From Baden-Baden to Berlin: German towns in which Russian writers lived

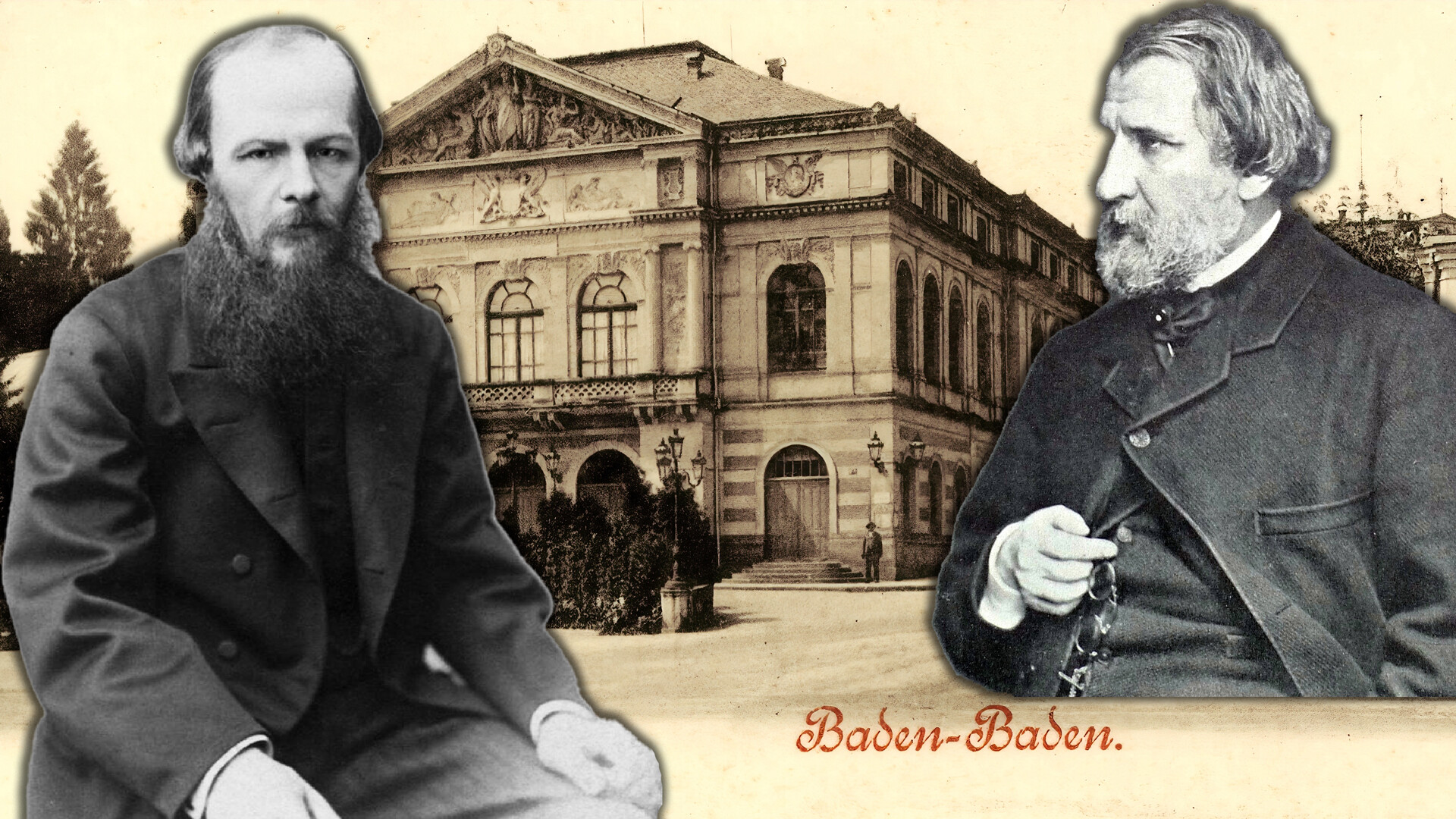

Baden-Baden

The "summer capital of Europe", as Baden-Baden was known in the 19th century, was frequented by many Russian writers, including Leo Tolstoy, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Nikolai Gogol and Anton Chekhov. Russians were popular here. "No other nation can beat them in terms of politeness, good taste, elegance and liberal views," observed the local newspaper, Badenblatt.

View of Baden

View of Baden

The town’s popularity among writers began with Vasily Zhukovsky, a poet who introduced German Romanticism to Russia, translated Goethe, Schiller and the Brothers Grimm, as well as tutored the future Emperor Alexander II. In 1827, he visited Baden-Baden on his way to Paris and in 1848 settled here with his German fiancée, Elisabeth von Reutern, to improve her health. Their wedding took place in another German city, Düsseldorf.

In Baden-Baden Zhukovsky spent the final years of his life. The following words are attributed to him: "A place marked by God, where there is absolutely no contradiction between nature and civilization, at any time of year it is a little bit of paradise on earth here".

Promenade in Baden-Baden, 1860

Promenade in Baden-Baden, 1860

Ivan Turgenev also intended to settle here. One of the most important Russian authors of the 19th century, he lived in Europe for many years. He came to Baden-Baden pursuing the woman he loved - opera singer Pauline Viardot - and lived here from 1863 to 1870, building a villa which became the town's cultural center. The action of his fifth novel, "Smoke", takes place in Baden-Baden.

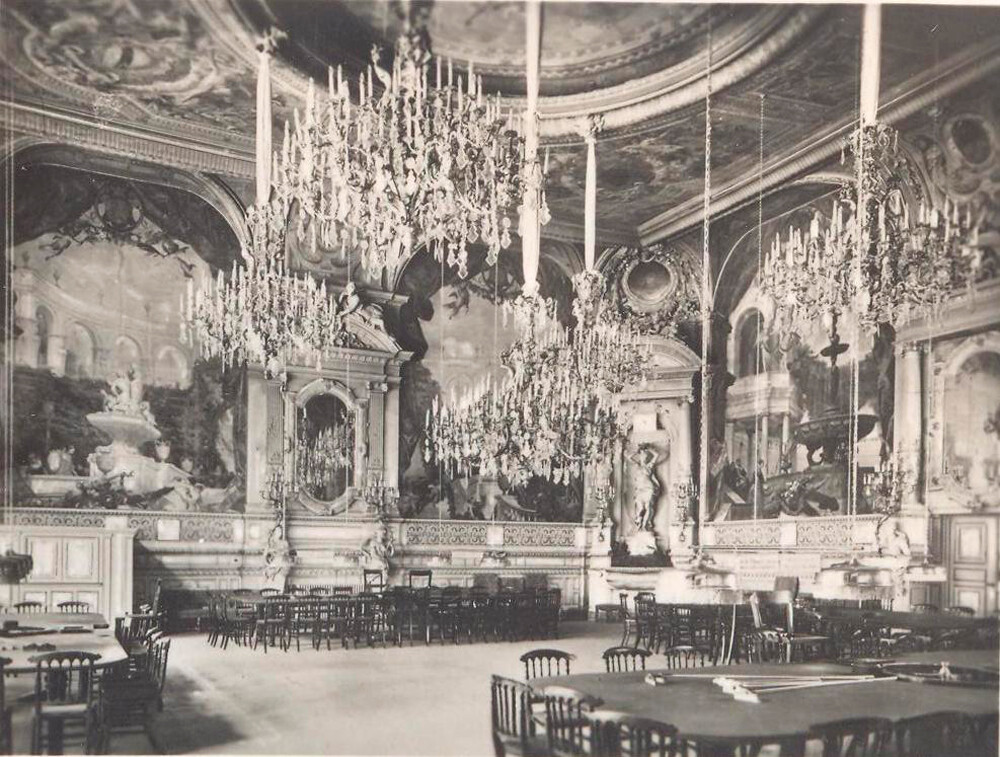

Writers were also drawn to the local casino, where many eminent men of letters frequently lost their money. Poet and diplomat Pyotr Vyazemsky was even recalled from the diplomatic service for playing at the roulette tables. Leo Tolstoy, when he visited the spa town in 1857, lost all his cash at the casino, borrowed more from acquaintances and then lost that, too. He never visited Baden-Baden again. But Fyodor Dostoevsky came here on more than one occasion. In 1863 he lost the money of his mistress together with his own, and in 1867 he gambled away not only his money but also his suit, wedding rings and his wife's dress.

Casino in Baden

Casino in Baden

Both Tolstoy and Dostoevsky reflected their experiences at German casinos in their respective works, "Anna Karenina" and "The Gambler". Baden-Baden is even considered the third city of Russian literature in terms of the frequency of references to it. The spa town cherishes the memory of its famous Russian visitors - for example, busts of Turgenev, Dostoevsky and Zhukovsky have been erected here.

Wiesbaden and Bad Homburg

These two towns were places that writers would visit for a while, rather than live in for extended periods. Like Baden-Baden, they were locations that lured the visitor with their healing springs and casinos. All three towns claim to be prototypes of the fictional Roulettenburg in which unfolds the plot of Dostoevsky's novel “The Gambler.” In Wiesbaden in 1862 the author played roulette for the first time, and the last occasion he did so was also here - in 1871.

Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Gambler, German edition

Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Gambler, German edition

Dostoevsky's gambling addiction would cause him to lose almost all his money, as well as his free time, in the casino. In 1865, he lost so much money that the hotel he was staying at refused to provide board for him - the writer was given only bread, tea and, occasionally, candles. Dostoevsky had to write to friends asking to lend him money and send it so that the hotel would let him check out. And yet, it was in these straitened circumstances that he began work on one of his major novels, “Crime and Punishment”.

Berlin

Berlin University was famous in the 19th century as a major European academic center. Turgenev dreamed of an academic career in his youth and came to study here because Russian universities didn’t offer sufficiently in-depth courses in his field of interest, philosophy. Having been in the Prussian capital up to 1841, he returned there six years later in pursuit of his inamorata, Pauline Viardot. The Berlin of that time appeared to Turgenev as a somewhat provincial city, but the writer also sensed "major internal changes" there. "Berlin is still no capital; at least, it lacks any trace of the life of a capital city, although you still feel, after spending time here, that you are in one of the centers or focuses of the European movement."

Unter den Linden street in Berlin, 1920s

Unter den Linden street in Berlin, 1920s

A pre-revolutionary atmosphere prevailed in the German Confederation at that time, and it was a change noticed by Turgenev. "People seem to be waiting for something here, everyone is looking to see what will happen. But the beer joints (Bier-Locale [sic] is the name of the rooms where that vile and worthless beverage is drunk) are also filled with the same faces; the horse-cab drivers wear the same unnatural hats; the officers are just as fair-haired and tall, and pronounce the letter ‘r’ just as negligently; it seems that everything is carrying on as before."

Following the 1917 Revolution a new generation of Russian writers began to flock to Berlin, making it one of the largest Russian émigré centers and the literary capital of the Russian diaspora. These included Maxim Gorky, who was subsequently to become the principal bard of the Soviet state; the author of “Doctor Zhivago,” Boris Pasternak; and many others, lived and worked here.

Vladimir Nabokov lived here for 15 years, from 1922 to 1937, publishing his first verses and novels, marrying and becoming a father. Many of his works are set, to one extent or another, in Berlin. According to his biographers, he was not overly fond of the city. In his work, Berlin was always portrayed in somber and muted colors. Here is what Nabokov wrote to his wife: "My darling, among the little side-wishes I can mention this one – an old one: to leave Berlin, and Germany, to move to Southern Europe with you. The thought of yet another winter here fills me with horror. <...> I'd prefer the remotest province in any other country to Berlin."

Dostoevsky, who was in Berlin almost ten times - albeit not for long periods - also found little reason to get excited about the city: "I noticed from the very first glance that Berlin is unbelievably like St Petersburg… Heck, I thought to myself: Was it really worth enduring two whole days and nights rattling around in a railway carriage only to see the same thing I had just left behind me?"

Marburg

In 1736, a trio of Russian students presented themselves with a letter of introduction to distinguished Marburg University professor Christian Wolff. The oldest of them, Mikhail Lomonosov, was to go down in Russian history as a poet, scientist and encyclopedist with profound knowledge in many scientific fields.

Marburg, 1920s

Marburg, 1920s

Wolff noted Lomonosov's abilities, diligence and academic merit, but the adventures of the poet and his fellow-students were not confined to their studies. Discovering the attractions of Marburg's boisterous student life, all three plunged headlong into revelry. They lived it up, threw their money around and got into fights. Because the German students constantly carried swords with them, Lomonosov even took up fencing. In consequence, he was reprimanded by his supervisors in St. Petersburg who did not approve of his spending money on fencing and dancing teachers or on "costumes and vacuous foppishness".

Almost 200 years later, in 1912, the 22-year-old Boris Pasternak was attending the same university. In a letter to his family, he wrote that the city had retained the atmosphere of the period when Lomonosov had been there. "There are no ‘remains’ of the old Marburg here. I am studying in the old Marburg." Marburg could be described as a turning-point in the life of Pasternak the poet: It was here that he gave up plans for an academic career and became a mature writer. A poem whose title bears the city’s name closes this early period in his poetic oeuvre. It is based on the poet's own amorous travails.

During Pasternak's studies in Marburg, he was visited by the daughters of the most powerful Russian tea magnate David Wissotzky. The poet had tutored them in Moscow, not to mention that his father, the famous artist Leonid Pasternak, had painted the portrait of their father.

Pasternak had been in love with the elder sister for many years, and decided to make his feelings known just as they were due to depart, but was rejected. Overcome by his feelings, he jumped onto the footboard of the express train on which the Wissotzky sisters were leaving. The girls had to rescue the poet from the conductor, they paid for his ticket and all three reached Berlin together. Here Pasternak alighted from the train and spent the whole night sobbing in a cheap hotel - and in the morning returned to Marburg.

Badenweiler

This small resort town entered the annals of Russian literature as the place where playwright Anton Chekhov died. The writer, a doctor by profession, had himself suffered from tuberculosis in his youth. Hard work, his financial position, frequent relocations in unfavorable circumstances and also the constant postponement of treatment merely aggravated his condition.

A monument to Anton Chekhov in Badenweiler

A monument to Anton Chekhov in Badenweiler

The 44-year-old writer arrived in Badenweiler with his wife in 1904. His condition improved, but not for long - Chekhov was even asked to move out of his hotel because his severe cough was alarming the other guests. The town had a mixed impression on him. In his letters, Chekhov, on the one hand, spoke highly of the local scenery and the fine living conditions at the resort, but, on the other, complained of boredom and lambasted the Germans (and particularly German women!) for their lack of taste and "German placidity and orderliness".

The writer dreamed of traveling to Italy and made plans for a steamboat trip, but he was never to see them realized: One night, he felt so much worse that for the first time, as his wife recalled, he asked for a doctor. Chekhov addressed the doctor in German, a language he hardly knew, and stated: "Ich sterbe [I am dying]." After that, he smiled at his wife, drank a glass of champagne and died peacefully. The world's first monument to Chekhov was unveiled in Badenweiler four years later.