5 facts about Empress Elizabeth, the last Romanova in the direct female line

December 6, 1741, at the head of the grenadiers of the Preobrazhensky Regiment, the daughter of Peter the Great made her way to the Winter Palace. Getting out of her sleigh on Admiralty Square, Elizabeth walked with difficulty in the deep snow. Then the Guards picked up the newly-crowned empress on their shoulders and carried her into the palace. Thus began her 20-year reign.

1. Like her father Peter, Elizabeth aspired to be a ‘European’

Elizabeth as a child, 1712-1713

Elizabeth as a child, 1712-1713

"Tsarevna Elizabeth speaks more German than Russian", – so wrote Peter the Great's sister and Elizabeth's aunt, Natalia Alexeevna, in 1713. Little Elizabeth, who started with her first German textbook at the age of three, by the age of four was speaking German to relatives, guests, and servants. By the age of twelve she knew French well, and by sixteen she spoke it like a native. Like her father, Elizabeth was very receptive to all things foreign and wanted to communicate with foreign ambassadors and guests herself.

Also, like her father, Elizabeth paid great attention to the development of public education in Russia. During her reign the charter and staff of the Academy of Sciences were reformed, and the Moscow University (1755) and the Imperial Academy of Arts (1757) were opened. A full-fledged reform of the entire Russian educational system, a report on which had already been prepared and discussed by the highest dignitaries and the Empress, was interrupted only by her death in 1761.

2. She sometimes had a rustic demeanor

Elizabeth (R) and her sister Anna (L), 1717

Elizabeth (R) and her sister Anna (L), 1717

In 1730, Elizabeth, who was then 21 years old, was supposed to inherit the throne after the death of Peter II, in accordance with her mother's will. But the throne was seized by Anna, her cousin. In the early 1730s, Elizabeth moved to Moscow, where she lived in the royal village of Pokrovskoye-Rubtsovo – near the current metro station Electrozavodskaya, on the bank of the Yauza River. There still stands a wooden palace that had been restored by her order in 1733. While Elizabeth spent time there, she socialized a lot with the palace peasants, even led them in round dances and sang songs.

Elizabeth's palace in Moscow

Elizabeth's palace in Moscow

In Moscow, she also became addicted to the rather strange, established habit among the local aristocracy – tickling or scratching the bottom of her feet at night before going to sleep. When Elizabeth became an empress, she was keen that her noble ladies-in-waiting would also tickle or scratch her heels, and they fought for this prestigious position.

In addition, according to the memories of contemporaries, Elizabeth was sentimental and pious, but at the same time she was prone to outbursts of anger. Historian Kazimir Waliszewski recalls such a legend: "Lopukhina (Natalia Feodorovna Lopukhina (1699-1763), a lady of state for Elizabeth), who was famous for her beauty, and therefore aroused the jealousy of the Empress, decided, for frivolity or in the form of bravado, to appear with a rose in her hair, at the same time when the Empress had a similar rose in her hair. In the midst of the ball Elizabeth forced the guilty one to kneel, demanded scissors, and then cut off the inappropriate rose along with a strand of hair to which it was attached, and, rolling the culprit two good slaps, continued to dance. When she was informed that the unfortunate Lopukhina had lost her senses, she shrugged her shoulders: ‘Fair enough, such a fool!’"

3. Elizabeth promised that no executions would take place during her reign

Elizabeth in the uniform of the Preobrazhensky guard regiment

Elizabeth in the uniform of the Preobrazhensky guard regiment

There is a legend that before going to the barracks of the Preobrazhensky Regiment upon her ascension to the throne, Elizabeth prayed and took an oath – if she ascended the throne, no death sentences would ever be passed under her rule. Formally, this was true, but this does not mean that the punishments of her era were merciful. In 1743, the same State Dame, Lopukhina, for participation in a conspiracy against the Empress was beaten with a whip, had her tongue pulled out and exiled to Siberia.

In addition, under Elizabeth the prison labor camp at Rogervick Bay was reopened. Those who should have been sentenced to death were exiled there. Laboring in such inhumane conditions, most convicts died in just a few months.

4. She loved dressing up and dressing people up

Elizabeth's coronation dress

Elizabeth's coronation dress

Like her father, Elizabeth was a trendsetter. She strictly monitored fashion at the imperial balls when noble ladies appeared each time in lavish new dresses, which resulted in the court being faced with huge expenses. But the Empress was not to be daunted. According to various estimates, she kept from 8,000 to 15,000 dresses, and her dressing room occupied a huge hall in the Winter Palace. After the Empress's death, all these dresses were donated to monasteries and churches.

A carriage given to Elizabeth by Friedrich II the Great

A carriage given to Elizabeth by Friedrich II the Great

From the time of her accession and until 1750 so-called "metamorphosis balls" became common at Elizabeth’s court, when the noble men appeared in ladies' suits, and the noble women in men's clothing. Elizabeth herself took on the personas of either a Dutch sailor, or a musketeer, or a Cossack. She also invented costumes for the troupe of her home theater, which she took a fancy to in the 1750s. In 1756, the troupe of Fyodor Volkov, which had received theatrical training under the supervision of Elizabeth herself, became known as Russia’s first official theater.

5. She was pious and made pilgrimages on foot

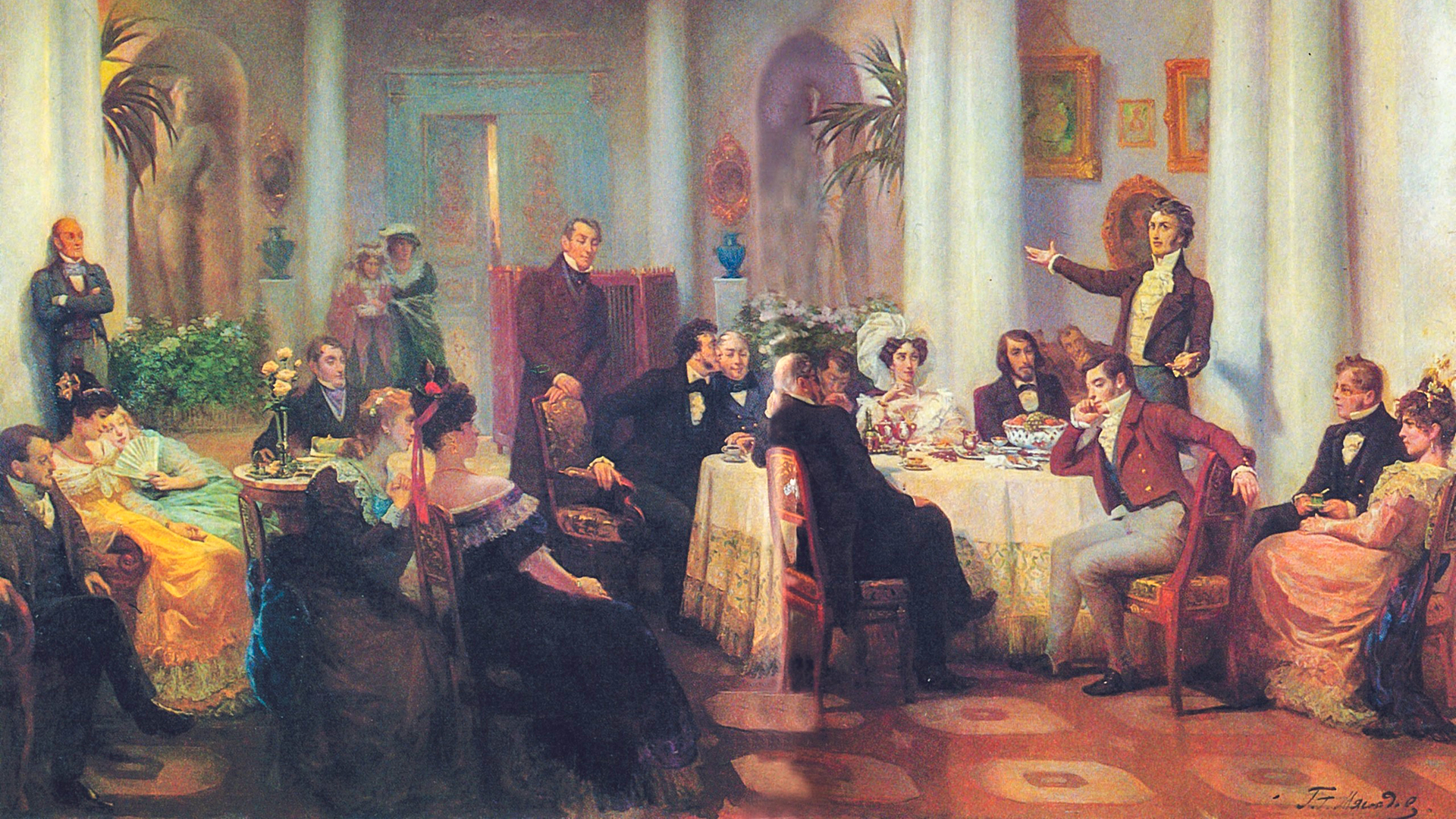

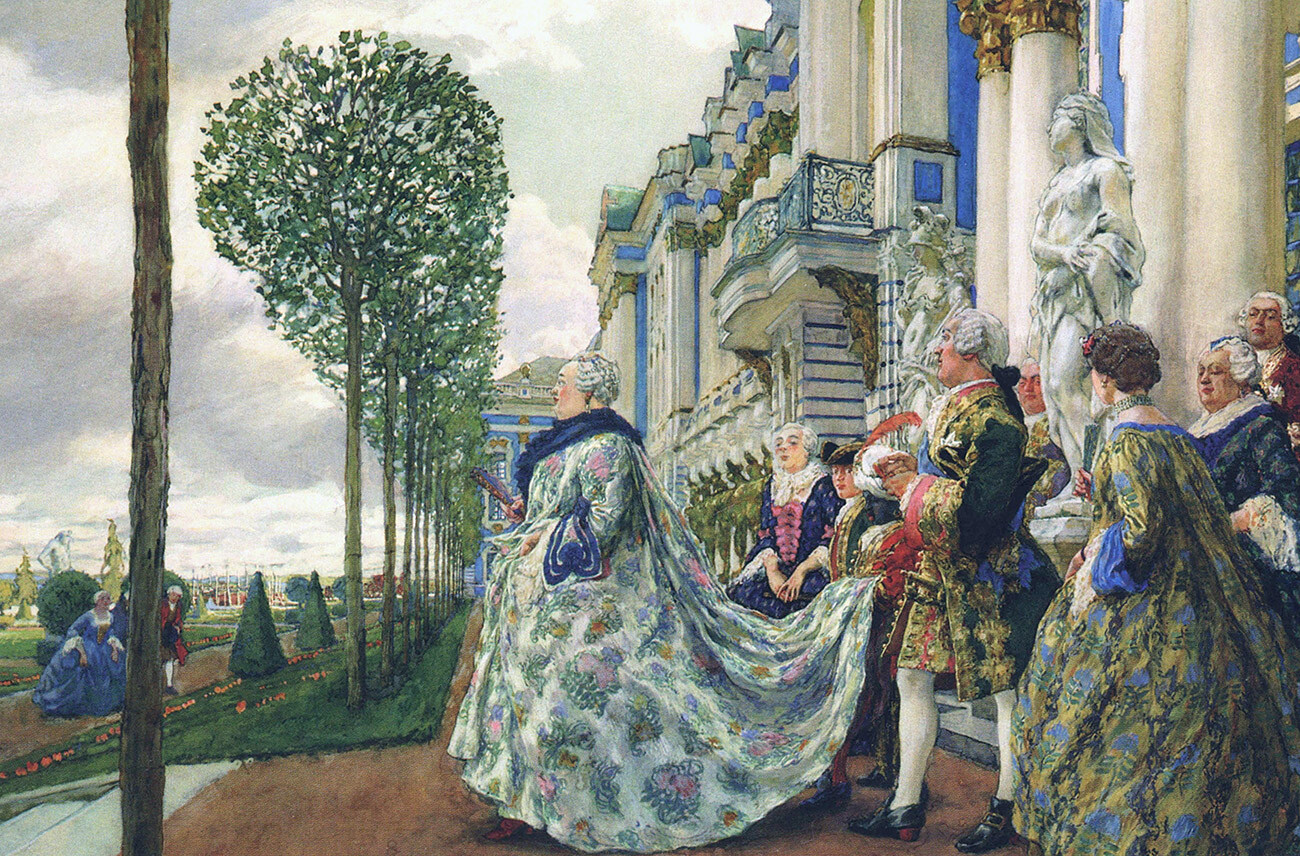

Elizabeth takes a walk in Tsarskoe Selo

Elizabeth takes a walk in Tsarskoe Selo

Elizabeth was characterized by deep and sincere religious piety. It is important to note that Elizabeth was the last true Romanov in the direct female line on the Russian throne. She was well aware of this, and considered it her duty to make pilgrimages to the medieval monasteries around Moscow – Savvino-Storozhevsky, New Jerusalem, and Trinity-St. Sergius Lavra.

Kazimir Waliszewski wrote: "Traveling on foot, she used to spend weeks and sometimes months to pass sixty miles separating the famous monastery from Moscow. It happened that, tired, she could not walk the last three or four kilometers to a place where she ordered houses to be built, and where she planned to rest. She then reached the place in a carriage, but the next day the carriage would take her back to the place where she had last taken a break on her walk".

Elizabeth was much engaged in the affairs of the church, and during her rule the translation of the Bible into the Russian vernacular, which had begun under her father, was completed. "Elizabeth's Bible" of 1751 is still used, though with minor changes, in the rituals and masses of the Russian Orthodox Church.