Closed communities and fines for cursing: How Germans merchants lived in Russia

A German merchant living in medieval Russia could be fined for as little as publicly cursing – those were the rules imposed by the German Court at the trading station. This was not an excessive precaution: conflicts with locals were not uncommon and bringing arms on the territory of foreign courts was forbidden for the locals, among other things. But how did foreign merchants appear in old Russia, in the first place?

In the Middle Ages, the town of Veliky Novgorod (‘Novgorod the Great’), earlier known simply as Novgorod, was the main center of crafts and trade in Rus’. Foreign merchants wanting to do business in the East could get to it by water: The River Volkhov, along which the town stood, was linked to Lake Ladoga, from where, in turn, there was access to the Baltic Sea along the River Neva.

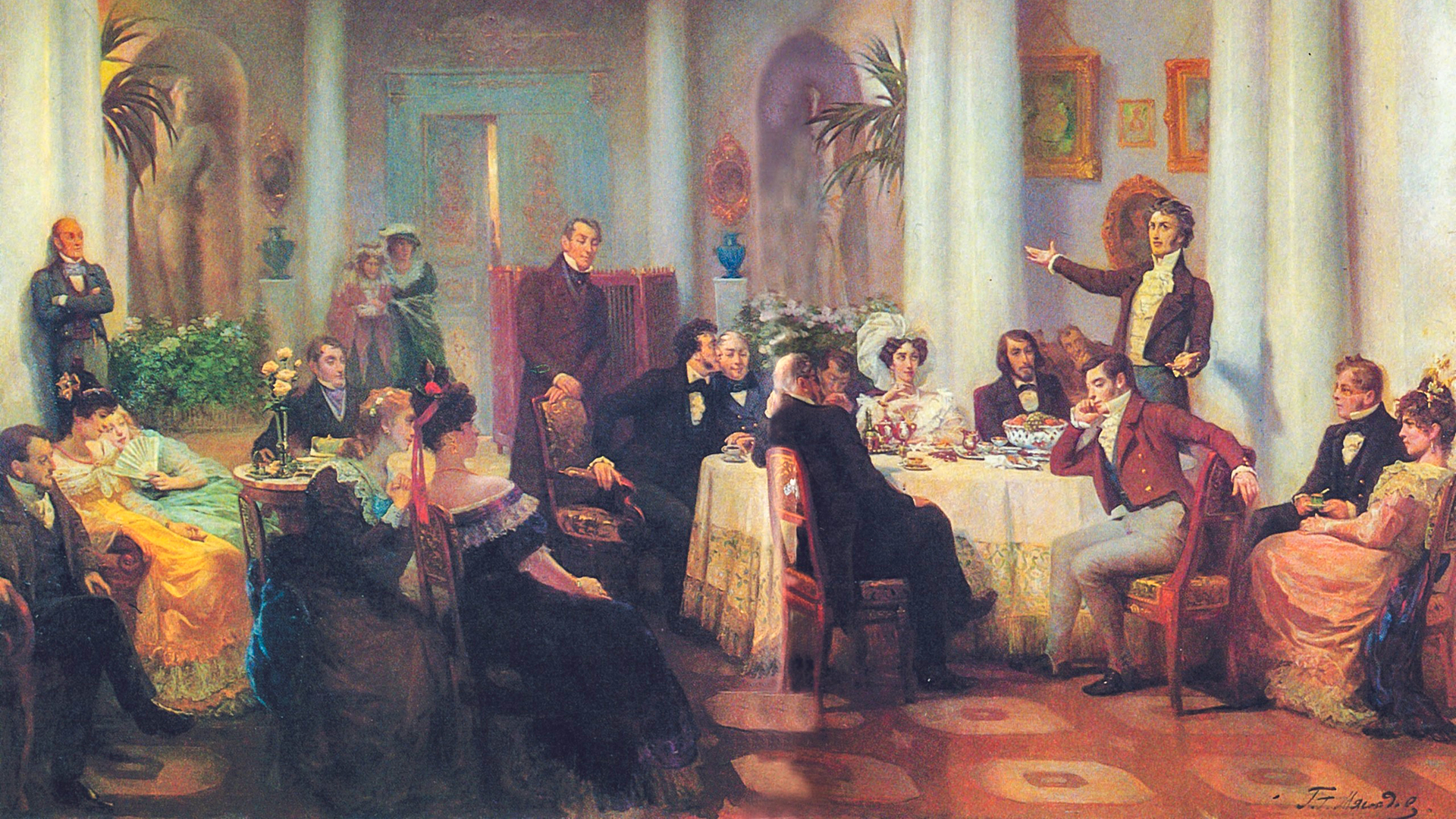

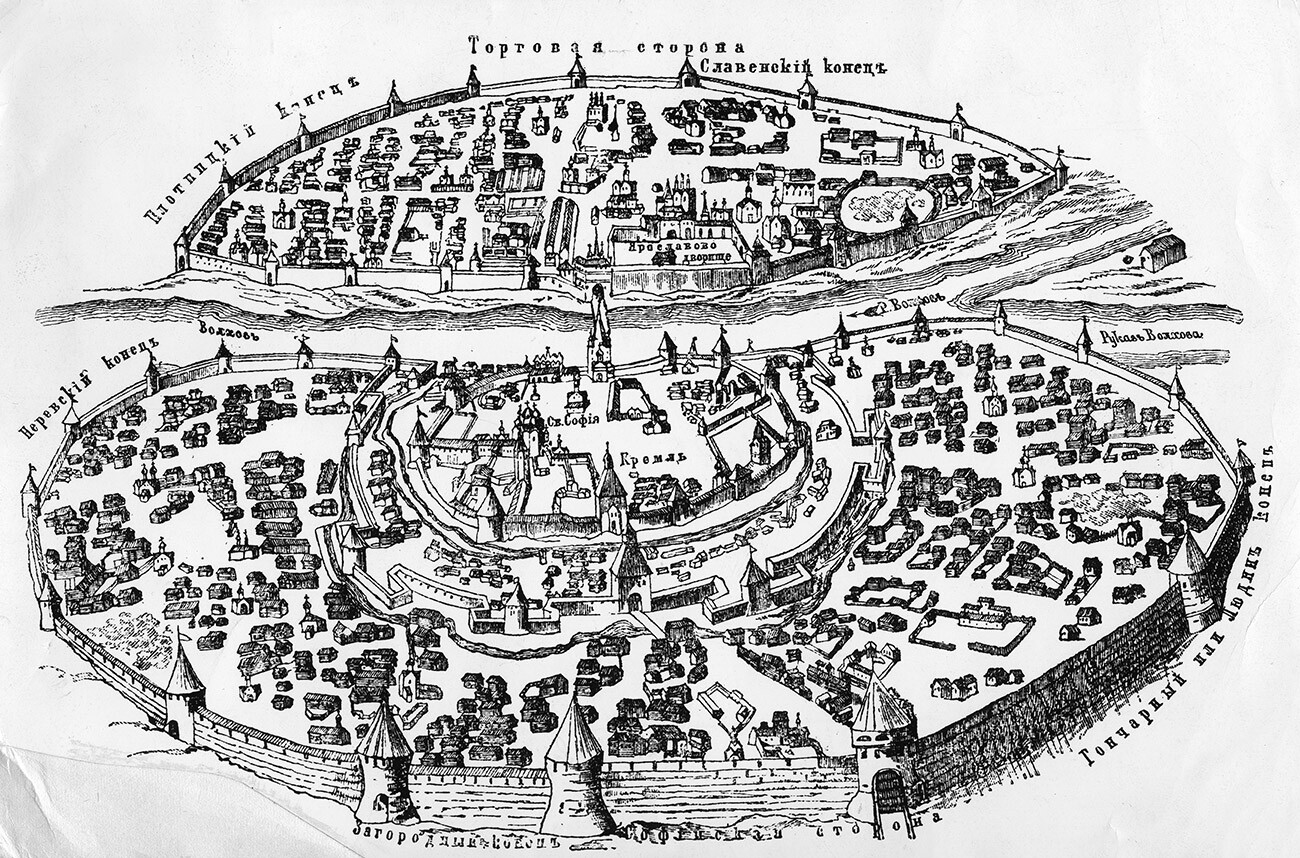

A 16th-century view of the Russian trade metropolis of Novgorod

A 16th-century view of the Russian trade metropolis of Novgorod

There were so many merchants that the first foreign trading stations - known as courts - were already established in Novgorod in the 12th century.

The first foreign trading posts

The first foreign trading station was established in the town in 1117 and named the Gothic Court, which represented merchants arriving from Gotland. The island, which frequently changed hands and at different times belonged to different states, occupied an important place in the Baltic trade: Its geographical location made it a kind of staging post where merchants stopped along their route.

Gotland and also Denmark and Sweden (to whom the island belongs today), dominated Novgorod’s foreign trade in the 12th century. There was also a Novgorodian trading post in the largest port on the island of Visby. The street where it stood still has “Russian” in the name - Ryska gränd.

Gotland Island, 1626

Gotland Island, 1626

In the second half of the century, another significant player emerged in the Baltic trade - the city of Lübeck. Realizing the significance of Gotland, the Germans were at pains to establish strong partnership relations with the island and, having set up operations there, they gained access to Novgorod too. In the Russian town, they could acquire furs, wax, honey and various Eastern goods for subsequent resale.

How the Germans became the principal trading partners

The trading cities on the shores of the Baltic and North seas gradually began to band together into confederations: Only by pooling their efforts could they ensure the safety of their expeditions and obtain privileges from their partners. One of these groups was the famous Hansa, or Hanseatic League. Novgorod was one of the chief trading partners of the new association.

Dutch map of the Hanseatic League cities and trade routes

Dutch map of the Hanseatic League cities and trade routes

The number of German merchants in Novgorod grew, and, with time, as Professor Elena Rybina, Doctor of Historical Sciences, notes, they squeezed out the Gotlanders and concentrated the Baltic trade in their own hands.

While they initially stayed in the Gothic Court during their business trips, by the end of the 12th century, in about year 1192, they set up their own trading post - the German Court - and, in the end, both courts ended up under the overall administration of the German merchants, becoming the trading station of the Hanseatic League. In the Winter of 1336/37, there were around 160 residents in the two Novgorod courts and, in 1439, the number was 200.

In Lübeck itself, as more and more associations of merchants with a regional focus were formed, the concept of ‘Nowgorodfahrer’ emerged to signify “guests of Novgorod” or “those who travel to Novgorod”.

How the German and Gothic courts were organized

The German Court in Novgorod

The German Court in Novgorod

Foreign merchants were allowed to enjoy freedom of worship and so, the courts had their own churches: The German Court had the Church of St. Peter, in honor of which the court itself was frequently called the ‘Court of St. Peter’ (St. Peterhof), while the Gothic Court had the Church of St. Olaf, which local people called the ‘Varangian Sanctuary’. This was the name, for instance, by which the latter featured in documents recording fires in Novgorod. Thus, in 1217, the chronicles report that “in the Varangian sanctuary, all the Varangian merchandise was burnt in untold quantities”. Both had cemeteries, which bore the names of the respective churches.

For the Germans, the churches performed not just a religious function but also a practical one: The court’s archive and particularly valuable items of merchandise were kept there. They had to be guarded because, despite clampdowns, the local population periodically tried to plunder them.

Coat of Arms of the Lübeck-Novgorod merchants

Coat of Arms of the Lübeck-Novgorod merchants

The church keys were issued to the priest, while the clergymen themselves were rotated: New ones arrived with the successive trade caravans that came to Novgorod twice a year - in winter and summer. They were, respectively, called the ‘winter guests’ (‘Winterfahrer’) and the ‘summer guests’ (‘Sommerfahrer’). Some of the caravans managed to make their way to the town by land and this method of travel gradually caught on - such travelers were described as ‘land guests’ (‘Landfahrer’), according to Philippe Dollinger, an expert on the history of the Hanseatic League.

The court would be headed by an elder called an ‘alderman’, elected by the merchants on their way to Novgorod; the Church of St. Peter also had its elder. According to the rules, those who turned down the office were required to be exhorted three times on behalf of the entire court and, if this was of no avail, they were fined. The same applied to the four assistants whom the aldermen appointed - they picked “four of the wisest men with whom they have had previous dealings”.

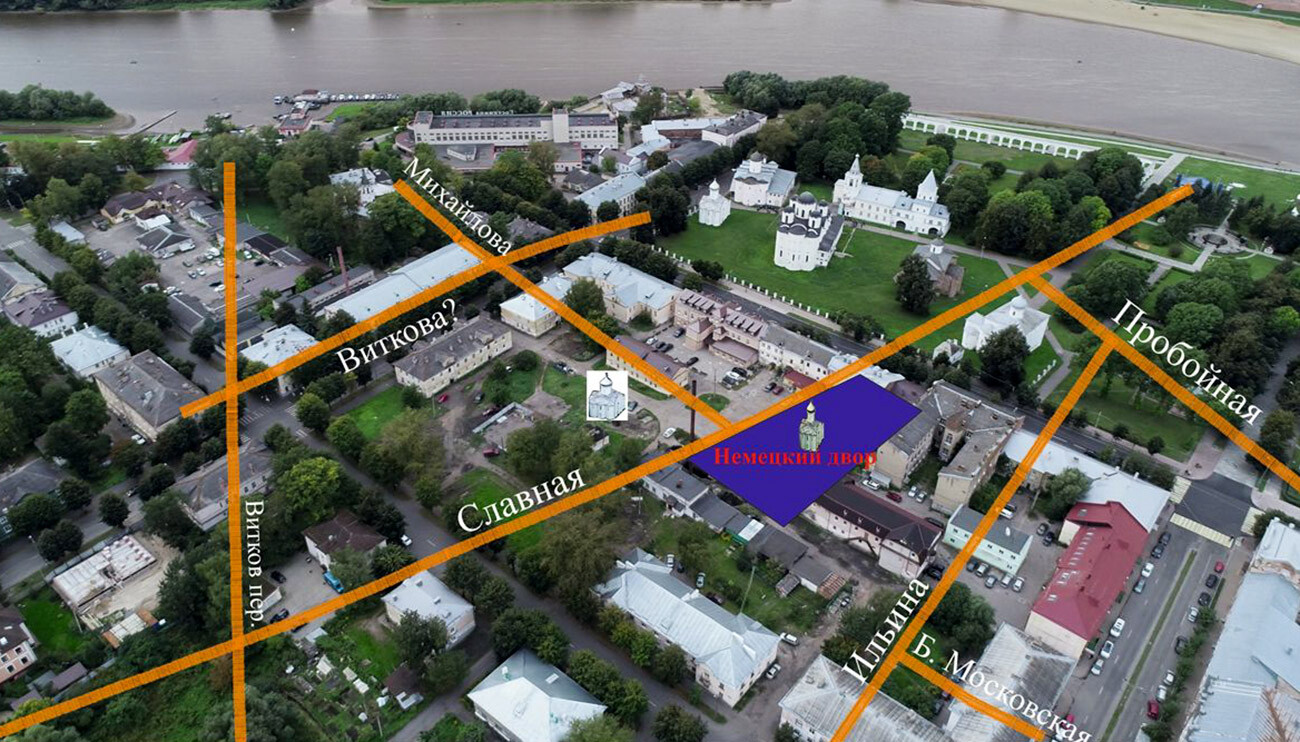

The exact location of the German Court was not known for ages. On the map the place is marked in dark blue.

The exact location of the German Court was not known for ages. On the map the place is marked in dark blue.

While burdened with additional obligations, the aldermen also enjoyed certain privileges - for example, they were exempted from the obligation of guarding the court and church and they were given a choice of living quarters for themselves and their companions, for which they paid no rent, while everyone else was required to draw lots and pay for their accommodation. Subsequently, the power to elect the aldermen passed to representatives of the towns and, in the 16th century, members of specially elected panels carried out this function.

The regulations that governed the Germans’ lives

The German Court conducted its affairs according to a special statute: It was called the ‘Schra’ and listed the principal laws and specified the fines for breaking them. Throughout the existence of the courts, this statute was continually updated and, in addition, certain guidelines regulating life in the courts were also stipulated in trade agreements between the towns. For instance, one of them set boundaries on the territory of the courts, prohibiting the repositioning of the palisades around them and the erection of new buildings and also prohibited the dumping of trash.

In early 2021, Russian archaeologists found traces of the German Court in Novgorod.

In early 2021, Russian archaeologists found traces of the German Court in Novgorod.

Fines were imposed for the most diverse misdemeanors: from failing to attend assemblies to uttering insults (“calling people knave or son of a whore or liar or suchlike words”). The third edition of the ‘Schra’ even had a chapter headed ‘On the Rights of Workers’, which laid down protections for servants hired by the merchants. For instance, they could not dismiss them because of illness or before their return home unless for a compelling reason.

Conflicts used to flare up occasionally between the people of Novgorod and the foreigners, resulting, for instance, in the local people being prohibited, under penalty of criminal prosecution, from entering the territory of the German and Gothic courts carrying arms. This regulation was sometimes breached, however, as in the case of major fires in the town.

Archaeological findings, presumably from the German Court

Archaeological findings, presumably from the German Court

One broke out in 1299, having originated in the German Court. “And the fire leapt from the German Court to Nerevsky End… And the devastation it caused was great; and so it was that God and the good people on earth stopped it; and wicked people devoted themselves to plundering: and what was in the churches, they took it all as plunder,” is how one of the Novgorod chronicles described the incident.

The Germans even gradually formed their own judicial bodies, in which the most senior role was allotted to the alderman, whose powers, however, were limited to ensure the avoidance of malpractice. Collecting all sorts of fines, the Germans managed to set up a communal treasury, the contents of which, after the deduction of expenses, was sent by them to Gotland and Lübeck.

Appolinary Vasnetsov. Novgorod Marketplace, 17th century

Appolinary Vasnetsov. Novgorod Marketplace, 17th century

In the 15th century, the power of the Hanseatic League began to fade along with the Baltic trade. After the Moscow authorities established control over Novgorod, the German Court was closed down, only to resume operations 20 years later. But, the new court was never to attain the significance its predecessor had enjoyed and it repeatedly found itself on the brink of disappearing.