How food prices decreased under Stalin

Almost no one is alive today in Russia who fully remembers Stalin’s consumer price reductions, as well as the incredible surge of optimism among the population that accompanied such developments. While the capitalist world had become accustomed to living with consistently rising prices and saw them as a sign of economic growth, the USSR saw things differently. With its planned economy, Moscow measured improvement in public well-being not with prices rising but rather with them falling. So, what was happening in the late 1940s: was it a Soviet propaganda trick, or a real economic miracle?

Surviving on food ration stamps

"Who gets the national income? In capitalist countries, the lion's share goes to the exploiters; in the USSR, to the workers".

"Who gets the national income? In capitalist countries, the lion's share goes to the exploiters; in the USSR, to the workers".

In 1929, the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, said: “We don’t have an unregulated setting of prices on our markets, as is usually the case in capitalist countries. We mostly determine bread prices. We determine consumer goods’ prices. We are trying to pursue a policy of reducing the cost of produce and lowering prices for consumer goods, striving to maintain the stability of prices for agricultural products.”

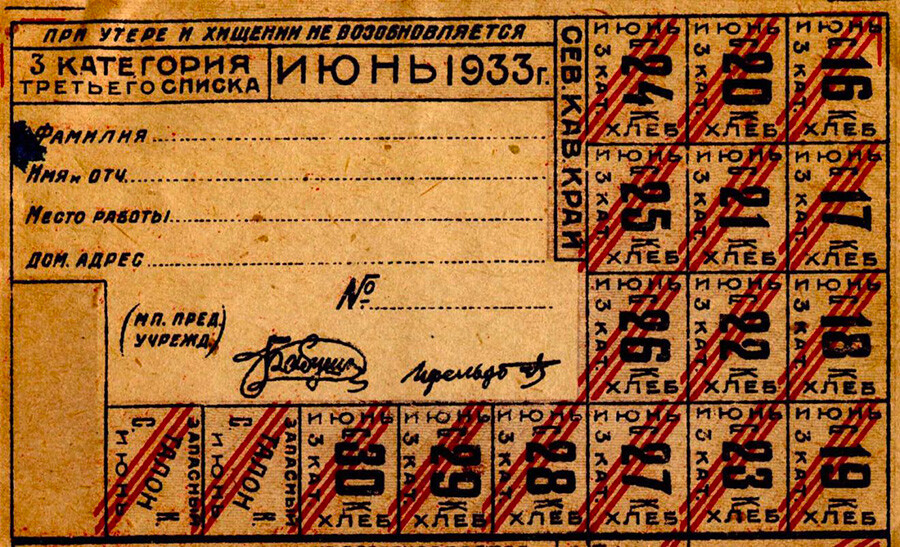

Food ration stamps, 1933.

Food ration stamps, 1933.

At the beginning of the 1930s, Stalin advocated the abolition of food ration stamps that were in place at the time. Prices were high, and the peasants who sold their produce at public markets found this situation advantageous for themselves - they could set high prices for their goods. The abolition of food ration stamps in 1935 led to a temporary price drop, but during the war years the country went back to the rationing system of food and consumer goods. This continued until 1947.

In 1947, more than a third of the USSR’s population (62.8 million people) was on state welfare to receive free bread. The food ration stamp system was widespread, but there was also a free market. As such, the country had a state-determined price level that was fixed by food ration stamps, as well as commercial prices on the free market. At some point, the authorities decided that it was time to step away from food ration stamps and establish unified prices for all food items and goods.

The 1947 monetary reform

A money exchange, 1947.

A money exchange, 1947.

By 1947, both village dwellers who sold their produce at public markets, as well as food speculators, had earned and accumulated large amounts of money. According to data for 1943-1944, the share of income from “the exchange of goods and services between population groups” amounted to 56% of the total sum of the entire population’s income. The state realized that a part of the population had accumulated a significant amount of money, and this wealthy group wasn’t the working majority, the welfare of which the state most cared about. So, the authorities came up with a way to lower the cost of living for most people at the expense of the savings of those better off.

In December 1947, the monetary reform began at the same time as the abolition of food ration stamps, the transition to unified prices, and the issuing of new banknotes. The state released a new ruble, which was exchanged at a rate of 1 new ruble for 10 old ones.

Deposits at state-owned Sberkassa that totaled under 3,000 rubles, which characterized more than 80% of the population, were exchanged 1-to-1. Anyone with a deposit of more than 3,000 rubles and up to 10,000 rubles, was given two new rubles for three old rubles. If your deposits were greater than 10,000 rubles, then two old rubles were exchanged for one new ruble. As such, wealthy citizens came away as the big losers in the monetary reform.

Candy store in Moscow, 1949.

Candy store in Moscow, 1949.

“To curb the inevitable negative emotions of Soviet citizens due to the loss of a part of their savings, the abolition of food rationing stamps and a mass reduction of retail prices preceded the monetary exchange,” concluded the authors of the academic research book, The 1947 monetary reform and its role in restoring the national economy of the USSR, (edited by R. M. Nureev, M. A. Eksindarov; Moscow, KNORUS publishing house, 2019).

After the abolition of ration stamps, a unified price system for goods was established – at a medium between state prices and commercial prices. The prices for bread, flour, and pasta were lowered 10-12% (relative to state prices), since they were essential for the population. Prices for many other goods ended up being higher than the previous prices set by the state. As a result, except for a limited group of food products, the price of food and consumer goods in shops actually remained high, and even higher than pre-war prices.

Some consumer goods remained in warehouses, collecting dust. To change this situation, in April 1948 the state reduced the prices of cars, motorcycles, sewing machines, watches, music players, and other goods by 10-20%.

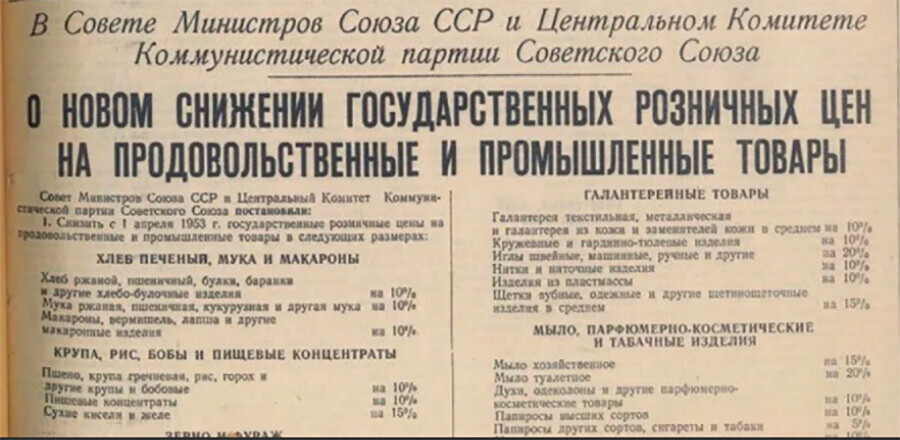

Even after this price reduction, in monetary terms these prices still remained high for regular people. So, in March 1949 they were reduced yet again. Subsequently, prices were lowered every spring – the final one happened in spring 1953 after Stalin’s death. In different years, the price reduction impacted different groups of goods. For example, in April 1953, there was a very noticeable price reduction of vegetables and fruits for most people – almost slashed in half. Meat prices were lowered 15%, and prices for consumer goods were lowered 5-30%.

Was this price reduction an ‘economic miracle’?

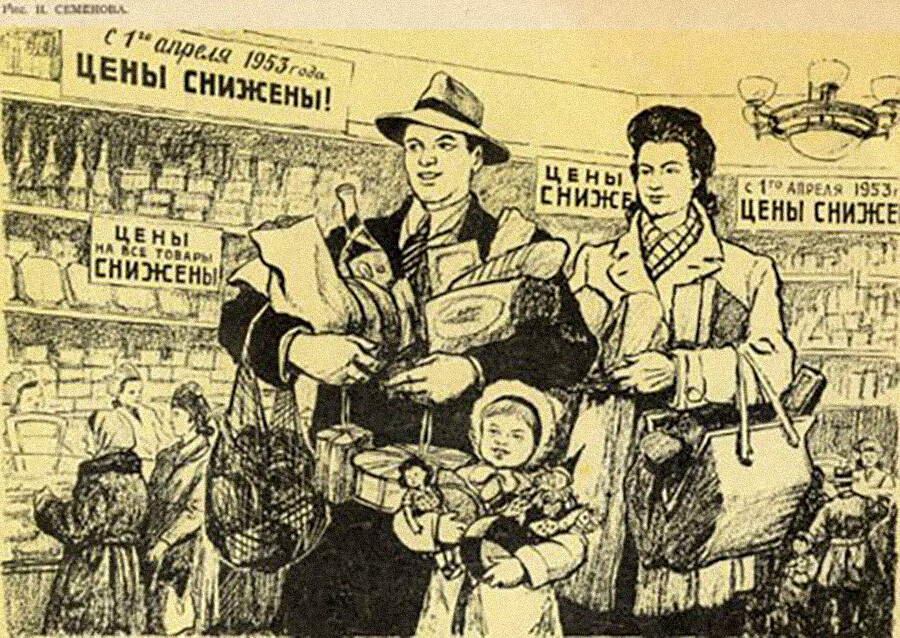

Newspaper cartoon: "Lower prices from April 1, 1953!"

Newspaper cartoon: "Lower prices from April 1, 1953!"

Soviet newspapers dedicated entire pages to the price reduction, telling citizens about economic well-being and the accessibility of goods. On April 2, 1953, the front page of Pravda praised the sixth price reduction: “The current price reduction, as all the previous ones, is the result of the achievements reached by our people under the leadership of the Party in developing industrial and agricultural production; it’s the result of the systematic growth of labor productivity and the reduction of produce costs. The Soviet people are directly interested in the growth of their labor productivity, since they know that it reinforces the economic might of the USSR and raises the living standards of the working people.”

Front page of 'Pravda' newspaper, April 2, 1953.

Front page of 'Pravda' newspaper, April 2, 1953.

Indeed, one of the reasons for such long-term deflation was the post-war reconstruction of industry, the subsequent increase in production, and the reduction of the cost of goods that Soviet working people were eager to obtain. During this time the country had a system of bonus payments for employees, and special labor collectives aimed for exceptional work results that led to the reduction of the cost of goods.

Labor productivity in industry grew 1.7 times from 1940 to 1953; while in construction it grew 1.5 times. The cost of goods was falling – so the price reduction also seemed logical.

However, according to Yakov Mirkin, Professor of Economics, the main basis for this reduction was the inflated pre-war prices; as well as the confiscation of money from the population during the exchange of old rubles for new ones, including with the help of unfavorable conditions of exchange when closing a deposit.

“The population exited the monetary reform with unified state prices, which were 2.56 times higher than the pre-war prices – along with the liquidation of 90% of savings in cash that people had on hand, 16% of deposits, and more than 60% of savings in state bonds,” Mirkin says.

Also, as he notes, the threefold growth of real national income at this time, which defied the laws of economics, outpaced industry growth. But after the monetary reform that benefited the state, it became possible for the state to increase the growth of national income top down by increasing salaries or through direct reduction of retail prices. Nikita Khrushchev came to power in 1953, after Stalin’s death, and he began new economic reforms and ended Stalin’s practice of price reductions.

READ MORE: How the USSR traded with the West despite the Iron Curtain