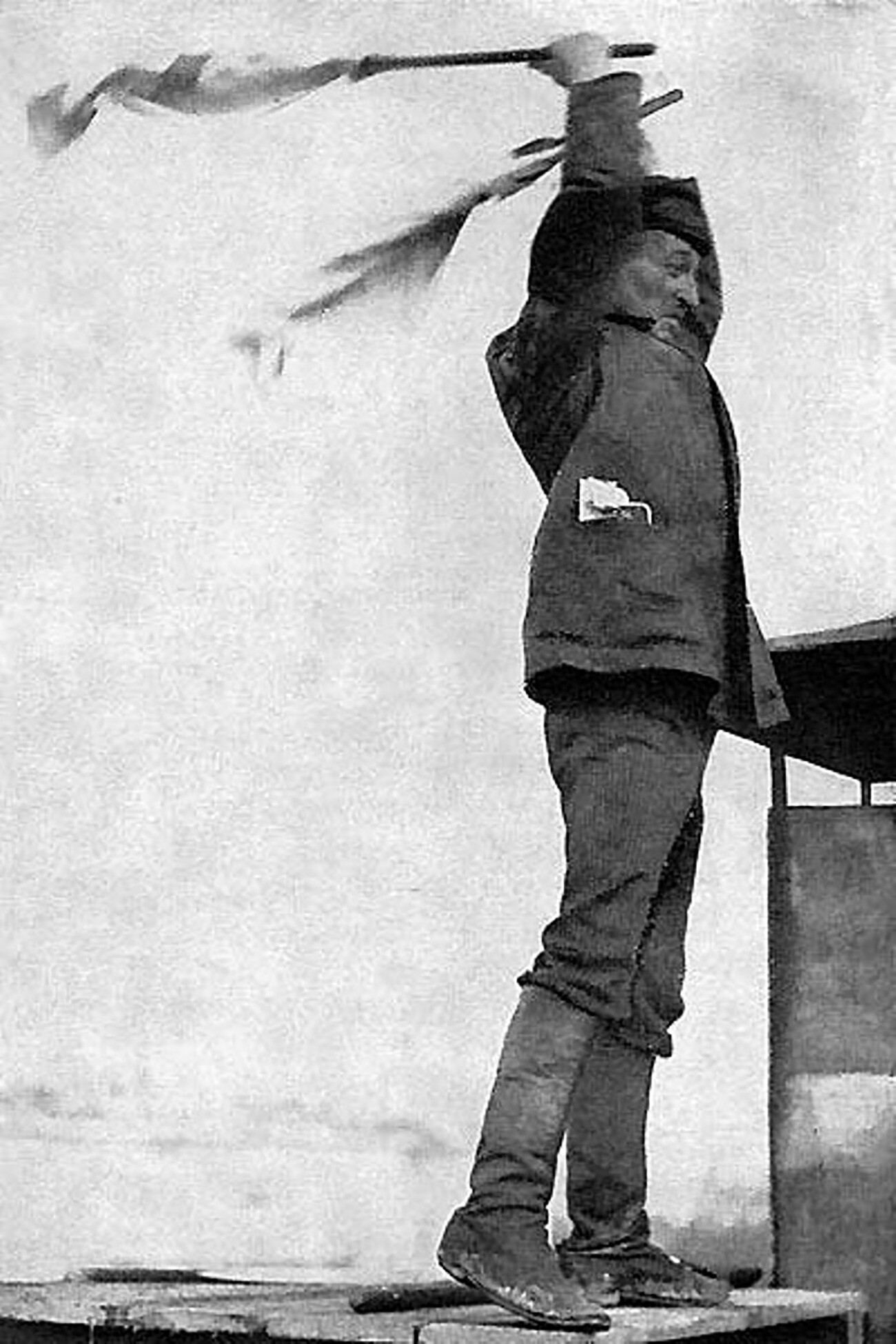

Arseniy Avraamov conducting “The Symphony of Horns”

Arseniy Avraamov conducting “The Symphony of Horns”

In Soviet Russia, ‘noise music’ experienced rapid development – in all spheres of art there was an era of the avant-garde. Revolutionary, stereotype-breaking ideas elicited much interest from the general public. In Decree No. 1 on the Democratization of the Arts (signed by avant-garde artists Vladimir Mayakovsky, Vasily Kamensky and David Burlyuk), the authors stated: "From now on, when passing down the street, a citizen will [...] listen to music – melodies, rumble, noise – by wonderful composers everywhere."

On November 7, 1923, the stage of the First Workers' Theater of the Moscow Proletkult (the production was staged at the Hermitage Garden Theater) saw the premier of a play directed by Sergei Eisenstein. “Do you Hear, Moscow?" was staged as a propaganda production about the victory of the workers over the bourgeoisie. During the intermission, the audience could see how real workers (who played workers in the play) were building a podium – this was the actual noise music part of the production.

Arseniy Avraamov, first Russian noise music composer

Arseniy Avraamov, first Russian noise music composer

Arseny Avraamov, the author of the musical excerpt, described it as follows: "the music of carpentry tools is noisy: 2 files, a handsaw and a mechanical saw, a sharpener, axes, hammers, sledgehammers, logs, nails, planes, chains, and so on… At the same time, there are no props – everything is genuine labor, coordinated rhythmically and harmoniously."

Avraamov's most famous noise work is “The Symphony of Horns”, which provides for the use of cannon and pistol shots, factory horns, steam whistling, aircraft noise and other "machine" sounds. The main instrument was the "honk line" – from 20 to 50 steam horns installed on the main steam pipe. however, it was possible to perform the composition on steam locomotive and steamship horns, "in case of a sufficient number of mobile boilers (locomotives and ships) and the possibility of their concentration in one area (railway station, railway pier)." The Symphony of Horns was actually performed in Baku in 1922 and in Moscow in 1923.

Arseniy Avraamov at the piano

Arseniy Avraamov at the piano

Avraamov emphasized that the sound of the horn is a symbol of the new life of the proletariat, because with the factory horn the worker goes to the factory in the morning; and with the horn after the end of the shift he returns home.

In the 1920s, noise music was so popular that schools and institutes even made "shumorki" – an abbreviation for ‘noise orchestras’.

By the 1930s, however, the avant-garde in music was on the wane – under the directives of the Communist Party all areas of art and culture were rapidly formalizing and replacing the experiments of the 1920s. Noise music remained relevant only for the design of individual scenes for movies and performances.

Vladimir Popov (1889-1968), sound effects pioneer in the Soviet cinema

Vladimir Popov (1889-1968), sound effects pioneer in the Soviet cinema

In 1951, the main "noise maker" of the USSR, People's Artist Vladimir Popov, received the Stalin Prize "for theatrical work in the field of sound design of performances" – during his life he created more than 200 different noise machines.

And although noise and industrial music in Russia will begin to develop again only in the 1980s, its foundations were laid in the 1910s-1920s, much earlier than such stars of specific music as Pierre Schaeffer or John Cage began their work.