What Pushkin, Tolstoy & Dostoevsky thought about the tsars

Alexander Pushkin – from hate to love

Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Alexander Pushkin

Orest Kiprensky. Portrait of Alexander Pushkin

The leading Russian poet had a special relationship with authorities. In 1834, Pushkin wrote: “I’ve seen three tsars: the first ordered my cap to be taken off me and chided my nanny about me; the second one didn’t favor me; I don’t wish to change the third one for a fourth one, despite him making me a kamer-page in his old years – one doesn’t seek good from good.”

Let’s decipher this. The first tsar was Paul I and he saw Pushkin only as a baby. The poet was born in 1799, while Paul was killed in 1801. That being said, Pushkin in his ‘Ode to Liberty’ hints that the murder took place with the silent consent of the tsar’s son and heir – Alexander I.

Vladimir Borovikovsky. Portrait of Paul I

Vladimir Borovikovsky. Portrait of Paul I

The second tsar was Alexander himself. The relationship of young and hot-blooded Pushkin with him was not good at all. For freethinking poems, the emperor sent the poet into a southern exile and then locked him up in exile at his family estate, Mikhailovskoye. However, this “saved” Pushkin from participating in the Decembrists’ revolt, in which many of his friends participated, with many of them, in the end, being sentenced to hard labor in Siberia. The poet infinitely empathized with them and wrote reassuring poems:

“Your heavy chains, long overdue,

Will drop as jails collapse and freedom

Shall greet you at the gate as freemen.”

George Dawe. Portrait of Alexander I

George Dawe. Portrait of Alexander I

In ‘Eugene Onegin’, Pushkin really harshly “thrashes” Alexander, calling him “a ruler weak and wily” and “a baldish fop”. Pushkin considers Alexander’s victory over Napoleon a “chance” fame. The Russian emperor’s behavior in that war and his cowardice were often ridiculed by the poet in epigrams.

The third tsar that Pushkin saw was Nicholas I. It was believed that the emperor was a poorly educated martinet; however, he highly praised Pushkin and kept him close. Nicholas, in essence, was the poet’s personal censor and read all his works before publication. Aside from that, the emperor made Pushkin a court historiographer, gave him access to archives and allowed him to work on the History of Pugachev’s revolt and other topics that interested him.

Franz Krüger. Portrait of Nicholas I

Franz Krüger. Portrait of Nicholas I

Nicholas promoted the poet to the lowest court rank of ‘kamer-page’ (kamer-yunker, in reality), which the already-famous 34-year-old Pushkin perceived as a humiliation, but it provided him with a salary and various privileges. There were also piquant moments in the relationship of the poet and the tsar – there were rumors going around that Nicholas was fond of Pushkin’s wife and that the latter was terribly jealous.

The poet had a special attitude towards Peter the Great, to whom he dedicated his poem ‘The Bronze Horseman’, in which he, at the same time, admired Peter’s power and greatness and made a claim against him for how harsh he was to his people and his country.

Besides, Pushkin was a great-grandson of Abram Hannibal, an Ethiopian, whom Peter took into his service and for whom he was a godfather (and gave him his patronymic name). Pushkin wrote an unfinished story about this titled: ‘The Moor of Peter the Great’.

Pushkin ruminated on tsarist power a lot and reimagined it in his works. In his tragedy ‘Boris Godunov’, as an example. In his story ‘The Captain’s Daughter’. Pushkin turned to the figure of Catherine the Great, depicting her as a benevolent and wise empress.

Leo Tolstoy – all rulers are ‘stupid and dissolute’

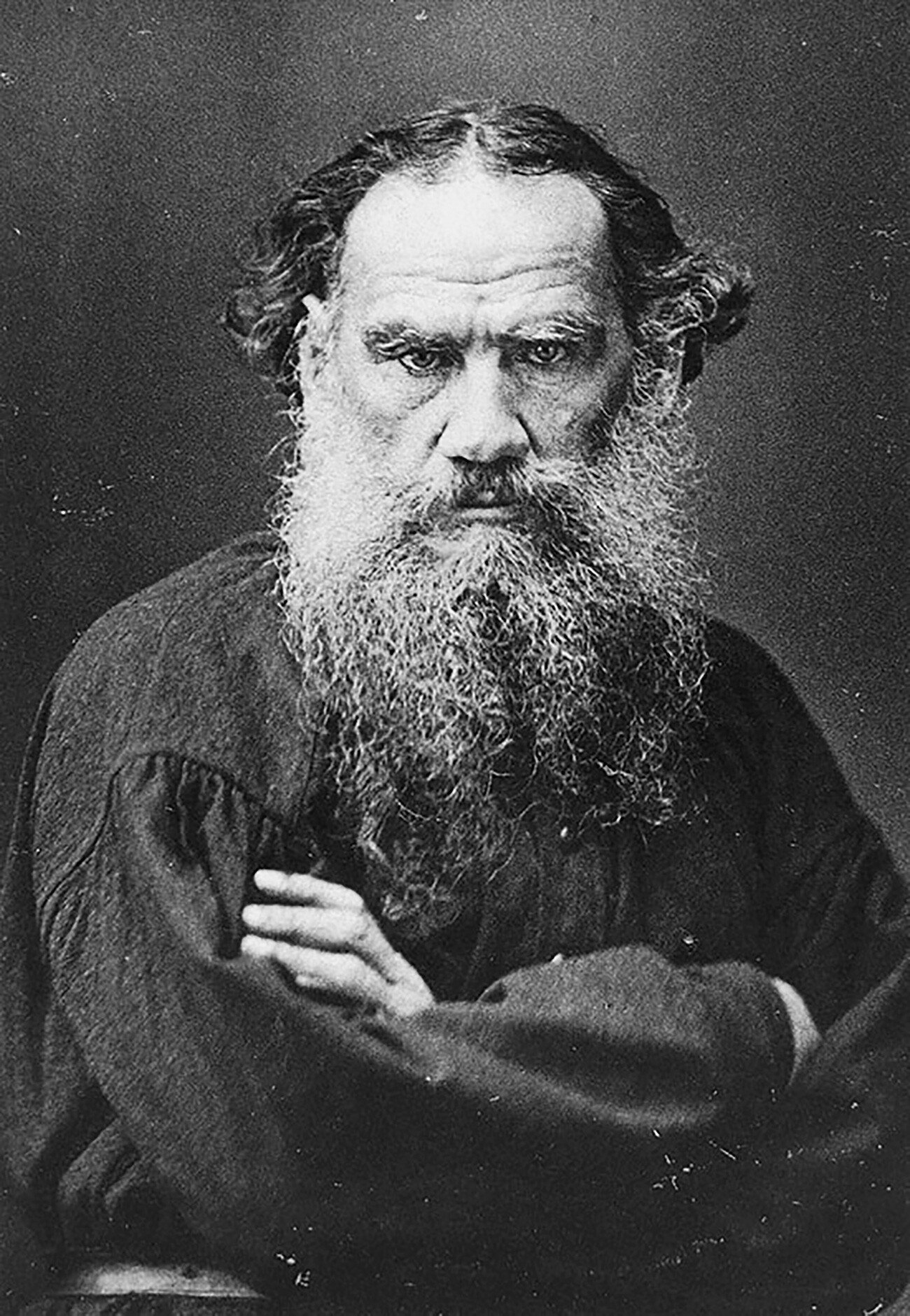

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy

Leo Tolstoy paid a great deal of attention to Alexander I in his novel ‘War and Peace’. He created an image of a regular person with a variety of different qualities, including pettiness, pride and sensitivity (Tolstoy vividly depicted how the emperor felt faint when he saw the wounded). It seems that Tolstoy empathized with the figure of Napoleon much more and he doesn’t believe Alexander ‘the Liberator of Europe’ to be a great master of destinies, in reality. Along with that, the writer showed with what reverence the Russian people treated their ruler, how amazed they were with his presence alone.

Actor Viktor Murganov as Alexander I in the Oscar-winning film "War and Peace"

Actor Viktor Murganov as Alexander I in the Oscar-winning film "War and Peace"

Despite this, Tolstoy can actually be called an anarchist – with some exceptions. He didn’t recognize and was not afraid of any authority and directly exposed the Russian authorities. Tolstoy believed the state to be a thief who took away the right to use the land from a person who was born on this land.

The entire history of Europe, according to Tolstoy – is the history of stupid and dissolute rulers, “killing, despoiling and, most importantly, corrupting their people”. No matter who occupied the throne, the same thing repeated itself – death and violence against people. According to the writer, the “wicked, worthless, ruthless, immoral and, most crucially, deceitful people” are always in power. As if all these qualities are a requirement for being in power.

In his article ‘The One Thing Needed. Concerning State Power’ Tolstoy quite rudely thrashes Russian tsars, branding Ivan the Terrible “mentally ill”, Catherine the Great “a German woman of shamelessly wanton conduct” and Nicholas II, for example, “a hussar officer of limited intellect”.

Viktor Vasnetsov. Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible

Viktor Vasnetsov. Tsar Ivan IV the Terrible

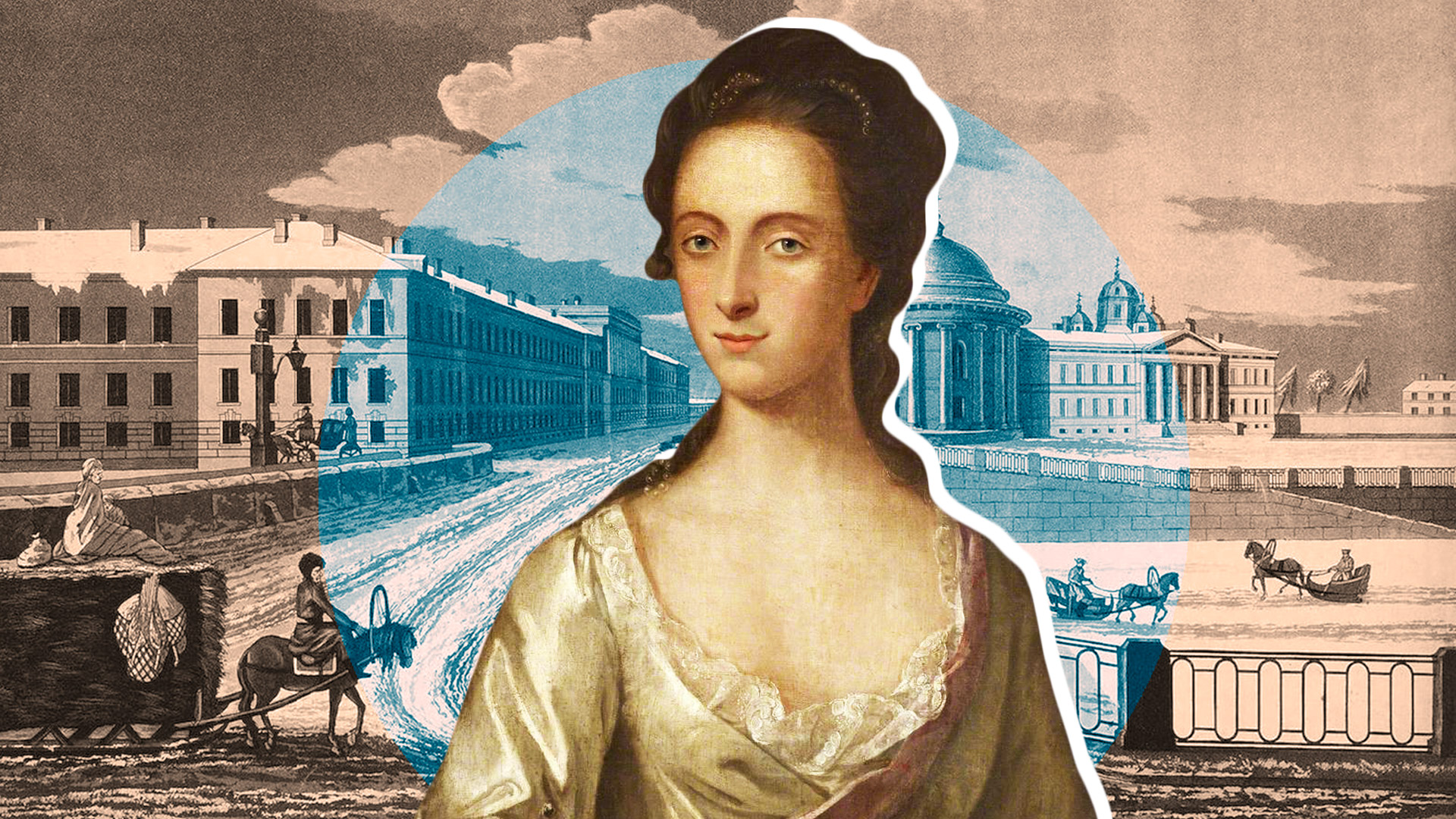

Alexander Roslin. Portrait of Catherine the Great

Alexander Roslin. Portrait of Catherine the Great

N.F.Yash. Portrait of Nicholas II

N.F.Yash. Portrait of Nicholas II

The writer calls Alexander III – who, by the way, highly praised the talent of Tolstoy – “stupid, rude and ignorant”. Alexandra, the beloved aunt of the writer, for example, was a lady-in-waiting of Empress Maria Feodorovna, Alexander III’s wife. The influential relative contributed to the fact that Leo Tolstoy wasn’t punished for his seditious novella ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’. The work was simply banned; but, the emperor spared the writer.

Fyodor Dostoevsky – a committed monarchist

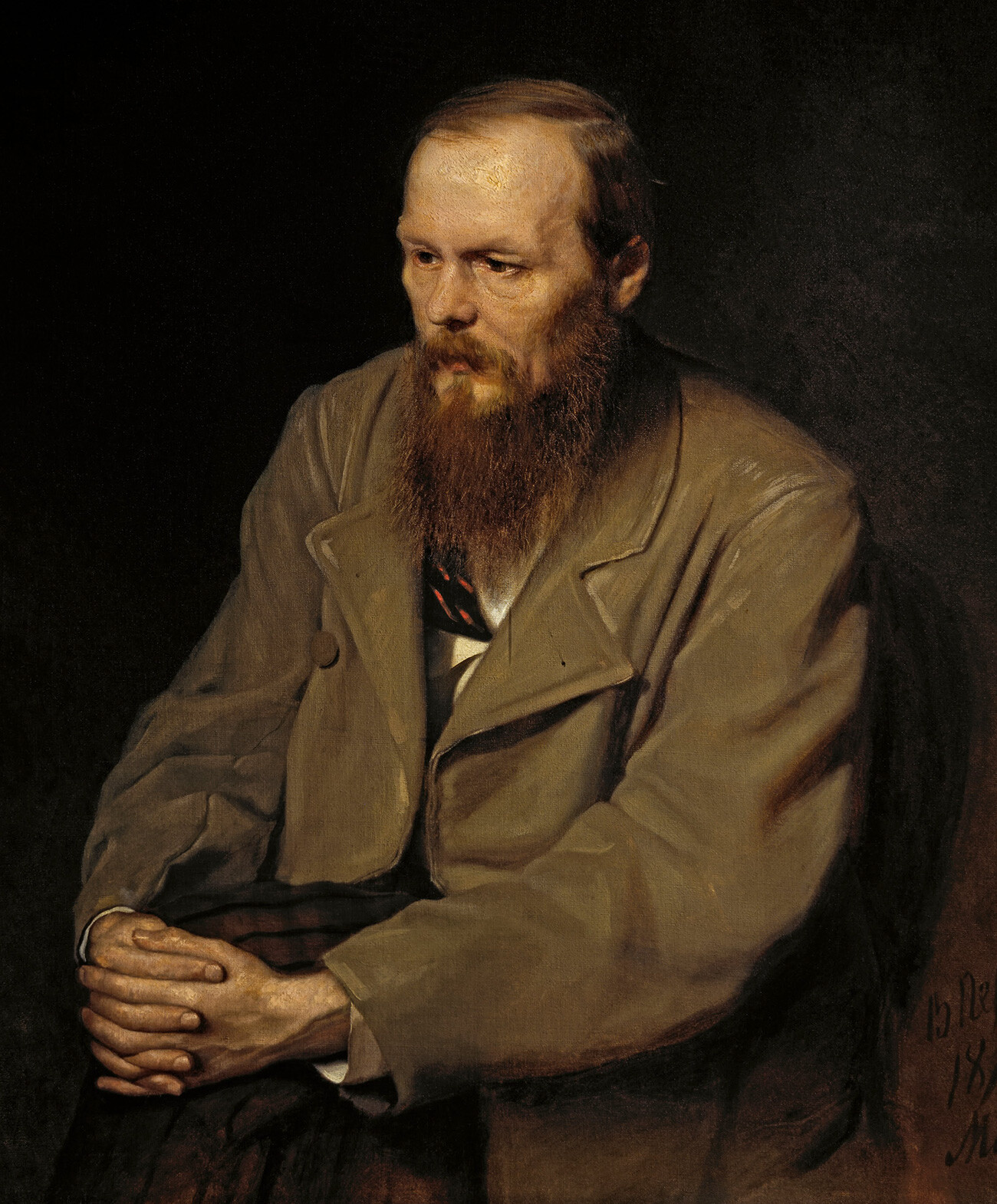

Vasily Perov. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky

Vasily Perov. Portrait of Fyodor Dostoevsky

Dostoevsky’s relationship with the authorities had the most dramatic turn. In his youth, under the influence of critic Vissarion Belinsky, Dostoevsky ended up in the revolutionary-minded Petrashevsky Circle; during one of their meetings, he read the banned ‘Belinsky’s letter to Gogol’, where he described life in Russia in the most grim tones.

In 1849, he was arrested for this, among other members of the Petrashevsky Circle. After eight months in prison, the writer was sentenced to death. On the scaffold, it was announced to Dostoevsky and other members of the Petrashevsky Circle that Emperor Nicholas I had pardoned them and had replaced their punishment with eight years of hard labor in Siberia. One of the sentenced went insane soon after from such a staging of the execution; the mental state of Dostoevsky himself was also affected.

Yegor (Georg) Botman. Portrait of Nicholas I

Yegor (Georg) Botman. Portrait of Nicholas I

Because of all these events, the writer rethought all his values. He joined the Pochvennichestvo movement, believed in “Russian distinctiveness” and the importance of the Russian idea and became a committed monarchist. He vividly expressed the harmful nature of revolutionary ideas and revolutionary-minded youth in his novel ‘Demons’.

Dostoevsky also had direct contacts with the imperial family. Alexander II, who officially announced that the Petrashevsky Circle had been pardoned, invited the writer many years later to have a conversation with his sons Sergey and Pavel. Dostoevsky never met the emperor himself, but had lunch with the grand princes three times, expressing to them his view of the future of Russia. He also talked about political topics.

Nikolai Lavrov. Portrait of Alexander II

Nikolai Lavrov. Portrait of Alexander II

The writer really liked the figure of the heir to the throne – future Alexander III; the latter also highly praised Dostoevsky and especially his novel ‘Demons’. In 1880, the future emperor received the writer in his palace. Dostoevsky’s daughter, Lyubov, remembered this event: “It was very characteristic that Dostoevsky, an ardent monarchist in this period of his life, didn’t want to obey the etiquette of the court <…>. Perhaps, this was the only time in the life of Alexander III when he was treated like a mere mortal. He didn’t get offended and later spoke of my father with respect and sympathy.”

Alexander called the death of Dostoevsky “a big loss”; a month later, the terrorists the writer was so concerned about, killed his father, Emperor Alexander II, and he ascended to the throne.

Ivan Kramskoy. Portrait of Alexander III

Ivan Kramskoy. Portrait of Alexander III

Dostoevsky also had the idea for a poem he had tentatively titled: ‘Emperor’, in which Ivan VI was supposed to become the main character, ‘the baby emperor’, overthrown by Peter the Great’s daughter Elizabeth and imprisoned for 20 years (after which he was killed).