The 10-day king: How a Russian con artist became a European monarch

In his political program, Skossyreff proposed to Andorrans the modernization of their country, the abolition of taxes, a favorable regime for foreign capital, the opening of banks and casinos, and the development of tourism and sports. He opened for his subjects a new Andorran newspaper, as well as developed and published a new Constitution with a print run of 10,000 copies.

His proposals were ahead of their time and his vision is exactly what Andorra became after World War II: a country with its GDP based in large part on tourism, which offers banks substantial tax benefits and confidentiality, and which is a record holder in Europe in terms of income tax – it’s one of the lowest on the continent.

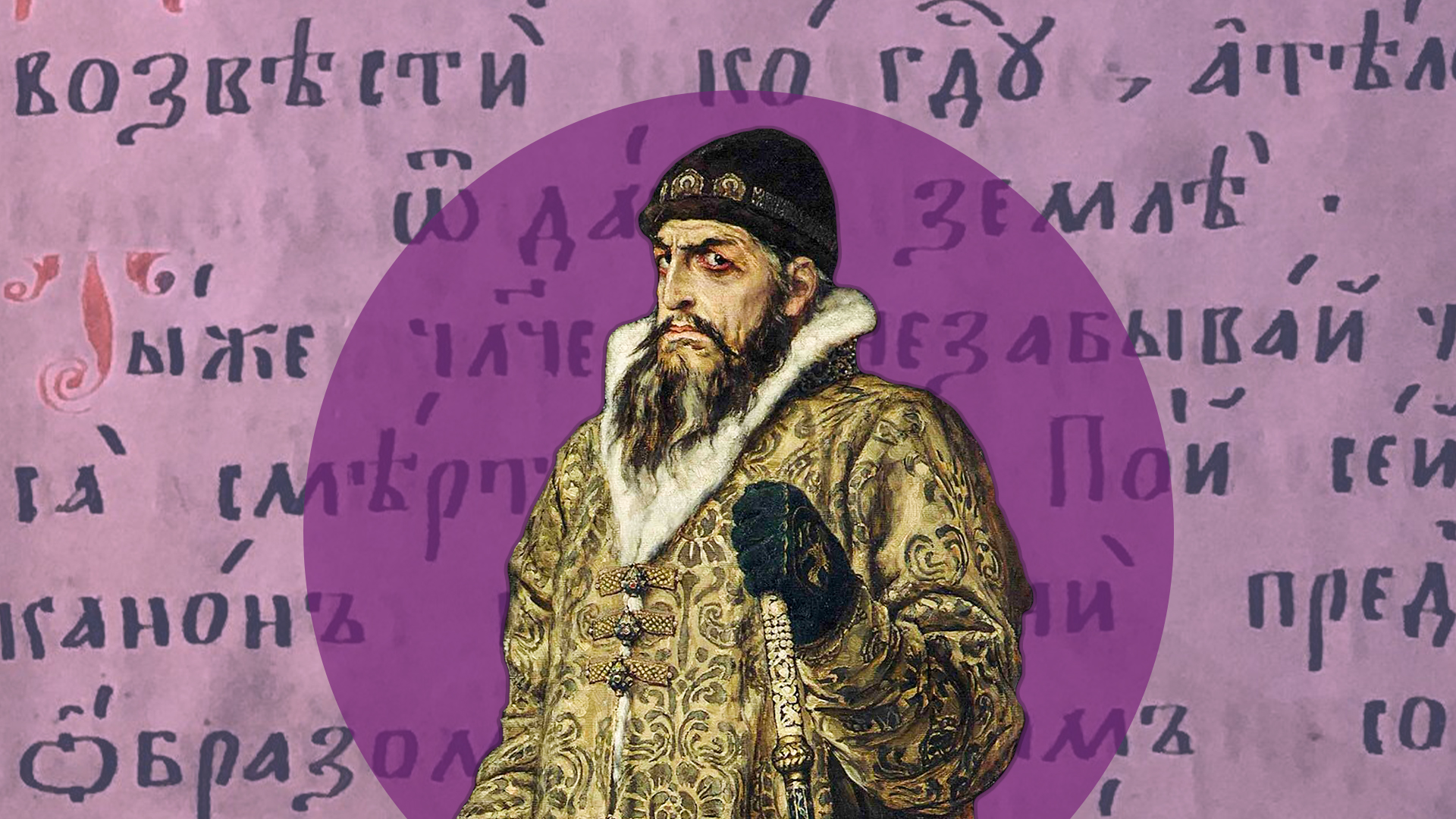

Skossyreff writing constitution

Skossyreff writing constitution

For a small principality, which from 1278 was formally subordinate to the head of France and the Spanish Bishop of Urgell, Skossyreff’s promises looked quite attractive. Especially since the year prior the country had been shaken by widespread unrest: the locals were unhappy with restrictions on voting rights. As such, the local government of Andorra – its General Council of the Valleys – ratified the contender’s program twice and proclaimed him King Boris I.

However, Skossyreff spent less than two weeks on the throne. The Bishop of Urgell was outraged by the decision to open a casino in Andorra, and he lashed out at Skossyreff in the press with much criticism. In retaliation, the new king released a proclamation in which he “waged war against the bishop”, although Andorra had no regular army of its own, apart from several guards. On July 20, the Catalan Guard arrested Skossyreff under the pretext of violation of immigration laws in 1933, when he originally arrived in Andorra but had been expelled. This time, he was taken to Barcelona and then sent to Madrid.

There, the disgraced ‘king’ came under the spotlight of the press and gave several interviews. Skossyreff stated that he “was motivated by the urge to protect the principality’s population from French exploitation.” Skossyreff explained his claims to the throne based on the fact that the French king, not the president, was the last legitimate heir. The descendant of the French king, Jean of Orleans, Duke of Guise, allegedly personally transferred his right to ownership of Andorra to Skossyreff; he even apparently had a letter stating this.

So, who really was this Russian con artist who managed to conduct such an outrageous and daring swindle?

Half-blood Count

Skossyreff’s gene for adventure was obviously given to him by his mother, Elizaveta Dmitrievna, who was born Countess Mavros. Already during her first marriage – under the family name Simonich – she gave birth to baby Boris on January 12, 1896, from retired cornet Mikhail Mikhailovich Skossyreff, who was 11 years her younger, writes Belarusian historian Leonid Lavresh.

The first time Elizaveta had married her own cousin for love – despite such marriages being prohibited – while her second marriage by the standards of the time was a misalliance. Mikhail Skossyreff was the son of a merchant of the 1st Guild, a hereditary supplier to the imperial court, but he had no noble title and had no right to pass it down to Boris, but his son later groundlessly called himself a noble.

From 1900 the family lived in Vilnius and near to the town of Lida (in modern Belarus), where Skossyreff spent his childhood. In fall 1915, as World War I raged, the region was occupied by German troops, and the family fled East. Most likely, Skossyreff went to the front as a volunteer and fought in a British armored division that operated on the Russian front. This, apparently, follows from a recommendation letter that the division commander Oliver Locker-Lampson granted to Skossyreff in 1924, writes Russian researcher of Skossyreff’s life Alexander Kaffka. Perhaps he was attached to the unit as a military translator. After the Revolution, Skossyreff asked for political asylum in the UK and served in the British armed forces for two years.

“Godson” of an English commander

Having gone overseas after World War I, Skossyreff strove to enter the circles of the wealthy and influential. At various times, he spread tales about himself that he had strong connections with the Russian imperial family, graduated from the elite Lycee Louis Le Grand and Oxford University’s Madgalen College, as well as claimed to be friends with the Prince of Wales and served at the court of the Queen of the Netherlands, from whom he allegedly received the title of Count of Orange, recounts Kaffka.

In reality, none of this was true. Skossyreff only truthfully enjoyed a connection with Locker-Lampson, and through him – with British intelligence, for which he possibly worked. Such a connection could at least explain why Skossyreff in the 1920s was easily able to avoid problems with the law, spurred by his bank check swindles and small-time thievery. Aside from that, there are stories that at the beginning of the 1930s the Spanish police started investigating Skossyreff in Majorca because of cases connecting him to cocaine.

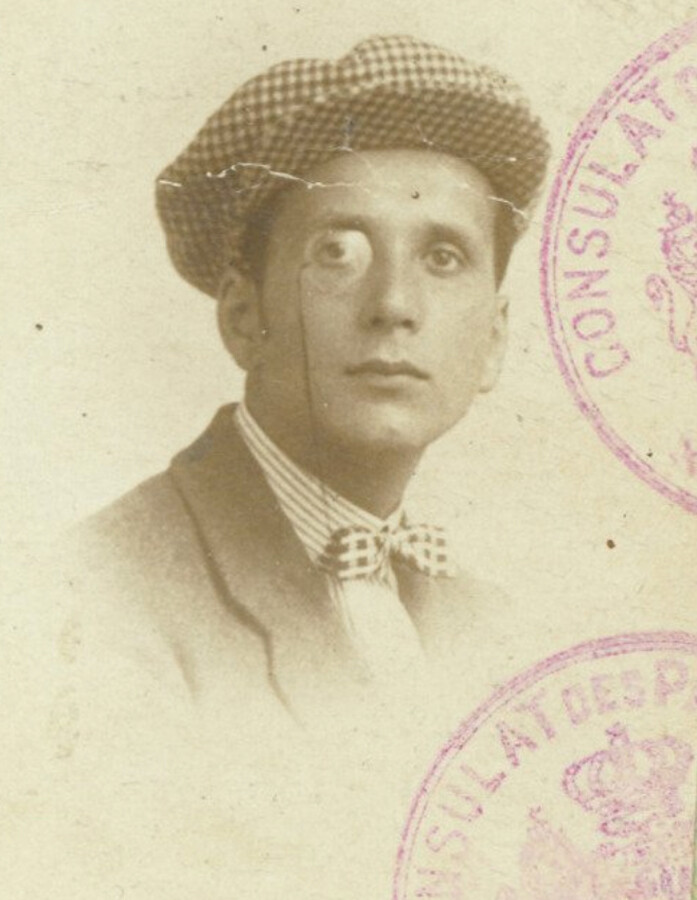

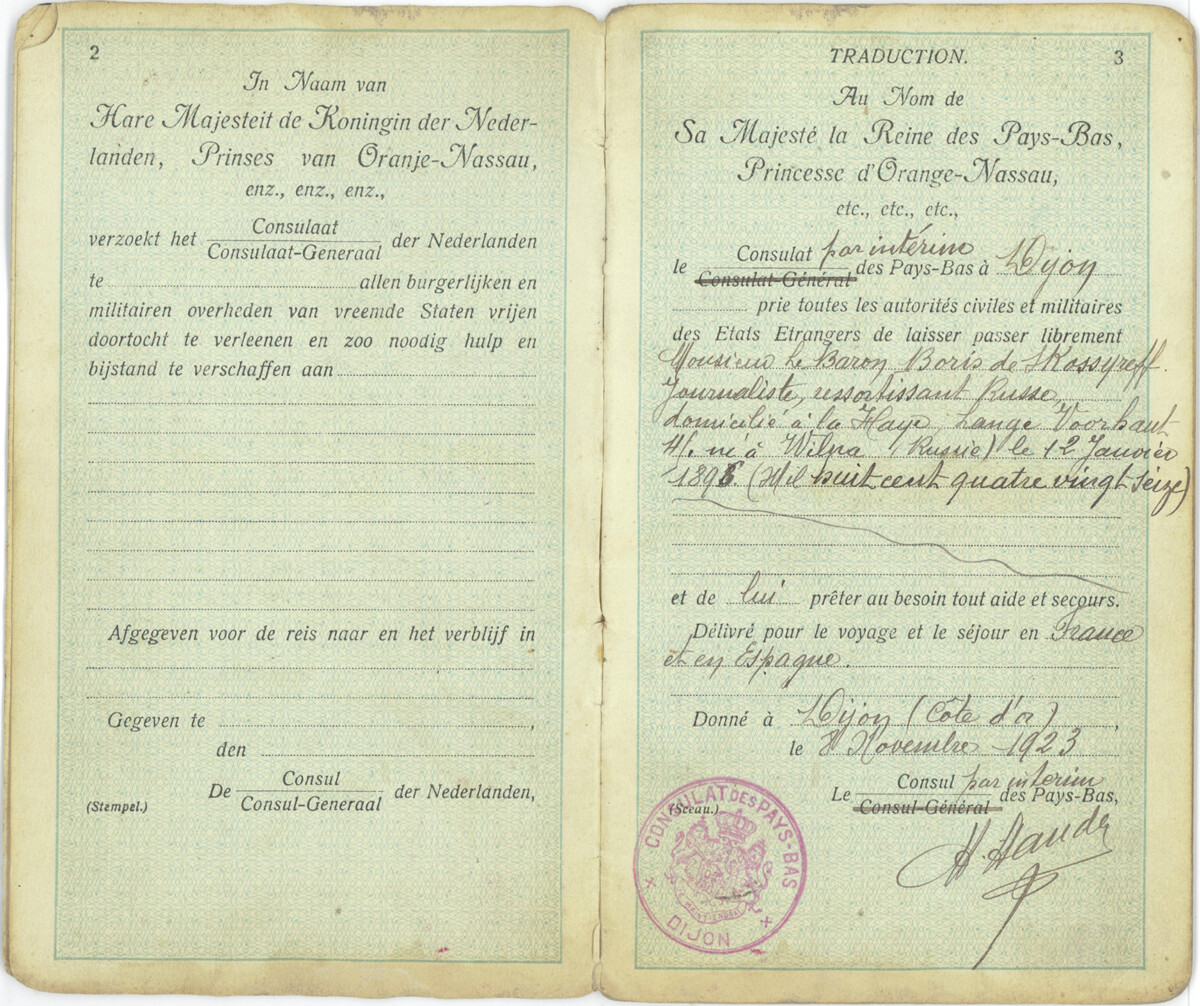

Boris Skossyreff Dutch Passport

Boris Skossyreff Dutch Passport

Meanwhile, during the 1920s Skossyreff managed to get a Dutch passport rather quickly. Trying to legalize his status in France, Skossyreff in 1931 married a woman who was 11 years his senior. However, the republic’s authorities refused his citizenship because of his scandalous reputation. Having a wife, however, didn’t prevent him from acquiring rich lovers and living at their expense. Also, he executed different underhanded enrichment schemes and carefully watched the political situation in Europe.

An agent of several intelligence services

As for Skossyreff’s Andorran adventure, it was financed by the Third Reich, claims Gerhard Lang, the author of the book Boris Skossyreff – A German Agent, The King of Andorra (“Boris von Skossyreff – Agent der Deutschen, König von Andorra”).

Berlin was interested in destabilizing the situation on the Iberian Peninsula, promoting the idea of independence from France and Spain among the Andorrans, and weakening the position of Paris. However, it’s unlikely that the Spanish discovered Skossyreff’s connection with the Germans: he was tried under a law on vagrants. In 1934 he was sentenced to jail for a year, but instead, was kept there for a month. Finally, the first and last Andorran king was deported to Portugal.

Boris I, king of Andorra

Boris I, king of Andorra

The next several years he spent in Portugal, Spain and France, eventually reuniting with his wife.

In 1939, the French interned Skossyreff in the Rieucros Camp in Mende, then transferred him to the Nazi concentration camp for foreigners in Le Vernet. In 1942, the Germans put him in a labor camp in the Berlin region. According to Lang, after some time he was employed as a translator in the 6th Armored Division of the Wehrmacht and received an officer’s rank.

The war ended for Skossyreff in American captivity. After World War II, Skossyreff settled in West Germany, but in 1948 he was arrested in East Germany by Soviet intelligence services: he had gone to the Soviet occupation zone “for business” (which is how smuggling back then was called). He was in Soviet camps until 1956, but afterwards he returned to the German city of Boppard, where he spent the rest of his days and died in 1989.

“It’s curious that the German authorities took immediate interest in him for having connections to Soviet intelligence services. They certainly didn’t understand how the chekists could release a person with such a rich biography as Skossyreff. But their investigation was fruitless,” Gerhard Lang notes.

A passion for hoaxes remained with Skossyreff well into his old age. In 1982, a book was published called The Man in Yalta: A Secret Order of Hitler to Boris von Skossyreff, which claims that Skossyreff during the Yalta Conference persuaded the Allies not to drop a nuclear bomb on Germany. But even this, according to Lang, was a lie.