Did Ivan the Terrible really poke out the eyes of the architects of St. Basil’s?

Up until the 1950s historians believed that the Cathedral of the Intercession of the Most Holy Theotokos on the Moat (Pokrovsky Cathedral, better known as St. Basil’s Cathedral) was designed by two architects who are known to history only as Postnik (or Posnik in some documents) and Barma. It has since turned out, however, that this premise is false and most likely it was based on a scribe’s mistake.

Why the story about two architects?

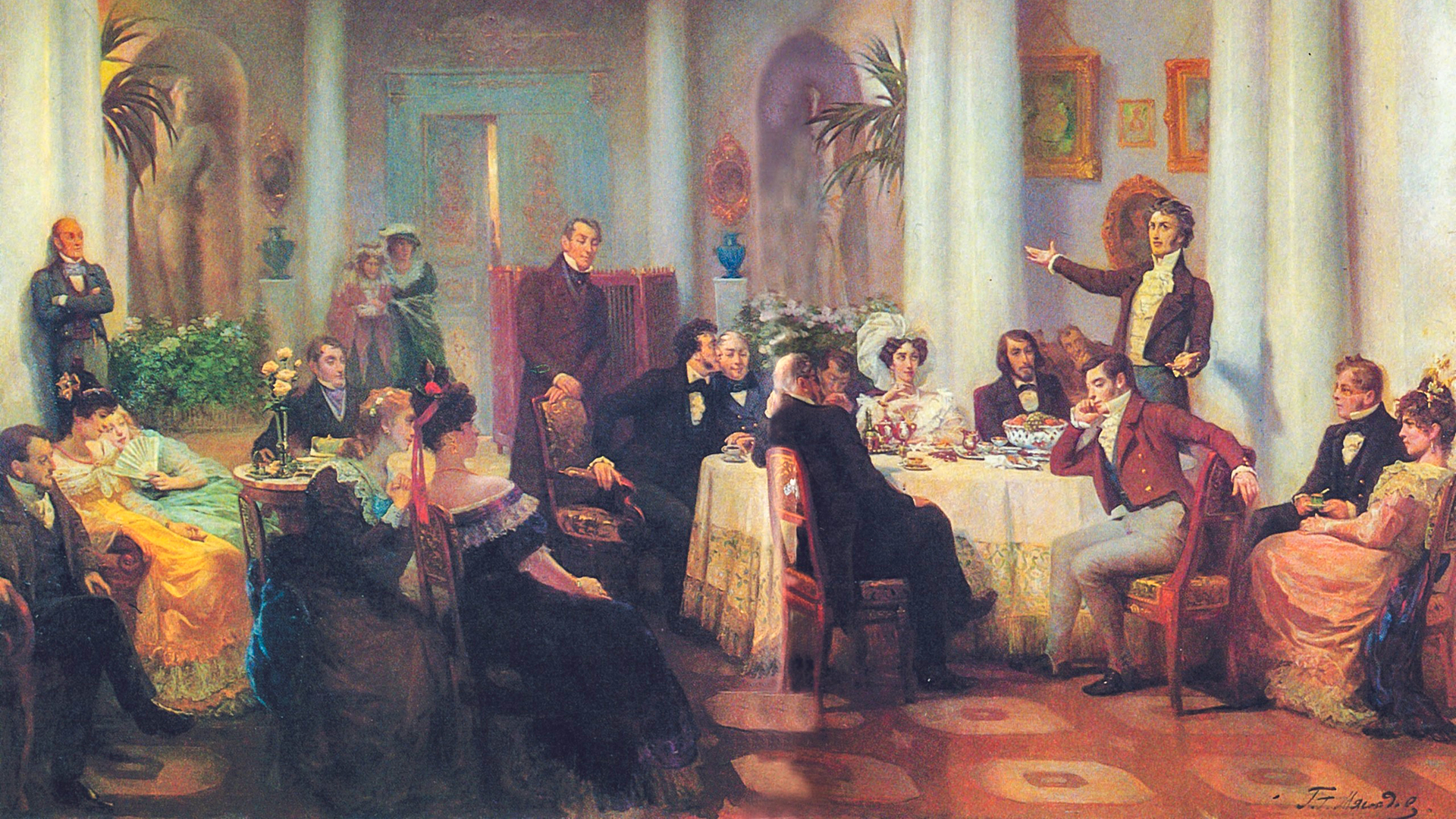

The construction of the Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed. A picture from the Illustrated Chronicle, 16th century.

The construction of the Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed. A picture from the Illustrated Chronicle, 16th century.

In 1957, in the magazine Soviet Archaeology, Nikolai Kalinin, a historian from Kazan, cited a document that became the basis of this widespread myth. In a handwritten collection of tales, written at the end of the 17th and the beginning of the 18th centuries, there is a “Tale of the transfer of the miraculous image of Saint Nicholas”. This icon was the gift of the Tsar to the newly-built cathedral in 1556. This text – by whom and when it was written is not known – has the following lines: “[The Tsar] ordered… a stone church near the Frolovskie (currently Spassky - RB) gates [of the Kremlin] over the moat. And then God gave him two Russian master craftsmen, known as Postnik and Barma, and they were wise and suitable for such a miraculous deed.”

Nikolai Kalinin noted that “known as Postnik and Barma” indicates that those were their nicknames. In Old Russian this meant that these were not their given names but rather aliases. This could indicate that there was an error in the records. Postnik is definitely a name, since it is mentioned many times in other documents, and he definitely was an architect.

Are Postnik Yakovlev and Barma the same person?

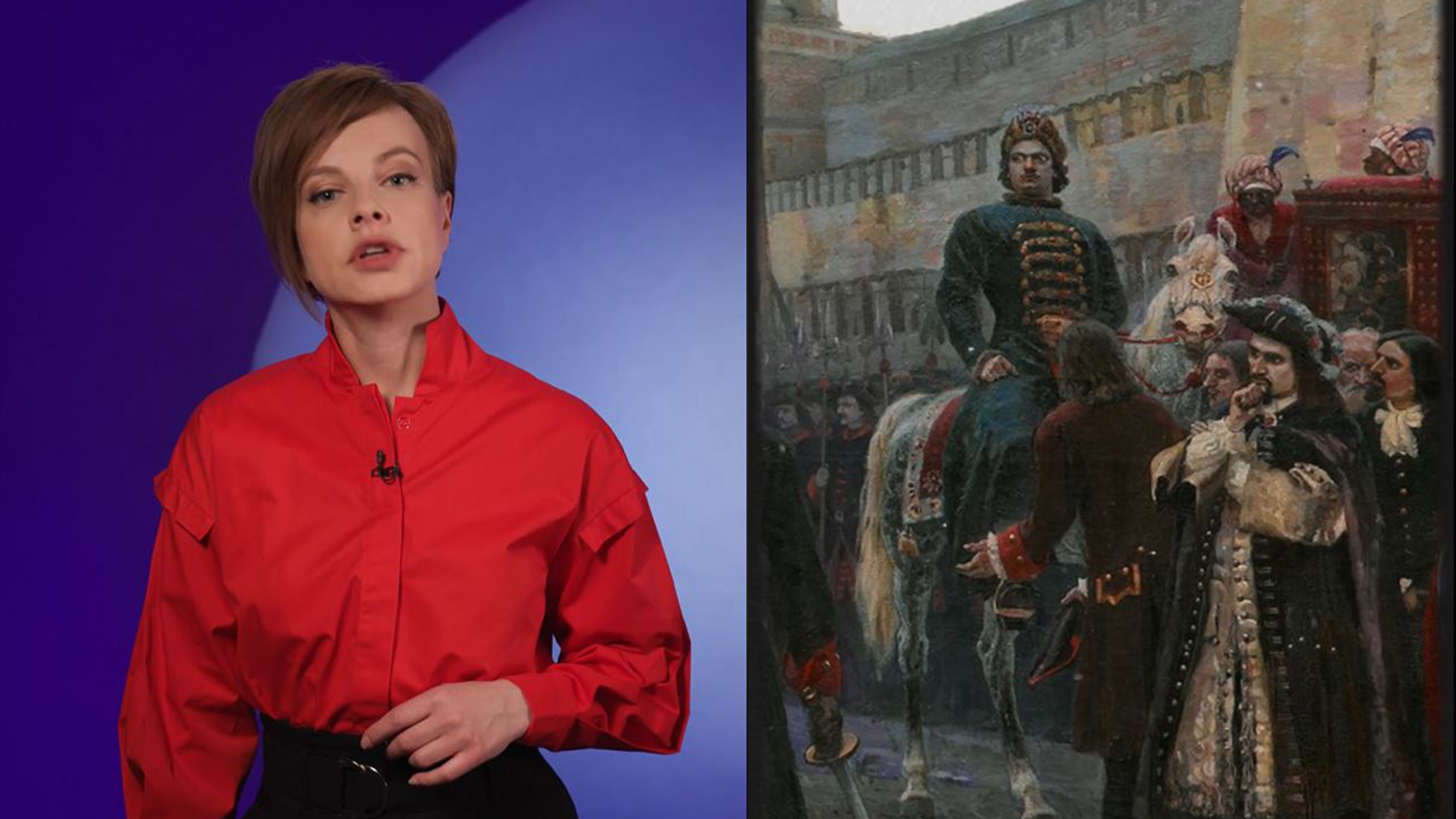

The wall of the Kazan Kremlin, probably constructed under Postnik Barma's supervision

The wall of the Kazan Kremlin, probably constructed under Postnik Barma's supervision

In 1555, architect Postnik Yakovlev was commissioned to build the walls of the Kazan Kremlin. The tsar ordered different officials, “and with them, the church and city master craftsman Posnik Yakovlev (italicized by us – RB)… to build in Kazan by spring a new stone fortress, and choose two hundred men of Pskov masons, wall builders, and wreckers, as many men as needed.”

Moreover, there’s another text about the construction of the Cathedral of the Intercession on the Moat that’s half a century older than the previous one. Here’s an important passage from the early 17th century Russian Chronicler from the beginning of the Russian land to Tsar Alexei Mikhailovich’s ascension to the throne: “The same year (1560) by the decree of the Tsar and Sovereign and Grand Prince Ivan, construction began on the votive church that was promised for the capture of Kazan, of the Trinity and the Intercession, and with seven chapels, which is called ‘on the moat’, and the architect was Barma with helpers.” Here, we clearly see that “Barma” is named as the sole leading architect.

Everything points to the fact that Posnik Yakovlev and Barma are the same person. How do we know this? In 1633, a note was left on a handwritten copy of the Sudebnik of 1550 (Russia’s main legal code at the time): “The Sudebnik of the stryapchy of the Solovetsky Monastery and Moscow man of service Druzhina the Tarutiev son, who is the son of Posnik, known as Barma, given to Ivan Maximov, Vologda’s customs podyachiy in the year [7]141.”

From this note we see that in the year 7141 from the creation of the world (year 1633 A.D.) a stryapchy of the Solovetsky Monastery and a man of service from Moscow, Druzhina, donated this copy of the Sudebnik to Ivan Maximov. Druzhina states that he is the son of Taruta, who was the son of Posnik, nicknamed Barma. He was, as historian Nikolai Kalinin supposed, the cathedral’s possible architect. Here, for a good reason, Druzhina states whose grandson he is.

It’s quite logical that the grandson of Postnik Barma held quite a high position in society. He was a stryapchy, meaning a representative in Moscow’s courts and prikazes of the Solovetsky Monastery, which owned a tremendous amount of land; it was an honorable and lucrative position. Aside from that, he was a man of service to the Moscow sovereign, in the capacity of a state official or a military man. If we carefully study and analyze all the facts then we will come to the conclusion that Postnik Barma is probably one and the same person, who was well-known and in high demand across Russia of that time because of his ability.

By the way, it’s quite peculiar that the name of Postnik was mentioned many times in Kazan’s scribe books after his assignment to that city. Those books are the lists of property owned by men in state service. It’s quite possible that this was the Postnik Barma who is the main subject of our investigation.

Was the builder of St. Basil’s Cathedral really blinded?

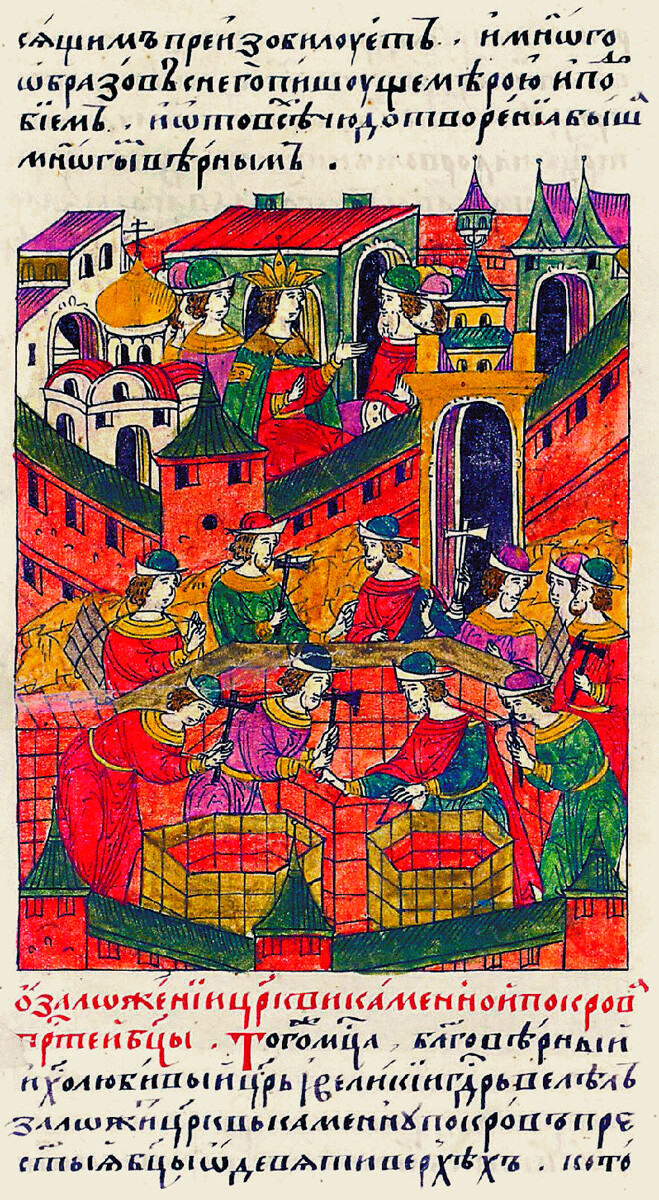

The Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed in 1855

The Cathedral of St. Basil the Blessed in 1855

It’s doubtful that such a respected man as Postnik Barma would be blinded after the magnificent work he had done. In addition, he continued to work after the construction of St. Basil’s Cathedral – in particular in Kazan. Aside from that, judging by the copy of the Sudebnik, which probably belonged to the grandson of Postnik, he was known and respected even after his death. That means it’s highly unlikely that he was blinded, exiled, or fell into any other type of disfavor with the Tsar.

Where did the legend of the blinding originate?

The legend about the “blinding of the architect” is unique in Russian history, and in fact there’s reason to suspect that it has European roots. This legend began spreading starting in the first half of the 17th century, but it became known to modern Russian readers thanks to a poem by the Soviet poet Dmitry Kedrin – “Architects” (1938) – which has the following lines: “And the benefactor asked: ‘Could you build another church, // prettier, more beautiful than this, I say?’ // And, shaking their heads, Replied the architects: ‘Yes, we can! Give an order, our sovereign!’ And prostrated themselves before the Tsar. // Then the Tsar ordered to blind these architects, // So there would be only one such church in his lands, // So in the lands of Suzdal, in the lands of Ryazan, and other // a better church than the Cathedral of Pokrov would never be built!”

As often is the case, readers are generally more susceptible to believe outlandish and ghastly stories. And when such a story is set to verse, then it makes an even deeper impact on popular perception. So it’s not surprising that the urban legend of the blinding, thanks to the poet Kedrin, got a new lease on life in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.