How did Russian prison music emerge?

The Russian people have always sung in chorus – since ancient times. They sang even when they were shackled and led to the stockade. In 1860, in Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel Notes from the Dead House, the author first introduced the reading public to the concept of the Russian prison song.

"There was singing in all the wards. But drunkenness was passing into stupefaction and the singing was on the verge of tears. Many of the prisoners walked to and fro with their balalaikas, their sheepskins over their shoulders, twanging the strings with a jaunty air. In the special division they even got up a chorus of eight voices. They sang capitally to the accompaniment of balalaikas and guitars. Few of the songs were genuine peasant songs. For the most part they sang what are called in Russian ‘prison songs’, all well-known ones." This is how Dostoevsky described the songs of criminals in Siberia in the second half of the 19th century.

'Convicts at a halt,' 1861, by Valeriy Yakobi

'Convicts at a halt,' 1861, by Valeriy Yakobi

In his 1871 book Siberia and Exile, ethnographer Sergei Maximov pointed out that there were old and new prisoner songs. The first ones originated from robber songs composed by "dashing people", wandering Cossacks, who participated in the conquest of the Volga and Siberia.

When robbers were eventually caught by the authorities they often ended up in Siberian prisons (like the Omsk prison camp where Dostoevsky was imprisoned), and that’s how robber folklore took root and flourished in the prison world. Many songs in the second half of the 19th century, Maksimov points out, "were not received by us from the first hands (from prisons), but perhaps from the tenth ones (from old-timers' villages, from free Siberian people)" who had previously had some contact with the prisoners.

Lenin’s favorite song

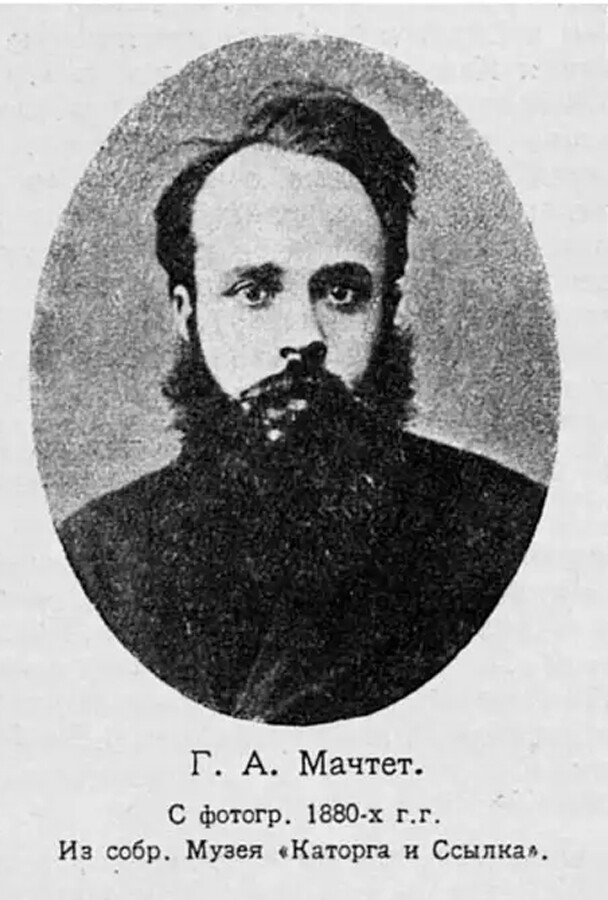

Grogoriy Matchet, author of 'Tortured by a Heavy Captivity'

Grogoriy Matchet, author of 'Tortured by a Heavy Captivity'

By the end of the 19th century, "arrestant" songs were popular not only among criminals but also in revolutionary circles. As Maxim Kravchinsky points out in The History of Russian Chanson, even Lenin had his favorite "arrestant song", which was called "Tortured by a Heavy Captivity" (Замучен тяжелой неволей) and which was dedicated to the memory of Samara student Pavel Chernyshev who was arrested for "going to the people" — conducting revolutionary propaganda among the peasants and workers by working alongside them. This method was commonly used by early Russian social democrats in the 1860s and 70s.

After spending two years under arrest, Chernyshev had contracted tuberculosis and succumbed to the disease. His funeral in St. Petersburg in 1876 turned into a huge anti-government demonstration.

Tortured by a heavy captivity,

You died an honorable death.

In the battle for the good of the people

You laid your head down like an honest man

This song was written by the populist revolutionary Grigory Matchet in the year of Chernyshev's death, and it became widely popular among Russian revolutionaries. With high probability we can conclude that this song had a special meaning for Lenin because Chernyshev was a legend in the revolutionary underground of Samara, the city where Lenin spent many years and was formed as a revolutionary.

Maxim Gorky and the prison song

A still from the production of 'The Lower Depths' by Maxim Gorky at the Moscow Art Theater

A still from the production of 'The Lower Depths' by Maxim Gorky at the Moscow Art Theater

In 1902, the very concept of the prison song was first heard on the big stage, when on December 18, Maxim Gorky's play The Lower Depths premiered at the Moscow Art Theater. This play is about the life of those who inhabit the bottom of society, and it takes place in a night lodging house. There, they sing the song "The Sun rises and sets", which one of the most famous prison songs at the time. The success of the play was incredible, and the image of the jaybird, "a shredded one", as they said at the time, was fixed on the stages of restaurants, cabarets – everywhere where such popular songs were sung.

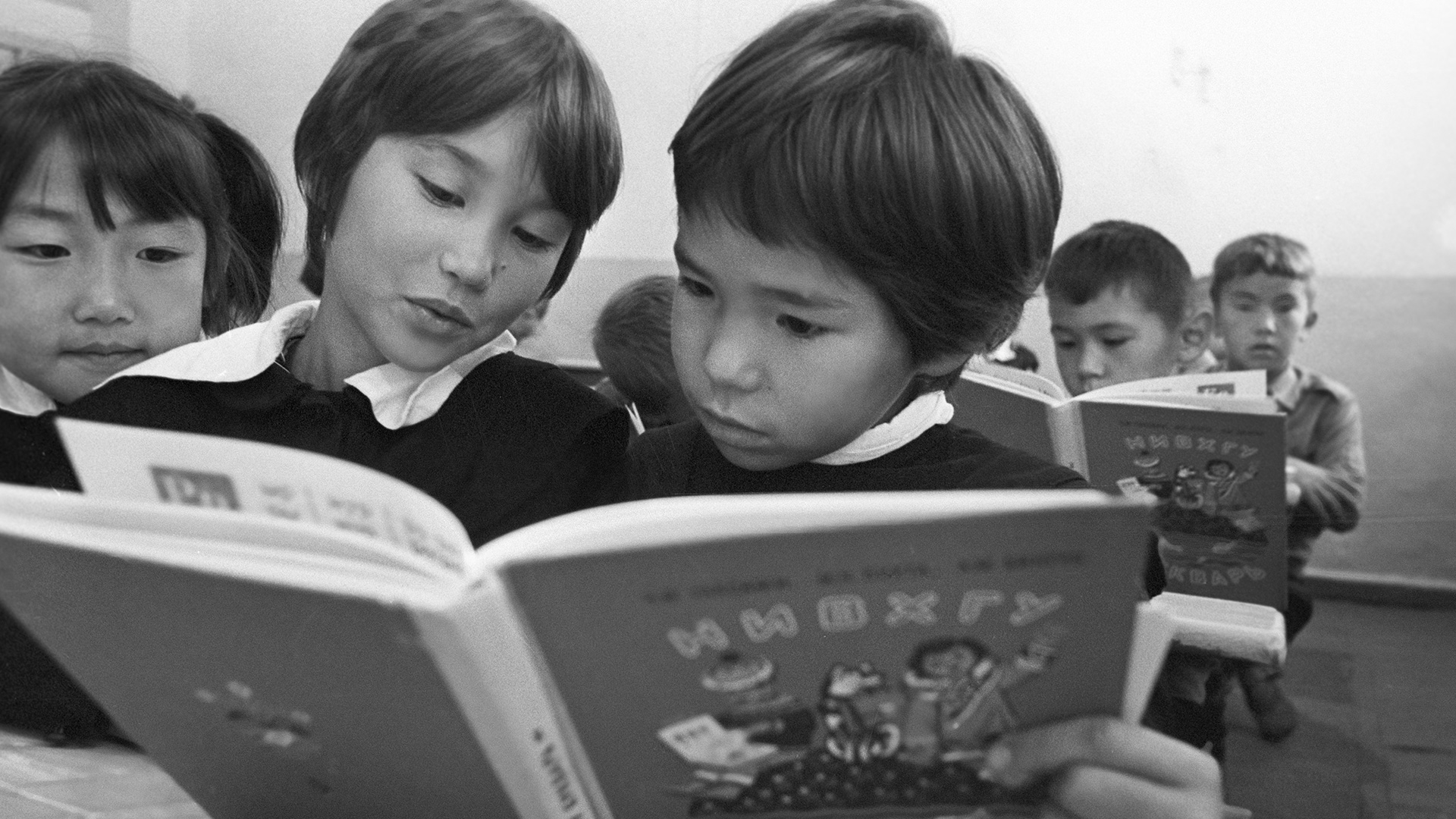

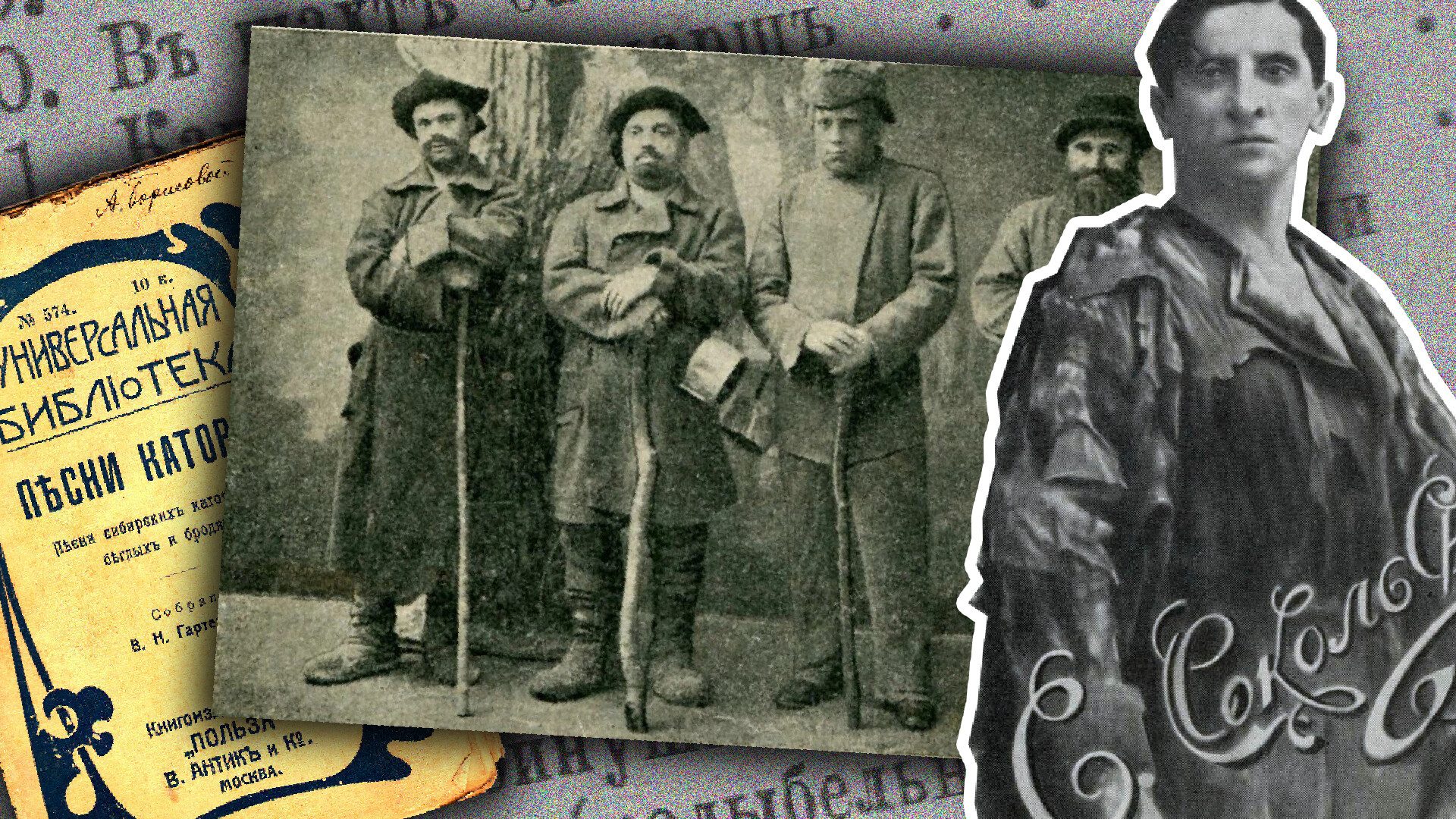

A quartet of ‘Siberian vagabonds,’ circa 1912-1913

A quartet of ‘Siberian vagabonds,’ circa 1912-1913

In 1903, the "king of reporters" Vlas Doroshevich published his famous work about the Sakhalin penal colony, which was given a separate chapter in "Songs of the Penal Colony". The words go like this: "The convicts sang the song of Siberian vagabonds ‘The Merciful Ones’... But what kind of singing it was! It was as if someone was being buried, as if funeral singing was coming from the shackle prison. It was as if this prison, looking into the gloom through its latticed windows, was singing a lament to the people buried alive in it".

Then came the Revolution of 1905, and amid the easing of state restrictions that followed, the "arrestant" songs were allowed to be published. In 1908, the musician and ethnographer Wilhelm Harteveld published a book "Songs of the Penal Colonies — Songs of Siberian convicts, fugitives and vagabonds". This marked the moment when the convict songs truly reached the Russian people – now they could be sung by anyone who could read sheet music. Harteveld himself performed these songs, and recordings were issued on gramophone records.

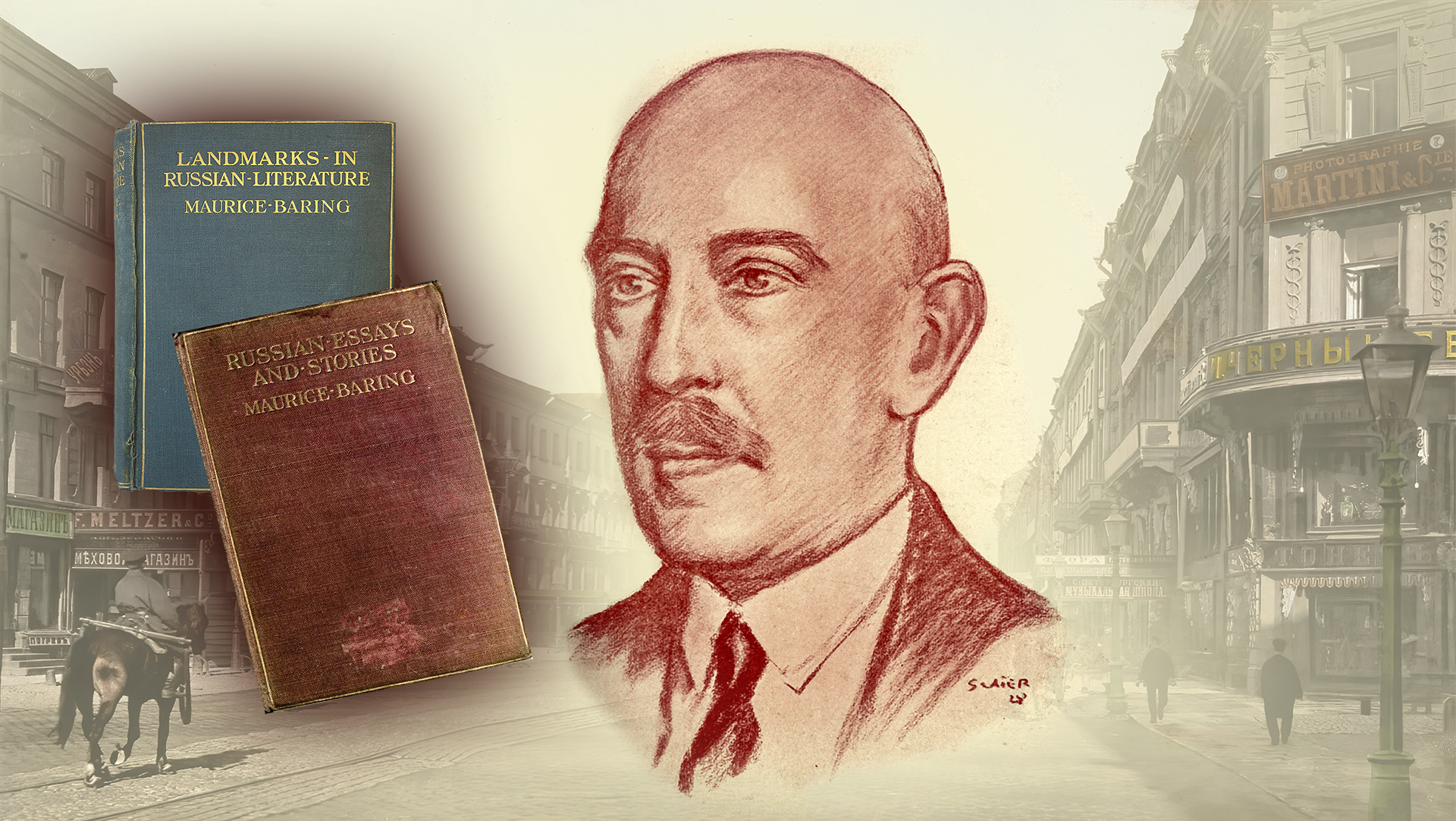

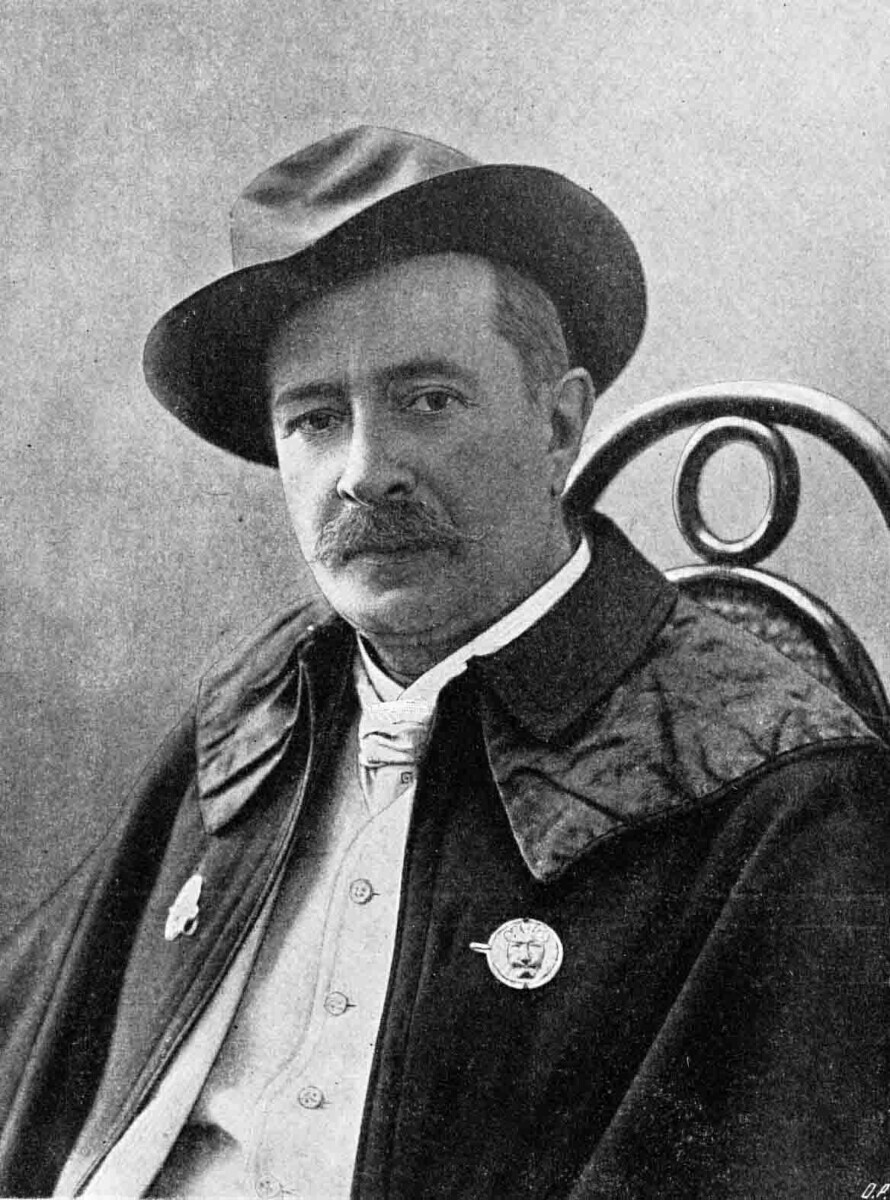

Wilhelm Harteveld (1859-1927)

Wilhelm Harteveld (1859-1927)

In 1909, Harteveld was performing prisoner songs in the hall of the Moscow Noble Assembly, but an attempt in 1910 to make an open performance on the stage of the Hermitage Theater failed – the concert was personally banned by the Moscow mayor.

No one, however, could prevent major stars from performing these prison songs in their programs. And so, "The Sun rises and sets" was sung by Fyodor Chaliapin. Famous singers Sergei Sokolsky (Ershov) and Stanislav Sarmatov performed in the image of a jaybird (‘bosyak,’ a barefoot in Russian), and duets, quartets, and choirs of "genuine Siberian vagabonds" were created all over Russia. Writer Nikolai Nosov recalled: "The songs performed by the quartet of ‘Siberian vagabonds’ were very consonant with the era. They reflected the public mood of the pre-revolutionary years."

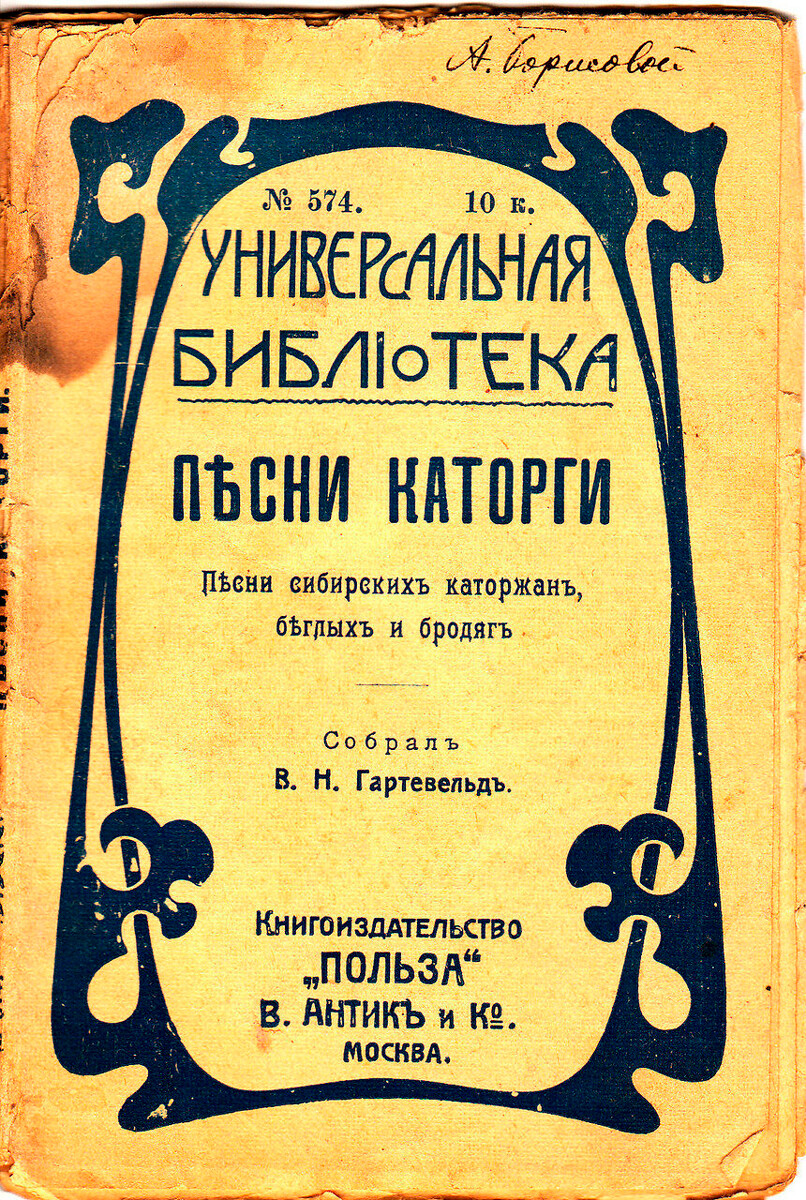

'Songs of the stockade,' 1908, collected by Wilhelm Harteveld

'Songs of the stockade,' 1908, collected by Wilhelm Harteveld

As Maxim Kravchinsky wrote, from 1906 to 1914, more than a hundred different collections of robber, beggar, convict, vagrant and prisoner songs were published in Moscow and St. Petersburg alone.

Famous singer Sergey Sokolsky in the image of 'a shredded one'

Famous singer Sergey Sokolsky in the image of 'a shredded one'

In the meantime, a new criminal folklore was born in the Russian provinces that formed the so-called Pale of Settlement (the territories where Jews were allowed to live permanently. Today, this is modern-day Belarus and Moldova, much of Lithuania, Ukraine and east-central Poland. Limited in rights and economic opportunities, many Jews joined criminal circles. Odessa especially had a plethora of Jewish criminal groups. Jews developed their own music – known as ‘klezmer’ – and brought it with them into the criminal world, which, when mixed with Russian prisoner songs, gave birth to a new genre – the "blatnaya" song, which flourished in the Soviet Union.