Zhostovo: All you need to know about painted lacquer trays

During World War II, all of Russia’s iron was sent to the front line, but in the village of Zhostovo, just outside Moscow, a craftsman named Andrei Gogin continued to teach girls the old art of iron tray painting on… American cans. They came as part of humanitarian shipments. While all the men went to the front line, the young girls stayed in their households: they went to the forest to gather firewood, heated their homes and studied. So even in the most difficult years for the country, masters tried to preserve and pass on their knowledge of the old Russian craft.

Zhostovo is an old village in Mytishchi near Moscow, known since the early 19th century. At the time, Zhestovo, as it was formerly called, was part of the Troitskaya volost in Moscow Region. It was thanks to serf peasant Philip Vishnyakov that it, at some point, attracted the attention of the entire Russia.

Vishnyakov worked as a carriage driver at a rather large free tobacco factory owned by a merchant named Korobov in the neighboring village of Danilkino (now called Fedoskino). It was there that painted lacquer papier-maché boxes started to be produced. Fedoskino lacquer miniature is also a traditional old Russian craft. Korobov bought the lacquer coating recipe in Germany, with Vishnyakov later borrowing the technique.

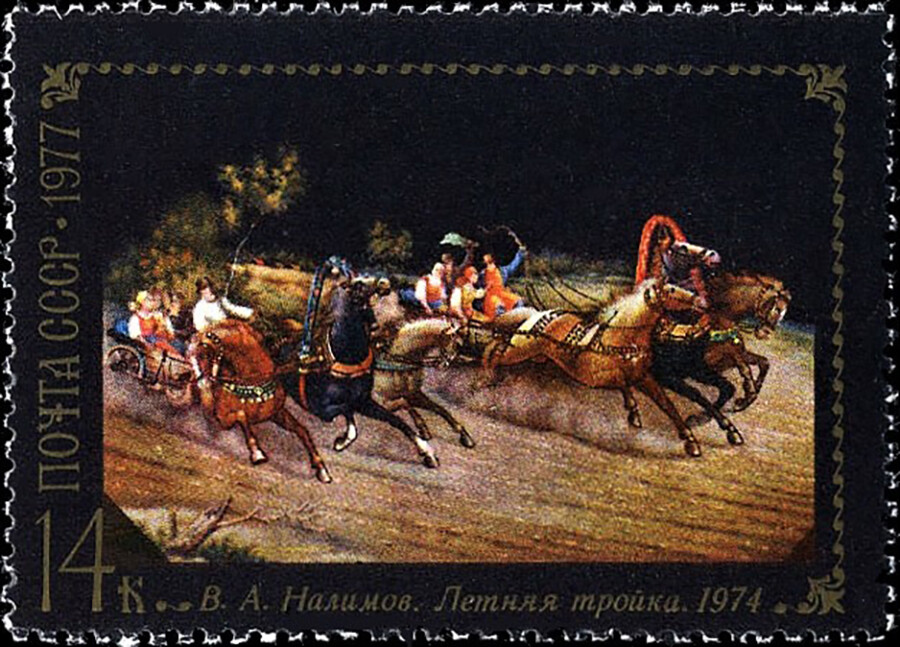

Fedoskino stamp

Fedoskino stamp

“Let’s call it a collaboration”

In his village of Zhostovo, he opened a “lacquer workshop”. At first, they also worked with papier-maché, manufacturing snuff boxes, jewel boxes and trays decorated with copies of famous paintings or drawings popular at the time. The business was booming: a store opened its doors to customers in the center of Moscow, while, back in Zhostovo, the peasant put his brother in charge of their ‘Vishnyakov brothers’ manufacture of lacquered metal trays, biscuit jars, trays, papier-maché boxes, cigarette cases, teapots and albums’ business.

“Papier-maché used to be like stone. It’s for a reason that a semi-finished product takes six months to prepare. First, boxes were painted, then trays were made of papier-maché . They are preserved in the Russian Museum of St. Petersburg. The boxes were black, said to be resembling the soil, which flowers grow in,” says Larisa Goncharova, Russia’s honored artist and Zhostovo’s hereditary master.

Soviet stamp from Zhostovo.

Soviet stamp from Zhostovo.

In 1825, Osip Vishnyakov’s son opened an independent workshop in the neighboring village of Ostashkovo, where he focused on the production of trays not of papier-maché, but of metal. The younger Vishnyakov is said to have met Ural masters, who sold iron trays at a fair and, like his father, he supposedly borrowed the idea from them. “Let’s call it a second ‘collaboration’,” laughs Larisa Goncharova.

The metal trays were of a simple rounded shape, initially modestly decorated on their sides. Later, they were painted in the “Ural style” - with flowers and “herbs”, with a dark background and lacquer coating preserved, which made it possible for the trays to last for a long time.

Nizhny Tagil painting.

Nizhny Tagil painting.

With the abolition of serfdom, the Vishnyakovs had quite a bit of competition: family workshops that produced the same painted iron trays started to emerge in Zhostovo, neighboring Ostashkov, Khlebnikov and other villages of the Troitskaya volost.

Learning on tin cans

“Mytishchi is derived from the word mytnya, which means ‘customs’. Boats loaded with goods sailed down the Klyazma River to Moscow and they stopped at the customs checkpoint in Mytishchi. There were a lot of tea houses around, where merchants drank tea. And it certainly was served on trays,” says Larisa Goncharova, explaining their popularity in Zhostovo in the 19th century.

Today’s Mytishchi is adjacent to Moscow: thanks to the proximity to the big city, craftsmen from the Troitskaya volost easily found a market outlet at local fairs to sell their goods. By the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th century, Zhostovo, as well as other folk crafts, went into decline, due to the beginning of industrialization and World War I. Men left for the front line, while women held the fort.

Girls studying the Zhostovo craft.

Girls studying the Zhostovo craft.

By 1930, the situation had changed: the craft began to be revived and workshops were united into guilds. But then World War II intervened. “That’s when famous Zhostovo master Andrei Pavlovich Gogin picked six girls, including my mother Nina, and began to teach them to paint on cans, so that the craft wouldn’t die,” Goncharova tells the story of her family.

In the 1940s, an art school opened in the neighboring settlement of Fedoskin, where there was a Zhostovo painting department and, in the 1960s, a guild called ‘Metallopodnos’ (literally ‘metal tray’) became known as the ’Zhostovo Factory of Decorative Painting’. After the collapse of the USSR, it was transferred into private hands and it is still in operation today.

“The state supports the factory, they enjoy great benefits and investments; separately, a museum was opened and, even in winter, tourists visit by bus. Sometimes, trays are bought, sometimes - not; but, every day, there are guided tours at the factory. At times, six to eight buses a day arrive at the museum, especially on weekends, bringing children,” Goncharova rejoices.

Siberian squirrel’s ear

The Zhostovo tray technology allows the products to serve more than one family generation. And though all secrets are already known, there are nuances without which a tray cannot be referred to as “Zhostovo-manufactured”. A pressed or forged shape is first degreased by removing the film from the metal. If this is not done, it will corrode and, over time, the tray will be damaged.

Then, a black oil primer and background are added, the item is cleaned and passed on to an artist. They paint the tray “in two steps”. The first layer, or as artists call it, “zamalyovok”, is applied with a bleached paint. The tray is then left to dry overnight in an oven. The second paint layer is then applied.

Here is how the artist herself depicts the intricacies of the work:

“All the paints are oil ones, with the round brushes made from the hair of the Siberian squirrel. These are special brushes, knitted by hand and specially ordered for Zhostovo masters. There are no such brushes for sale, they are too expensive. The brush strokes have to be soft - something that can be achieved only with a squirrel-hair brush. The strokes must be applied in one breath. It’s impossible to describe it, to learn how to do it, one has to sit beside the master and feel how their brush stroke dances, to see where to press it, where to lift the brush, how to hold it and adjust. You just can’t learn how to do it on the Internet. A Zhostovo stroke is different from all the others.”

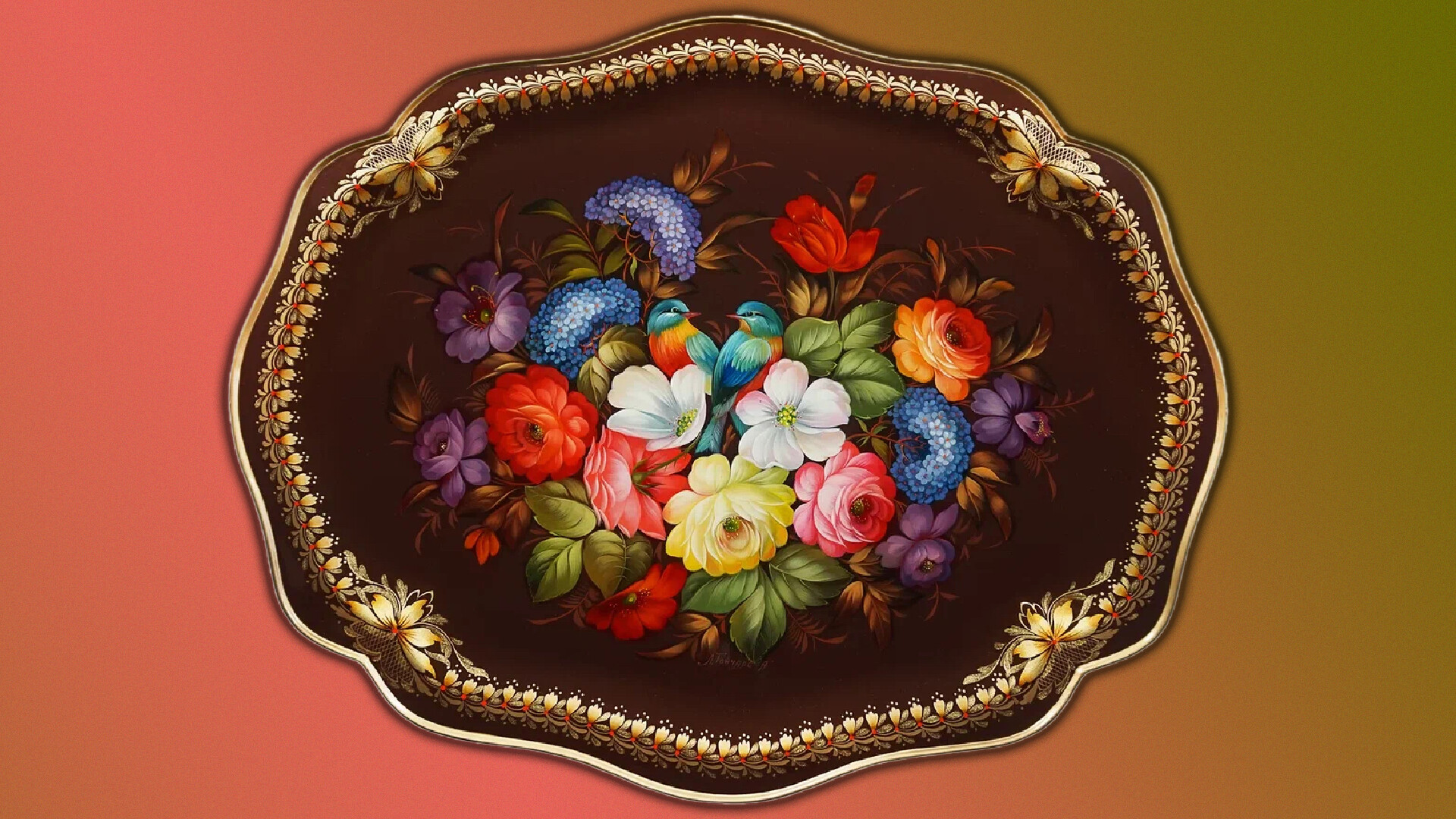

Goncharova’s tray with the author’s signature.

Goncharova’s tray with the author’s signature.

The pattern is applied on the tray surface wet from linseed oil. Next come two coats of varnish: it fixes the paint and makes it glossy.

One of the trays made by Goncharova.

One of the trays made by Goncharova.

“In earlier times, it was boiled based on a secret recipe, which was never revealed, but my granddad knew it,” Goncharova says, adding that, nowadays, all craftsmen use Russian or American-produced lacquers.

As opposed to the Khokhloma painting of wooden dishware, there are no real examples in Zhostovo tray painting: the artists paint “out of their heads”. Yet, the traditional recognizable motifs are still preserved: everyday life scenes, Fedoskino troikas, landscapes, birds, but, most importantly - bouquets. They boast all kinds of flowers, from creepers to roses, which are considered to be “the queen” of Zhostovo art. The most common composition is center-oriented. Three or four flowers are placed in the middle, with buds and smaller flowers put closer to the edges. “Such a bouquet typically has three leaves marking the bottom. The whole composition is completed with a binding - thin grass, which is the darkest in color. Zhostovo artists strove for beauty, especially given the fact that winter lasts six months,” explains Goncharova.

Three minutes to the factory across a potato field

Zhostovo lies on a peninsula: it is almost entirely surrounded by water and communication with the “mainland” has always been a bit of a challenge. Only in the 1960s was a bus stop built five kilometers away from Zhostovo, along the new route to the Klyazma sanatorium. Because of such a location, mostly locals worked at the factory. The heirs of craftsmen’s dynasties - the Antipovs, the Mozhaevs, the Leontievs, to name a few - still live in Zhostovo. Larisa Goncharova is from the Belyaev dynasty: her mother, grandmother - all in the male lineage - were artists and lived there.

Larisa Goncharova with her mother Nina.

Larisa Goncharova with her mother Nina.

“In Soviet times, locals worked at the factory: blacksmiths and stampers, lacquerers, painters, and ornamentalists. Young people were coming out of the Fedoskino school. Few stayed at the factory: everyone wanted to earn money straight away and it took years of experience to become skilled. It is not an easy technique. Now we only have two blacksmiths left at the factory. They are both over 70, but they still continue doing their job. Artists also order molds from them, because they can forge anything. The work is labor-intensive and no one even wants to learn how to do it. I don’t know what will happen after them.”

Naturally, the price of a tray depends not only on how the mold is made: it can easily be distinguished from a fake one by the bent edge. No less important is the popularity of the artist: there are ordinary ones and there are those who made a name for themselves. The tray comes with a certificate featuring who made it. “Yet, only one honored artist still remains at the factory - chief artist Mikhail Lebedev,” says Goncharova.

The cheapest tray in the factory store costs about 2,000 rubles (approx. $28). But, you can spend up to 180 thousand (approx. $2,500) for works by a reputable artist.

In 2003, Larisa Goncharova, just like her mother Nina Goncharova, received the title of ‘honored artist’. Larisa worked at the factory until her retirement: "The factory is right behind my house, three minutes away across the potato field”.

In 1996, she became self-employed and opened her own studio.

Nina Goncharova at work.

Nina Goncharova at work.

Starting from then, a couple of times a year, she also traveled abroad to teach - to America, Australia, Germany and Italy:

“I taught for 15 years in America. Russian crafts are very popular there. It’s certainly not possible to teach anyone how to make Zhostovo trays in a three- to four-day course, but they were able to paint one item in this time. You have to live on this soil to paint in the Zhostovo technique.”