Why were Chuvash women recognized by SOUND (PHOTOS)?

When we went to visit modern Chuvash people, we were astonished by the adornments of their women. They wore helmets entirely covered with Soviet and old coins. Then, it turned out that these were quite simple variants of their headdresses and necklaces.

Traditional coin adornments of Chuvash women can apparently weigh up to 15-16 kilograms!

A silver cap

Monisto of the Turkic peoples of Russia.

Monisto of the Turkic peoples of Russia.

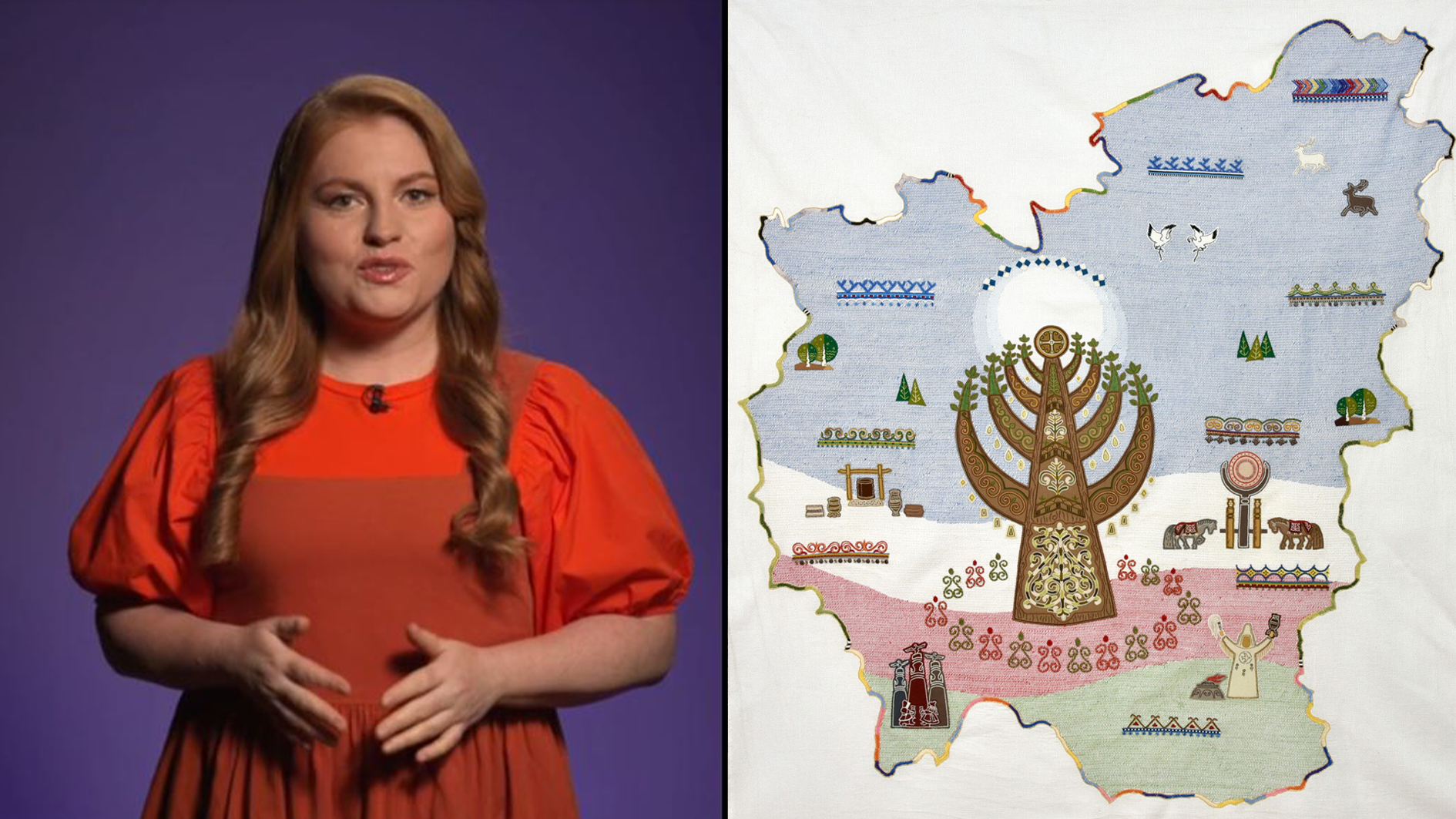

Many ethnic peoples of Russia have used coins for adornment: they’re worn in Udmurtia, Tatarstan, Mari El, Bashkiria. You may be familiar with the word ‘monisto’ – a necklace made of coins. But, it was in Chuvashia where such women’s decorations reached incredible proportions.

The main piece was the handmade headdress. An unmarried woman’s cap, a ‘tukhya’, looked like a warrior’s helmet; a married woman’s cap, a ‘hushpu’, had an open top and a long “tail”. This heavy tail helped keep one’s back straight.

Chuvash women, archive photos.

Chuvash women, archive photos.

These caps were generously adorned with heavy silver coins; if there were not enough coins, “tokens” were used, a coin imitation. The best coins were placed near the temples and they produced the clearest jingle when the woman walked. Only coins that were out of circulation were utilized. In museums and in old photos one can clearly see foreign coins that ended up in Chuvashia, most likely, by way of the Volga River – the main trade route in the past. Apart from coins, beads and small shells were also used in the headdresses. They were a sign of wealth at some point, as well.

“A girl put on a tukhya upon entering the child-bearing age, thus, showing that she was ready for marriage and for procreation,” chief of the Museum of Chuvash Embroidery in Cheboksary Nadezhda Selverstrova says. A tukhya was worn at all times; necklaces made of coins (they were called ‘chapchushki’) and earrings (‘alga’) could be also worn with it.

During a marriage ceremony, a young woman would put on a hushpu, passing her tukhya to her younger sisters. “A hushpu was worn on holidays,” Nadezhda explains. “When a woman grew older, she passed her hushpu to her oldest daughter, herself wearing only a surpana headscarf. If a woman wore a jingling hushpu, it was as if she was saying that she was still able to bear children.”

An old cap from the Museum of Chuvash Embroidery.

An old cap from the Museum of Chuvash Embroidery.

Apart from headdresses, Chuvash women wore ‘shulgeme’ necklaces. By their look, they seemed like a purse or a sign, created entirely from coins with a decorative binding in the middle (often a patrimonial sign was depicted there. We talked about them in more detail in our article about Chuvash embroidery). Earrings called ‘alga’ were also made from coins; they were also heavy and jingled.

Protection and an investment

Such decorations, as considered in the old times by the Chuvash people, were meant to protect from dark forces, as Nadezhda says. “Usually, women were married off to distant lands to exclude closely related marriages; arriving at a new place, a woman needed to both show her status and protect herself from new, unfamiliar spirits.” In the traditional Chuvash faith, everything living had its own spirits, be it a spring or a forest.

Old Chuvash coin jewelry.

Old Chuvash coin jewelry.

The coins by themselves didn’t possess any protective qualities, but the silver they were made from did. Today, it’s scientifically proven that this metal is capable of eliminating bacteria. To the contrary, golden coins and tokens were almost entirely absent in Chuvash adornments.

However, there is also a fantastic legend of the origins of the “helmet” with coins. Allegedly, Amazonian women, famed for their military merits, were among the distant ancestors of Chuvash women. Their last representatives allegedly settled in Povolzhye and their chainmail became the national costume of the Chuvash people. By the way, the costume Chuvash men wear has no coins.

Why did they stop wearing coins?

The folk costumes seem like a thing from the ancient past only at first glance. In reality, regular people deep in Russia began wearing modern outfits only a few decades ago. Before, everything was sewn (or even woven) by hand.

A girl from Cheboksary in a national costume.

A girl from Cheboksary in a national costume.

The Chuvashs were very fond of their silver adornments that were passed from one generation to another. But, today, they’re almost entirely extinct – all because, during industrialization and dekulakization, in the early Soviet years and during the Great Patriotic War, the Chuvashs gave their coins to the government. From the proceeds, machinery was purchased – from tractors to tanks. During the years of famine, coins were also exchanged for food.

Members of amateur art activities state farm "Znamya", Chuvashia.

Members of amateur art activities state farm "Znamya", Chuvashia.

Perhaps, the last of such historic decorations can be seen only in very remote Chuvash villages or in ethnographic museums. “People bring their family adornments to us so they can be kept safe,” Nadezhda says.