Possessed: How Russia’s North copes with a strange mass hysteria

A small, withered old woman named Stepanida Filatovna Vikhareva from the village of Grishata, on the border of the Perm Territory and Udmurtia, casually talks about her children and the weather. Suddenly, the talk is interrupted by ‘ikotka’: the old woman’s voice grows louder than usual; it’s as if the voice comes not from her throat, but from somewhere lower, from her chest. It’s her “other voice” interrupting her, as we might be interrupted by another person: sometimes it’s cursing, sometimes it wails or even argues with the host.

After this intrusion of ‘ikotka’, the woman is silent for a while; if she speaks, it comes out quiet and heavy. It seems like this fit takes a lot of strength away – her facial gestures and eye expression change. She has to recover after this fit.

Stepanida claims ‘ikotka’ has lived with her since she was 17, almost her entire life. She tells her what to do and what she shouldn’t do. “First, she wasn’t letting me take any medicine. Now, one of them overtook [appeared stronger than ‘ikota’],” she says. There were moments when her ‘ikotka’ screamed “day and night”, not letting her sleep. And often, it overcame her during prayers – interrupted prayer, sighed, spoke in interjections. Because of this, Stepanida Filatovna tied her head during prayers with a braided belt – it helped a bit and, due to this, some villagers believed that ‘ikotka’ lives in her head.

This case of possession by the so-called ‘ikota’ or ‘poshibka’ – one of many, described by ethnographers in the Russian North, in the Urals and Siberia. ‘Ikotka’ derives from the word ‘ikat’, which means to “shout out” or “to call”. A person suffering from ‘ikota’ feels pain in different parts of their body; they start behaving like someone is controlling them – imposes different eating preferences, habits and behavior, forcing them to swear or drink alcohol. Sometimes, this is accompanied by hiccups, sporadic shouting of sounds, persistent yawning or throat spasms that change the person’s voice beyond recognition.

The stories and accounts of a state of illness that was allegedly caused by ‘ikota’ – a creature possessing a person – began to be recorded by doctors from the end of the 19th century, when the epidemics of this strange illness flared up one after another in the country: suddenly, whole villages were suffering from it.

“Before, ‘ikota’ was much more widespread than now. Epidemics sprung up in different regions of Russia,” Olga Khristoforova, an anthropologist and a folklorist, a professor at Russian State University for the Humanities and a researcher at RANEPA (Russian Presidential Academy of National Economy and Public Administration), who studied this phenomenon for a long time, says. “At the end of the 19th century, two large epidemics happened in the Smolensk and Novgorod provinces. The last recorded epidemic in Moscow Region happened in Podolsk in 1926. One of the last in the 20th century occurred in 1970 in the Pinezhsk district of Arkhangelsk Region. Party workers were sent there, who were reading lectures that there was no religion and no demon possession, either. At the same time, doctors and scientists studied the phenomenon.”

However, in Russian folk culture, ‘ikotka’ has been mentioned for much longer, starting from the 16th century. People who suffered from it were convinced that they had fallen victim to sorcery.

How the ‘infection’ occurs

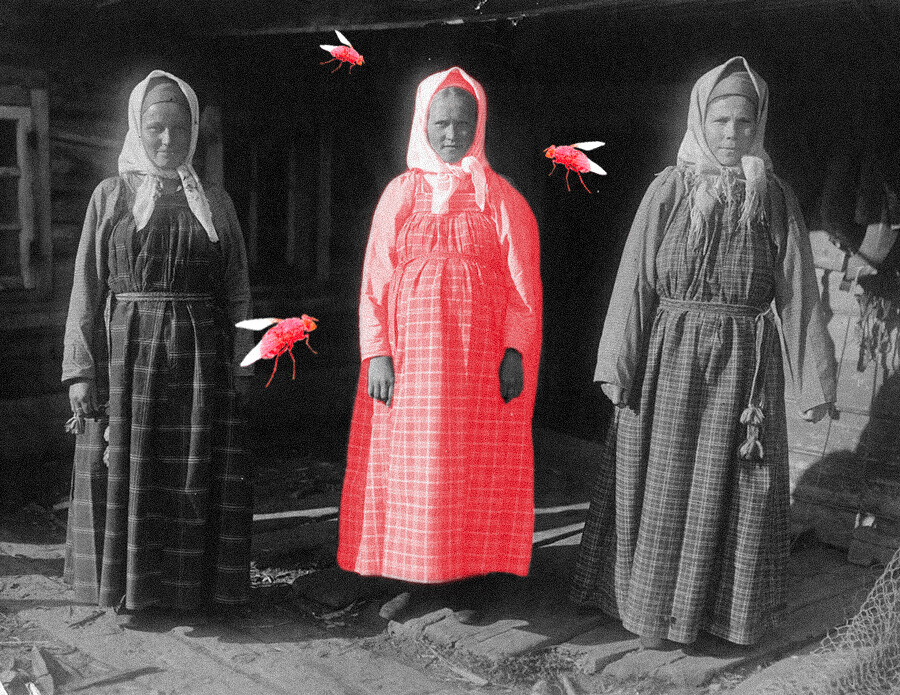

Stepanida Filatovna remembers the exact moment she got infected. She refused to try ‘braga’ (an alcoholic beverage) that she offered to a man named Agey, who came to her relatives for a visit. To drink in front of adults, especially for a young girl in front of a man, with common utensils, was a violation of social and religious norms. An insulted Agey said, “She’ll remember me.” After that, she saw a dung fly at a pond – and this moment forward, she started having “disease attacks”.

‘Ikota’s possession in the shape of a fly – seen or accidentally swallowed – is a popular motif in the stories about how ‘ikota’ “inhabits” people. But, in reality, it could be anything a sorcerer put a curse on, Khristoforova says. People believe that a sorcerer sometimes puts ‘ikota’ into people unseen, without any visible contact.

“This could be a fly over which a sorcerer read a spell and planted ‘ikota’ into it. Or it could be an enchanted speck that was put in your kvass and you drank it. Or a mosquito that flew into one’s mouth, nose or eye – into any of the bodily holes – and now will ‘grow’ inside of a person,” she explains.

A lot of time can pass until ‘ikota’ will ripen and manifest – according to what ‘ikota’-suffering women say, it could let itself be known after decades. Allegedly, over this time, the ‘ikota’ inside of a human changes shape and appearance, depending on different factors. “The ‘ikotka’ of one of the women said this about itself: ‘I went in as a fly, then I was growing, I grew fur and became the size of a cat and now I’m human and my name is Anna Andreevna’,” Khristoforova says.

‘Ikota’ always speaks “inversely”

It’s believed that ‘ikota’ “moves” inside of a human and “gnaws” at their internal organs, feeds on them, slowly incorporating a human body into itself; from this, it grows and changes its biological type. For example, turning from a fly into a mouse or a little human. The more time it spends inside of a human, the more pronounced physicality it has. It even starts talking at the end to some ‘ikota’-suffering women, like it was with Stepanida Filatovna. According to them, they were infected with ‘ikota’ when they were young, but it only started talking when they grew old.

“The talking of ‘ikota’ is the most vivid symptom of it. A throat spasm occurs and a person starts talking ‘inversely’: usually we talk, exhaling the air inside, but when ‘ikota’ talks inside of a human, it inhales the air. Psychiatrists call it a motor-speech paroxysmal attack,” Olga Khristoforova clarifies.

In the cultural context, people with a talking ‘ikota’ are often attributed to clairvoyant abilities and the ability to predict the future. Others come to them with questions about missing people, stolen or lost items, inquiring if they could buy a cow, if their husband will return and so on. ‘Ikota’s answer is then taken as a prophecy. Usually, this prophecy is supposed to be paid for.

In one of the Old Believers’ villages of Verkhokamye, Praskovia Maximovna gained such fame. The woman lived on the outskirts and all neighboring villages came to her for prophecies. She was paid for her divination with food. To another woman, they went only with tobacco as payment – her ‘ikota’ had a male voice, it called itself Fyodor and demanded only tobacco for its prophecies.

But, not everyone has a speaking ‘ikota’ and that partially explains why the beliefs about some creature that possesses a human – ‘ikota’ – are so widespread. “Many people believe that their ‘ikota’ is mute. A mute ‘ikota’ just ‘moves’ around the body and causes pain. That’s why, theoretically, anyone can decide they have an ‘ikota’ if they have something aching,” Khristoforova says.

Why women are affected more often

Russian Priestless Old Believers, who live in the Perm Territory, perceive ‘ikota’ in the context of Christianity. Being possessed with ‘ikota’ they link with demons – the same demons that Jesus, according to the Gospel, exorcized from a demoniac into the Lake of Gennesaret. “And the unclean spirits came out and entered the swine; and the herd, numbering about two thousand, rushed down the steep bank into the sea and were drowned in the sea”.

However, the beliefs of the Komi people, who live near the Old Believers in the same Perm Territory, about a creature possessing humans, have no Christian undertone. The cultures of many other peoples from the Finno-Ugric group don’t have it either. Which, according to anthropologists, means that the belief in ‘ikota’ as a supernatural creature existed among the Finno-Ugric peoples before East Slavs arrived to these lands. In this case, ‘ikota’ is not always considered an evil spirit; some victims of ‘ikota’ coexist and interact with it peacefully.

Footage from the TV series "Territory"

Footage from the TV series "Territory"

According to these ancient beliefs, a sorcerer is also responsible for exorcizing ‘ikota’ from a human. “According to the stories of people, when a sorcerer is exorcizing ‘ikota’, it comes out in the shape of an amorphous lump, similar to a tea fungus. It could be exorcized in different ways. For example, a spell can be put on a shot of vodka in a banya, a person then drinks it and becomes very sick. If the victim is a woman, she begins to “give birth” to ‘ikota’ as if to a child. This motif is very frequent in the legends about ‘ikota’. It explains why women suffer from ‘ikota’ more often than men. It’s rarely planted into men, because this “demon” wants to come out, it wants to “be born”, it doesn’t want to die with the host,” Khristoforova says.

Stepanida Filatovna from Grishata “gave birth” to her ‘ikota’. When asked how big it was, she said it was about 20-30 centimeters. Before that, she thought she was pregnant. “After it was born, I took a rag, wrapped it into the rag and threw it under the stairs. The next morning, I woke up and there was nothing there. It went back into me again,” she said. When asked how it managed to get back inside, the woman couldn’t answer. But, she could describe what she saw: ‘ikota’ was round, looking like a cow’s lung.

In the end, she couldn’t manage to get rid of ‘ikota’. It’s believed there are no more strong sorcerers left who can perform the exorcism. So, people are used to thinking that if ‘ikota’ possesses them, it will continue living in them for the rest of their lives. However, as researchers think, in reality, it’s just disadvantageous to get rid of ‘ikota’ for those who believe in it.

The reasons to be possessed

‘Ikota’ is not just a psychic, but also a complex sociocultural phenomenon. First of all, it’s a way to wrap your negative feelings (enmity, envy, hatred, grievance) into a socially acceptable shell.

“Sometimes, it’s hard to express one’s attitude towards people. The belief in sorcerers is a method of making your personal complaints towards someone legitimate. You can’t simply say, ‘Ivan Ivanovich is a bad man, he doesn’t belong here.’ But, to accuse him with the ‘ikota’ voice, claim he’s a sorcerer, a bad man and not take any responsibility for this is okay. It’s not you speaking, after all, it’s a demon inside you,” Khristoforova explains.

The following fact supports this: there were never any persecutions of ‘ikota’-suffering women (no matter how horrible their fits may have been) in Russia. They were considered victims of sorcery and acted as a prosecutor – exposing those who cursed them with ‘ikota’. Those people were then prosecuted.

But ‘ikota’ is not always meant to pursue social benefits. “Elderly people write off their health problems on ‘ikota’. First, because they believe in God and demons and, second, because they have lived a hard life, they worked a lot and their bodies have become worn out early. People don’t explain their illnesses with natural reasons, but, with ‘ikota’ instead, because it’s easier to accept. Especially where there are few doctors or when healthcare is inaccessible,” Khristoforova says.

Footage from the TV series "Territory"

Footage from the TV series "Territory"

Science easily finds explanations for ‘ikota’ epidemics, as well. At the end of the 19th century, it was attributed to mass hysteria. Such a condition – when people start to copy abnormal behavior of one another – has been recorded for many centuries all over the world. The outbreaks of a dance mania appeared in Europe during 14th-17th centuries: hundreds of citizens danced, unable to stop moving; some of them died of heart attacks or from exhaustion. Or, for example, the laughter epidemic in Tanzania in 1962: it started with three giggling schoolgirls, but, over a year, spread to more than a 1,000 schoolkids who laughed and cried at the same time, unable to stop. This case has made it into textbooks as a classic example of mass hysteria.

“The cultural tradition defines how people behave. Somewhere, it will be laughter, in other places – lying around on the floor. That’s why science calls it a culture-bound syndrome – the reproduction of patterns usual for a specific culture. In the case of ‘ikota’, it’s the pattern of the belief in possession. Depending on the local environment it would be called differently – ‘ikota’, ‘sheva’ or ‘poshibka’ – but it will always be about a possession by some kind of creature,” Khristoforova says.

Psychiatrists have named different conditions for the emergence of ‘ikota’ epidemics. In the 1970s, the condition was recorded both when a person was absolutely healthy (when a superstitious person, seeing someone else having such attacks, themselves begins to experience a similar thing) and in a disease state of a psychogenic or non-psychogenic nature. ‘Ikota’ almost always appears after some stressful experience.

For a long time, scientists argued that possession patterns help weak and dependent members of society compensate for their unenviable social situation. The possession was even dubbed “the weapon of the weak”. For example, it was noticed that unmarried women are often subject to possession, who feared not meeting social expectations. The sickness and sorcery granted them certain benefits – removal from work, care and attention and even power (clairvoyants were always respected).

In the 21st century, ‘ikota’ as a phenomenon remains in some separate village regions where the tradition was strong. Perm psychiatrists continue to record this condition across the entire Perm Territory, but it’s not called an epidemic anymore. It’s more of a special case. In Arkhangelsk Region, as Khristoforova says, it virtually disappeared. “Generations change, people leave to the cities and not many young people are the recipients of these culture models. People have become more literate, medicine has gotten better.”