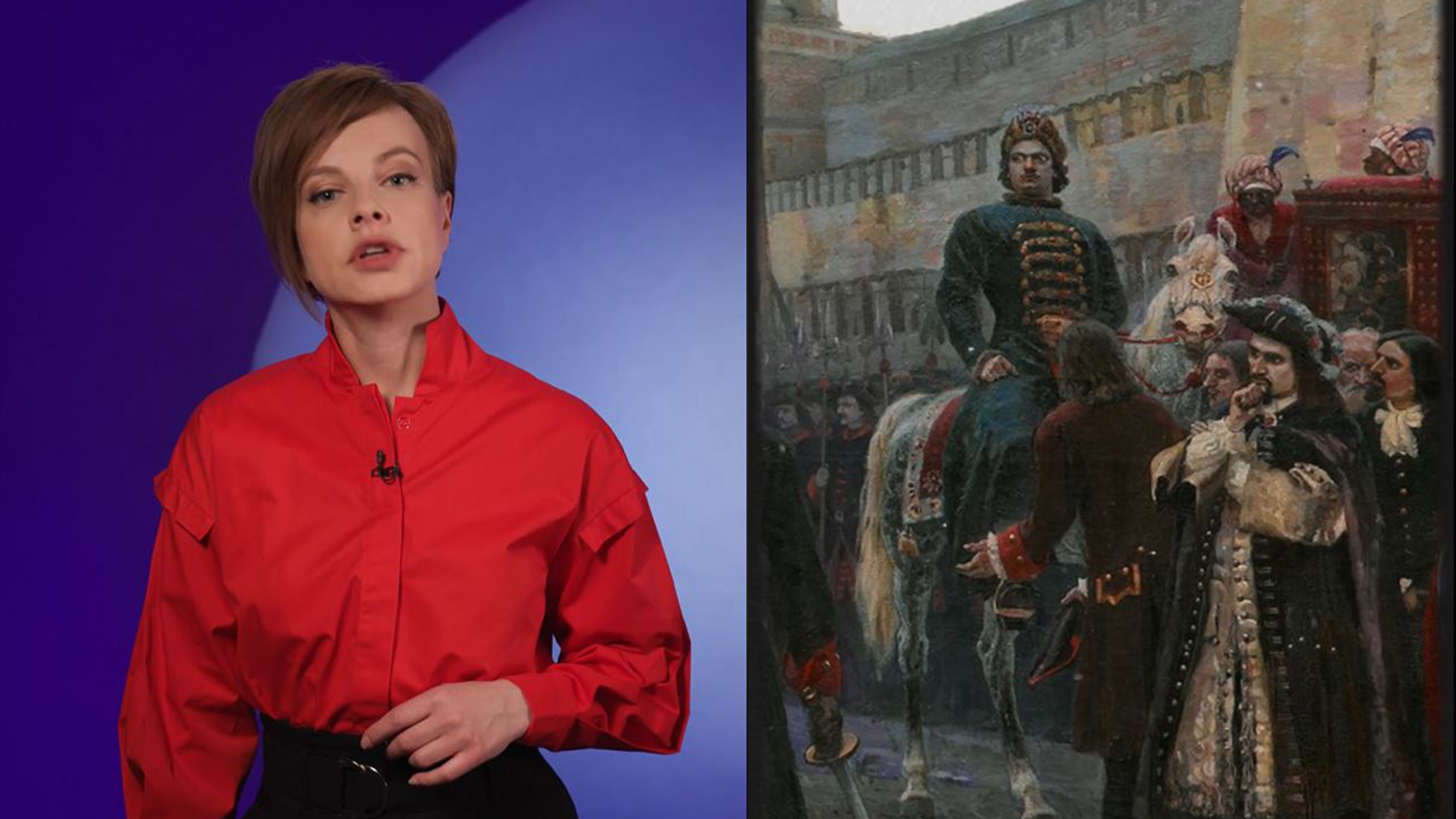

Meet the Bogatyrs, Russia’s supermen

Tales about bogatyrs, the strong men of the distant past, are among every Russian boy and girl’s favorite bedtime stories. Ilya Muromets, who laid on a stove for 33 years, and then was miraculously healed to help Prince Vladimir save the Russian lands. Alesha Popovich, who fights Tugarin the dragon, or ancient bogatyr Svyatogor, trapped by Earth, because of his power. These heroes seem to have “originated” in the Russian lands before Christianity was adopted.

Where did the word ‘bogatyr’ come from?

"Vityaz' at the Crossroads" by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1882

"Vityaz' at the Crossroads" by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1882

The very word ‘bogatyr’ is not of Russian origin. It was borrowed from Turkish languages, where ‘*baɣatur’ means ‘hero; warrior; war commander’. In the Russian lands, such outstanding warriors were called khrabr (храбр, ‘brave one’), vityaz (витязь, ‘warrior’), or molodets (молодец, ‘young one’). Why did the Russians need a Turkish word then?

Among the Mongol-Tatars, the foremost warriors were called ‘bogatyrs’ and Russians adopted this name for their heroes, to underline that they were not weaker than the Mongol bogatyrs. Retrospectively, in Russian tales, the heroes were also named bogatyrs.

What sources tell about bogatyrs?

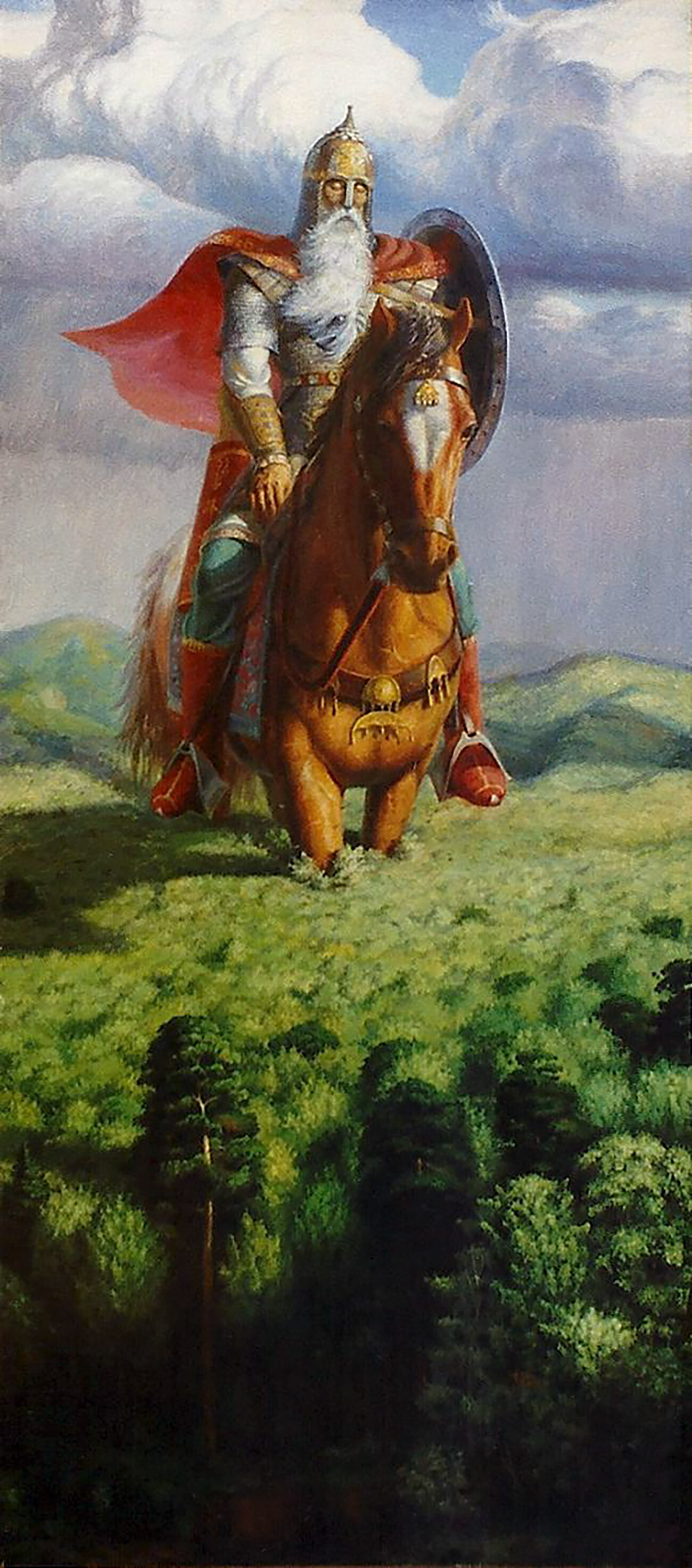

Svyatogor

Svyatogor

Russian bylinas were epic songs dedicated to famous historical (or pseudo-historical) events in the Russian past. The bylinas were sung by generations of bards and transferred orally. The first time they were recorded and issued as a book was in 1804 and they were studied and collected throughout the 19th century. There are several hundreds of bylinas known to historians and they are divided into the Kievan series, the Novgorod series and All-Russian bylinas, based on where the action took place.

The bogatyrs who starred in the bylinas are not exact depictions of certain real heroes of the past. They are more like collective images of archetypal heroes that incorporate stories about different warriors, created on the basis of ancient myths.

The ‘elder’ bogatyrs

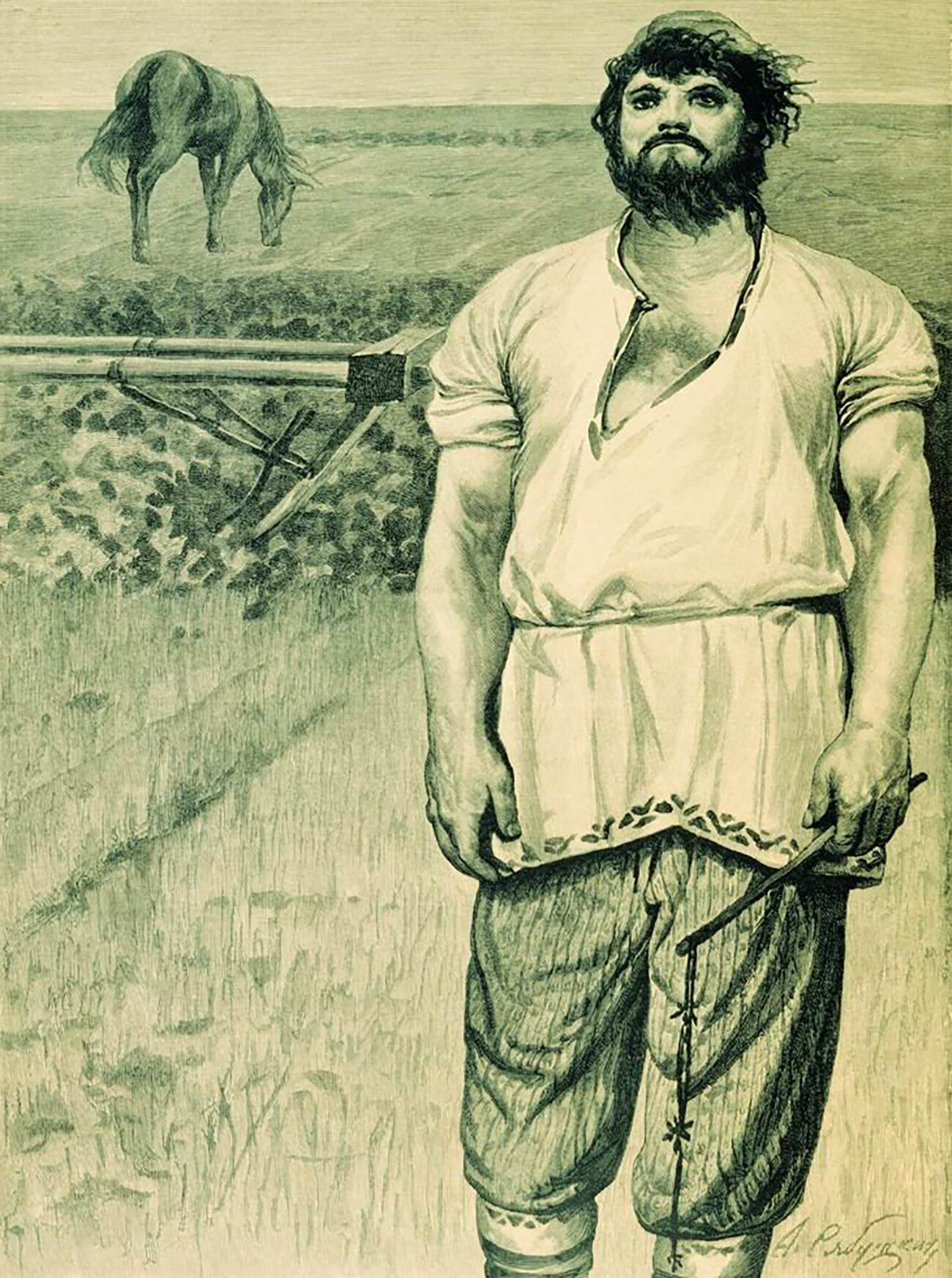

Mikula Selyaninovich by Andrey Ryabushkin

Mikula Selyaninovich by Andrey Ryabushkin

The bylinas mention dozens of different Russian bogatyrs. There are three elder bogatyrs: Svyatogor, Volga Svyatoslavich and Mikula Selyaninovich.

Svyatogor is the oldest and strongest bogatyr. Historians and philologists agree that Svyatogor is most probably a pre-Christian hero of Russian lore. Svyatogor is a huge giant who lives in the Holy mountains. When he walks, Mother Earth shakes, forests sway and rivers overflow their banks. Various bylinas tell that Svyatogor is either trapped in the earth (after trying to lift all the Earth’s weight collected in a bag) or immobilized in a stone coffin. In any case, Svyatogor is a personification of some ancient all-encompassing power. He’s too strong and too heavy for Earth to carry him.

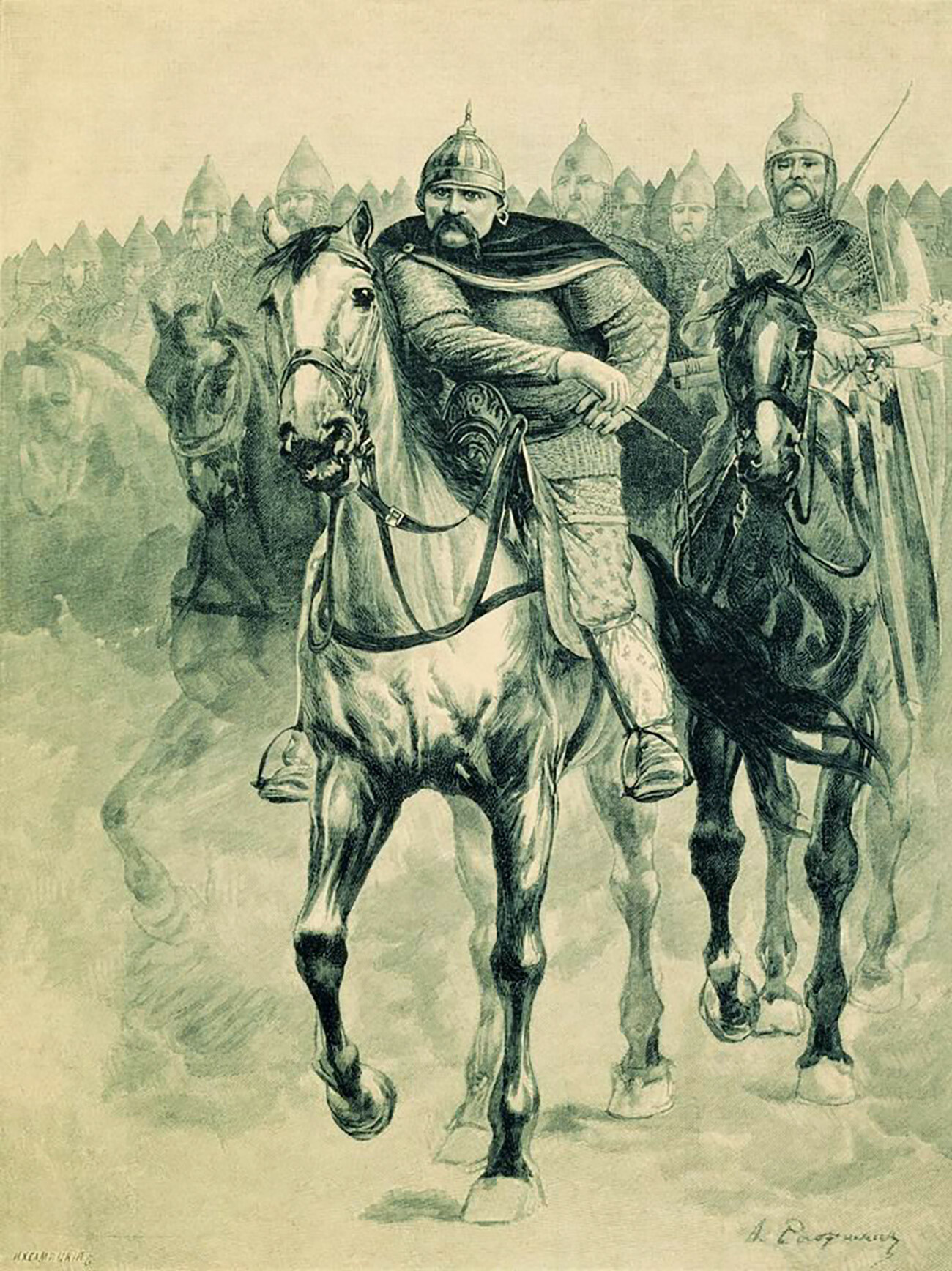

Volga Svyatoslavich, by Andrey Ryabushkin, 1895

Volga Svyatoslavich, by Andrey Ryabushkin, 1895

Volga Svyatoslavich is another pre-Christian bogatyr. His mother was a princess and his father was a magical serpent, hence Volga’s ability to transform himself into various creatures and understand the language of animals. There are many tales about Volga’s conquest of the foreign lands, Indian or Turkish.

READ MORE: What did the Slavic 'Justice League' look like?

Mikula Selyaninovich is the ultimate peasant bogatyr. His patronymic, Selyaninovich, means ‘son of a villager’ and he’s invincible, because “mother Earth loves his kin”. It is Mikula who gives Svyatogor a bag with all the Earth’s weight, that Svyatogor can’t lift. Mikula’s name is a variation of the name Nikolay (Nicholas) and, in Russia, Saint Nicholas is revered, to the present day. Historians argue that Mikula Selyaninovich could be some kind of ancient peasant pagan god worshiped later under the name of St. Nicholas.

The Three Bogatyrs

"The Bogatyrs" by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1881-1898

"The Bogatyrs" by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1881-1898

All the other bogatyrs are considered to be “junior” bogatyrs. There are dozens of them in the byliny and, frankly speaking, most Russian people don’t remember them by now. But everybody knows Viktor Vasnetsov’s seminal painting ‘The Bogatyrs’. Taking almost 20 years to paint (1881-1898), it embodied the passion the Russian society felt towards the natural lore of the Russian land. The bogatyrs depicted are the most known heroes of the bylinas, Dobrynya Nikitich (left), Ilya Muromets (center) and Alesha Popovich (right).

Ilya Muromets is actually the most famous of all Russian bogatyrs. He is considered to be the “protector of the Russian land”. His story, told in various bylinas, is very archetypal for Russia. For the first 33 years of his life, Ilya couldn’t walk, because of some unknown disease. Once, when he was alone in his home, three traveling pilgrims came asking for water. “I can’t move,” Ilya said, but the pilgrims insisted that he get up and fetch them water. Unexpectedly, Ilya got up and brought a bucket of water. The elders instructed him to drink the water and he was healed. After that, Ilya felt enormous power and went to Kiev to help Prince Vladimir protect the Russian land, the bylinas say.

The biographies of Dobrynya Nikitich and Alesha Popovich are close to each other in the bylinas. They both fought evil serpents: Dobrynya fights Zmey Gorynych, while Alesha fights Tugarin Zmey. They both protect the Russian people and are brothers to each other. Both bogatyrs are described as cultured and literal. Dobrynya speaks 12 languages and Alesha plays gusli, a Slavic kind of zither (in the painting, you can see gusli slung over Alesha’s back on the right).

Were the bogatyrs even real?

Iliya Pecherskiy's relics in the Kiyv-Pechersk Lavra

Iliya Pecherskiy's relics in the Kiyv-Pechersk Lavra

The bylinas are not some complete list or collection, they were orally told for centuries, they have innumerable variations and additions. By far, not all of the bylinas have been recorded. So, the tales of the bogatyrs comprise real events of the past with fiction and it’s also like that with the heroes.

For example, it is considered that Alesha Popovich of the bylinas was really Alexander Popovich, a boyar from Rostov Region, who died in the Battle of Kalka in 1223. However, by the 13th century, Alesha Popovich was already a famous hero of the lore, so the real person was apparently influenced by the lore and not vice versa.

Same goes for Ilya Muromets. It is widely believed that his real prototype is Saint Ilya Pecherskiy, a monk in Kyiv Pechersk Lavra, who died in 1188. His body is stored in the caves of the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra and the burial is dated by historians to the 12th-13th century.

In 1988, medics conducted an examination of the relics of St. Ilya. The study showed that he was a large man and had a height of about 177 cm. What is really remarkable is that the body showed signs of spinal disease – which coincides with the story of Ilya Muromets, who lay on a stove for 33 years. The bones of the skull are unusually thick and the wrists and collarbones are much larger than the average in humans. The cause of death was probably a blow from a sharp weapon (spear or sword) to the chest.

Could it be that Saint Ilya Pecherskiy was really Ilya Muromets’s prototype? Be it so or not, Ilya Muromets is considered the patron saint of the Russian Strategic Missile Forces and the Russian Border Guard Service. And he is still on the watch.