How the Brits turned over the Cossacks who had fought for Hitler to the Soviet Union

In the Spring of 1945, no one had any doubts that the war in Europe would soon be over. Now, the only task of the Germans was to hold off the “wild Russians” as long as possible, in order to surrender to the British and American troops approaching from the West.

Among those who, in no way, wanted to end up in the hands of the Red Army were the Cossacks, who had fought for Hitler. The natives of the Southern Russian steppes had no doubt that they would have to be held responsible to the Soviets for cooperating with the enemy.

Southwestern Austria was the place where the retreating Cossack formations gathered. Over 45,000 fighters and their families (according to other reports, about 60,000) managed to get there in early May and capitulated to the British, who had occupied the region.

They were certain that they had avoided the threat - but, as it turned out, it was in vain.

Together with Hitler

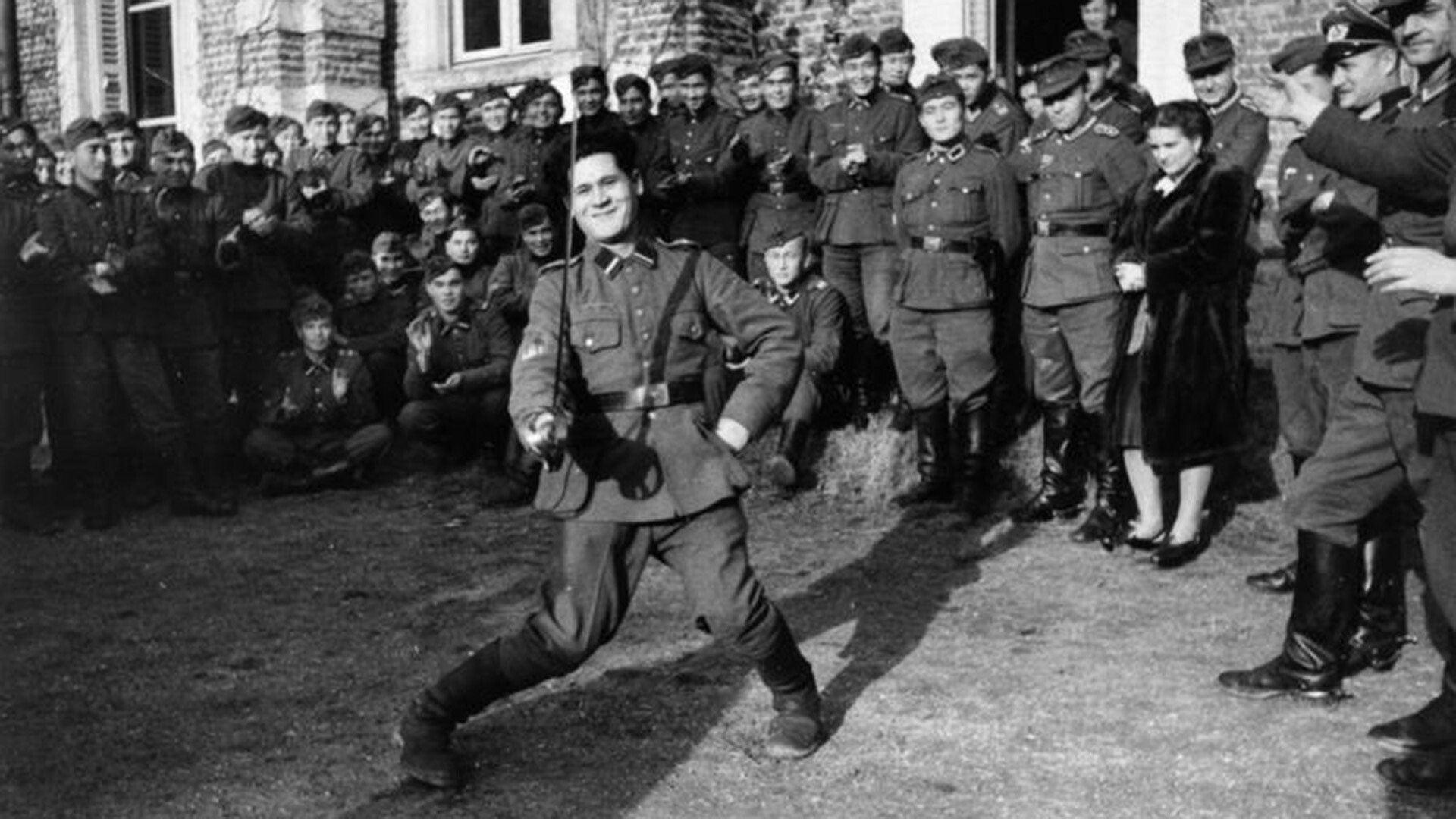

While the vast majority of the Don, Kuban and Terek Cossacks fought against the Germans in the Red Army, some of them joined the Nazis.

In addition to Cossack Soviet citizens who were dissatisfied with the Soviet government, emigrant Cossacks also fought as part of the Wehrmacht and the SS. Having left their homeland after the victory of the Bolsheviks in the Civil War, they returned there with their sons to take revenge on their old offenders.

Thus, on the first day of the German invasion, Ataman Pyotr Krasnov, who had settled in Germany, made a statement: “I’m asking you to convey to all the Cossacks that this war is not against Russia, but against the Communists, the Jews, and their henchmen who trade in Russian blood. May God help German arms and Hitler!”

Ataman Pyotr Krasnov.

Ataman Pyotr Krasnov.

The Nazis, who proclaimed the Cossacks to be descendants of the German Gothic tribes, supported the creation of Cossack formations. The most significant among them were the military organization Cossack Camp and the 15th SS Cossack cavalry corps.

The Cossacks demonstrated themselves as loyal and efficient fighters. They carried out garrison service in the occupied territories of the Soviet Union, took part in punitive actions against guerrillas and fought against regular units of the Red Army. Among their “deeds” was participation in the brutal suppression of the Warsaw Uprising in August-October 1944.

The Germans also used Cossacks in their counter-guerrilla struggle in Yugoslavia and Italy. It was from the Apennine Peninsula at the end of the war that they broke through to Austria, where they surrendered to the Brits and were placed in camps near Lienz and Judenburg.

Repatriation

Under the agreements reached at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, the Western allies were to pass over to Moscow all Soviet citizens who had fallen into their hands, both prisoners of the camps and collaborators.

The British operation on the extradition of Cossacks to the Soviet side began with the “decapitation” of Cossack formations on May 28. About two thousand officers were taken out of the dispositions to attend a “conference”, after which they were immediately handed over to the Soviet state security bodies.

The Brits began to move the bulk of the prisoners of war on the morning of June 1. Because the latter resisted, it all quickly turned into a bloodshed. “The British soldiers attacked the Cossacks and, stunning them on their heads with clubs or gun butts, picked up the unconscious and threw them into trucks, taking them to the station and there, they locked them in freight cars,” recalled one of the Terek Cossacks, an eyewitness of the events at Camp Peggetz.

'The Betrayal of the Cossacks at Lienz, 1945'.

'The Betrayal of the Cossacks at Lienz, 1945'.

The detainees tried to escape at every opportunity, breaking through the lines of soldiers, jumping out of trucks and train cars. Those who failed to do so, hurriedly threw away their personal documents, photographs and decorations. Also, there were those who preferred suicide to returning to the Soviet Union.

By mid-June, the extradition of Cossacks to the Soviets was completed. According to various estimates, several hundred to a thousand people died along the way.

Trial

Great Britain did not limit itself to handing over only Soviet citizens who had collaborated with the enemy to its Eastern ally. Along with the collaborators, emigrant Cossacks, who had never had a Soviet citizenship and were not subject to extradition, were also sent to the USSR.

Among them, in particular, were major figures from the Cossack movement: Ataman Pyotr Krasnov, who took part in the creation of the Cossack Camp, his great nephew, Major General Semyon Krasnov; Andrei Shkuro, the head of the Cossack Army Reserve and General Helmut von Pannwitz, commander of the 15th SS Cossack Corps.

Cossack leaders at the Moscow trial.

Cossack leaders at the Moscow trial.

As a German citizen, the latter could have avoided being sent to the Soviet Union, but decided to share the fate of the others, stating: “I have shared happy times with my Cossacks, I will remain with them in misfortune as well.” In common with his high-ranking associates, he was convicted of conducting “active espionage and sabotage, as well as terrorist activities against the USSR” and was hanged on January 16, 1947.

Ordinary Cossacks ended up in camps, where some of them soon died. Women and children were the first to be released; in 1955, under the Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, “On the Amnesty of Soviet citizens who collaborated with the occupation authorities during the Great Patriotic War”, their husbands and fathers were also granted amnesty.