How Russians & the Chinese got rich and deceived each other over tea

Every year, starting from 1727, Russian and Chinese traders would go to Kyakhta on sledges and chariots, troikas and palanquins. They traveled great distances to make tea deals. At that time, Kyakhta was dubbed ‘Siberian Hamburg’ and ‘Venice of the desert’. Huge sums of money were being made there.

Russian merchants from a special committee were engaged in working out the terms of exchange, would agree with their Chinese counterparts on prices for the current season, viewed other merchants’ goods and offered their own. With the help of informants, they could vary the time of delivery of their products in order to get additionally rich.

Kyakhta, 1783. By Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse.

Kyakhta, 1783. By Louis Nicolas de Lespinasse.

Goods for sale, i.e. to exchange for tea, were brought from all provinces along the Siberian tract, which was also called the ‘Great Tea Route’. It ran from Moscow to Kyakhta. From there, tea traders crossed the steppes of Inner Mongolia and arrived in Kalgan, a major outpost on the Great Wall of China, considered the gateway to China.

According to the decree of Emperor Paul I ‘On the Kyakhta Tariff’ of March 1800, all settlements were made by barter. Merchants exchanged goods produced in Russia for Chinese teas until 1855, when the government finally allowed monetary settlement. Textiles and leather, bread, goat skins, morocco, yuft, saiga and mule deer horns were used. By the way, fur of fur-bearing animals, such as foxes, otters, ottershoes, ermine, lynxes and even cats, was especially popular among the Chinese.

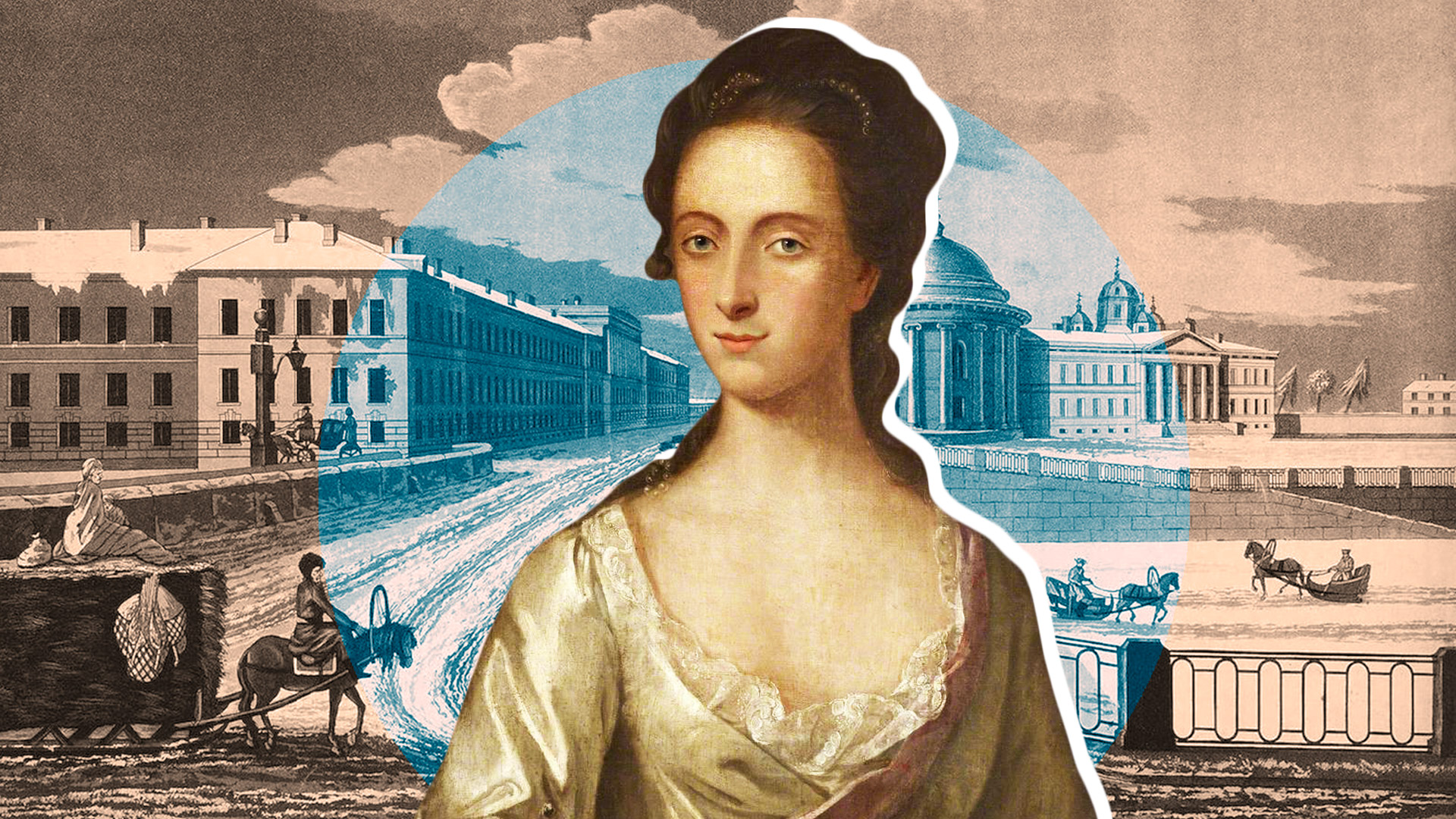

1851 map, the route from Irkutsk to Beijing, on the border of the states twin cities - Kyakhta and Maimachen.

1851 map, the route from Irkutsk to Beijing, on the border of the states twin cities - Kyakhta and Maimachen.

All goods in Kyakhta differed in the way of delivery and storage period and different time slots had to be set aside for their arrival. Thus, fur from the Yakutsk fair arrived in November and Moscow leather and fabrics – in the first months of the new year.

Trade in Kyakhta was somewhat similar to the stock market on modern stock exchanges. Kyakhta “bulls” bet on the upside and made purchases of tea or furs in advance and then sold them at the peak of demand. “Bears” played down and deliberately did not cause demand, waiting for more favorable conditions.

Once on the "bear" market, the so-called Shestov brothers managed to make a big profit. In 1841, the Chinese delivered a large shipment of tea to Kyakhta later than usual, because of the difficult mountain roads. As a result, they were allowed to sell only first-grade family tea, in order not to waste time on checking cheap tea (because counterfeiting also occurred at times). And while the middle-level merchants pondered whether to buy expensive goods, the Shestov brothers, who had information about the situation, had already managed to buy a considerable amount of tea and, with it, became situational monopolists.

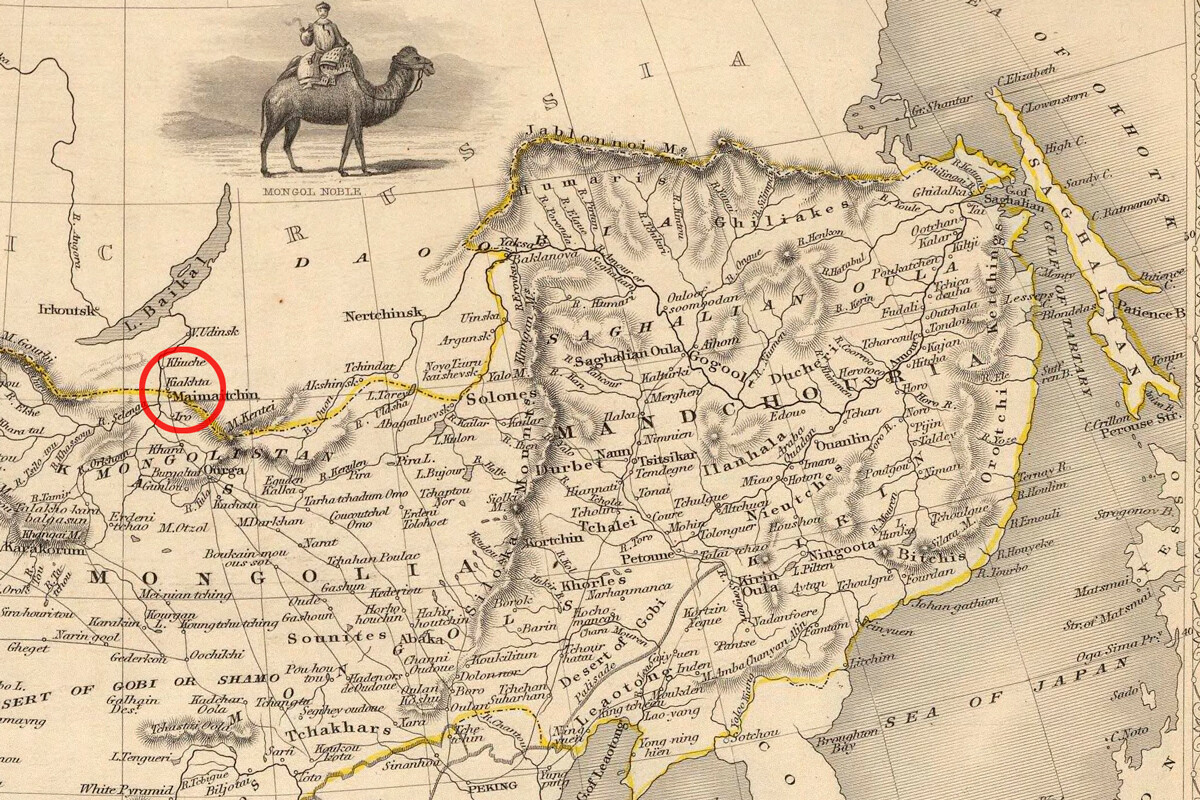

Russian and Chinese caravans in Kyakhta.

Russian and Chinese caravans in Kyakhta.

When traders were threatened by an oversupply of tea inside the country, Russian merchants on the contrary suspended purchases, fearing to drop prices at the fair and in Moscow. To do this, they delayed the arrival of their goods, without which it was impossible to complete a transaction.

However, this did not work for long. Furs had to be sold in the fall or early winter – later, the skins lost their marketable appearance and demand for them in China dropped with the arrival of the warm season. Also, by spring, logistics within Russia became more expensive – transportation of goods to domestic fairs in winter time was twice as cheap. This was explained by the danger of thawing, rivers overflowing their banks, high risks of spoilage of goods, expensive hiring of a coachman and lack of livestock fodder.

Kyakhta in 1880.

Kyakhta in 1880.

Chinese tea traders also came to Kyakhta in advance. But, not only because they wanted to make deals as early as possible. They were instructed to do so by a secret instruction on trade conspiracy. The Russians called it the ‘Chinese rascal’s charter’.

According to the ‘Instruction of Lifanyuan, adopted by the Chamber of Affairs of Vassal Territories’, upon arrival in Kyakhta, residents of China were supposed to learn about the Russian need for goods, the price of sales, to cause an artificial increase in the cost of increased supply of Russian products – and then suddenly drop prices. The statute recommended calling Russian merchants to feasts, giving them presents and learning commercial secrets on a friendly foot. There was even a punishment for violating this instruction. That's the kind of legalized industrial espionage and insider trading that was going on.

The main drink

The profitability of the tea enterprise depended more on high pricing within the empire, rather than on profitable international trade. The average customer bought tea three to ten times higher than the original price.

A merchant's family in the XVII century, 1896, Andrei Ryabushkin.

A merchant's family in the XVII century, 1896, Andrei Ryabushkin.

Despite this, according to information from the thesis of candidate of historical sciences Ivan Sokolov, tea sales in the Russian Empire did not fall, although in Russia the drink was first called "empty" and it was difficult to imagine that it would become more popular than kvas.

Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin wrote in ‘Gubernskie sketches’:

“After all, it seems that tea is a useless drink!” remarks Ivan Onufrich complacently. “But, if China won't give it to us, it can make a great fuss!”

Back in the year 1638, "an ambassador, boyar son of Vasily Starkov, was sent to Mongol Altyn Khan, who, on his return to Moscow, brought tea to Russia for the first time, among the khan's gifts to Tsar Mikhail Fedorovich". This is reported in the ‘Chronological list of the most important data from the history of Siberia’, published at the end of the 20th century in Irkutsk. Although the ambassador saw how tea was drunk in the bet at court ceremonies, he considered it an unsuitable commodity. Nevertheless, the tsar and his cronies liked the drink and next ruler Alexei Mikhailovich was even treated with tea. At the end of the 17th century, tea began to be sold in stores.

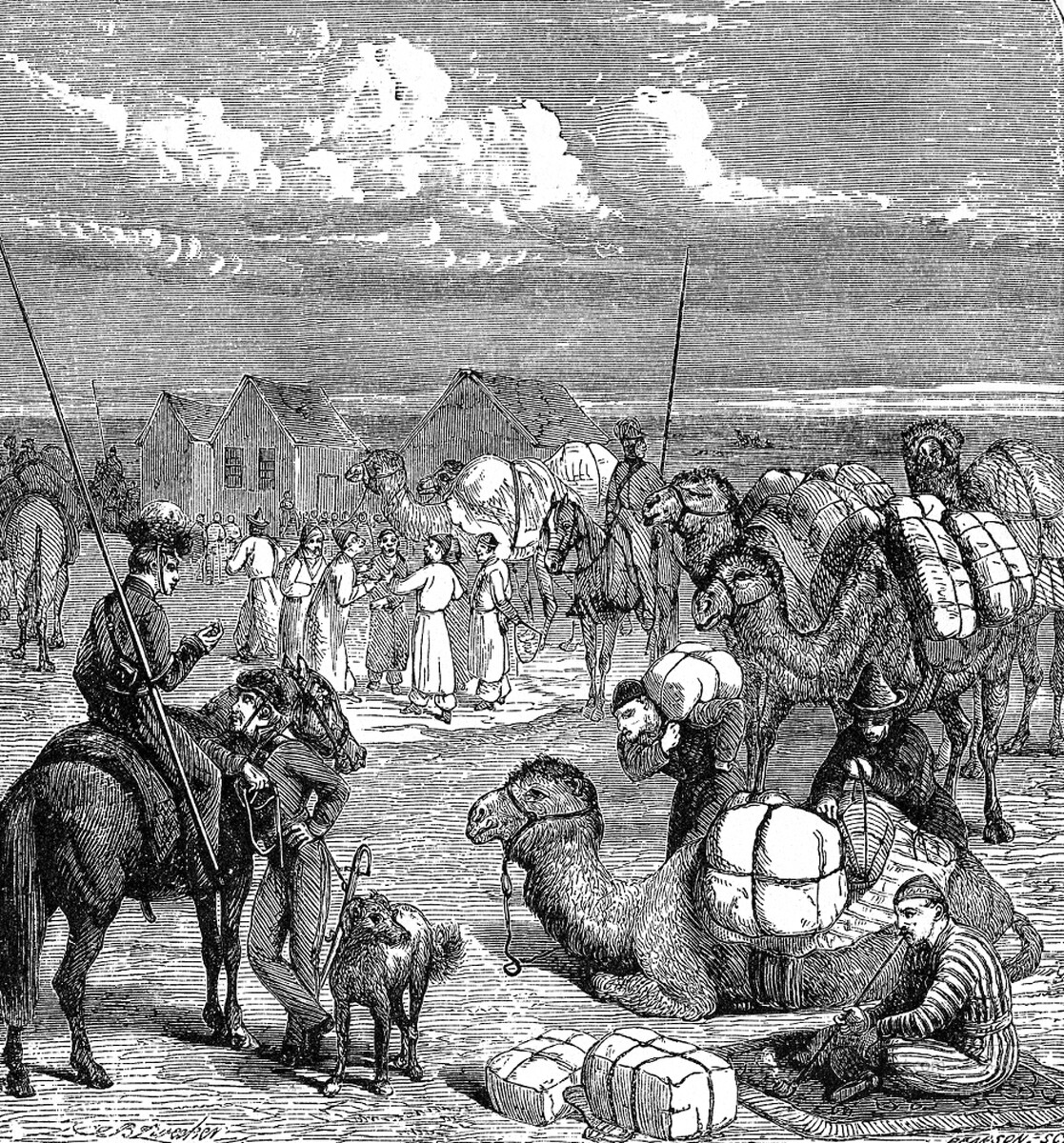

A tea caravan from China on the great post road in Siberia, Russia, engraving from The Illustrated London News, No 2731, August 22, 1891.

A tea caravan from China on the great post road in Siberia, Russia, engraving from The Illustrated London News, No 2731, August 22, 1891.

In the mid-19th century, tea became the main commodity of Russian imports. According to Nikolai Lyubimov, an employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, “tea has swallowed up all other Chinese items,” including manufactures. “Silk fabrics have already run out; ‘kitayka’ [a cloth with a touch of paper - ed.] is also almost running out and tea, tea will remain,” wrote the great Russian reformer Mikhail Speransky. He cared a lot about supporting the trade in Kyakhta and favored Russian merchants, so he kept an eye on the situation in the market.

At tea, 1914, Konstantin Makovsky.

At tea, 1914, Konstantin Makovsky.

The volume of sales grew every year. Karl Marx, on the front page of the New York Daily Tribune in 1857, stated: “Previously, the average annual volume of tea sales in Kyakhta did not exceed 100,000 cases per year, but, by 1852, it had already reached 1,750,000 cases and the total price of goods exceeded 15,000,000 American dollars.”

Tea resellers

The merchants themselves very rarely purchased tea. They entrusted the transactions to commission agents who permanently resided in Kyakhta. These people bought industrial goods in the European part of Russia with loans or the capital of their patrons, transported them to Kyakhta, exchanged them for Chinese tea and delivered it by land to Russian fairs or through Siberia to Europe. After selling it, they paid the debt to creditors and reported to the merchants.

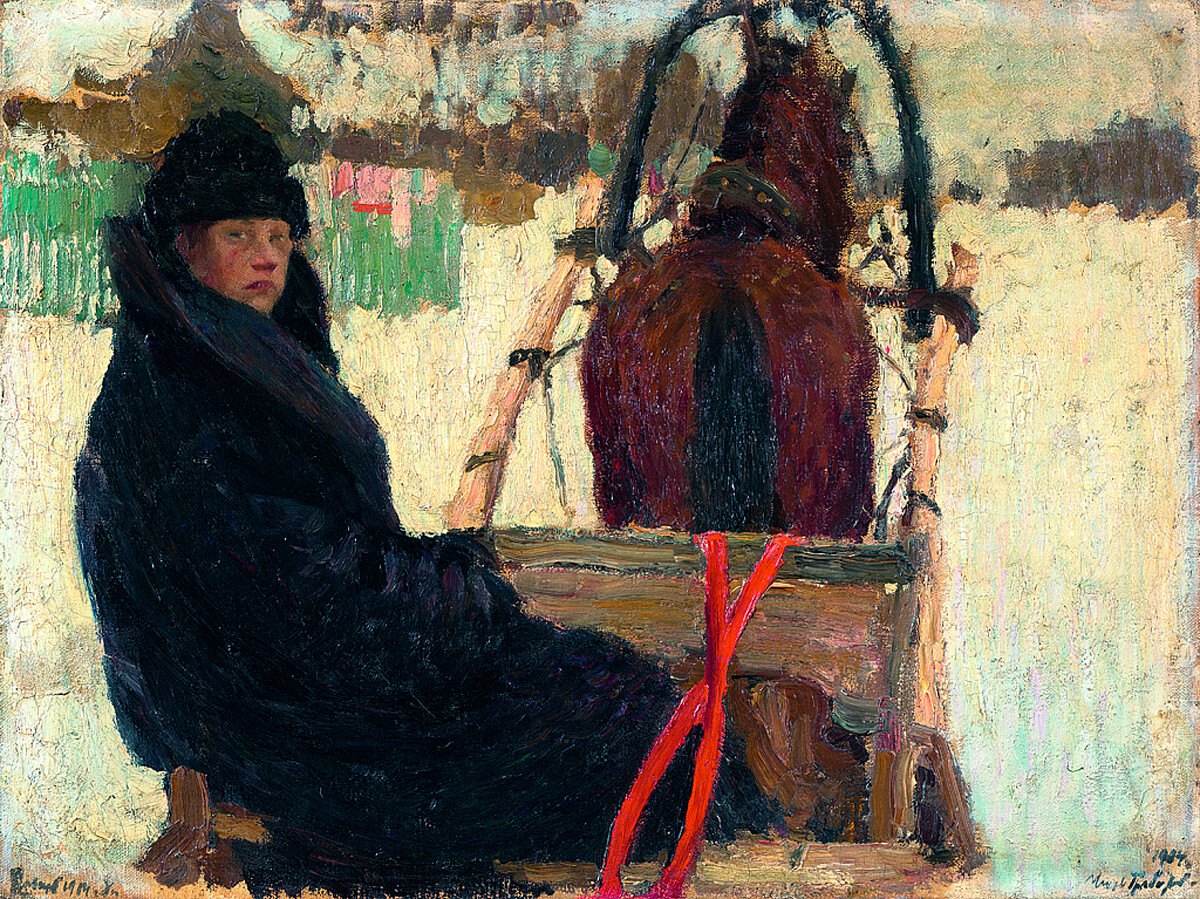

The Coachman, 1904, Igor Grabar.

The Coachman, 1904, Igor Grabar.

Russian ethnographer and economist Pavel Nebolsin noted: “…it may be that the trusted person dropped the owner's credit, it may be that he extracted a ruble for a ruble, but he is not required to produce any books or notes and is taken at his word.” There were frequent cases when commission agents sold the goods of Russian merchants for nothing, receiving bribes from the Chinese, or did not bargain at all. But, the damage done to their budget by their proxies was of little concern to the tea magnates for two reasons.

Alekseich. 1884. Konstantin Makovsky.

Alekseich. 1884. Konstantin Makovsky.

Firstly, the demand for tea was only growing and the profit covered both the interest to the middleman and the unprofitable exchange and logistics costs. And even lavish feasts, such as those organized by merchants selling Kyakhta goods at the Makaryevskaya Fair in Nizhny Novgorod: “…as the highest aristocracy of the Makaryevskaya Fair, they dine no other way than at 5-6 o’clock at the fashionable Nikita's, where all foreigners (mostly Germans and residents of St. Petersburg) gather and dine no other way than with champagne and truffles…”

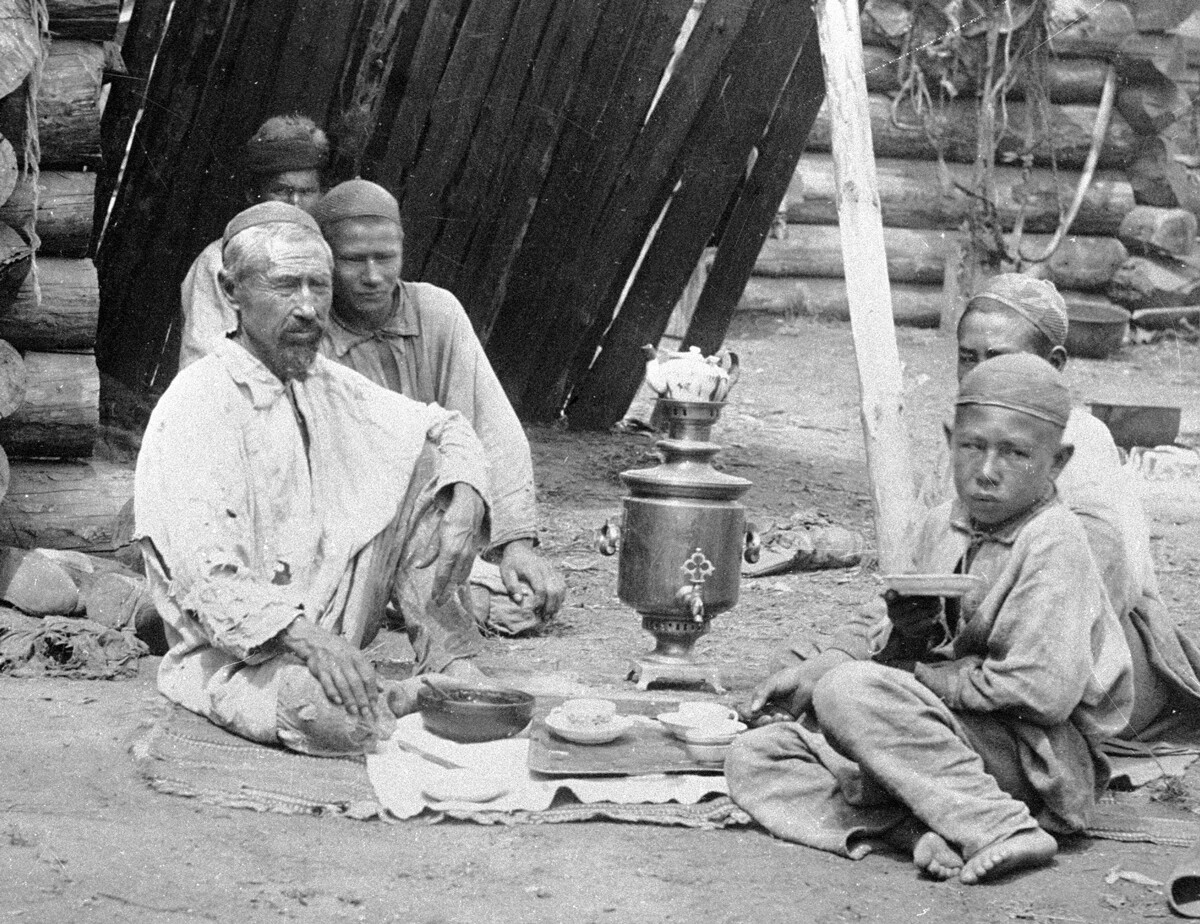

The Bashkirs drinking tea in the yard, 1914.

The Bashkirs drinking tea in the yard, 1914.

Secondly, the path to Kyakhta and back was full of dangers and a comparatively small loss was much better than death for a merchant. On the road, merchants could be attacked by robbers… or by their own companions. For example, in 1802, while passing through Tomsk province, an “attorney”, for the sake of enrichment, killed his employer and their coachman with an ax and tried to shift the blame on robbers.

From 1862, tea was imported to Russia by sea, as the Chinese opened seaports and the Suez Canal. Besides, it was much more profitable to deliver the goods through Odessa, bypassing Asia. And, with it, the exchange of tea in Kyakhta was halved. The customs office was transferred to Irkutsk and Kyakhta officials and merchants began to leave the city.

Tea traders traveled from Kyakhta to conquer and settle new cities, but they inadvertently spread the habit of tea drinking throughout Russia. The love for tea has not died out since then and lives on in every Russian home to this day.

Residents and guests of the Abramtsevo estate drinking tea in the garden.

Residents and guests of the Abramtsevo estate drinking tea in the garden.