What Russia learned from its biggest enemy

In the 13th century, the disparate Russian principalities were attacked and subjugated by the largest single state in the history of humankind, covering 24-33 million square kilometers. This was the Mongol Empire, created by Genghis Khan (1165-1227) and his descendants.

The Mongol invasion was a veritable nightmare for the Russian principalities. Russian foot soldiers, poorly versed in the art of war, and cities with wooden fortifications were crushed by the most formidable fighting force in the world at the time, which included light and heavy cavalry, archers, heavily armed infantry and siege machines.

The Mongol army in a traveling formation. A contemporary reconstruction

The Mongol army in a traveling formation. A contemporary reconstruction

Not long after the conquest of Russia, the Mongol Empire broke up into separate khanates; one of these, the Golden Horde, took control over the Russian lands. The Mongols did not want to conquer them entirely, merely collect tributes, so the Russian princes were forced to travel to the capital of the Golden Horde at Sarai (close to modern-day Volgograd) to receive yarlyks (edicts; another Tatar word which in modern Russian means “label”). These were official documents confirming the princes’ right to govern their own lands. This intolerable humiliation for such proud Russian warriors was the first step towards the formation of a single Russian state.

The Russians realized that the Mongol yoke could only be thrown off by adopting their oppressors’ tactics, both administrative and military. In 1380, at the Battle of Kulikovo, the Russian princes defeated a Golden Horde army for the very first time. Then a century later, Grand Prince Ivan III of Moscow defended the integrity of the state that he had created by facing down the Mongols in what became known as the Great Stand on the Ugra River. After this, the dependence of the Russian lands on the remnants of the Horde became largely formal.

“Moscow owes its greatness to the khans,” wrote the famous Russian historian Nikolai Karamzin. All subsequent military and political successes of the Moscow state on the international stage were largely a consequence of the involuntary ‘training’ that the Russians underwent while under the dominion of the Horde.

We list the most important things and concepts that the Russians borrowed from the Mongol-Tatars.

Military organization, the word bogatyr, battle cries

A Mongol war commander. A still from the "Mongol" movie, 2007

A Mongol war commander. A still from the "Mongol" movie, 2007

Despite their inferior numbers, the Russian infantry squads were strong and fearless in defending their native land. The offensive and defensive skills of the Russians were known throughout Europe. But heavily armed combatants were few in number. Although able to repel short raids and protect cities against sporadic attacks, when it came to facing the disciplined Mongolian army in the open field, the Russian forces – armed with pikes and axes – were overwhelmed. But even that was not the main reason for their defeat.

The Russians lost to the Mongols because they were divided. The princes and their druzhiny (royal troops) were not only scattered geographically – they had no idea how to negotiate with each other. Social and military issues in Ancient Russia were resolved at the veche, or popular assembly. For decisive action, this method was very slow and ineffective. In the first major battle against the Mongols on the Kalka River, the Russian princes could not agree on a coordinated strategy and were utterly routed.

Moreover, it was the Russian tradition for a prince to lead his troops into battle. Today it seems absurd, but the prince would head the charge against the enemy, increasing the likelihood of him being cut down early on. Soldiers deprived of their leader quickly became demoralized.

The battle on the Kalka river, 1223. A later reconstruction image

The battle on the Kalka river, 1223. A later reconstruction image

The Mongols operated differently. The khans themselves, as a rule, did not show up for battle, while their military leaders and generals observed the action from an elevated position, guiding their forces using flags, smoke and light signals, and trumpets and drums. In the event of a setback, it was the generals, not rank-and-file soldiers, who bore the responsibility.

To stand any chance at all, the Russians had to learn from the Mongols, starting with the very basics. For example, the Russian battle cry “Hurrah!” was, according to one theory, copied either from the Mongolian uragshaa (forward) or the Tatar ura (attack). Initially, a Turkic word bogatyr, so popular in Russia and meaning 'hero', means “brave.” Before the Mongol invasion, such people in Russia were called horobor (good in fighting) or udalets (a brave one).

As a result, the Russian victory in the Battle of Kulikovo over the Golden Horde commander Mamai was achieved by having a clear command center and an ambush regiment of heavy cavalry, which struck the Mongols not randomly but on command. By the way, the Russian cavalry combat techniques were also borrowed from the invaders.

Cavalry

A Mongol cavalryman. A still from the "Golden Horde" movie, 2018

A Mongol cavalryman. A still from the "Golden Horde" movie, 2018

Before the Mongol rule, horses in Russia were luxury possessions. Young princes were ceremonially put on horseback at the age of three, following the ancient Indo-European tradition of initiating noble offspring in the art of horsemanship. But after the Mongol riders demonstrated their superiority on the battlefield, the conquered Russians realized that they needed cavalry units of their own. Lone princes on horseback, weighed down by chain armor, were sitting ducks for the Mongol-Tatar mounted archers.

In the 13th–15th centuries, professionally trained cavalrymen began to appear in the Russian lands. Descended from the druzhiny, they came from noble and wealthy families, who were the only ones who could afford the horses and special attire required for cavalryman status.

Clothing

'Metropolitan Philipp condemns Ivan the Terrible,' 1800, by Yakov Turlygin

'Metropolitan Philipp condemns Ivan the Terrible,' 1800, by Yakov Turlygin

Before the Mongol conquest, men from the various tribes that inhabited the Russian lands tended to wear loose trousers and a shirt girdled at the waist by a fabric or leather belt. Outerwear consisted of a cape or cloak tied with strings. Status was demonstrated by the belt decoration, the cost of the cloak fabric, and its coloring (deep blue indigo was considered the most “expensive” color).

For fast horse-riding, especially in combat, such clothes were not very suitable – a fluttering cloak could get wrapped around the rider’s head, impeding visibility. So the kaftan was borrowed from the Mongols. This was a thick two-layered outerwear garment fastened with hooks. It could be done up at the top to keep warm and left unfastened at the bottom to make it easier to sit in the saddle, without it blowing around in the wind.

'Prince Alexander Nevsky begging Batu Khan for mercy for Russia,' a 19th-century image

'Prince Alexander Nevsky begging Batu Khan for mercy for Russia,' a 19th-century image

Many other items of clothing were adopted from the Tatar tribes that lived in the various khanates – the remnants of the Golden Horde. These people not only fought the Russians but also traded with them. As the Russians started wearing the new clothes, the Tatar names for them took root in the Russian language: kolpak (cap), kushak (sash), shtany (trousers), bashmak (boot), kumach (red calico), zipun (a homespun collarless coat), and many others. There were more exotic borrowings too. The Tatars made sheep and goat skins in a special way, from which the Russians acquired morocco leather, a new and luxurious material for them at the time. The Russians also adopted the custom of wearing a tafya, a type of skullcap worn by Tatar nobles.

One famous tafya wearer was Ivan the Terrible, who shaved his head bald in the manner of the Tatar khans. In general, the official and everyday vestments of the Russian tsars, their ceremonial coats, and kaftans decorated with gold and precious stones, which we see in portraits of the first Romanovs, were created with an eye on the garments of the Mongol and Tatar rulers.

Staging posts

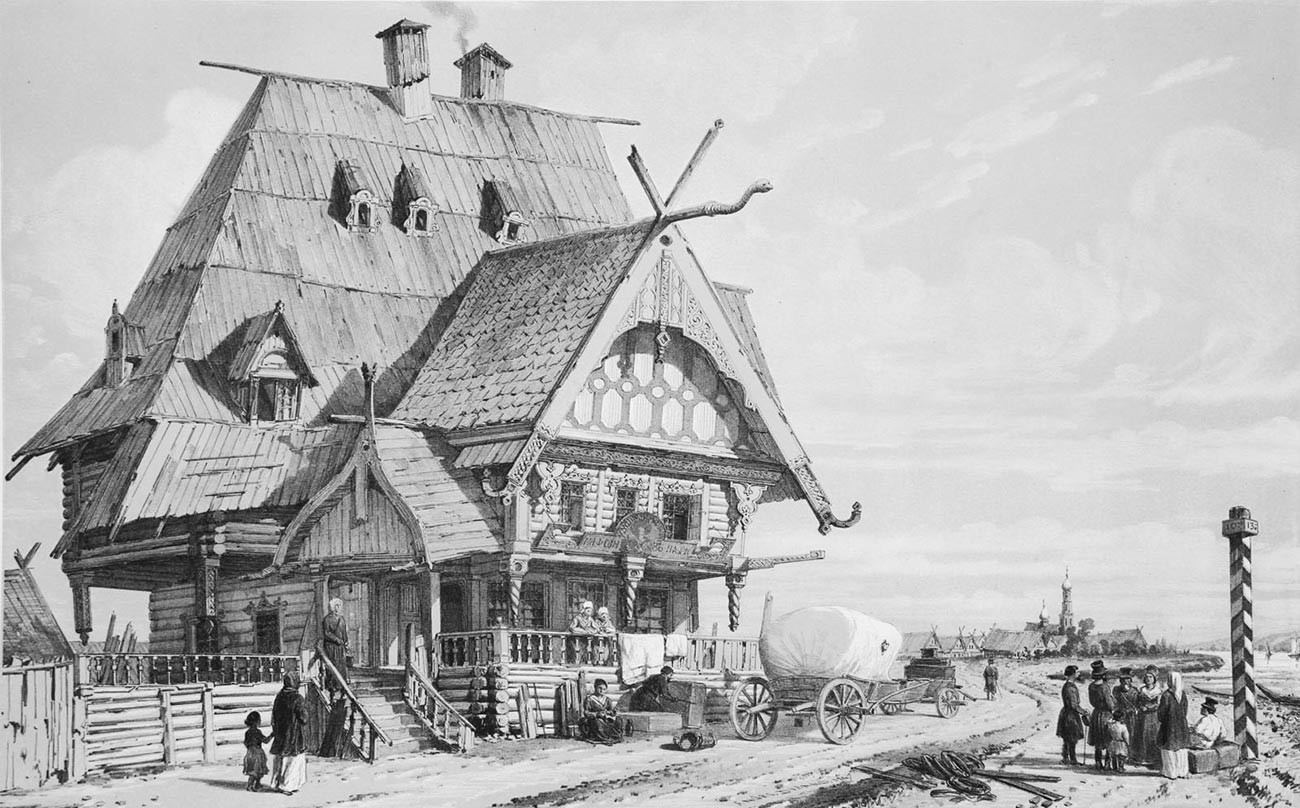

A post station on the Moscow-Yaroslavl road, 1839, by Andre Durand (1807-1867)

A post station on the Moscow-Yaroslavl road, 1839, by Andre Durand (1807-1867)

To manage their gigantic territory, Genghis Khan (or his descendants) created a network of stations (called yams) where messengers and couriers could spend the night and get a fresh horse. Mongol warriors were literally raised in the saddle – adults were trained to ride more than 48 hours on horseback without a break. After the subjugation of the Russian lands, staging posts were set up across the territory. The local population was obliged to keep stationmasters on duty, repair carts, and supply fresh horses. The word yamschik in the Russian language, meaning “coachman”, comes from this period.

The staging post service remained in Russia in various forms until the beginning of the 18th century. The Mongol-introduced system also helped solve the problem of governing a state of such enormous size and became one of the pillars of the Russian form of government, which was likewise adopted from the Mongol-Tatars.

State administration

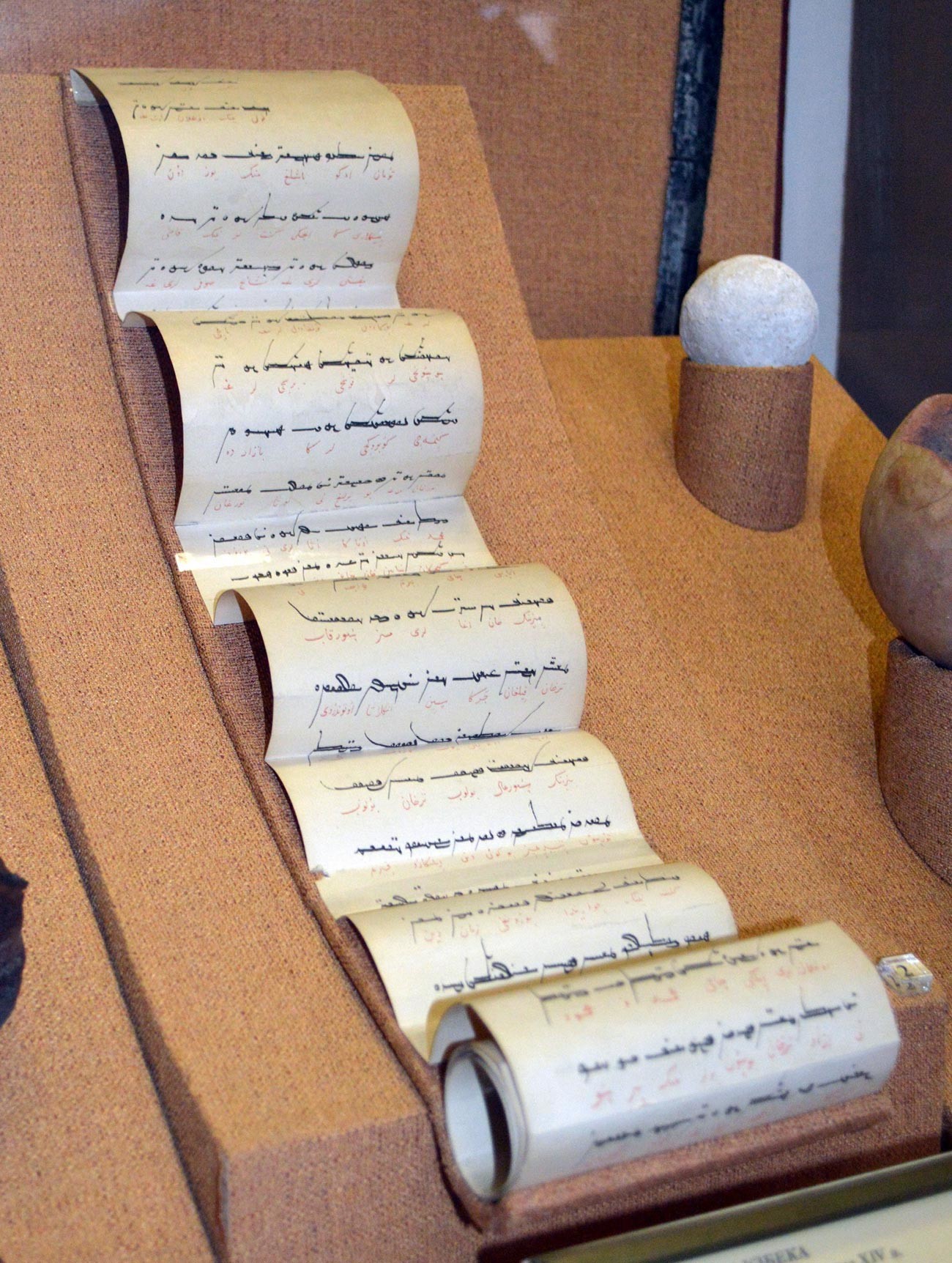

A typical Mongol jarlik dating back to 1397

A typical Mongol jarlik dating back to 1397

The Mongol-Tatar invasion put an end to the above-mentioned veche. It served the Mongols’ interests for Russia to continue to be ruled by sole, essentially puppet princes. The Mongols skillfully played the princes off against each other, which bars any talk of a natural fragmentation of the Russian lands, since they were forcibly prevented from uniting. Only after several decades did the princes come to understand what was happening, and begin to unite the lands around one center, which eventually became Moscow.

The mechanics of government were also taken from the Mongols: official documents confirming the rights of princes and monasteries to rule over the lands and peasants; the monetary and customs system (the Russian word dengi (money) comes from Turkic tenge (coin), and tamozhnya (customs) from Turkic damya (seal)); the inheritance of power; the centralized inventory of troops and military leaders; civil and military administration. In short, the influence of Mongol-Tatar practices on the Russian system of power was all-embracing.

Chiefly, however, whereas before the Mongol invasion the Russian lands had been governed by a multitude of princes who resolved issues collectively, by 1480 – the year of the Great Stand on the Ugra River – Russia had a sole and undisputed sovereign in the shape of the Grand Prince of Moscow, at that time Ivan III the Great. It saved Russia and marked the start of a new era in its history.