Göring’s embrace & lunch with an executioner: The story of a Soviet interpreter in Nuremberg

It seemed that Stupnikova stood no chance of getting a job at the exceptionally important Nuremberg trials: being a non-partisan daughter of the repressed “enemies of the people”, she couldn’t simply join the Soviet delegation. However, when the court proceedings started, it became clear that there was a severe shortage of translators on the Soviet side. The NKVD was put in charge of an urgent search for specialists, with Stupnikova being summoned to General Ivan Serov, deputy of Lavrenty Beriya, head of the People’s Commissariat.

“The meeting was short: ‘I’ve been told that you can conduct simultaneous interpretation’. I kept silent, as I didn’t have the faintest idea about what the term ‘simultaneous translation’ stood for. At the time, what I only knew was written and oral translation,” Tatiana Stupnikova wrote in her memoirs ‘Nothing but the truth’.

Two days later, Tatiana and her three colleagues landed in Nuremberg. What awaited her was a year of work at the key court trial of the Nazi criminals. Stupnikova returned home only in January, 1947.

Meeting her future husband

Having worked late hours on her very first day, Tatiana didn’t notice her colleagues leave the room and head to the bus, which was to take them to their villas in the suburbs. She, thus, had to look for the way herself, but the corridors of the Palace of Justice appeared to resemble a real maze. Having completely lost her way, Stupnikova tried opening a door with no sign on it, but was instantly confronted by two American military policemen, who grabbed her arms and took her to a prison room, according to her memoirs. Tatiana was mostly concerned about the bosses of the Soviet delegation learning about the incident and seeing the elements of crime in it - a “covert” meeting with foreigners. It was something one could spend years in labor camps for.

American military police

American military police

However, soon enough, accompanied by three American military men, her colleague, translator Konstantin Tsurinov, burst into the room. “‘I’ve found you at long last!’ - these were his first words, which we later often repeated to each other,” Stupnikova recalled their first meeting with her future husband.

“The last woman in Göring’s arms”

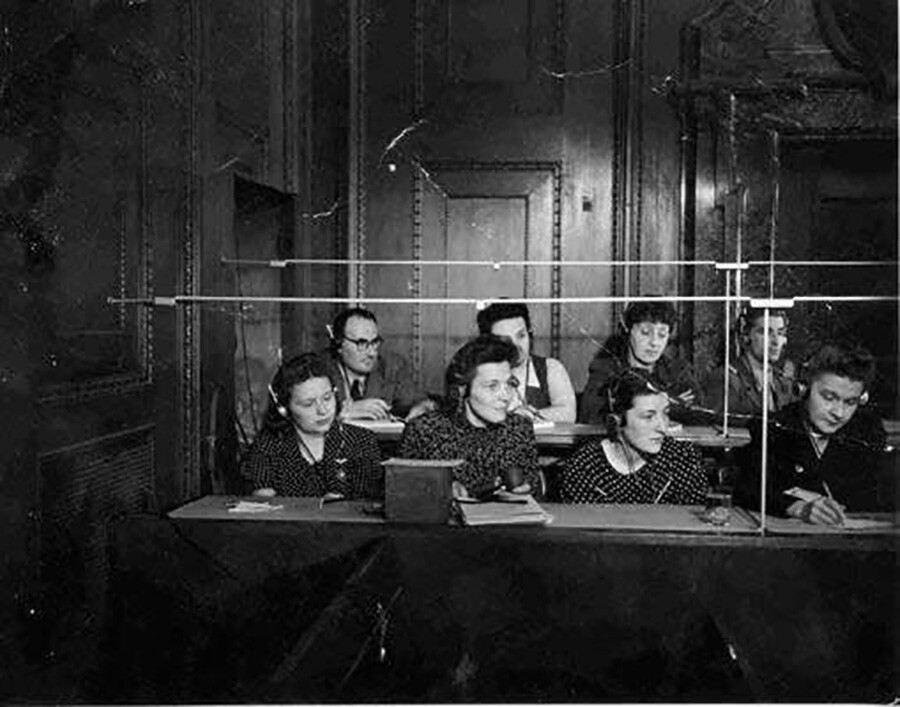

The translators’ “aquarium”

The translators’ “aquarium”

In early August of 1946, Tatiana Stupnikova was hurrying into the translators’ “aquarium”. While she was running along the corridor, she accidentally slipped and would have fallen down, had “someone big and strong not held her”.

“When I regained my calm and looked up at my rescuer, I saw Hermann Göring’s smiling face very close to mine. He whispered in my ear: ‘Vorsicht, mein Kind!’ (‘Be careful, my child!’),” Stupnikova once recounted.

When Tatiana entered the room, a French correspondent came up to her and told her in German that she would be the wealthiest woman in the world then: “You were the last woman Göring held in his arms. Don’t you understand it?”

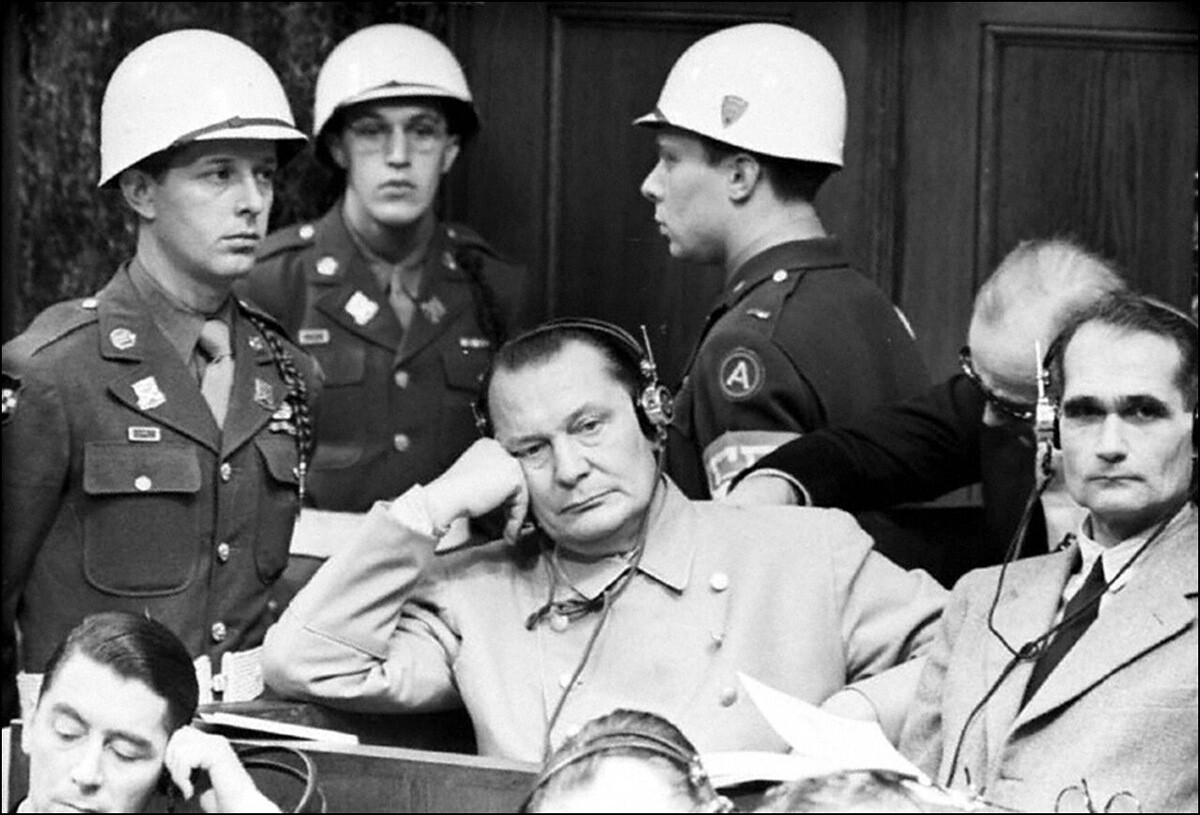

Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trial

Hermann Göring at the Nuremberg trial

Yet, Stupnikova failed to appreciate the Frenchman’s joke. On October 16, 1946, Hermann Göring, who had been sentenced to death by hanging, committed suicide two and a half hours before the execution, by taking in potassium cyanide.

Lunch with an executioner

There was self-service in place in the canteen of the Palace of Justice and, thus, there were never enough seats for everyone. One day, holding a tray in her hands, Tatiana caught sight of a table, with only an American senior sergeant sitting at it. The Soviet translator took a seat next to him - no other places were vacant. The man struck her with his obligingness: he brought a pile of napkins, which their table lacked, passed her the salt and, as she recalled, made it clear that he would do anything she would ask for.

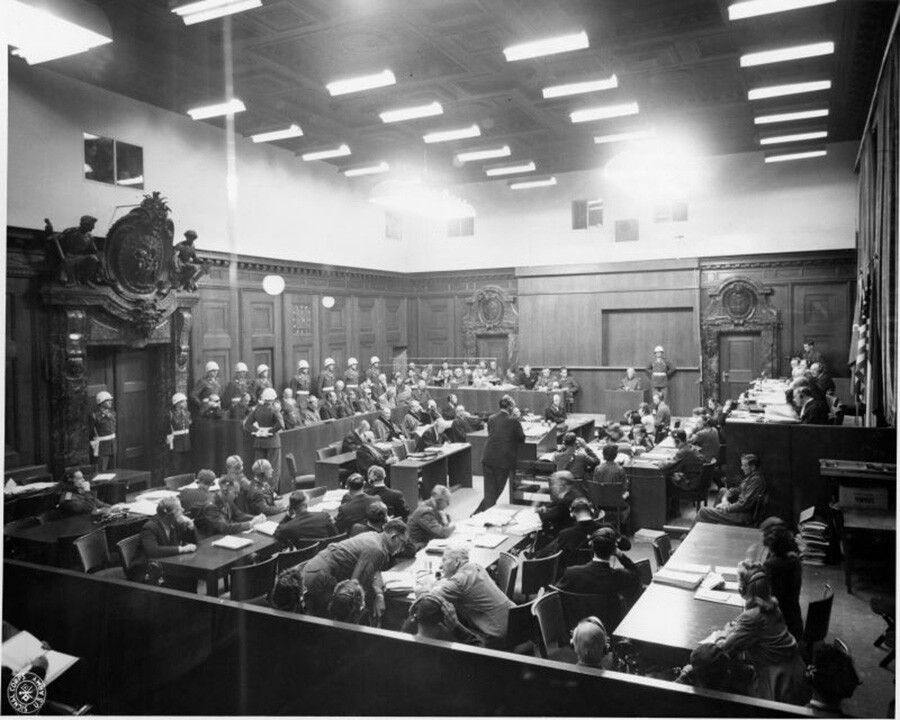

Nuremberg's courtroom

Nuremberg's courtroom

Meanwhile, Tatiana’s compatriots were sitting nearby and were making some mysterious signs at her, which baffled the translator. The senior sergeant then brought four portions of Tatiana’s favorite ice-cream - something that caused wonder, since second helpings were reluctantly given in the canteen. This added to Tatiana’s growing suspicions that there was something wrong going on. She couldn’t help eating the two portions of the dessert, though. Then, she stood up and left, despite the man persuading her to stay a bit longer.

American John Woods

American John Woods

In the working room, her colleagues told her he had just had lunch with John Woods, a hereditary executioner. Although the military tribunal hadn’t yet finished its work, Woods had arrived in Nuremberg well in advance to perform checks of the gallows.

Snail as a talisman

Before the opening of a new court session, Tatiana was approached by two French journalists and handed a big living brown snail; such snails typically thrive in German and French vineyards. According to them, the snail was the best talisman against all misfortunes during translation. Tatiana took the mollusk and hurriedly walked to her workplace. Having put it into a glass of water, she got down to work.

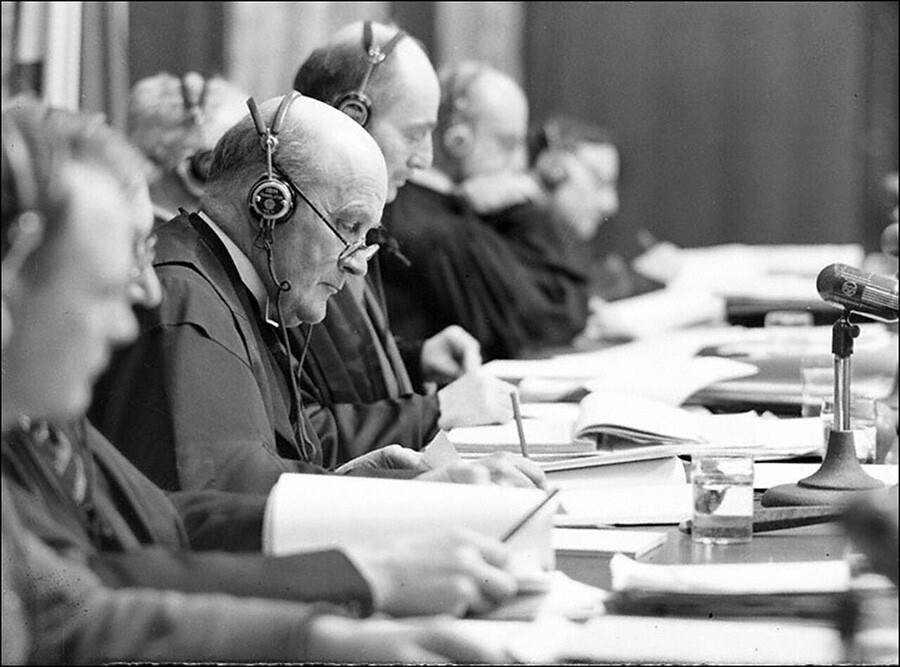

Judges at the Nuremberg Trials

Judges at the Nuremberg Trials

Several days laters, one of the local papers published a picture of Stupnikova with the snail. The description read: “The Soviets haven’t managed to do away with superstitions. The Russian translator can’t part with her talisman.”

The Soviet people were supposed to treat superstitions most negatively, as the latter were deemed as relics of the past. Yet, the incident went unnoticed, with the snail coming to Moscow together with the translator in the end.

Life after the Nuremberg trials

On October 1, 1946, the International tribunal came to an end. For the next three months, the Soviet translators lived and worked in Leipzig, which lay in the Soviet occupation zone. They were to edit shorthand reports, while comparing translations to the original sources.

The trial of the Nazi war criminals

The trial of the Nazi war criminals

In early January 1947, the translators moved to Berlin and then back to Moscow. On her return, Tatiana started looking for a new job, which she could combine with her postgraduate studies. Such an option was offered in the ministry of cinematography: minister Ivan Bolshakov was in urgent search for specialists who would translate trophy movies.

Tatiana was told that she would work for Joseph Stalin himself. Apart from translation, the task was to select films with no love scenes or politics. The movies themselves had to be exclusively black and white, as Stalin feared the “adverse impact” of colorful images on health.

One day, the commission failed to find an appropriate English or French film during working hours and everyone pinned their hopes on Stupnikova, expecting that the last film she reviewed would meet the criteria. The already exhausted translator nearly missed the moment a colorful scene popped up on the screen - it turned out to be a movie in a movie. That was how Tatiana avoided a potentially fatal mistake.

Recalling her work at the Nuremberg trials, Tatiana Stupnikova pointed out:

“For a budding simultaneous interpreter, there is nothing more useful than constant practice in a translation booth, with headphones on and a microphone in their hands.” So, there was apparently no better practice for a translator from/to German and English than the military tribunal, both in terms of workload and content.