How Nizhny Novgorod became the trade center of the Russian Empire

“St. Petersburg is Russia’s head, Moscow is its heart and Nizhny Novgorod is its pocket.” This old Russian saying is probably the most succinct way of explaining the meaning and importance of the trading that took place in Nizhny Novgorod.

Why did Nizhny Novgorod become a center of commerce?

The city is very conveniently located at the confluence of two major rivers, the Volga and Oka, which run across the whole of Russia and flow into the Caspian Sea. In addition, the Volga was the only arterial waterway linking the West with the East. Nizhny Novgorod, moreover, was on the railway network, so one could travel to the Caucasus, Persia, Turkey, Central Asia and even India and China from there. Thanks to its geographical position, the city had always been a thriving trade hub and archeologists have found Arabic and Byzantine artifacts proving that it had trading links with the East as early as the 13th-14th centuries. The first documented fairs and gatherings of merchants go back to the 16th century.

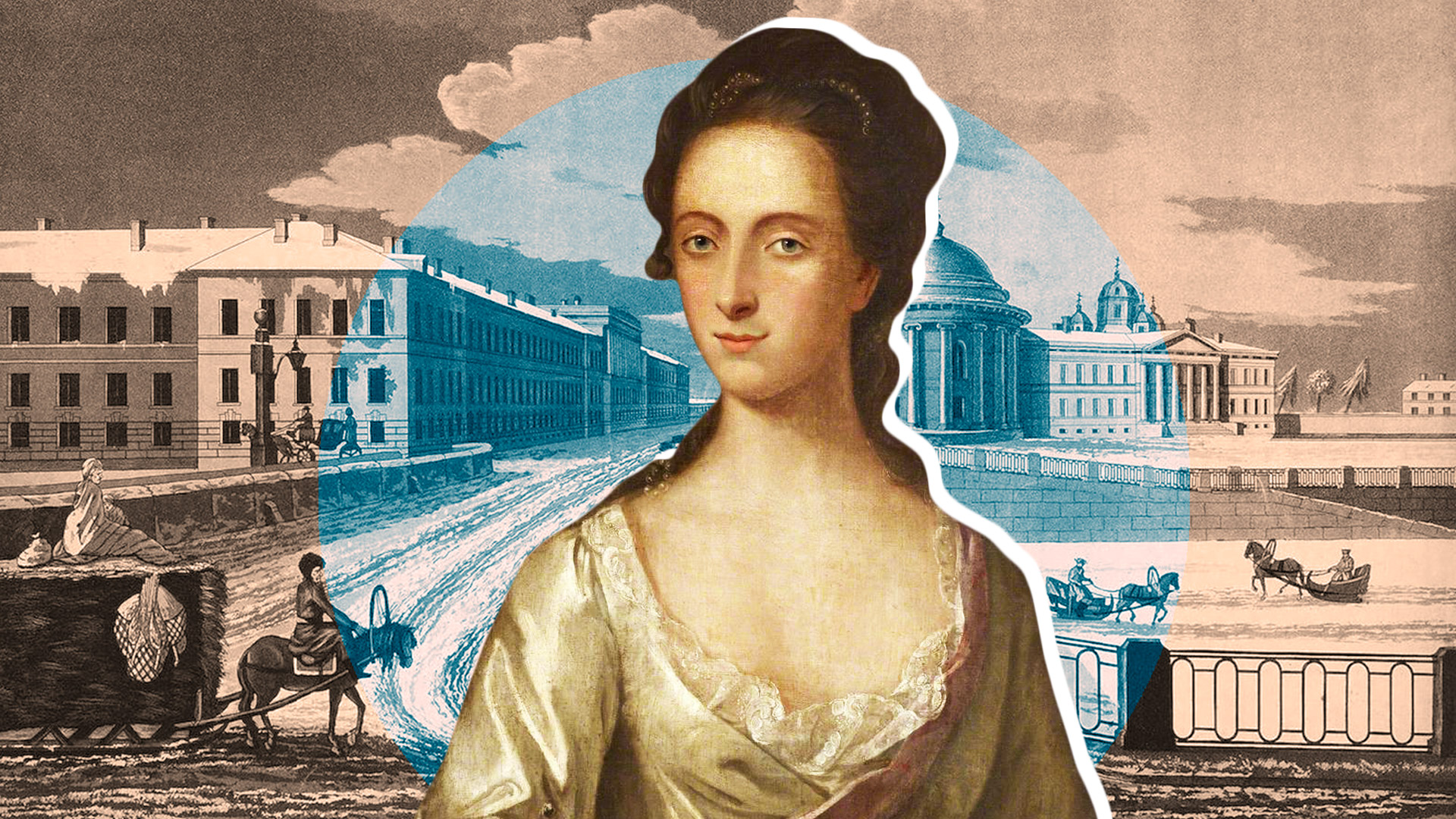

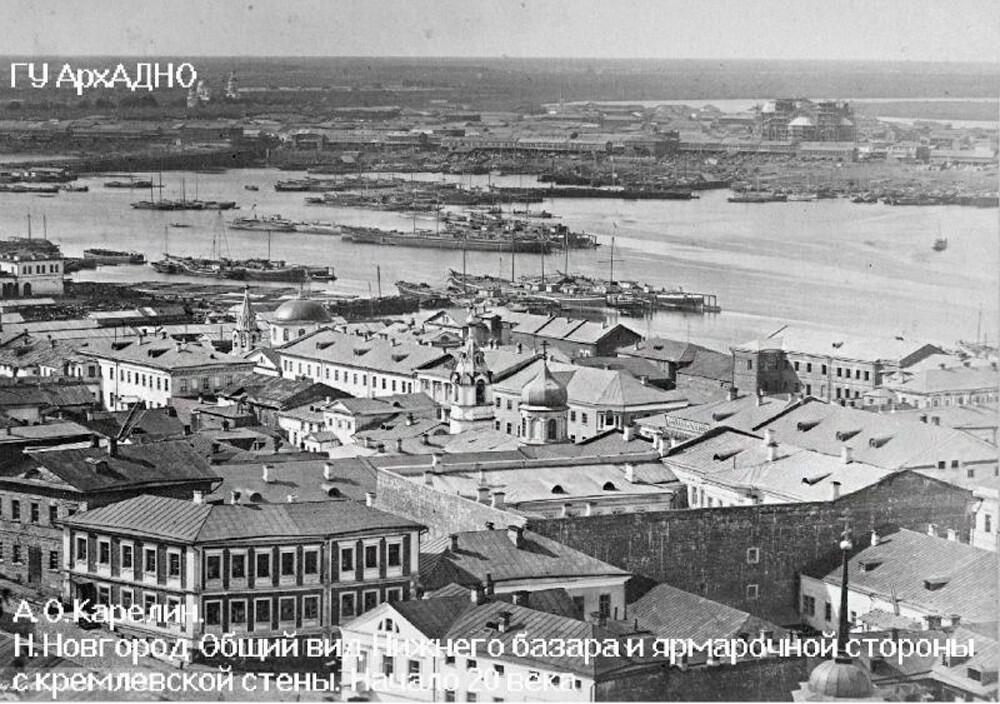

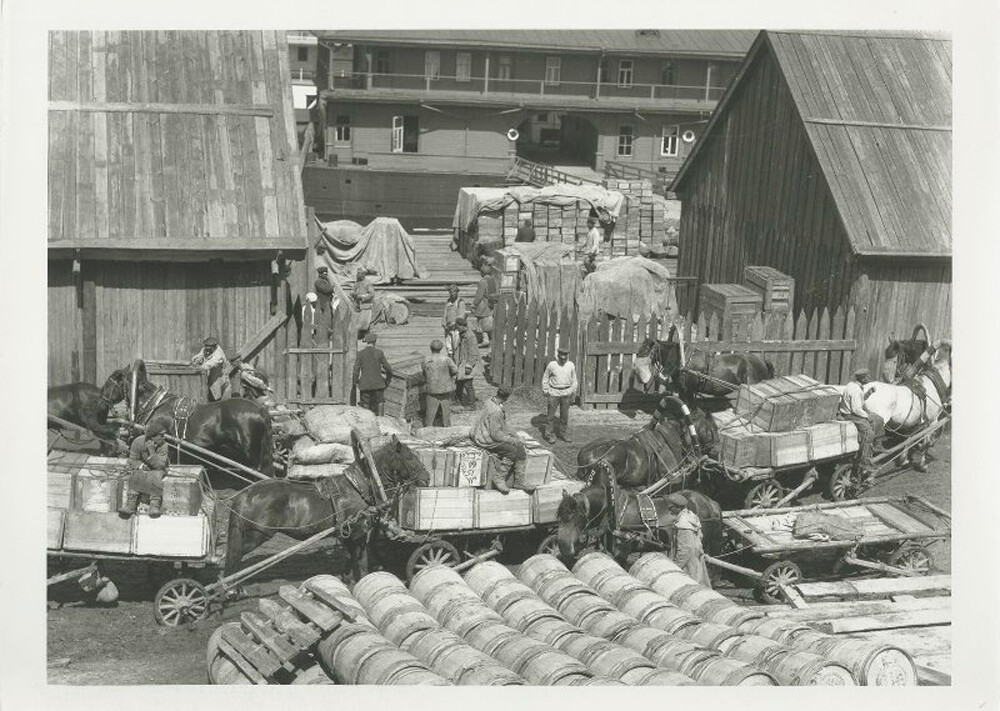

Nizhny Novgorod at the end of the 19th century

Nizhny Novgorod at the end of the 19th century

Initially, fairs were held not in the city itself, but by the walls of the Makaryev Monastery lower down the Volga. They were temporary affairs and lasted one or two days. In the 17th century, however, Tsar Aleksey Mikhaylovich established a five-day duty-free period for trade, thus attracting even more merchants. These often stayed for longer periods, paying tax to the treasury outside the period of exemption.

In the early 19th century, it became clear that the space near the monastery was not big enough to accommodate all comers and, furthermore, the makeshift rows of wooden shopping booths burned down at one point. By that time, the Nizhny Novgorod Fair had already become incredibly important, bringing an enormous amount of money to the state treasury.

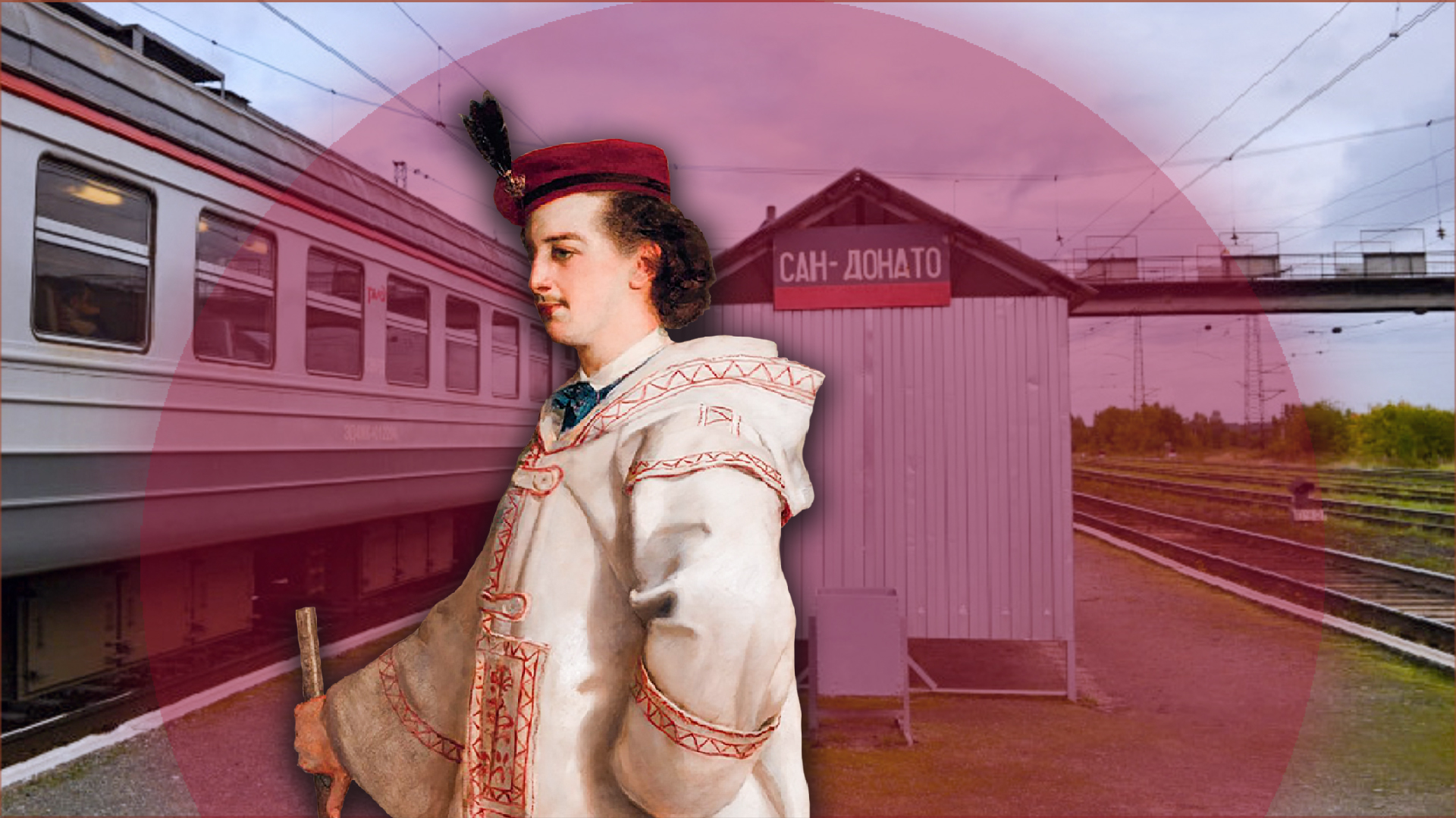

View of the fair at the end of the 19th century

View of the fair at the end of the 19th century

The fair was moved to Nizhny Novgorod proper - to the point of land where the Volga and Oka converge. Emperor Alexander I postponed repairs in his own palace to allocate six million rubles for the construction of a new building for the fair. And he didn’t lose out - merchants brought merchandise worth 24 million rubles to the first fair, which opened on the new site in 1817, with the figure increasing to 57 million rubles by 1846.

One of the buildings of the Gostiny Dvor (indoor market) in Nizhny Novgorod

One of the buildings of the Gostiny Dvor (indoor market) in Nizhny Novgorod

Contemporaries called the Nizhny Novgorod Fair the “trading court of Europe and Asia”. Foreigners sold their wares wholesale to local merchants and manufacturers and 90 percent of all goods from the East passed through the Nizhny Novgorod Fair, from where they were distributed throughout Russia. In turn, foreign merchants bought goods from Europeans and Russians.

What was bought and sold at the Nizhny Novgorod Fair?

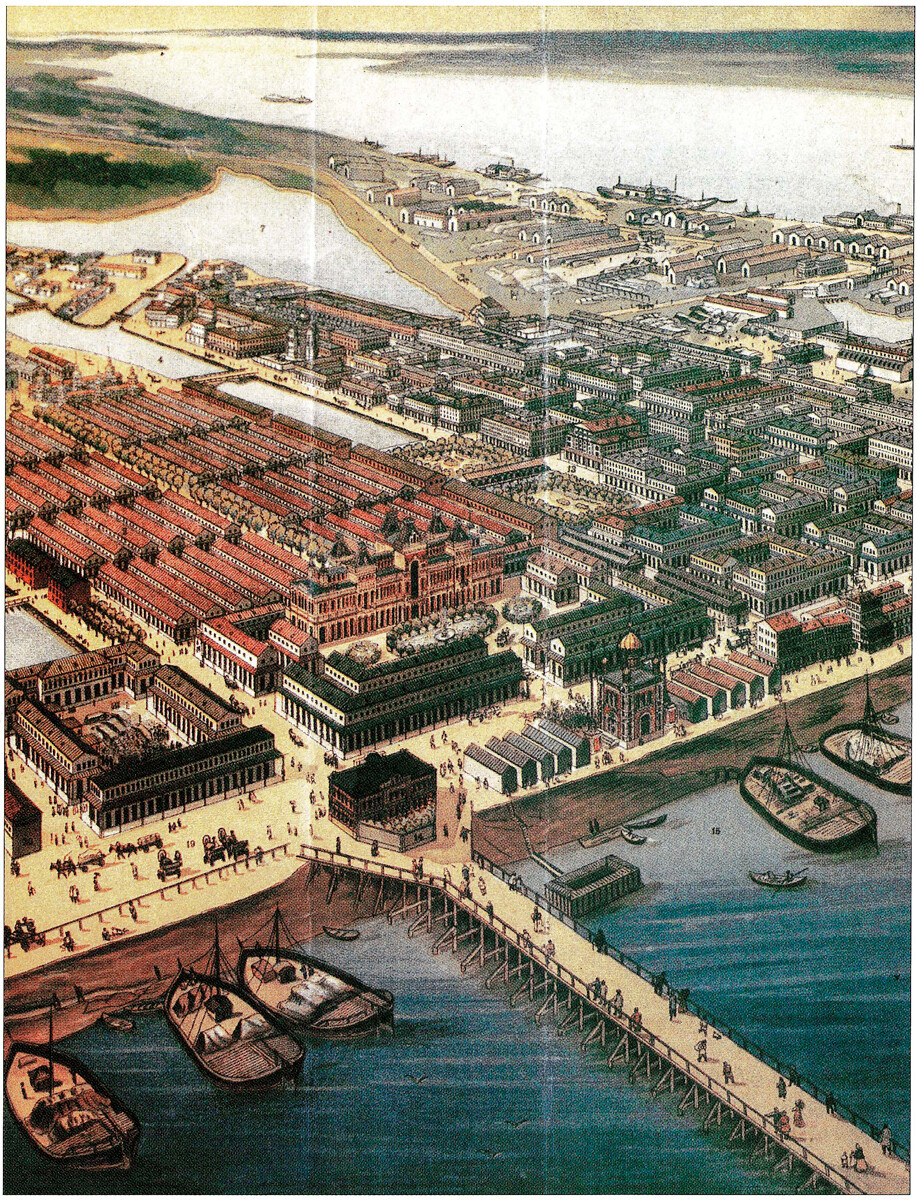

General view of the fair, chromolithograph, 1896

General view of the fair, chromolithograph, 1896

By the 1850s, up to 700 foreign merchants would attend the Nizhny Novgorod Fair. At the same time, the volume of trade with Asia in the middle of the 19th century exceeded turnover with Western Europe by one-and-a-half to three times.

One of the main items of trade was tea from China. In the 1880s, between 800 and 900 poods (a Russian unit of weight equal to about 16.38 kilograms) of tea worth 42 million rubles were brought to Russia every year. There were even separate Asian trading pavilions in the style of Chinese pagodas at the fair.

Chinese pavilions at the fair, late 19th century

Chinese pavilions at the fair, late 19th century

In return, the Chinese bought the furs and skins of all kinds of animals; from foxes, squirrels and muskrats to sheep and cow hide.

From Iran, handmade rugs, silks, cotton fabrics, as well as a wide range of dry foodstuffs - walnuts, pistachios, dried pitted and unpitted apricots, almonds, prunes, millet and rice - were brought to Russia. And the Persians themselves took back wool, metal and leather goods, porcelain, writing paper and many other things.

Pyotr Vereshchagin. Lower Bazaar in Nizhny Novgorod, 1860s

Pyotr Vereshchagin. Lower Bazaar in Nizhny Novgorod, 1860s

Russia also exported sugar, linen, hemp, cotton and leather goods, wool, wood, metals and much more to the East. The variety of merchandise was astounding. In the 1820s, Russian official Yegor Meyendorff gave a list of the goods purchased by Bukhara merchants: “The goods exported from Russia include cochineal [a red dye - ed.], cloves, sugar, tin, red and blue sandalwood, cloths, red Kungur, Kazan and Arzamas leather, wax, some honey, iron, copper, steel, gold thread, small mirrors, otter skin, pearls, Russian nankeen [cotton fabric - Russia Beyond], cast-iron cauldrons, needles, coral, plush, cotton headscarves, brocade, small glassware and a small quantity of Russian canvas…”

Fishing also became a very important article of trade. “Fishing for beluga, sturgeon, stellate sturgeon, catfish and some other fish species was almost completely monopolized by Russian merchants throughout the Southern Caspian,” according to historians A.A. Ivanova and A.V. Ivanov.

Fishing boat of the Murmansk fishery industry

Fishing boat of the Murmansk fishery industry

Over time, products from new developing industries, including metallurgy and textile manufacturing, were added to the exports. They included inexpensive chintz manufactured at the famous Shuya factories in Ivanovo Region. And, in the 1880s-1890s, trading in oil and oil products even began here.

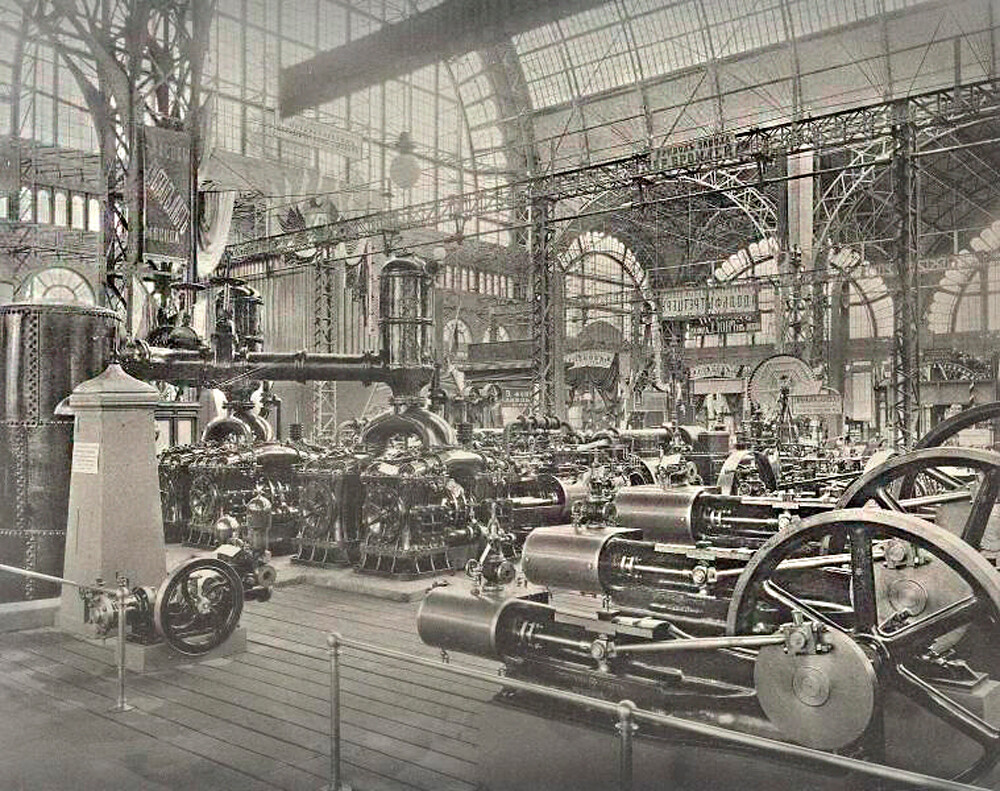

The machinery section at the fair in 1896

The machinery section at the fair in 1896

With the passage of time, bank branches were opened at the fair, the services of lawyers became available and exchange dealings were transacted. The fair was a very important event for major Russian merchants and manufacturers. But self-employed artisans and representatives of the arts and crafts industry also took a very active part. Spinning-wheels, wooden spoons, folk costumes, painted trays, crockery, lace - the work of the best artisans from all over Russia was represented. They, in turn, would spend the whole year preparing for the fair and would try to bring their best wares.

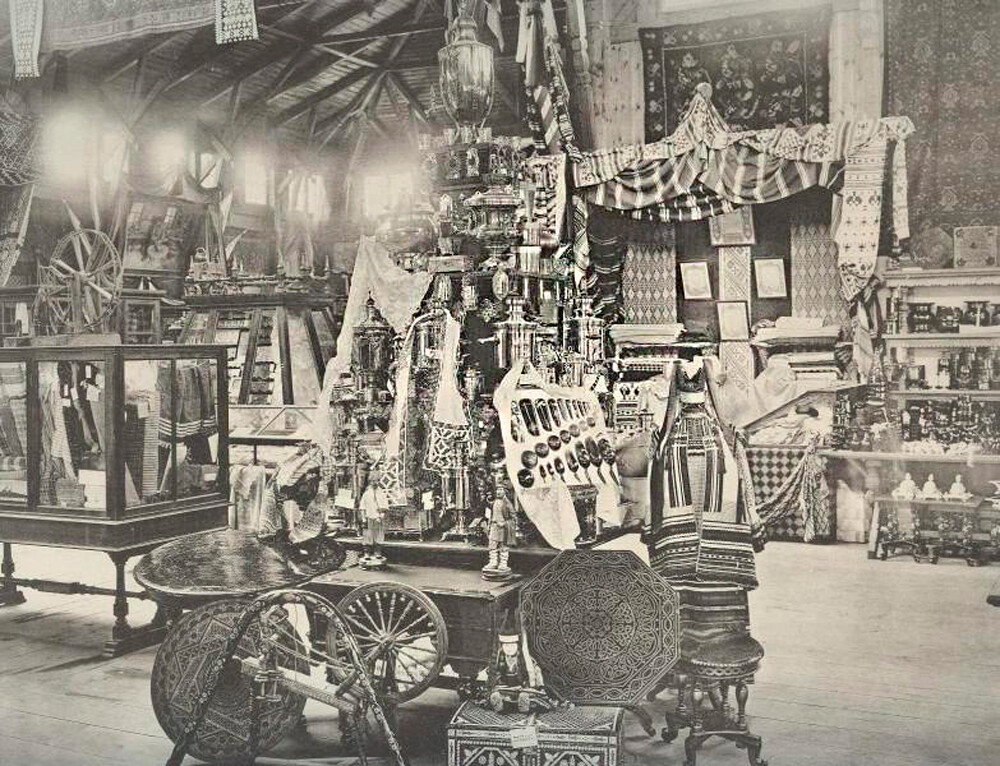

The handicrafts section in 1896

The handicrafts section in 1896

How the fair was organized

Jules Verne's ‘Michael Strogoff’ describes the Nizhny Novgorod Fair as follows: “This plain was now covered with booths symmetrically arranged in such a manner as to leave avenues broad enough to allow the crowd to pass without a crush. Each group of these booths of all sizes and shapes formed a separate quarter particularly dedicated to some special branch of commerce. There was the iron quarter, the furriers’ quarter, the woolen quarter, the wood merchants quarter, the weavers’ quarter, the dried fish quarter, etc… In the avenues and long alleys there was already a large assemblage of people… An extraordinary mixture of Europeans and Asiatics, talking, wrangling, haranguing and bargaining… On one of the open spaces between the quarters of this temporary city were numbers of mountebanks of every description; harlequins and acrobats deafening the visitors with the noise of their instruments and their vociferous cries… In the long avenues, the bear showmen accompanied their four-footed dancers, menageries resounded with the hoarse cries of animals…”

General view of the fair during spring high water on the River Oka, 1890

General view of the fair during spring high water on the River Oka, 1890

From the mid-19th century onwards, the official duration of the fair was a little over a month, but, in practice, trading continued from July to September. The fair was an occasion for general festivity in the city - more than 200,000 people would arrive in Nizhny Novgorod during the period of trading and there would be a circus and a theater and performing musicians. Electricity and water supply were brought to the site of the fair in the 1870s-1880s. The fair had a positive impact on the whole of the city - Nizhny Novgorod had convenient infrastructure facilities, and hotels and inns were extensively built. One of the first tram lines in Russia was inaugurated there in 1896.

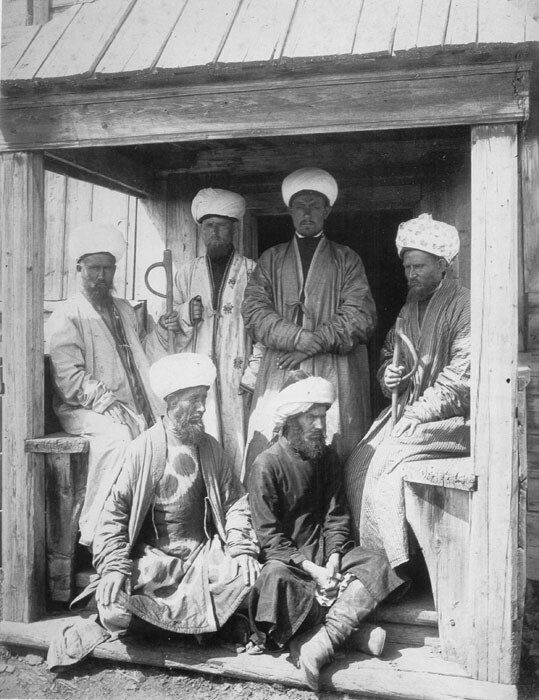

Eastern traders at the fair

Eastern traders at the fair

There were also two cathedrals at the site of the fair - the ‘Staroyarmarochny’ (“Old Fair”) Transfiguration Cathedral, which opened in 1822. The architect was Auguste de Montferrand (who later built St. Isaac’s Cathedral in St. Petersburg with a very similar colonnaded drum under the main dome).

The ‘Staroyarmarochny’ (“Old Fair”) Transfiguration Cathedral

The ‘Staroyarmarochny’ (“Old Fair”) Transfiguration Cathedral

In 1881, Emperor Alexander III himself, along with his spouse and son, the future Nicholas II, were present at the inauguration of the Alexander Nevsky ‘Novoyarmarochny’ (“New Fair”) Cathedral. Construction of a new main fair building, in the Russian style, was completed in the same year (the similar GUM department store on the Red Square appeared later). All three buildings survive to this day.

The fair’s principal building

The fair’s principal building

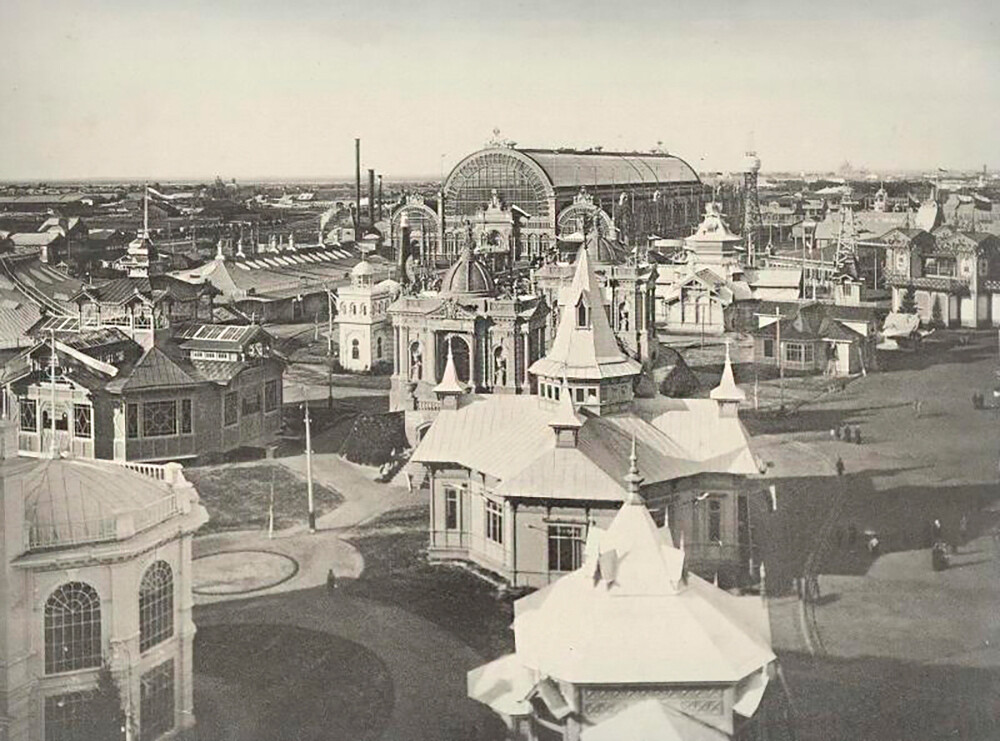

In 1896, the All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition was held in the grounds of the Nizhny Novgorod Fair - the biggest such exhibition in the history of the Russian Empire. More than 100 temporary pavilions were built for it. The first Russian motor car, as well as engineer Vladimir Shukhov’s steel lattice structures, were on display at the exhibition.

16th All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod, 1896

16th All-Russia Industrial and Art Exhibition in Nizhny Novgorod, 1896

After the 1917 Revolution, the fair continued to function for a time, but it was not as popular as before - and there was no longer any freedom of trade, the latter having been fully placed in the hands of the state. In 1929, the Bolsheviks finally closed down “this capitalist, socially hostile phenomenon”. Many of the fair’s buildings were demolished - or converted into residential housing.

One of the last Nizhny Novgorod fairs in the Soviet time, 1924

One of the last Nizhny Novgorod fairs in the Soviet time, 1924