How the Moscow Kremlin was built and rebuilt (PICS)

The first walls and the first fortress of Moscow were a typical example of Slavic fortification architecture. They were fortifications made of wood and earth. Russia began building stone fortresses later than some European regions – mainly due to the excess of timber around.

The first fortifications stood in Moscow until the year 1177, when they were burned down in a feud between princes. Then, new fortifications were erected – an earthen rampart (built from the earth dug up for a ditch) with an oaken palisade on top. The ditch’s width reached 18 meters with the depth of the ditch approximately 5 meters. The rampart itself was 7 meters high. This version of Moscow’s walls survived until 1238, before being destroyed by the Mongols.

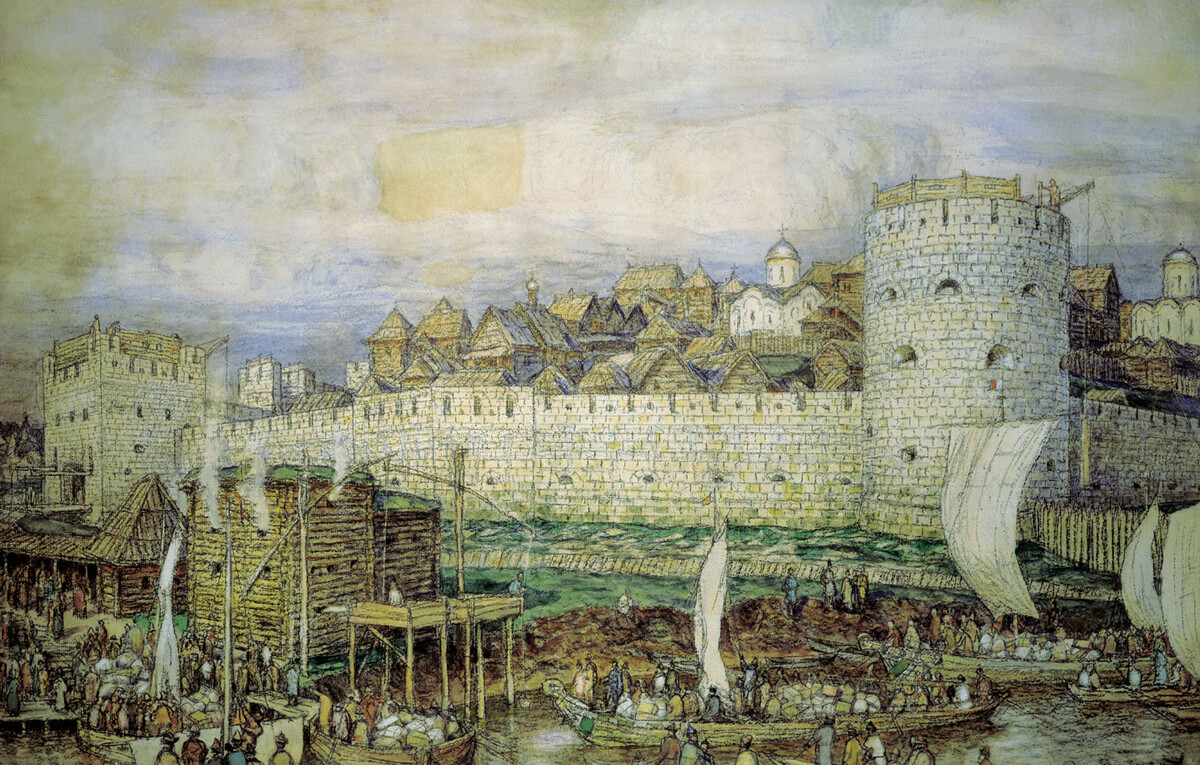

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Moscow Kremlin under Ivan Kalita”. 1921

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Moscow Kremlin under Ivan Kalita”. 1921

The walls of the city changed several times after this, but the wall of Ivan I Kalita proved to be the most reliable one, equipped with towers and constructed from thick oak logs. But even that wall couldn’t withstand fire – during the Vsesvyatsky fire of 1365, the Kremlin burned down, as well, after which the decision was made to build fortifications from stone.

White-stone Moscow

The first stone Kremlin, which replaced the wooden fortress, was built under Dmitry Donskoy – in 1366-1367. It was built from limestone – a white type of stone, of which they required more than 100,000 tons. Thanks to this new Kremlin, the entire city now had the name “white-stone Moscow”. Already back then, the length of the walls amounted to almost two kilometers, while the general perimeter of the fortress was very reminiscent of the plan of our contemporary Kremlin. The walls acquired eight or nine towers – mostly from the “field” side (meaning the side not facing the river).

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Probable view of the white-stone Kremlin of Dmitry Donskoy. The end of the 14th century”. 1922

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Probable view of the white-stone Kremlin of Dmitry Donskoy. The end of the 14th century”. 1922

For more than a hundred years of its existence, the wall deteriorated a lot – due to moisture, limestone easily crumbled and, from the middle of the 15 century onwards, the wall had to be repaired almost perpetually.

In 1485, Ivan III initiated the largest construction project of Russia at that time – as the prestige and the military significance of Moscow required. A new fortress emerged in place of the Kremlin of Dmitry Donskoy.

Ivan III’s Kremlin

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Moscow Kremlin under Ivan III”. 1921

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Moscow Kremlin under Ivan III”. 1921

By the order of Ivan III, the parts of the wall that had fallen into disrepair were torn down. The best Italian engineers were invited for the construction of the new Kremlin. In Muscovy, for convenience, they were all simply called ‘fryazi’ or ‘fryaziny’ – meaning ‘Italians’. As such, Milanese Pietro Antonio Solari became Pyotr Fryazin, Antonio Gislardi from Vicenza became Anton Fryazin, Marco Ruffo became Mark Fryazin and so on.

However, Ridolfo Fioravanti from Bologna was called ‘Aristotle’ in Moscow, which highlighted his exceptionalism and his great talent. He was invited to Moscow by Ivan III to erect the main cathedral of the Kremlin – the Dormition Cathedral. ‘Aristotle’ was the author of the technology of making the bricks, from which the wall and the towers of the Kremlin are built.

Ivan III and Italian architect Aristotle Fioravanti

Ivan III and Italian architect Aristotle Fioravanti

The new fortress was constructed gradually, not to leave the heart of Moscow unprotected. The old wall’s white rubble stone foundation (and, in some places, the remaining parts of Dmitry Donskoy’s wall) was deemed sound and it became part of the foundation of the new wall, as well.

The wall of Ivan III’s new grand fortress reached a length of approximately 2.25 kilometers. Its thickness, to this day, varies from 3.5 to 5.5 meters with a height of 5 to 19 meters. Ivan III’s wall boasted 18 towers, including gatehouses. The Kremlin’s new look stayed almost unchanged until the 17th century. Then, all the towers of the Kremlin, which are the symbol of Moscow today, were furnished with decorative spires and the majority of their embrasures were walled up. The number of towers also grew to 20.

The Kremlin also had three outposts (the so-called ‘barbicans’); only one of them has survived to our day, albeit seriously redone and rebuilt – the Kutafya Tower.

The Kutafya Tower

The Kutafya Tower

The walls of the Kremlin are lined with bricks only from the outside: on the inside, they are made from the remains of Dmitry Donskoy’s wall that were reinforced with lime mortar. Overall, 100 million bricks were used in the construction, which were a novelty for Russia at the time. The so-called ‘two-handed’ half-pood (an old Russian measure of weight) bricks that weighed up to 8-9 kilograms were used. They were called ‘two-handed’ bricks, because the workers had to lift them with both hands.

Gerard De La Barthe, “View onto Moscow from the Balcony of the Kremlin Palace in the Direction of the Moskvoretsky Bridge”. 1797

Gerard De La Barthe, “View onto Moscow from the Balcony of the Kremlin Palace in the Direction of the Moskvoretsky Bridge”. 1797

The Kremlin walls were not always red – from at least 1680 onwards, they were painted white with white lime. The paint was constantly renewed. Judging by surviving photos, the last time the Kremlin was painted white was approximately in the 1880s. Gradually, the white color faded, wore off and the Kremlin regained its initial, red-brick color.

The Kremlin had tremendous defensive potential for its time. From the inside, semicircular arches were made in its walls, which allowed embrasures to be placed on the bottom level, used by both cannons and firearms. At the same time, the walls retained their formidable thickness.

A battered face at the base of the wall (talus) protected it from siege towers, scaling ladders, and mining. From the top, the wall bristled with 1045 M-shaped merlons, which people called ‘swallow’s tail’. Their height reached 2.5 meters; the merlons were up to 70 centimeters thick. Every merlon required 600 bricks. During sieges, like in European fortresses, the crenels (spaces between merlons) were covered with wooden “shields”, while the wall itself was covered by wooden hoardings.

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Bookshop on the Spassky Bridge in the 17th century”. 1916

Apollinariy Vasnetsov, “Bookshop on the Spassky Bridge in the 17th century”. 1916

The fortress was also protected by a ditch – from the “field” side, on the territory that is currently occupied by the Red Square. It was called Aleviz’s Ditch after architect Aleviz ‘Novy’ (‘New’) Fryazin, who designed it. It existed until 1814, when it was filled with earth.

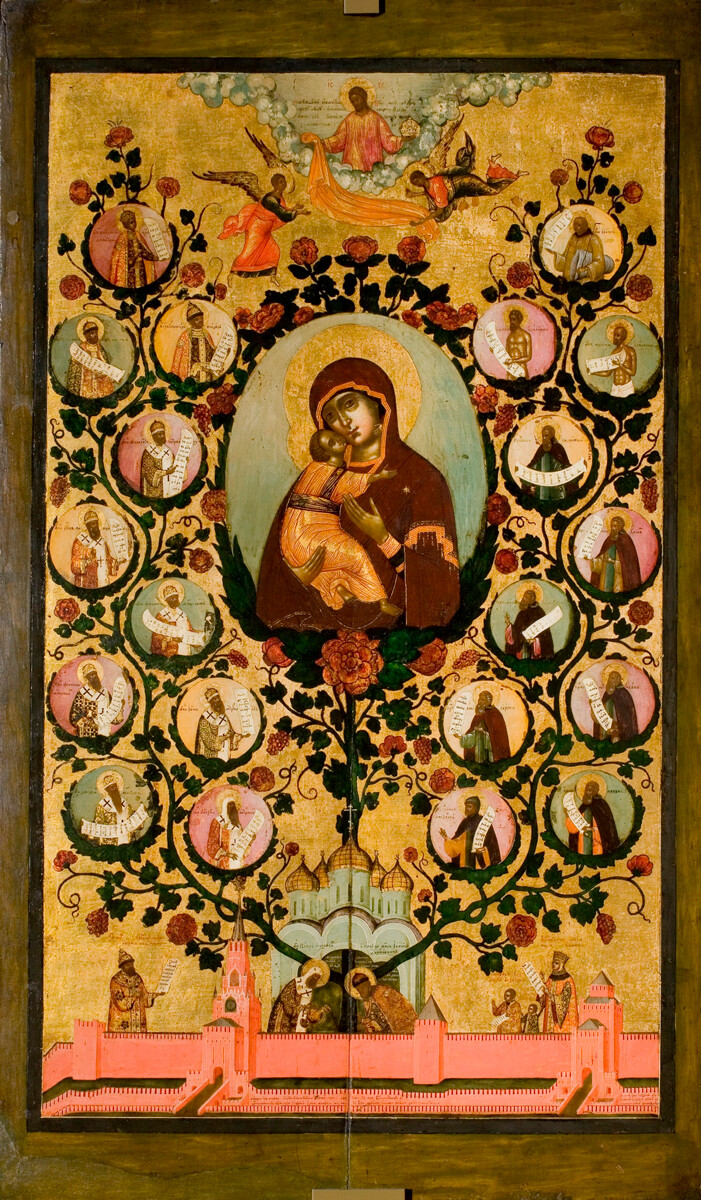

The Kremlin wall and its ditch depicted in the icon by Simon Ushakov, ‘The Tree of the Russian State. Praise of Our Lady of Vladimir’, 1668.

The Kremlin wall and its ditch depicted in the icon by Simon Ushakov, ‘The Tree of the Russian State. Praise of Our Lady of Vladimir’, 1668.

Tayniks – underground galleries that allowed the besieged defenders to access a source of drinking water, be it a well or an exit to a ditch filled with water, were often arranged in fortresses built in Rus’ and later.

But there were also tayniks that led beyond the fortress walls – for example, for a counteroffensive. The Kremlin has some of its own tayniks; during the construction of the Taynitskaya Tower, a hidden well and an exit to the Moskva River were arranged. There was also an underground gallery between the Nabatnaya Tower and the Konstantino-Leninskaya Tower with a cannonball cache.

During its existence, the Kremlin wall was damaged and repaired many times; it received especially significant damage in 1812 – repairs were finished only by 1822. In 1917, artillery shelled the wall and, during the Great Patriotic War, despite an elaborate camouflage, dozens of bombs hit the Kremlin.

Moscow Kremlin nowadays

Moscow Kremlin nowadays

The Kremlin – the creation of Italian engineers and Russian builders – has survived to our day in a very altered shape, losing its initial look. Nonetheless, different periods of Russian history have left their mark on the Kremlin and its famous wall, turning it into an invaluable monument.