The Russian Revolution was not actually led by Lenin. But by whom then?

Leon Trotsky was one of the most dedicated advocates of the Russian Revolution. He had to go through a lot - exiles and arrests, a tough competition within the party ranks and lofty positions, but, in the end, also expulsion, death and oblivion.

The best Bolshevik

Trotsky took part in revolutionary activities at an early age. At the age of 17 (in 1896), he was already a member of a revolutionary unit spreading propaganda among workers. This was followed by two years in jail, an exile to Siberia and a stint abroad. In 1902, in London, Trotsky met Lenin and other prominent revolutionaries. Later on, his party colleague Lunacharsky, recalled: “Trotsky virtually struck the foreign public with his eloquence, education, which was remarkable for a young man, and self-confidence… Because of his young age, he wasn’t treated seriously, but everybody gave credit to his outstanding public speaking skills, certainly feeling that he was not a chick, but rather an eaglet.”

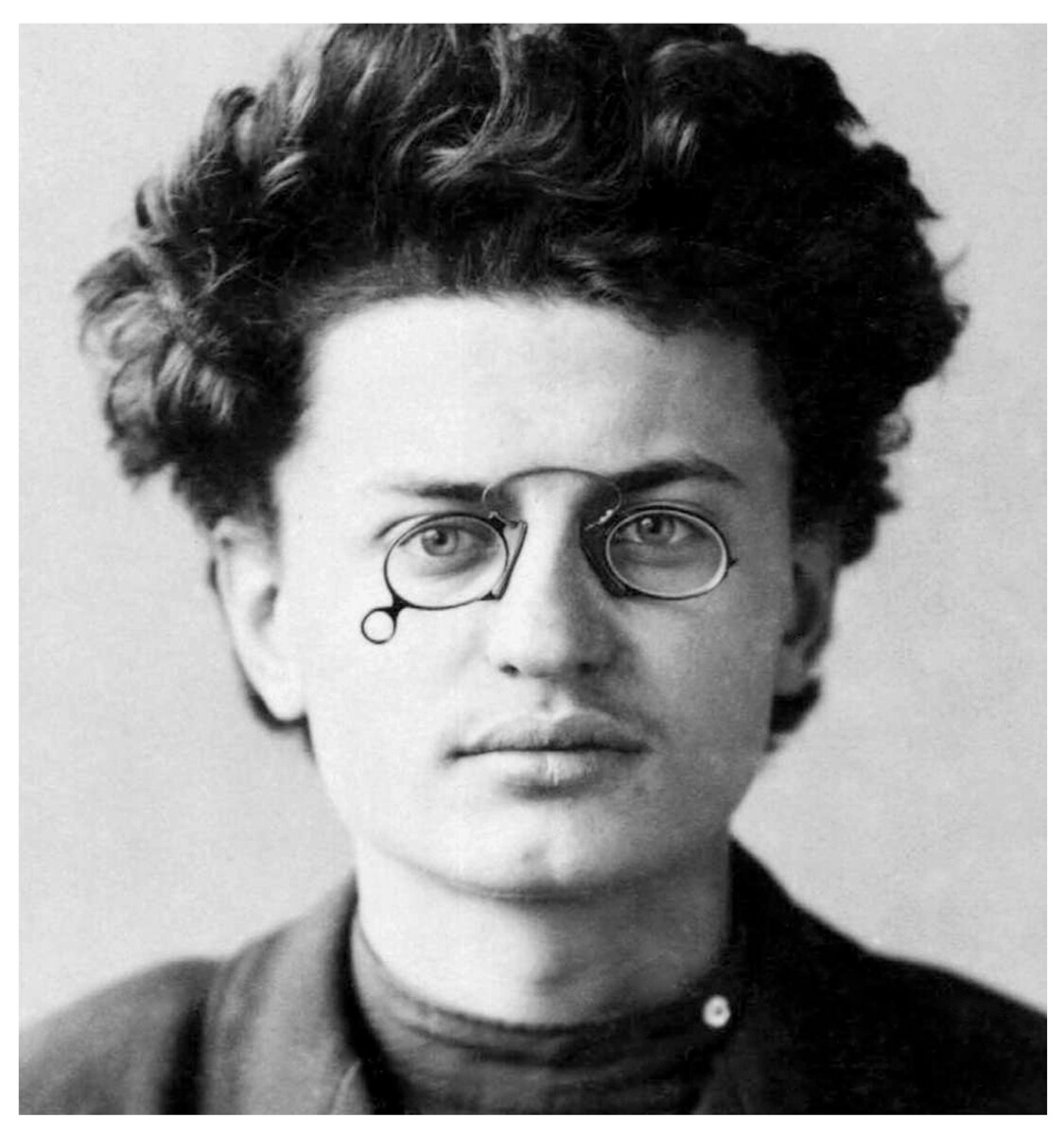

Young Leon Trotsky.

Young Leon Trotsky.

Later on, Trotsky used his unrivaled eloquence for the benefit of the revolution: he actively wrote for such revolutionary newspapers as ‘Iskra’ and ‘Pravda’, as well as engaging in oral propaganda. His flowery speeches were cited and written down. Subsequently, during the revolution, it was Trotsky who managed to win over the remaining hesitating military units to the Bolshevik side.

Lenin’s influence and authority virtually prevented the growth of Trotsky’s popularity. He was dubbed Lenin’s “baton”, hinting at the fact that the former was just doing as Lenin pleased. Yet, as time passed, Trotsky earned his party colleagues’ respect, boosting his authority and even starting to criticize Lenin.

Leader of the armed coup d'état

Due to the myths created by the Soviet authorities, the mentioning of the October Revolution typically invokes the image of Lenin in an armored vehicle. Yet, at the time it happened, Lenin was far away from Russia. He was staying abroad and took part in decision making from there, while not actually leading it in the proper sense of the word. It was Trotsky who did it. On October 9, 1917 (under the Julian calendar), he initiated the creation of the Military Revolutionary Committee, which became the driving force of the coup.

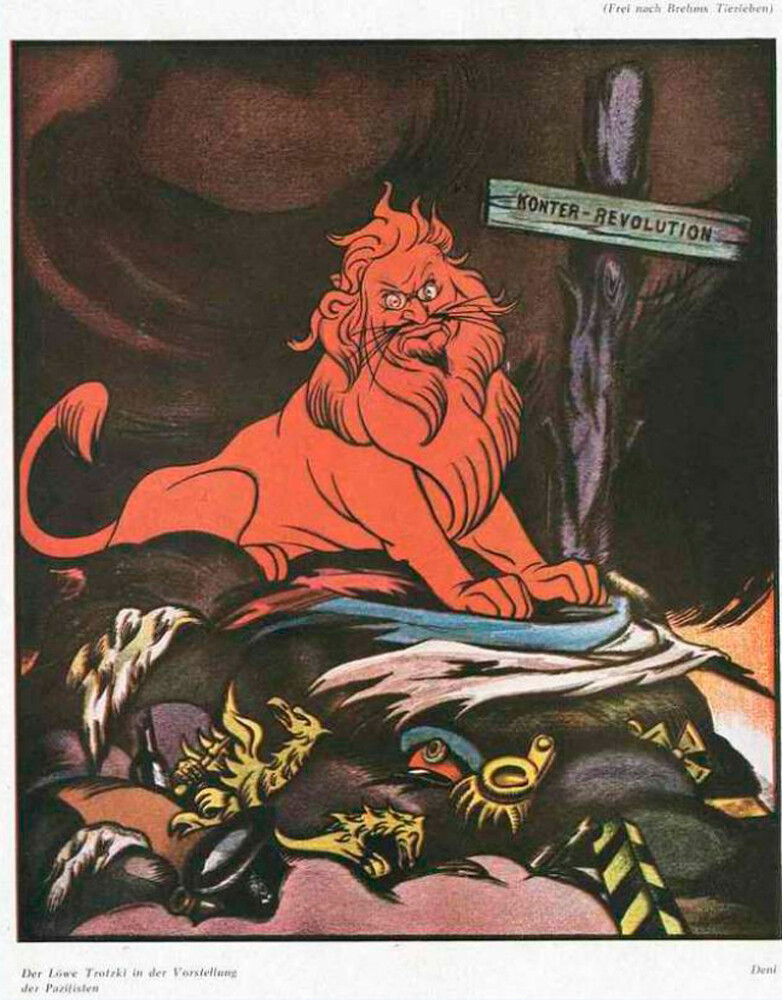

Leon Trotsky standing on the grave of counter-revolution.

Leon Trotsky standing on the grave of counter-revolution.

The committee was to unite all the revolutionary forces to stage the military coup, provide all the military units with weapons and manage the operation of seizing power in the capital. To make it happen, the Military Revolutionary Committee had to gain the support of the Petrograd garrison - the main military unit in the capital. Thanks to Trotsky’s power of persuasion, the garrison ultimately joined the revolutionaries. Under his command, it was supposed to take control of post offices, railway stations, the State Bank, telephone stations and other strategic places, including the Winter Palace, where the provisional government was based. On October 25 (November 7, under the Gregorian calendar), the plan was successfully fulfilled.

The armed forces heading to the Winter Palace. October 1917.

The armed forces heading to the Winter Palace. October 1917.

“Had I not been in Petrograd in 1917, the October Revolution would have still taken place, provided there was Lenin and his leadership. But, if neither I, nor Lenin, had been in Petrograd at the time, the October Revolution would have never happened,” Trotsky later recalled.

Lenin arrived at the Bolsheviks’ headquarters in the Smolny Palace, when everything had already been decided. On the evening of October 25, right after the Winter Palace was taken control of and the provisional government was dismissed, the congress of Soviets - a gathering, where the most important issues of the creation of a new state were resolved - kicked off its work. Lenin suggested that Trotsky head the new executive body - the Council of People’s Commissars, but the latter refused, conceding the leadership to Lenin, while he himself took the post of International Relations Commissar.

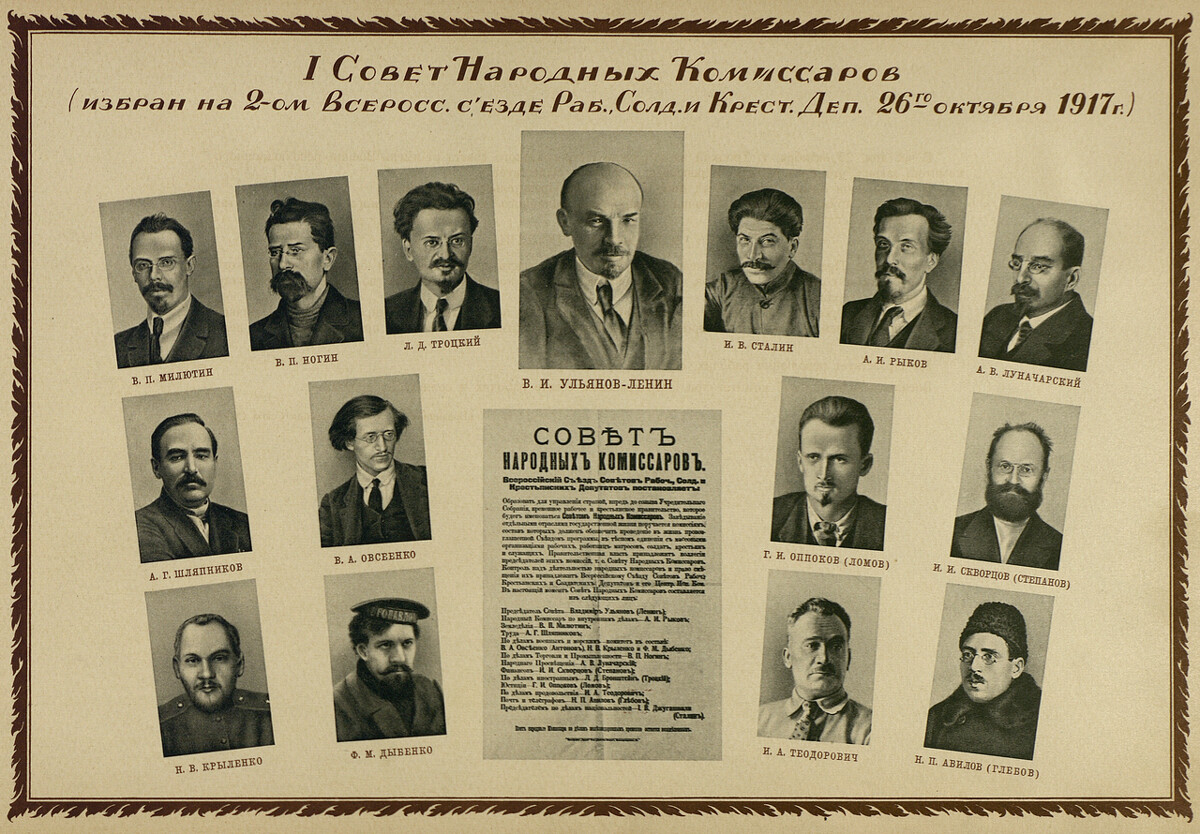

The first Council of People’s Commissars.

The first Council of People’s Commissars.

Trotsky’s demise

In his role as the first foreign minister of the new Russia, Trotsky was to make sure the czarist government’s secret agreements were published (the ministry’s old staff sabotaged it), which he eventually did. Yet, he failed to get the capitalist states to come up with the terms of peace in World War I that would benefit Russia. Nor did he manage to make them recognize the new Russian state (much like his successors, though). Trotsky also couldn’t agree with the conditions of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which had been concluded with Germany on Lenin’s order, making it possible for Russia to withdraw from the war. Trotsky left the post of the Foreign Commissar, being appointed Military and Navy Commissar. Under his leadership, the then disorganized Red Army turned into an effective military machine and changed the course of the Civil War.

Trotsky’s methods were pretty inhumane: when one of the regiments left its positions, not only its commander was executed, but also every tenth soldier.

“One can’t build an army without repressions. There is no way one can send people to fight, if there is no capital punishment in the command’s arsenal,” Trotsky wrote later. His associates were ready to admit that at the time of war and instability, Trotsky’s strategy in terms of army management was justified, but, in state affairs, his radical stance started to scare away even his recent allies.

Leon Trotsky making a speech in front of Red Army soldiers.

Leon Trotsky making a speech in front of Red Army soldiers.

Trotsky’s position was made worse by Lenin’s disease - his opinion was indisputable and he held him in high regard, but it was clear that the head of the party was passing away. In the party ranks, a tough competition for power between Stalin and Trotsky shortly followed. As the Party’s general secretary, Stalin managed to appoint the people he needed to the key roles in the government, thereby building a “coalition” around him that would support all his decisions, while Trotsky’s associates were all dismissed from their jobs. Trotsky lost in this tug of war, being soon found at fault for all his past mistakes, publicly discredited and accused of violating the Party’s policies. In 1927, Lenin’s closest associate and leader of the October Revolution was expelled from the Party and, two years later, in 1929, he was sent into exile.

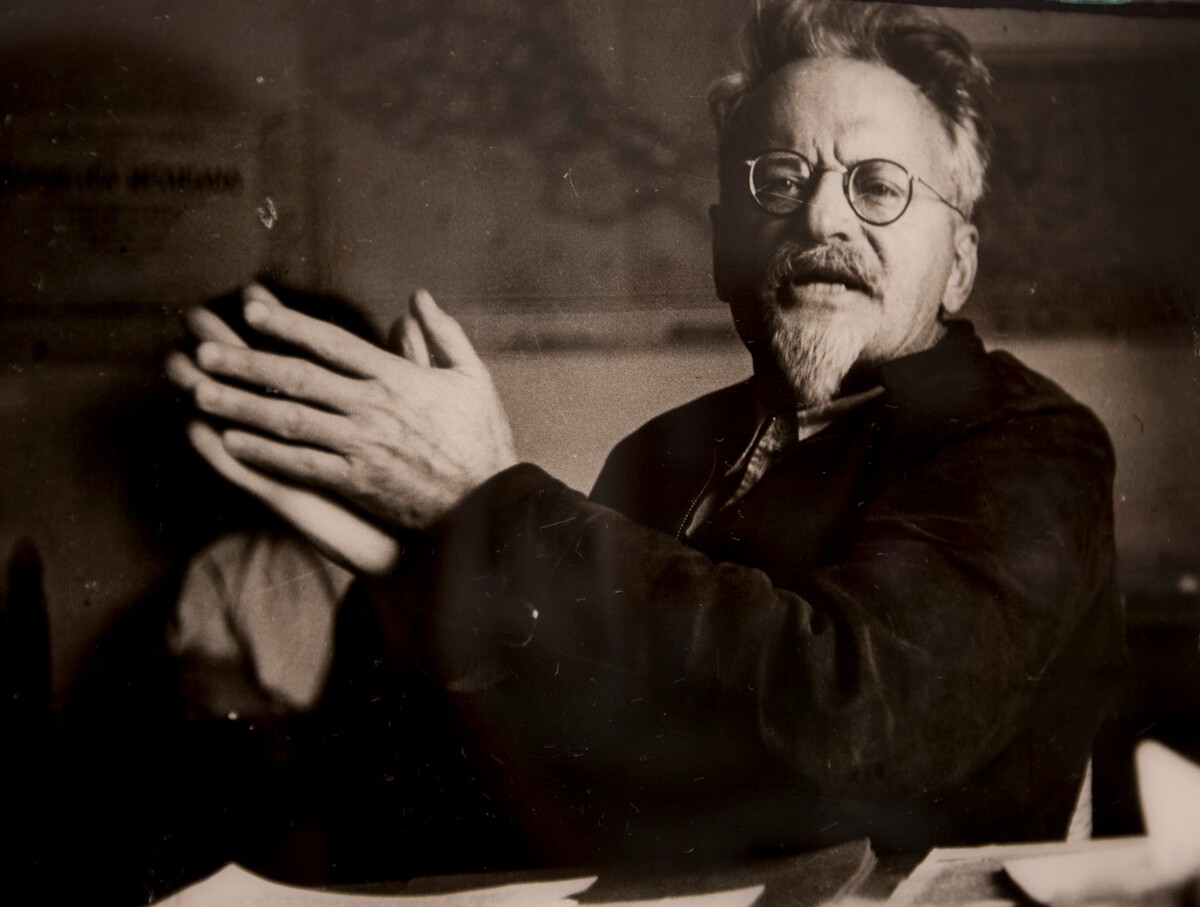

Reproduction of a portrait of Leon Trosky during a speech in his study room, in Mexico City, Mexico.

Reproduction of a portrait of Leon Trosky during a speech in his study room, in Mexico City, Mexico.

Stalin strove to make all of Trotsky’s revolutionary successes be forgotten, with the former commissar becoming a “people’s enemy” and the word ‘Trotskyist’ developing into a dangerous label. If charged with ‘Trotskyism’, one could be put into jail or even shot. In 1940, Trotsky, who was living in Mexico at the time, was traced and killed on Stalin’s order with an ice ax by a Soviet intelligence agent.