Why did Russian priests participate in pagan rites?

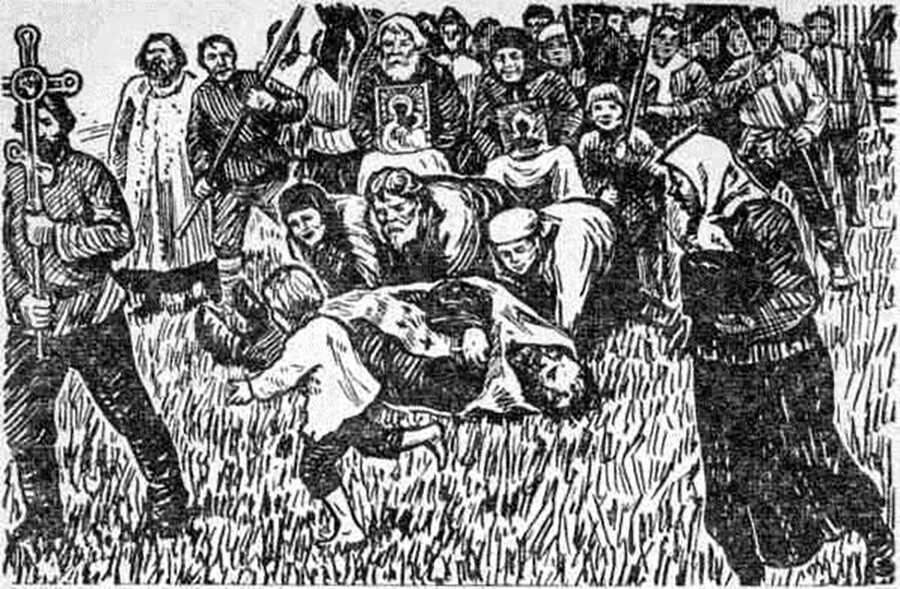

“St. George’s dew is from the evil eye, from seven ailments,” Russian peasants used to say. They believed the morning dew collected on St. George’s Day (April 23, O.S.; May 6, N.S.), the day the earth “opens” for the first time in a year, is “sacred” and can heal diseases. Peasants often asked their village priest to poke around the village field in the morning on this day – “so that the sheaves shall be heavy”. “If the clergy refused to do so, they were knocked down on the ground and rolled forcibly,” writes historian Tatiana Agapkina.

Father and the peasants

Razmaritsyn A. P. "Memorial service in a village"

Razmaritsyn A. P. "Memorial service in a village"

A village priest had to seek ways to live in peace and harmony with his parish – his own village neighbors. From the late 18th century, priests were recruited only from the clergy – ordination of townspeople and peasants stopped in 1774. From the 1760s, the clergy was exempted from all taxes and duties to the state, except for the maintenance of the metric books. However, the clergy could not leave the clerical ranks by their own free will.

Priests were appointed to the various villages and hamlets not by their choice, but by the Most Holy Synod of the Russian Empire. The village priest was usually a man from elsewhere and to establish relations with his parish was the most important goal for him.

Of all the villagers, the priest was the one most feared and respected. Every peasant who met him would take off his hat and ask for a blessing. But, the peasants needed a lot from the priest, too. As protopriest Alexander (Rozanov) (1825-1895) wrote in his ‘Notes of a Countryside Priest’, a peasant “is busy working during the day, especially in summer, and he has no time to invite the priest to his sick relatives during the day; therefore, he goes after him mostly at night, paying no attention to the weather”.

A village deacon fetching water, 1900s, Russia

A village deacon fetching water, 1900s, Russia

It is not only a terrible sin to refuse to give a dying person Holy Communion, it is also a gross violation of church rules. But often, it seems to the elderly that they are leaving this world far in advance. Therefore, Father Alexander explains: “A priest at any time of the day or night and in any weather should be ready for the requisitions (baptisms, confessions, etc.), in spite of his own illness. In every office, there is a certain hour of work and a certain hour of rest. The priest has no such hour.”

The priest was often not richer than the peasants – his main income was often farming. Salaries of rural clergy, as Elena Panfilova calculated in her article ‘Material provision of a parish priest in the late 19th – early 20th centuries’ were quite miserable: “On average, a priest would get 300 rubles, a deacon 150 rubles and an acolyte – a mere 100 rubles a year,” Panfilova writes. By comparison, in 1913, the salary of a common worker was 20 rubles a month. For today’s money, the priest was supposed to receive 500-1,000 euros a year, but even that money was not always paid.

The priest, therefore, collected payment for the services – prayers for the health of a particular person, memorial services, etc. The size of the funeral services was not fixed and depended on the popularity of the priest with the parish. Of course, the priest had to be paid for weddings and funerals and these revenues were the most considerable.

Vasiliy Perov, "Tea time in Mytischi," 1862

Vasiliy Perov, "Tea time in Mytischi," 1862

A rich parish meant a rich priest. And in medium-sized and poor villages, the priest and the priestess could plow, make crafts or keep an apiary. Some gave their small plots of church land to the peasants to cultivate and took from them a “tax” in the form of food products. Regular gifts from the community to the priest on major feasts were also common. In Kursk Region, for example, there was a widespread custom of “carols” for the priest, in which the priest would go to the huts and collect Christmas food gifts.

But, for such a poor priest, his village would stand by his side. Noting the positive qualities of such priests, peasants said that one could go to the priest at any time and in any weather and that he himself had a simple, peasant house. If you can’t send a horse for him, he will go to accept the confession of a sick person on foot. He doesn’t ask money from the poor, he serves on credit. With him you can always have a shot of vodka and he teaches your children the law of God. But the state and provincial nobility, who were also served by a village priest, needed something else from him.

Father and the state

Vasiliy Perov, "Easter Procession in a Village," 1861

Vasiliy Perov, "Easter Procession in a Village," 1861

Beginning with the reign of Nicholas I, new responsibilities were assigned to the priests. The government saw them as agronomists, rural teachers and physicians. The peasants, who were disappointed in the folk healers, could also go to the priest for advice or a “healing” prayer – there were no rural doctors until the second half of the 19th century. The priests were always literate and read newspapers, so they were also the main source of political news for their parish.

READ MORE: How did single women survive in Tsarist Russia?

The priest also had to keep the metric books and, with the growth of national statistics, to give various information – about the number of births, illegitimate ones, children with deformities, number of marriages, number of single and widowed people, etc. The priest also had to observe the weather, have barometers and thermometers and keep daily records. In case of epidemics and epizootics, it was up to the priest to oversee the anti-epidemic measures. He was also expected by the fire department to insist that there be a tub of water and a bucket of sand in every village hut. And the priest was also the village’s only psychologist, a conciliator of conflicts between spouses and neighbors. And everyone expected the priest to find time and offer help.

Akim Karneev, "The baptism"

Akim Karneev, "The baptism"

Refusal by the priest to carry out the orders of the state could lead to a complaint to the Consistory, the governing local body of the church, and, from there, would come a paper marked “for immediate execution”. It was pointless to put up a fight with the diocesan bosses – any provincial local bishop had more authority over his clergy than the tsar himself had over his officials and a bishop could easily dismiss a disobedient clergyman.

But what if the priest’s patience was running out because of the peasants’ constant requests and worries? If there is a poor harvest, the priest is to blame – he didn’t pray right. If the state applied new taxes, all the blame went on the priest – because he read the laws aloud from the church's ambon.

Father and the paganism

Rolling a priest in the dew, an archive drawing

Rolling a priest in the dew, an archive drawing

Unlike the “good” priest, who went along with the peasants, priests who were especially educated and obeyed the statutes of the church were not popular. Such priests were against folk beer brewing or communal meals on church holidays, for instance. The “strict” priests fought pagan customs like veneration of sacred stones, trees, streams, etc. They demanded that their flock know their prayers and rituals and were strict about blasphemy.

To insult and abuse a priest was considered a terrible sin. Popular superstitions united the image of the Christian pastor with the image of the ancient sorcerer – it was believed that a priest who was rightfully ordained, knew texts and rituals, had special powers which allowed him to influence life itself. This is indicated, in particular, by an ancient omen: “A meeting with a person of spiritual rank and especially with a priest, takes away good luck or promises misfortune in the way.”

Mind that the priest in the village accompanied and oversaw all births and deaths. He blessed marriages and baptized children. It was believed that he could “heal” diseases with prayer. In general, he had all the attributes of a sorcerer or priest and, therefore, the peasants, promising him rich gifts, asked and persuaded the priest to participate in many relic pagan rites, such as the “rolling in the dew”.

“The custom of ‘rolling’ the clergy in the dew is not only an echo of the ancient ‘rolling’ of the priest (magus) as a manifestation of agrarian magic,” writes famous philologist Alexander Bobrov in his article ‘Rolling in the dew as a pagan sacrament’ – “but also a fact of contemporary religious polemic, a violent introduction of a representative of another, Christian faith to pagan rites still in use among the people.”

The priest was attributed the ability to “open” the borders between the worlds. Therefore, if someone in a village had a difficult birth, the priest was asked to “open the gate” in the church, so that the childbirth could proceed better. Of course, the peasants could go to the priest if they thought a spell had been put on them. The “strict” priest would lecture them on superstition and impose penance, while the “kind” priest would read “cleansing” prayers and let them go with God.

Baptism of Jesus is a Great Feast in the Russian Orthodox Church. However, dipping into icy waters on the night of this feast isn't a Christian rite.

Baptism of Jesus is a Great Feast in the Russian Orthodox Church. However, dipping into icy waters on the night of this feast isn't a Christian rite.

Sometimes people even turned to the priest to call for rain – the priest had to be dipped into the river or dipped into water (a typical “sympathetic” magic). It was best if the priest agreed to perform the water ritual wearing his Orthodox attire.

If a witch doctor died in the village, the priest was asked to be present when a stake of aspen was driven into the corpse so that he would not rise from the coffin. A priest might also be asked to be present when the bodies of suicidal persons were pulled out of the ground and thrown into water, a popular rite against drought. Of course, diocesan authorities could severely punish those who participated in such rites; but the peasants, however, would not be in debt, of course, if it rained in the end and the harvest was good. But even if it didn’t – ‘God’s will be done’ were the words of the priest, whose main task was to maintain peace and harmony in the village.